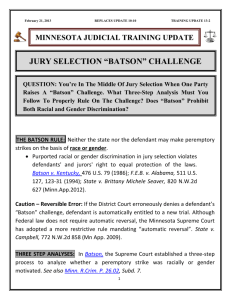

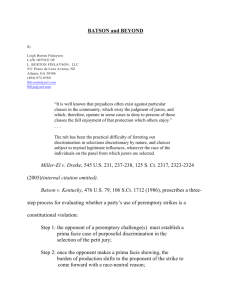

ARTICLE MILLER-EL V. DRETKE, RICE V. COLLINS, &

advertisement