Reasonableness Is Unreasonable: A New Jurisprudence of New

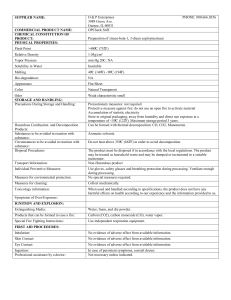

advertisement