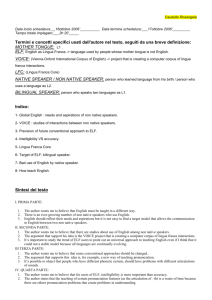

the case for a description of English as a lingua

advertisement