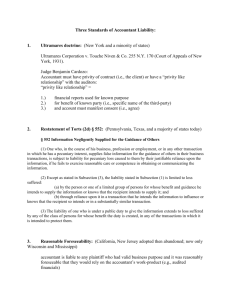

liability of lawyers and accountants to non

advertisement