Intimate Apparel - The Pasadena Playhouse

advertisement

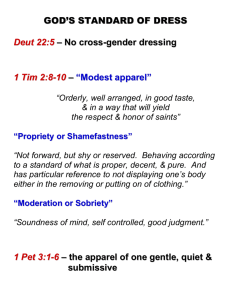

Intimate Apparel By Lynn Nottage Directed by Sheldon Epps Education Guide Table of Contents Setting, Synopsis, and Cast of Characters............................................................. 2 Intimate Apparel Production History.................................................................. 5 Playwright Lynn Nottage, on Writing Intimate Apparel............................................6 Creative and Design Team................................................................................7 The African-American Experience at the Turn of the 20th Century...............................9 Working African-American Women in Northern Cities..........................................10 Jewish Americans in New York City .................................................................12 Working on the Panama Canal ........................................................................13 Monetary Values in 1905 and Today .................................................................15 Glossary ...................................................................................................16 Supporting Questions and Exercises .................................................................17 Prepared by Dramaturg Elyse A. Griffin for the Pasadena Playhouse October 2012 2 Setting, Synopsis, and Cast of Characters Setting: Manhattan, 1905. Synopsis: Esther, a middle-aged, black seamstress, has learned to make ends meet by teaching herself to sew beautiful and delicate lingerie for her uptown and downtown clientele. After nearly two decades of loneliness and watching the younger and prettier girls come and go in the boarding house she rents from, Esther finds solace and possible romance in letters from George, a handsome, young Caribbean man working on the Panama Canal. Re-energized by his affectionate words, but hindered by illiteracy, Esther confides in two of her patrons, Mrs. Van Buren, a rich white socialite, and Mayme, a prostitute, to pen her letters back to George. Meanwhile, Esther’s heart also seems to lie with Mr. Marks, the Hasidic shopkeeper who relishes in sharing his exquisite finds of satins and silks and has also grown increasingly fond of Esther. Characters in order of Appearance: Vanessa Williams (“Soul Food,” “Lincoln Heights,” “Melrose Place”) – Esther Angel Reda (Dangerous Beauty, Follies, Wicked)— Mrs. Van Buren Dawnn Lewis (Dreamgirls, Sister Act-The Musical, “A Different World”)—Mrs. Dickson Adam J. Smith (“As the World Turns,” “Bounty Wars,”) – Mr. Marks 3 Kristy Johnson (Jitney, The Good Negro)—Mayme David St. Louis (“Third Watch,” Parade, Rent, Ruined) – George Questions in Context: 1) Who was your favorite actor? Write a thank you letter to him or her. Let them know why you enjoyed the performance and why it was nice to be able to come to this specific performance. 2) The actors in this show also act on television and in films. What do you think are the different demands of acting on stage versus acting for the camera? Do you think there is a difference? 4 Intimate Apparel Production History Intimate Apparel was first commissioned and produced by South Coast Repertory and Center Stage in Costa Mesa California, opening on April 18, 2003. It was directed by Kate Whoriskey; the set design was by Walt Spangler; the costume design was by Catherine Zuber; lighting design by Scott Zielinski; sound design by Lindsay Jones; original music by Reginald Robinson; arranger and piano coach William Foster McDaniel; dramaturg Jerry Patch; associate production dramaturg Rhonda Robbins; production manager Tom Aberger; production stage manager Randall K. Lum. Cast: Esther....................................Shané Williams Mrs. Dickson...........................Brenda Pressley Mrs. Van Buren.............................Sue Cremin Mr. Marks.............................Steven Goldstein Mayme......................................Erica Gimpel George.....................................Kevin Jackson Shané Williams and Erica Gimpel in South Coast Repertory’s original production of Intimate Apparel. Intimate Apparel was originally produced in New York City by the Roundabout Theatre Company, opening on April 8, 2004. It was directed by Daniel Sullivan; the set design was by Derek McClane; costume design by Catherine Zuber; lighting design by Allan Lee Hughes; original music by Harold Wheeler; sound design by Marc Gwinn; production stage manager Jay Adler; stage manager Amy Patricia Stern. Cast: Esther...........................................Viola Davis Mrs. Dickson...............................Lynda Gravatt Mrs. Van Buren.............................Arija Bareikis Mr. Marks......................................Corey Stoll Mayme........................................Lauren Velez George....................................Russell Hornsby Corey Stoll and Viola Davis in the Broadway production. 5 Playwright Lynn Nottage, on writing Intimate Apparel Lynn Nottage is the author of Intimate Apparel, which was produced in New York at Roundabout Theatre Company after its worldpremiere production at Center Stage and South Coast Repertory. The play received numerous awards, including the 2004 New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award for Best Play. In an article for the Los Angeles Times, Lynn Nottage talked about how her own family history the played a part in the inspiration and creation of Intimate Apparel. Excerpted from “Lives Rescued from Silence” by Lynn Nottage, Los Angeles Times, April 13, 2003: A couple of years ago, I began researching a play about a lonely African American woman searching for intimacy in New York City during the early 1900s. As a native New Yorker, I'd become intrigued with the social lives of African American city dwellers in the early 20th century. I knew shockingly little of the city's history and found the prospect of venturing into new territory a welcome diversion. I spent hours in the New York Public Library, obsessively exploring the dimly lighted honky-tonks and brothels of the notorious Negro tenderloin district and the cramped, overpopulated residences of San Juan Hill. I could almost hear the syncopated ragtime piano filling the saloons and dance halls in the Negro districts. These African American neighborhoods promised a wealth of untapped stories. [...] Sitting in the main hall of the New York Public Library, I had an epiphany: If my family hadn't preserved our stories, and history certainly had not, then who would? It led me to revisit the shoe box of neglected photographs beside my writing desk. It was placed there for a reason. The undisturbed image of my great-grandmother was still nestled on the top of the pile of forgotten relations; her mute image begged for recognition. In a rare candid moment, my grandmother once shared that her mother was a Barbadian seamstress who created intimate apparel for women at the turn of the century. She arrived in New York alone, and soon after began corresponding with a handsome Barbadian laborer consigned to the Panama Canal. The long-distance exchange led to a short-lived marriage a year later. [...] In hunting for a play, I established an intimate dialogue with my great-grandparents. I was finally able to release them from the shoe box and allow their memory to breathe. I never expected that my family would be the wonderful byproduct of months of research to craft a play. Questions in context: Part of the inspiration to write this play came from playwrights Lynn Nottage’s own life. What else do you think could inspire someone to write? Think about your favorite stories, movies, or television shows. Do a little research and see if you can find out where the creator’s original inspiration came from. Was it something from his or her own life? A loved one’s? Another piece of writing or work of art? 6 The Creative and Design Team of Intimate Apparel Sheldon Epps – Director Theatre directors are responsible for creating a vision of a playwright’s script; they lead the cast and crew in the process from the page to the stage. They direct the actors in the rehearsal process and oversee the other creative elements of the play. Hethyr Verhoef – Stage Manager The stage manager of a production is involved with every part of the production process. He or she schedules and runs rehearsals, coordinates the stage crew, calls cues and entrances during a performance, and oversees the whole show each time the play is performed. John Iacovelli – Scenic Designer A scenic designer designs the overall look of the set of a play to reflect the original script and the director’s vision for the specific production. Brian Gale – Lighting Designer Collaborates with the set designer and director to create the “look” of the play using the lighting. Steven Cahill – Sound Designer Designs the “soundscape” of the play, including sound effects and music required in the script. Leah Piehl – Costume Designer Stage Manager Hethyr Verhoef on the rail backstage. Design the clothes and accessories of each character in the play to faithfully reflect the script and the director’s vision of the characters. Questions in Context: 1) Which creative or design job would you like to do? 2) Write a letter to your favorite design team member. Did you like the lighting design the best? The set? Let that person know what you liked, ask them how they did it, and what you would have done. 7 3) Advertising is also an important part of a play production. Take a look at the image below, and the image used in the advertising for Intimate Apparel. What would you think this play is going to be about just based on this image? How would you design the advertising for this play? What do you think needs to be communicated through the advertising of a play, so that the audience will want to come see it? 8 The African-American Experience at the Turn of the 20th Century The following is excerpted from the transcript of an interview with historian Margaret Washington for the PBS documentary series 1900. The Feeling of Optimism in America “An Alley in the Lower West Side of New York—Within two Blocks of Fifth Avenue” “1900 appeared to be a time of optimism, a time of American sense of assertion, a time of America's sense of its own power, of its own people, specifically white people. It was also a time of transition because America was still in the Victorian age, at the same time America was shedding its Victorianism. It's almost like America was sort of shaking itself and emerging into something new and coming into its own. It was no longer looking toward a kind of morality and a kind of sense of what was right, looking toward Britain, which is what they had done in terms of their social system, in terms of their sense of what was proper and what was correct. America was maturing socially, politically and economically in 1900. There was a darker side to this sense of optimism in America in 1900. America was becoming a society of immigrants, people who were different from the previous immigrants. Many of them were from southern Europe. That meant that they were darker. Then of course there was the African American population. So the individuals who were responsible for the labor force were part of this horde of inferior peoples in American society. So when we think about the optimism, we're not necessarily including these people who are part of that other half. For them it's not so much a period of optimism. Although even for the people who are not included in this sense of optimism, they themselves had a sense of aspiration and a sense of hope.” http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/1900/filmmore/reference/interview/index.html 9 Working African-American Women in Northern Cities In Act 1 Scene 2 of Intimate Apparel, Esther says to Mayme that she has been saving her money since she came North to work in New York. Esther’s journey North was common of many African American women at the turn of the century. From Women and the American Experience by Nancy Woloch If the black woman worker had one thing in common with the white wageearning woman, it was the growing likelihood that she lived in or moved to a city. Most black migrants moved to southern cities. But even before the massive black urban migrations of the World War I era, indeed, before the nineteenth century was out, the lure of jobs drew southern black women to northern cities in greater numbers than black men. Whereas among immigrant groups, who were settling in northern cities, men were always in a majority, women predominated among black urban migrants. In New York in 1890, for instance, there were 81 black men for every 100 black women. ...Black women dominated the ranks of early urban migrants because they were always able to get jobs, as men could not, in the growing market for domestics—as cooks, laundresses, scrubwomen, and maids. From The African-American Migration Experience: The Northern Migration The rampant discrimination against black men in the Northern labor markets made it unlikely that a family could be supported on one salary. The domestic work open to AfricanAmerican women was often steady, unlike the seasonal nature of many of the laboring jobs available to men. One attractive feature of domestic work in the homes of others, or of "taking in" washing or sewing at one's own home, was that such an arrangement allowed for the care of children at the workplace. Black women were often very influential within the household. 10 The story of Chloe Spear provides an interesting account of one African-American "Wonder Woman." Born in Africa and enslaved in Boston until the end of the eighteenth century, Chloe married Cesar Spear, also a slave. After the family was freed, the Spears operated a boardinghouse in the city. In addition, Chloe did domestic work for a prominent family. While she was at work, Cesar saw to the cooking and other duties associated with the boardinghouse but when she returned in the evening he turned the operation over to her while he was "taking his rest." After working all day, Chloe cooked dinner for her family and for the boarders and cleaned the house. In order to make extra money, she took in washing, which she did at night, setting up lines in her room for drying the clothes. She slept a few hours while the clothes dried, then ironed them and prepared breakfast for the household before going off to work for the day. Although one might easily conclude that women like Chloe were cruelly exploited by their husbands, the reality was not quite so simple. Chloe did not routinely hand over her wages to her husband, as did most white working women of the period. She controlled her own money, as is usual among African women. At one point she decided to purchase a house despite the fact that the law prohibited married women from buying property in their own name. Chloe was forced to ask her husband to make the purchase for her. Told that it cost $700, Cesar determined that he could not afford it. "I got money," Chloe announced, and Cesar agreed to sign for the house. Studies of the black family have long noted the increased independence and authority women exercised within the household because of their crucial role in the family economy. Chloe is an excellent example of the way African-American women asserted that role. Images from album: “Types of American Negroes,” compiled and prepared by W.E.B. Du Bois, c. 1900. 11 Jewish Americans in New York City From “The American Jewish Experience in the 20th Century: Assimilation and Antisemitism” by Jonathan D. Sarna and Jonathan Golden The twentieth century witnessed the emergence of American Jewry on the world Jewish scene. As the century opened, the United States, with about one million Jews, was the third largest Jewish population center in the world, following Russia and Austria-Hungary. About half of the country's Jews lived in New York City alone, making it the world's most populous Jewish community by far, more than twice as large as its nearest rival, Warsaw, Poland. By contrast, just half a century earlier, the United States had been home to barely 50,000 Jews and New York's Praying on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement, early 1900s. Jewish population had stood at about 16,000. Immigration provided the principal fuel behind this extraordinary American Jewish population boom. In 1900, more than 40 percent of America's Jews were newcomers, with ten years or less in the country, and the largest immigration wave still lay ahead. Between 1900 and 1924, another 1.75 million Jews would immigrate to America's shores, the bulk from Eastern Europe. Where before 1900, American Jews never amounted even to 1 percent of America's total population, by 1930 Jews formed about 3½ percent. There were more Jews in America by then than there were Episcopalians or Presbyterians. This massive population transfer radically transformed the character of the American Jewish community. It reshaped its composition and geographical distribution, resulting in a heavy concentration of Jews in East Coast cities, including some (like Boston) where Jews had never lived in great numbers before. It also realigned American Jewry's politics and priorities, injecting new elements of tradition, nationalism, and socialism into Jewish communal life, and seasoning its culture with liberal dashes of East European Jewish folkways. Although the American Jewish community retained significant elements from its German and Sephardic pasts (Sephardic Jews having Jewish neighborhood in New York city, early 1900s. originated in Spain and Portugal), the traditions of East European Jews and their descendants dominated the community. With their numbers and through their achievements, they raised its status both nationally and internationally. http://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/tserve/twenty/tkeyinfo/jewishexp.htm 12 Working on the Panama Canal The following is excerpted from the article, “The Workers” on the companion website to the American Experience television documentary series Panama Canal. "You here who are doing your work well in bringing to completion this great enterprise are standing exactly as a soldier of the few great wars of the world's history," Teddy Roosevelt announced to workers during his trip to Panama in 1906. "This is one of the great works of the world." In December of that year, two years into the project, there were already more than 24,000 men working on the Panama Canal. Within five years, the number had swelled to 45,000. These workers were not all from the United States, but from Panama, the West Indies, Europe, and Asia. The base of the workforce, however, once again came from the West Indies. After experiencing Teddy Roosevelt with Canal workers the empty promises of the French in the 1880s, most Jamaican workers were unwilling to try their luck on the American canal project, and so in 1905 recruiters turned their attention to the island of Barbados. West Indian labor was cheaper than American or European labor, and a West Indian worker was eager to believe a rags-to-riches tale spun by a recruiter. The "Colón Man" was reborn as representatives from Panama boasted of a rewarding work contract, including free passage to Panama and a repatriation option after 500 working days. By the end of the year, 20 percent of the 17,000 canal workers were Barbadian. West Indians recruited with promises of wealth and success confronted a very different reality upon arrival at the Isthmus. The dense and untamed jungle that covered the 50 miles between coasts was filled with deadly snakes. The venom of the coral snake attacked the nervous system, and a bite from the tenfoot mapana snake caused internal bleeding and organ 13 degeneration. The rainy season, which lasted from May to November, kept workers perpetually wet and coated in mud. [...] The living conditions exacerbated the poor hygiene in the area, and newcomers quickly learned about the serious threat of disease on what was dubbed "Fever Coast." Smallpox, pneumonia, typhoid, dysentery, hookworm, cutaneous infections, and even the bubonic plague infected workers throughout the American excavation period, but yellow fever was the most treacherous ailment, both physically and mentally. [...] As work on the canal entered its second year, the death toll for laborers was four percent and 22,000 were hospitalized. Every evening, a train traveled to Mount Hope Cemetery by the city of Colón, its cars brimming with coffins, forcing the men to confront the great odds against their survival. http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/general-article/panama-workers/ 14 Monetary Values in 1905 and Today From MeasuringWorth.com: In 2011*, the relative value of $1.00 from 1905 ranges from $20.40 to $524.00. A simple Purchasing Power Calculator would say the relative value is $26.40. This answer is obtained by multiplying $1 by the percentage increase in the CPI from 1905 to 2011. If you want to compare the value of a $1.00 Income or Wealth, in 1905 there are three choices. In 2011 the relative: historic standard of living value of that income or wealth is $26.40 economic status value of that income or wealth is $141.00 economic power value of that income or wealth is $524.00 The CPI (Consumer Price Index) is most often used to make comparisons partly because it is the series with which people are most familiar. This series tries to compare the cost of things the average household buys such as food, housing, transportation, medical services, etc. For earlier years, it is the most useful series for comparing the cost of consumer goods and services. It can be interpreted as how much money you would need today to buy an item in the year in question if its price had changed the same percentage as the average price change. Examples: In 1968, the average price of a gallon of gasoline in the US was 34 cents. Compared to other things that the average consumer bought that year, this would be comparable to $2.10 using the CPI index for 2009. As to how "affordable" it is to the average person, 34 cents in 1968 would correspond to spending $3.48 out of an average income by using the GDP per capita index. In 1931, an accountant in the US would be earning about $2,250, an amount that would represent a comparative purchasing power of $31,700 in current dollars. However, this salary is almost 45% more than what the average household spent in those days. This would correspond to $168,000 today, a "status" of nearly twice the national average. *We use annual data for our computations, therefore, it is necessary to have an annual observation for both the initial year and the desired year. For the indices based on GDP, it is only after the year is over that GDP can be measured. For price indices, the annual observations are usually the average of monthly observations. It would not be valid to compare a monthly observation in the current year with an annual observation in an earlier year. 15 Glossary Accoutrements: an accessory item of clothing or equipment. Busylickum: (slang) A nosy person, a busybody. Chattel: an item of tangible movable or immovable property except real estate and things (as buildings) connected with real property; a slave, bondman. Duppy: (slang) Duppies are restless spirits of the dead that are believed to haunt the living. Contrary to the good spirit, the duppy is seen as the unnamed, unhappy, and restless dead human who is capable of doing harm. A flamboyant tree. Flamboyant (noun): A species of flowering plant (Delonix regia). It is noted for its fern-like leaves and flamboyant display of flowers. The tree's vivid vermilion/orange/yellow flowers and bright green foliage make it an exceptionally striking sight. Ignorant oil: (slang) alcohol, especially cheap and potent alcohol Monkey chaser: (slang) a West Indian Mulatto: a person of mixed white and black ancestry Suffragettes: Women in Britain, Australia and the United States in the early 20th century who was a member of a group that demanded the right of women to vote and that increased knowledge of the subject with a series of public protests The Tenderloin: The Tenderloin was the premier sex-work district in New York City in the early 1900s. It was vast, reaching from A Suffragette. Gramercy Park and Murray Hill on the east and working-class Hell’s Kitchen on the west, north from Twenty-third Street Between Fifth and Eighth Avenues. Through the second half of the 19th century, the Tenderloin grew from having been an elite, wealthy, white neighborhood to a center of commerce and entertainment. Hotels, theatres, and restaurants brought with them an upsurge of nightlife, which attracted prostitutes to the area. Wealthy residents of the area began moving uptown to escape the changing conditions of the Tenderloin area, and as a result landlords rented to houses of prostitution because they were able to afford higher rent than working-class tenants. It is most likely that the character of Mayme lives and works in the edge of the Tenderloin district between W 36th and to 41st Street, between Eighth and Ninth Avenues, where the majority of black prostitution was relegated. 16 Supporting Questions and Exercises 1. Who was your favorite character? Did you agree with how he or she handled him or herself? Put yourself in their shoes. How would you act in similar situations to the ones they are in? 2. Does the setting of the play matter? How would this play be different if it were set in another country? Another part of the U.S.? Another time era? How would the relationships change? 3. Each character has a dream or a desire, and something that stands in the way of it. What are they? How are they different and similar for each character? 4. In what ways are the characters connected to each other (circumstances, desires, loves, etc.)? 5. Did any of the characters change over the course of the play? In what way? 6. Whose story is this: Esther? Mayme? Another character? Several? 7. How do each character’s actions and words affect the others? 8. Was this a story with a happy ending for anyone? Why or why not? What do you think will happen to these characters after the play’s ending point? 9. If you could rewrite the story, would you? Would you make it happier, sadder, etc.? Would you add other characters? 10. How would you describe this play to a friend? What would be the 3 most important things you think you should mention? 11. What do you think are the themes of this play? 12. What do you think the title Intimate Apparel means? 13. If this play were a kind of fabric, what would it be? 17 References http://www.scribd.com/doc/28787253/Vice-Slang http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/accoutrement http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/british/suffragette http://www.buzzle.com/articles/flamboyant-tree.html, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Delonix_regia http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/chattel http://books.google.com/books?id=4YfsEgHLjboC&pg=PA315&lpg=PA315&dq=busylickum&source=bl&ots=7J TCPai058&sig=IiucBrKMQVcIMCcFVlXcUbhaYE8&hl=en&sa=X&ei=RzeUUJWfN8PXyAH1iYCgCQ&sqi=2&v ed=0CDIQ6AEwAw#v=onepage&q=busylickum&f=false http://www.thefreedictionary.com/worsted http://aalbc.com/authors/harlemslang.htm http://www.go-localjamaica.com/readarticle.php?ArticleID=6446 http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/mulatto Blair, Cynthia M. I Got to Make My Livin’: a study of black women’s sex work. Gilfoyle, Timothy J. City of Eros: New York City, Prostitution, and the Commercialization of Sex 1790-1920. By 18