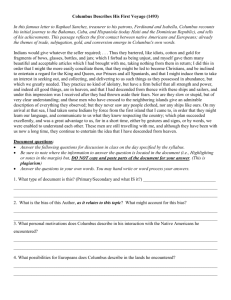

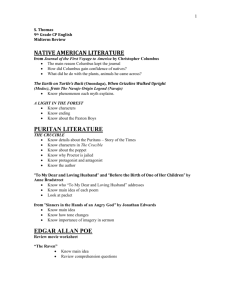

Examining Historical (Mis)Representations of Christopher Columbus

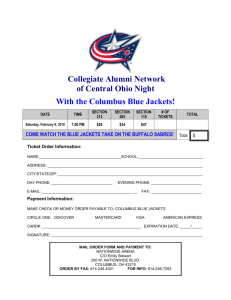

advertisement