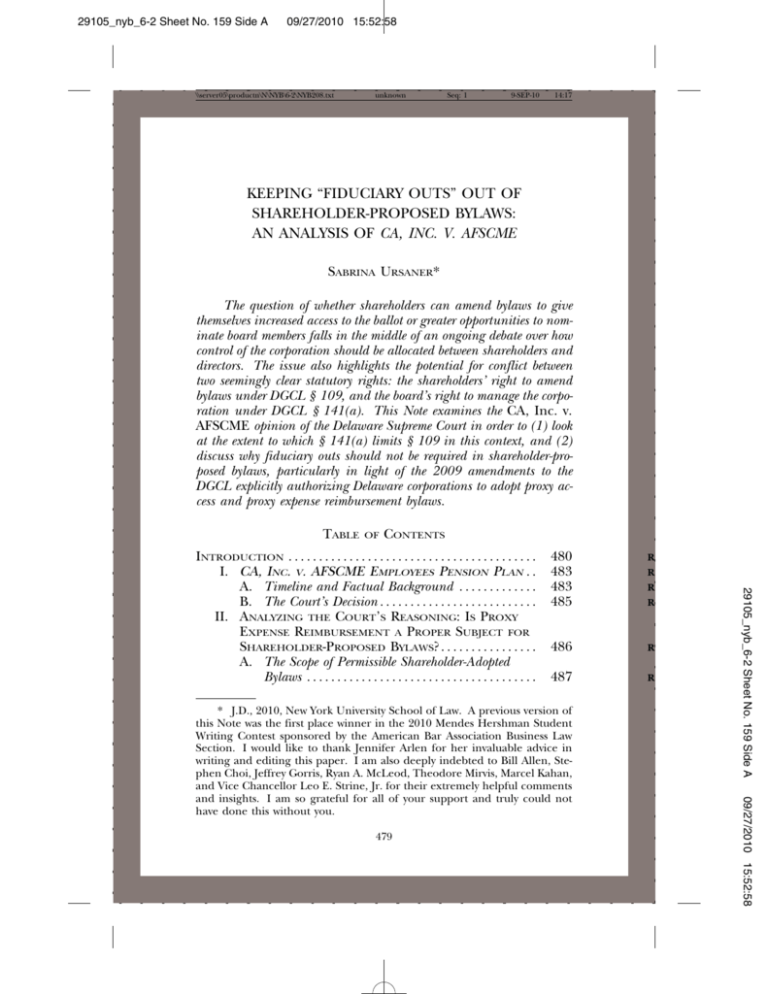

out of shareholder-proposed bylaws

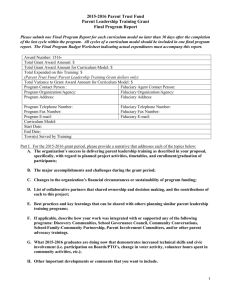

advertisement