THE ABSURD AND THE COMIC A Thesis by PHILIP PARK

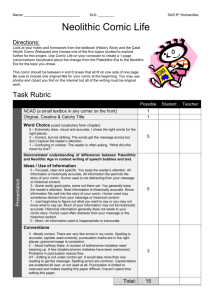

advertisement