The Temple, the Sepulchre, and the Martyrion of the Savior

The Temple, the Sepulchre, and the Martyrion of the Savior

Author(s): Robert Ousterhout

Reviewed work(s):

Source: Gesta, Vol. 29, No. 1 (1990), pp. 44-53

Published by:

The University of Chicago Press

on behalf of the

International Center of Medieval Art

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/767099

.

Accessed: 28/02/2013 18:27

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

The University of Chicago Press and International Center of Medieval Art are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Gesta. http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded on Thu, 28 Feb 2013 18:27:22 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Temple, the Sepulchre, and the Martyrion of the Savior*

ROBERT OUSTERHOUT

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

In memory of Kathleen Shelton

Abstract

This paper examines the ideological relationship of the Holy Sepulchre and the Temple of Jerusalem, as manifest in writings, ceremonies, and architecture.

A possible relationship between the form of the Tomb aedicula at the Holy Sepulchre and early representa- tions of the Ark of the Covenant is explored. Related to this, the origin and significance of the term mar- tyrion in reference to the site of the Holy Sepulchre is discussed. The term was apparently derived from the prophetic language of the Septuagint, and thus meant something different from simply a martyr's shrine.

Finally, some comments are presented on the inter- pretation of the symbolic language of architecture. vW9 wf

With the construction of the church of the Holy

Sepulchre, begun by Constantine the Great in A.D. 326, the city of Jerusalem once again possessed a major reli- gious shrine. The Temple of Jerusalem had been destroyed in A.D. 70 during the Roman sack of the city, and it was never rebuilt. In describing Constantine's building pro- gram, the emperor's biographer, Eusebius, Bishop of

Caesarea, invited a comparison of the two: the Holy

Sepulchre is the "New Jerusalem, facing the far-famed

Jerusalem of old time . . ." and the Tomb of Christ is called the "Holy of Holies," contrasting the new architec- tural creation on the western hill of the city with the ruins of the Jewish Temple to the east of the Tyropoeon Valley, where the Dome of the Rock now stands (Fig. 1).1 In effect, the Holy Sepulchre became the New Temple.

Such an ideological transformation, symbolizing the change from the Old Covenant to the New Covenant, found several forms of expression in the Early Christian centuries. I am not implying that the Holy Sepulchre was constructed as a "copy" of the Temple, and the com- parison of the two buildings can be taken only so far. But for the Christian visitor to Jerusalem, the symbolic content was enriched by the strength of the association. Moreover, because of resonance and richness of allusion at the Holy

Sepulchre, the complex provides us with an instructive example for the study of the iconography of architecture.

That is, if architectural form is to be the bearer of mean- ing, how is a specific or general interpretation attached to a given form? Krautheimer introduced the examination of such questions more than forty years ago in a study that focused on the architectural copies of the Holy Sepulchre.2

01-

..........

AW

FIGURE 1. Jerusalem, aerial view with the Holy Sepulchre in the foreground and the Dome of the Rock on the Temple Mount in the distance (Time Magazine).

However, in an architectural copy there is a repetition of elements that provides something of a formal "hook" to hang our meaning on. The association between these two great Urbilder, the Holy Sepulchre and the Temple, is more complex and more elusive.

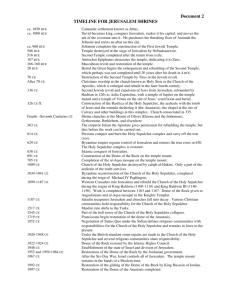

To be sure, the two buildings were lacking in most formal similarities. The Temple had been rectangular in plan, preceded by a broad porch. It faced east onto a court, where its altar was located. The interior was divided

44 GESTA XXIX/1 ? The International Center of Medieval Art 1990

This content downloaded on Thu, 28 Feb 2013 18:27:22 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Chamber

Rinsing

Gate of the

Offerings oFi

Court of the Gentiles

Gate of the

Flame

I I

--

IChamber

I

Lepers

Chamber

Wood court of Women The Beautiful Gate

Gatr echal lmNicanr's

U

Waam rGate

AaI

L

Ls hLKaver ofg

&.V of ao

W s f hn

T ee t scale feet

100

FIGURE 2. Jerusalem, Temple of Herod. Hypothetical plan (after Comay). between the sanctuary and the Holy of Holies, which once contained the Ark of the Covenant (Fig. 2).3 In contrast, the Holy Sepulchre was a complex of buildings with an atrium, a five-aisled basilica, an inner court with the chapel of Calvary in the southeast corner, and the Anas- tasis Rotunda to the west, containing the aedicula of the

Tomb of Christ (Fig.

3).4

Nevertheless, there are a few similarities. For example, the orientation of the two buildings was the same, that is, with the entrance to the east, and, according to the late fourth-century pilgrim Egeria, the dedications were also related. She wrote:

The date when the church on Golgotha (called Marty- rium) was consecrated to God is called Encaenia, and on the same day the holy church of the Anastasis was also consecrated.. . the day of Encaenia was when the

House of God was consecrated, and Solomon stood in prayer before God's altar, as we read in the Books of

Chronicles.5

An association seems to have been made primarily on the basis of function, and the timing and organization of individual celebrations, as well as the ordering of the liturgical calendar, reflected Jewish worship. Wilkinson has suggested that parts of the early liturgical celebration at the Holy Sepulchre were structured following the model of the ceremonies at the Temple.6 The synagogue service may have provided a liturgical intermediary, but many elements would seem to relate directly to the Temple. For example, the timing of the Morning Whole-Offering at the

Temple is paralleled in the Weekday Morning Hymns at the Holy Sepulchre. Both began at cockcrow with the opening of the doors; morning prayers or hymns were begun at daylight. Subsequently, in the Temple service, the High Priest and other priests entered the Temple and prostrated themselves; whereas at the Holy Sepulchre, the

Bishop and clergy entered the Tomb Aedicula for prayers and blessings. Then, in both ceremonies, the officiants emerged from the entrance of the Temple or Tomb to bless the people.

In other celebrations described by Egeria, if the com- parison with Temple service holds, the Tomb of Christ takes the place of the Temple or, perhaps more specifically, the Holy of Holies. The ever-burning lamp in the Tomb may be likened to the menorah in the Temple (or perhaps

45

This content downloaded on Thu, 28 Feb 2013 18:27:22 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

S4

-0, i

5.,

1. Patriarchate

2. Anastasis Rotunda

3. Tomb Aedicula

4. Courtyard

5. Calvary

6. Basilica

7. Atrium

2IT::.

6 7

FIGURE 3. Jerusalem, Holy Sepulchre. Reconstructed plan offourth-century complex (redrawn after Corbo with author's modifications). to similar lamps in synagogues); and the Rock of the

Crucifixion assumes the role of the altar of sacrifice on

Mount Moriah. In addition, the "Stone of the Angel" in front of the Tomb of Christ-the stone rolled from the original rock-cut tomb-is described not as round, but as a "cube," which would liken it to the Altar of Incense at the Temple.7

Such a liturgical reflection of the Temple would ac- cord with the exegetical emphasis of fourth-century Chris- tian writers; that is, it mirrors the desire of writers like

Eusebius to ground the recently accepted faith on the signs and prophesy of the Old Testament. In fact, the symbolic association of the Temple and the Sepulchre may have been initiated by Eusebius himself. In his sermon on the dedication of the church at Tyre of 317, for example,

Eusebius modeled his description of that church on Eze- kiel's vision of the Temple, and Josephus's description of the Temple as rebuilt by Herod.8 His purpose was to demonstrate the continuity from Temple to church, and to show the fulfillment of Haggai's prophecy about the Jewish

Temple that "the latter glory of this House shall be greater than the former" (Hag. 2:9).

Moreover, the language used by Eusebius to describe the discovery of the site of the Tomb of Christ and the subsequent Constantinian building project at the Holy

Sepulchre follows the same pattern. From the beginning, he refers to the site as the martyrion of the Savior's

Resurrection.9 By the end of the fourth century-and in modern scholarship-the term martyrion is used in a somewhat different sense, but Eusebius must have intended it in the same way St. Cyril explains a few decades later, namely, in reference to the prophecy of Zephaniah: "There- fore, says the Lord, wait for me at the martyrion on the day of my resurrection."'

Eusebius also preached at the dedication of the ba- silica at the Holy Sepulchre in 336. The sermon has not survived, although he noted in the Life of Constantine that he "endeavored to gather from the prophetic visions apt illustrations of the symbols it displayed."" In con- sideration of this and his references elsewhere, Wilkinson is probably correct in suggesting that Eusebius interpreted the "martyrion of the Savior" as the New Temple of

Jerusalem in the dedicatory sermon.12

The connection of the Holy Sepulchre with the Temple, then, seems to have existed from its inception, and it is seen most clearly in the shaping of the liturgy and in the language of Eusebius. Neither seems to have had a clear, architectural manifestation. Nevertheless, the association was developed in the folklore of the Early Christian period. One result was a blatant literalism: "holy sites" and relics previously associated with the Temple were gradually incorporated into the Holy Sepulchre complex.

For example, in the fourth century the Pilgrim of Bor- deaux saw on the Temple Mount "an altar which has on it the blood of Zacharias-you would think it had only been shed today," as well as the footprints of the soldiers that killed him.13 By the sixth century, the site had migrated, and the author of the Breviarius saw the "altar where holy

Zacharias was killed, and his blood dried there," in front of the Tomb of Christ.14 Sometime before the seventh

46

This content downloaded on Thu, 28 Feb 2013 18:27:22 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

century, the omphalos or navel of the world was also relocated at the Christian center.15

Events from the life of Christ associated with the

Temple were transferred as well. For example, pilgrims in the sixth century were told that the inner courtyard of the

Holy Sepulchre was the Temple court "where Jesus found them that sold the doves and cast them out.'"16

In addition,

Christian pilgrims saw the Horn of the Anointing used by the Jewish kings, the ring of Solomon, and the altar of

Abraham.

The Horn of the Anointing is an evocative relic, however untestified in the Jewish sources. It is first men- tioned by Egeria in the late fourth century, and was venerated along with the Wood of the Cross and the ring of Solomon on Good Friday."7 The ring of Solomon is perhaps more intriguing. It was apparently a seal-ring, decorated with a pentagram. According to a Jewish legend, well known in the Early Christian centuries, it was claimed to have been used by King Solomon to seal the demons and thereby gain power over them. While under his con- trol, the power of the demons was channeled to aid in the construction of the first

Temple.18

Elsewhere in the Basilica of Constantine, pilgrims saw the vessels in which Solomon had sealed the demons.19

The altar of Abraham marked the site where he had offered his son Isaac as a sacrifice on Mount Moriah, and this was commonly identified with the altar of the Temple.

The event figured prominently in Christian thought, juxta- posing the sacrifice of Abraham with that of Christ.

According to the Breviarius, the sacrifice of Abraham occurred "in the very place where the Lord was cruci- fied."20 Thus, Golgotha became Mount Moriah, and was also regarded as the place where Adam was created and where he was buried. The altar is also mentioned by the

Piacenza Pilgrim and by Adomnan, and it is represented in the Holy Sepulchre plans that accompany the texts of

Adomnan.21

After the Arab capture of Jerusalem, the Dome of the

Rock was constructed on the Temple mount, presumably on the former site of the Temple, left barren under the

Christian rule. Under Muslim rule the site again became associated with the shared theme of the Sacrifice of Abra- ham. Likewise in Muslim thought, the two sites were juxtaposed. As Muqadassi related:

Abd al-Malik, seeing the greatness of the qubba of the

Holy Sepulchre and its magnificence, was moved lest it should dazzle the minds of the Muslims and hence erected the Dome of the Rock.22

Another manifestation of the association between the

Temple and the Holy Sepulchre may be seen in the representations of the two buildings. Although there was very little similarity between the two, they are portrayed in a like manner on coins, pilgrims' souvenirs, and works of

FIGURE 4. Tetradrachm of Bar Kochba (courtesy E. J. Waddell, Ltd.). art. Both are commonly represented with architectures of two different scales: larger columns support an architrave, pediment, or dome above a smaller structure that can be identified either as the Ark of the Covenant in the Holy of

Holies or as the Tomb aedicula.

The earliest representations of the Temple may be those from coins associated with the Bar Kochba revolt of

A.D. 132-35 (Fig. 4). Four columns support the architrave of a large building, within which stands an object with an arched top. Several scholars have viewed this image as a

Torah shrine, but considering the Messianic hope of the revolt for the restoration of the Temple, as well as the conventions of Roman coinage, this should be interpreted as the facade of the Temple with the Ark of the Covenant

23 inside.23 Incidentally, many of these coins were pierced to be worn on a necklace, possibly with amuletic properties.

It is noteworthy that the coin images date from more than a half-century after the final destruction of the Temple, and long after the Ark had disappeared. Nevertheless, a tradition of visual representation seems to have been established.

The image above the Torah shrine in the Synagogue at Dura-Europos (A.D. 244-45) is virtually identical, and the narrative scene of the Sacrifice of Abraham surely indicates that this is the Temple (Fig.

5).24

And as Rosenau points out, it would be redundant to represent the Torah shrine above the Torah shrine.25 At Dura, the Ark is shown with a shell motif in its arched pediment, a detail repeated in the actual Torah shrine below. Because the shrine-the Ark of the Law-replaced the Ark of the

Covenant in Jewish thought, as synagogue worship re- placed Temple worship, it follows that the shrine should be modeled after the Ark. This has led to numerous confusions in the interpretation of Jewish imagery. In the iconographic transfer from Temple to Sepulchre, as we

47

This content downloaded on Thu, 28 Feb 2013 18:27:22 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

i

•i

)/•7low!

( iiiii!•

/I!

07? 4

g

FIGURE 6. Dumbarton Oaks Collection, Washington. Pewter pilgrims' ampulla. Holy Women at the Sepulchre (courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks).

FIGURE 5. Damascus National Museum. Synagogue of Dura-Europos, central panel and scroll niche. shall see, the synagogue may have served as an inter- mediary, just as it did in the development of the Christian worship service. Similar images are seen in the mosaic floors of several early synagogues, as at Khirbet-Susiiya

(fourth-fifth century) and Beth She'an (fifth century).26

Both include a pediment and the distinctive shell niche above the Ark.

Representations of the Holy Sepulchre in pilgrims' souvenirs are remarkably similar to the representations of the Temple. On several pilgrims' ampullae, dated ca. 600, from the collections at Monza and Bobbio, the aedicula of the Tomb of Christ is shown below a schematic represen- tation of the Anastasis Rotunda, normally with the roof supported by four columns; a similar example is in the

Dumbarton Oaks Collection (Fig.

6).27

The Tomb aedicula is topped by a pediment containing a shell motif. Differen- tiated by the form of the roof, the crosses, and the grilles at the entrance to the tomb, the images nevertheless call to mind the Ark within the Holy of Holies at the Temple.

The specific imagery of the Ark or Tomb aedicula merits further investigation. In the rock-cut tombs at

Sheikh-Ibreiq, the scallop shell is combined with an arcu- ated lintel, both recognized as symbols stressing the di- vinity or "superiority" of the deceased, or possibly the immortality of his soul, as Goodenough suggests.28

The imagery would emphasize the burial "in the law," reflect- ing either synagogue or Temple architecture.29

Similar symbolic shrines appear as windows on the south facade of the synagogue at Capharnaum, facing toward Jerusalem (Fig.

7).30

The shell niche is clearly represented, topped by a pediment or arculated lintel supported by two pairs of columns. The columns have spiral fluting, a detail that appears in several other Temple images, and on most of the Christian pilgrims' flasks. On the latter, the spiral columns may be a part of either the aedicula or the Rotunda, but they seem to have been potent and necessary symbols in the schematic representa- tions. One may recall the spiral columns at the shrine of

St. Peter in Rome, which according to legend were taken from the Temple of Jerusalem.31 In addition, similar forms appear on the sixth-century altar base from the cathedral of Ravenna, which was dedicated to the Anastasis, sugges- tive of a connection with Jerusalem.32

Perhaps closest to the original Tomb aedicula is the fragmentary stone model found in Narbonne (Fig. 8).33

48

This content downloaded on Thu, 28 Feb 2013 18:27:22 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

From this, the facade of the aedicula can be reconstructed as a pedimented arch opening to a shall niche; the colon- naded porch below was enclosed by grilles. The remaining surfaces were decorated with columns (perhaps spiral columns?). The reconstructed form of the Tomb of Christ is better seen in Wilkinson's model (Fig. 9).

The reconstructed Tomb aedicula compares nicely with another image from Capharnaum, which I think should be identified as the Ark of the Covenant in a cart, perhaps a reference to its return to Israel from the land of the Philistines (Fig.

10).34

This unique image is normally interpreted as a moveable Torah shrine or Ark of the Law, but I Kings 6 and II Kings 6 both describe the use of a cart for the eventual return of the Ark to Jerusalem.

Interpreted as such, it would have been a potent symbol in the post-Temple period. It is perhaps the only nonaxial representation of the Ark from this period, revealing colonnettes along its flank, as well as the shell motif in the pediment. Both features are also found on the Tomb aedicula.

The above discussion suggests that not only were the

Christian representations of the Tomb of Christ influenced by the Temple imagery of the period, but that the original form of the Tomb aedicula may also have borrowed from the evocative formal language of contemporaneous Jewish art. And perhaps here we should return to Eusebius, who seems to have been on hand from the beginning of official interest in the site. In his writings and presumably in his dedicatory sermon, Eusebius played a critical role in defin- ing the meaning of the Holy Sepulchre in relationship to the Temple. Could he also have influenced the selection of suitable architectural forms? As the architectural setting acted as a physical manifestation of the significance of the site and the events it commemorated, it may well be that

Eusebius also helped to establish the architectural imagery of the Tomb aedicula.

However, I am not going to push this point. It is a mistake to view these images in isolation. Pedimented arches, shell niches, and aediculae were all common ele- ments in the late Roman architectural vocabulary, particu- larly in the Near East, and these elements appear in various combinations in numerous other works of archi- tecture-as for example, the Temple of Venus at Baalbek- and even works of the minor arts, and slightly later in early Muslim mihrab niches.35 In many-if not most-- instances, these forms would seem to be part of an archi- tectural language of power or glorification. In any event, the suggestion of specificity of reference in the selection of architectural forms at the Holy Sepulchre must be tem- pered with a broader view of the architectural vocabulary of the period.

Whereas the architectural metaphor may not have been explicit, it was strengthened by Eusebius's more spe- cific literary metaphor. In addition, it further accorded with the aim of fourth-century scriptural exegesis: to

S4

.

"

.. ..

41.01 fi l

.

.11

..

0 11144114

FIGURE 7. Capharnaum, Synagogue. Reconstruction of a window frame

(after S. Loffreda, Capharnaum).

12

01

'N

PLAN

0 o ... .

?

IW M 44L114 11U 064SU U 1111

LI

.

Ilt 11%11I c COUPE X' - X

Ci o..

. o-

• r b- FACADE

(6tat actuol) 100 d-FACADE

LATtRALE

FIGURE 8. Narbonne, Musee lapidaire, no. 839. Memoria Sancti Se- pulcri (after Lauffray).

49

This content downloaded on Thu, 28 Feb 2013 18:27:22 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

..........

AMP

T9

--77"m

I

4i

FIGURE 10. Capharnaum, Synagogue. Detail offrieze showing a move- able Ark.

FIGURE 9. Jerusalem, Holy Sepulchre. Reconstructed model offourth- century Tomb aedicula (Wilkinson). validate the newly accepted religion with the prophecy of the Old Testament. The "martyrion of the Savior's Resur- rection" could be confirmed both by the writings of Zepha- niah and by the existence of the Tomb. Architecture could help to demonstrate that "the latter glory of this house shall be greater than the former."36 And through an ideological transformation, the Tomb of Christ could be- come the new Ark of the Covenant, the Holy of Holies in the New Temple. text? In his oft-quoted work, Grabar explains that a martyr was a witness for the faith, and at the time of

Eusebius, "the sacred edifice called martyrion signifies only witness, place of witness.""37 both the shrines of martyrs and the holy sites of Palestine could be called martyria: the term was thus generic from the beginning, and this is how it is used in modern scholarship. For example, Krautheimer, following Gra- bar's lead, defined martyrium as "a site which bears wit- ness to the Christian faith either by referring to an event in

Christ's life or Passion, or by sheltering the grave of a martyr, a witness by virtue of having shed his blood; the structure erected over such a site."38

However, Grabar's interpretation is a bit at odds with the few early Christian writers who explained the term.

Diechmann points out that the word was foreign and uncommon in Latin, and possibly out of date by the time of Walafrid Strabo (ca. 808-49), who gave the following definition: "martyria vocabantur ecclesiae quae in honore aliquorum martyrum fiebant."39 Isidore of Seville (ca.

560-636) followed the same pattern: "martyrium, locus martyrum, graeca derivatione, eo quod in memoriam martyris sit constructum, vel quod sepulcra ibi sint mar- tyrum."40

Both Strabo and Isidore limit their definition to the shrines of martyrs.

But what about the early fourth-century sanctuaries marking the Holy Sites of Palestine so important to

Grabar's definition and subsequent discussion? A look at the texts indicates that the only Palestinian holy site called a martyrium during the fourth century was the Holy

Sepulchre.41

This also was apparently the first site desig- nated as such, and the term had special connotations related to the site.

50

The above discussion raises another question: How did the term martyrion or martyrium begin to be used in a specifically Christian topographical or architectural con-

This content downloaded on Thu, 28 Feb 2013 18:27:22 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The term martyrion appears about 250 times in the

Septuagint, normally in a legal sense, meaning the proof of something, the evidence. When applied to a specific time or place, the term is usually expanded to he skene tou martyriou. God himself could be the martyrion, in an accusing sense and in executing judgment. Although the idea of martyrdom-that is, suffering and death for the faith-was prevalent in later Jewish thought, the martyrs of the Old Testament, strictly speaking, were those who bore witness with a message for others.42 This usage was adopted in the New Testament, in which the Apostles were witnesses in a legal sense, and the term martyrion usually referred to witness against false belief rather than the evangelistic witness of missionary preaching.43

In accordance with its objective connotations, mar- tyrion later became used to refer to a martyr's tomb.

Again, the development of this usage is problematic. As far as I have been able to determine, the first recorded use of the word martyrion to refer to a venerated Christian site seems to have been by Eusebius in the Life of Con- stantine, written around A.D. 337, in his description of the discovery of the Tomb of Christ, which he called "the venerable and most holy martyrion of the Savior's resur- rection."44 As noted above, his terminology clearly came from Zephaniah 3.8: "Therefore says the Lord, wait for me at the martyrion on the day of my resurrection. In

Greek, the verse ends,

" . . . eis hemeran anastase6s mou eis martyrion." This might also be translated as, " . . . until the day of my resurrection for a testimony"; or ".. against the day when I arise as an accuser." Both appear in modern usage, the first in the English version of the

Septuagint, and the second in the St. Joseph's Catholic

Bible.45 In the Septuagint version the words martyrion and anastasis were used, and both were to become toponyms at the Holy Sepulchre. About 350, St. Cyril refers to the same passage in his Catecheses:

Now for what reason is this place of Golgotha and of the Resurrection called not a church like the rest of the churches, but a martyrion? It was perhaps because of the prophet who said: "in the day of my resurrection at the martyrion."46

What may appear to us as a rather obscure reference concurs with the aim of contemporaneous scriptural exe- geses: to validate the newly accepted religion with the prophecy of the Old Testament. But in both Eusebius and

Cyril, the meaning of Zephaniah has been altered. In

Zephaniah, the Lord will execute judgment. And the place of judgment will be His holy mountain, where the Temple is located. In Eusebius, there may be a hint of the New

Testament meaning of witness against false belief, because the term martyrion is first introduced immediately follow- ing an account of the destruction of the shrine of Aphro- dite on the site, "defiled as it was by devil-worship."47

The

Tomb of Christ thus became a testimony both for the

Resurrection and against false gods. Eusebius did not mean simply "tomb of the martyr," although Cyril's expla- nation may be headed in that direction: he clearly inter- prets the term as a special name for a building. Thus, in the writings of both Eusebius and Cyril, martyrion had a specific meaning in relationship to the site.

By the end of the fourth century, Eusebius's complex meaning had been lost. The pilgrim Egeria (ca. 385) associated the term martyrium with the Constantinian basilica, explaining that it was known as such "because it is on Golgotha behind the Cross, where the Lord was put to death."48 Notably it was the basilica, not the ro- tunda with its signative shape, that was to be called the martyrium.

By the second half of the fourth century, it seems, the term was in use to refer to martyrs' shrines and places of martyrdom. Egeria's misunderstanding removed any speci- ficity from the term martyrion as it applied to the holiest site in Christendom, and the rich associations of the term were subsequently forgotten. With the meaning introduced by Eusebius, as a part of an extended metaphor, the Holy

Sepulchre could be regarded as a martyrion in a very special sense: it could become the New Temple of Jeru- salem by supplanting the "place of judgment" of Old

Testament prophecy. And even though Eusebius's literary metaphor was forgotten, the association of the two sites persisted in Early Christian thought.

* * *

Buildings to commemorate the saints and buildings to honor the events in Christ's life may have borrowed from the same architectural language of glorification, but it would seem that they were viewed differently. The term martyrium did not originally refer to a specific building type-nor for that matter did the term basilica. In the twentieth century, such typological associations, as well as the belief that form must reflect function, have imposed a false sense of order on the study of Early Christian architecture. Frequently form could act as a signifier of general symbolic meanings, but our interpretations must be tempered with a careful reading of the available textual evidence.

This, I should note, is the warning given by Kraut- heimer in his "Introduction to an 'Iconography of Medi- eval Architecture.'"49 But does the architectural image necessarily carry the same level of meaning as the literary metaphor? In his paper, Krautheimer considered why the majority of Early Christian baptisteries were centrally planned and normally were octagonal. Looking at the ceremony of baptism, as well as numerous Early Christian writers' interpretations of the ceremony, he stressed that the rite of Christian initiation ceremonially reenacted the burial and resurrection of Christ. Going one step further, he suggested that the same meaning was manifest in the architecture, that is, that the baptistery as a building type

51

This content downloaded on Thu, 28 Feb 2013 18:27:22 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

was modeled after the form of the Anastasis Rotunda at the Holy Sepulchre.

But whereas the meaning of the ceremony is made explicit through its language, no surviving text states that an Early Christian baptistery was a copy of a specific building. Moreover, there is nothing explicit in the archi- tectural form of any of these buildings to establish a link with the Holy Sepulchre. On the other hand, there would seem to have been a general, typological association of the octagonal baptistery with a common form of late Roman imperial mausoleum, and this would have emphasized the association between baptism and death.5 The relationship with the death of Christ is established in only the most general terms through the architecture, whereas the sym- bolism of the baptismal ceremony is much more specific.

Thus, architecture may comment on or interact with the rituals it houses, but I think it is a mistake to expect a direct symbolic correspondence. In the architectural setting, there was perhaps by necessity only a general association of form and meaning. It was the function-the liturgy-that added texture, nuance, and specificity.

On the basis of the above discussion, I think we can see a similar relationship between form and function emerg- ing at the Holy Sepulchre. The associations with the

Temple were developed only in a general way with respect to the architecture, but they became more specific in the liturgy, as well as in the writings of Eusebius and St. Cyril.

Whereas a comparison seems invited, nowhere are we told that the Holy Sepulchre was a "copy" of the Temple. Such a blatant equation would have proved limiting and would not have resonated with the other, equally important, messages of the building, such as the victory of the church, the active involvement of the imperial family, and the order and harmony of the Christian cosmos. The archi- tectural setting had to provide a symbolic framework in which many associations could be evoked and could exist simultaneously. Clearly, the understanding of the liturgical service and of the literary metaphor can aid in the inter- pretation of architectural form, but in the final analysis, words and images, ceremonies and settings, communicate in different ways.

NOTES

*

The following study owes much to John Wilkinson, whom I grate- fully acknowledge for his continued friendship and encouragement.

Earlier versions were presented at the 1988 Annual Meeting of the

Society of Architectural Historians in Chicago and at the University of Chicago Colloquium on Art, Liturgy, and Music in 1989.

1. Eusebius, Vita Constantini, 3.28, trans. J. Wilkinson, Egeria's Tra- vels to the Holy Land (Warminster, 1981), 164-71. Note also the discussion by J. Z. Smith, To Take Place. Toward Theory in Ritual

(Chicago, 1987), 74-95: "Eusebius has here invited us to compare the Constantinian foundation with the temple in Jerusalem . .

. We should accept the invitation" (p. 83).

2. R. Krautheimer, "Introduction to an 'Iconography of Medieval

Architecture,"' JWCI, V (1942), 1-33, reprinted in R. Krautheimer,

Studies in Early Christian, Medieval, and Renaissance Art (New

York, 1969), 115-50. More recently, see my comments in R. Ouster- hout, "The Church of S. Stefano: A 'Jerusalem' in Bologna," Gesta,

XX (1981), 311-21; idem, "Meaning and Architecture: A Medieval

View," Reflections, 2 (1984), 34-46; and idem, "Loca Sancta and the Architectural Response to Pilgrimage," The Blessings of Pil- grimage, ed. R. Ousterhout (Urbana-Chicago, 1990), 108-24.

3. The literature on the Temple is voluminous: see B. Narkiss,

"Temple," Encyclopaedia Judaica, 1971, XV, cols. 942-88, for a convenient summary with extensive bibliography. For a popular survey, see J. Comay, The Temple of Jerusalem (New York, 1975); for the influence of the Temple in the visual arts, H. Rosenau,

Vision of the Temple. The Image of the Temple of Jerusalem in

Judaism and Christianity (London, 1979).

4. V. Corbo, II Santo Sepolcro di Gerusalemme (Jerusalem, 1981); also L. H. Vincent and F.-M. Abel, Jfrusalem Nouvelle, II (Paris,

1914). For the state of scholarship, see R. Ousterhout, "Rebuilding the Temple: Constantine Monomachus and the Holy Sepulchre,"

JSAH, XLVIII (1989), 66-78, esp. 66-67 and notes 1-6.

5. Egeria, 48.1 (Wilkinson, Egeria's Travels, 146).

6. J. Wilkinson, "Jewish Influences on the Early Christian Rite of

Jerusalem," Le Musion, XCII (1979), 347-59; idem, Egeria's Tra- vels, 298-310.

7. Idem, "Jewish Influences," 357; see the accounts of Theodosius, de

Situ Terrae Sanctae, 28, and Sophronius, Anacreonticon, 20.12:

J. Wilkinson, Jerusalem Pilgrims before the Crusades (Warminster,

1977), 70-71 and 91.

8. J. Wilkinson, "Paulinus' Temple at Tyre," Jahrbuch der Oster- reichischen Byzantinistik, XXXII/4 [Akten 11/4, XVI. Internation- aler Byzantinistenkongress], 553-61. For the relationship of the writings of Eusebius to Constantine, see T. Barnes, Constantine and

Eusebius (Cambridge, Mass., 1981).

9. V. Const., 3.28 (Wilkinson, Egeria's Travels, 165).

10. See Wilkinson, Egeria's Travels, 324, note to p. 165.

11. V. Const., 4.45 (Wilkinson, Egeria's Travels, 302).

12. Wilkinson, "Jewish Influences," 351-52.

13. Pilgrim of Bordeaux, 591 (Wilkinson, Egeria's Travels, 157).

14. Breviarius, 3 (Wilkinson, Jerusalem Pilgrims, 60).

15. Adomnan, de Locis sanctis, 1.11.4; Bernard the Monk, 12 (Wilkin- son, Jerusalem Pilgrims, 99 and 144).

16. Breviarius, 3 (Wilkinson, Jerusalem Pilgrims, 60).

17. Egeria, 37.3 (Wilkinson, Egeria's Travels, 137).

18. See G. Vikan, Byzantine Pilgrimage Art (Washington, 1982), 35 and fig. 27; C. C. McCown, The Testament of Solomon (Leipzig, 1927),

10.

19. Breviarius, 2 (Wilkinson, Jerusalem Pilgrims, 59).

20. Ibid., 60.

21. Piacenza Pilgrim, 19; and Adomnan, 6.2 (Wilkinson, Jerusalem

Pilgrims, 83 and 97). For the plans, see Wilkinson, Jerusalem

Pilgrims, 195-97 and pls. 5-6.

22. O. Grabar, The Formation of Islamic Art (New Haven, 1973), 64-

65. The Arabic word qubba means tomb or domed tomb, but

Grabar translates it as martyrium.

23. A. Reifenberg, Ancient Jewish Coins (Jerusalem, 1973), 36; but see

Y. Meshorer, Jewish Coins of the Second Temple Period (Tel Aviv,

52

This content downloaded on Thu, 28 Feb 2013 18:27:22 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1967), 93-94, who notes the special importance of the Temple during the Bar Kochba revolt.

24. C. H. Kraeling, et al., The Excavations at Dura Europos, Final

Report, VIII, i. The Synagogue (New Haven, 1956), 390ff.

25. H. Rosenau, Vision of the Temple, 20-21.

26. Ibid., 22-23, and figs. 13-14.

27. A Grabar, Ampoules de Terre Sainte (Paris, 1958): Monza 13 and

14; Bobbio 3 and 15. M. C. Ross, Catalogue of the Byzantine and

Early Mediaeval Antiquities in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection, I.

Metalwork, Ceramics, Glass, Glyptics, Painting (Washington, 1962), no. 87.

28. E. R. Goodenough, Jewish Symbols in the Greco-Roman Period

(New York, 1953-65), I, 93; VIII, 95-104; see also D. F. Brown,

"The Arcuated Lintel and Its Symbolic Interpretation," American

Journal of Archaeology, XLVI (1942), 389-99.

29. S. Ferber, "The Pre-Constantinian Shrine of St. Peter: Jewish

Sources and Christian Aftermath," Gesta, X (1971), 11-14.

30. E. L. Sukenik, Ancient Synagogues in Palestine and Greece (Lon- don, 1934), 7-21; Goodenough, Jewish Symbols, I, 184. The chro- nology of the Capharnaum synagogue is problematic; see most recently M. Fischer, "The Corinthian Capitals of the Capernaum

Synagogue: A Revision," Levant, XVIII (1986), 131-42, with exten- sive bibliography, who argues for a date in the middle of the third century based on the style and materials of the architectural orna- ment. The excavators, V. Corbo, S. Loffreda, and A. Spijkerman,

La sinagoga di Cafarnao dopo gli scavi del 1969 (Jerusalem, 1970), passim, had tentatively proposed a date after the beginning of the fifth century.

31. J. B. Ward Perkins, "The Shrine of St. Peter and Its Twelve Spiral

Columns," Journal of Roman Studies, XLII (1952), 21-33.

32. Ferber, "Pre-Constantinian Shrine," 24-25 and fig. 31.

33. J. Lauffray, "La Memorial Sancti Sepulcri du Musee de Narbonne et le Temple Rond de Baalbeck," MWlanges de l'Universite St.

Joseph, XXXVIII (1962), 199-217; J. Wilkinson, "The Tomb of

Christ: An Outline of Its Structural History," Levant, IV (1972),

91-96.

34. This is normally interpreted as a moveable Torah shrine or Ark of the Law; see Goodenough, Jewish Symbols, I, 184.

35. For Baalbek, see Lauffray, "La Memoria Sancti Sepulcri," and

F. Ragette, Baalbek (Park Ridge, N.J., 1980), 55-61. For a work in the minor arts, see the Syro-Palestinian mirror frame from the collection of the University of Chicago Divinity School, E. D.

Maguire, H. Maguire, and M. Duncan-Flowers, Art and Holy

Powers in the Early Christian House (Champaign, 1989), 218. A carved Abbasid mihrab in the Baghdad museum has similar details; see O. Grabar, Formation, 69.

36. Haggai 2:9, cited by Eusebius, Hist. Eccl., 10.4.3; see Wilkinson,

"Jewish Influences," 350-51.

37. A. Grabar, Martyrium: Recherches sur le culte des reliques et l'art chritien antique (Paris, 1943-46), I, 29.

38. R. Krautheimer, Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture, 4th rev. ed. (Harmondsworth, 1986), 519.

39. "Churches that were built in honor of certain martyrs were called martyria." F. W. Deichmann, "Mirtyrerbasilika, Martyrion, Me- moria und Altargrab," Rimische Mitteilungen, LXXVII (1970),

144-69, esp. 149; Strabo, de reb. eccl., 6 (DuCange, V, 292).

40. "Martyrium, place of the martyrs, of Greek derivation. Because it was constructed in honor of martyrs or because the tombs of martyrs were there." Isidore, Etymologiae, xv.4: W. M. Lindsay,

Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi (Oxford, 1911); H. Leclercq, "Mar- tyrium," Dictionnaire d'archeologie et de liturgie, X.2, cols. 2512-

23, esp. 2515-17 for texts; see also G. W. Lampe, A Patristic Greek

Lexicon, 829-30.

41. The only other fifth-century references appear in the problematic

Life of St. Melanie the Younger (ca. 430): a martyrion at the site of the Ascension and the martyrion of H. Phokas in Sidon: Vita S.

Melaniae lunioris in D. Baldi, Enchiridion Locorum Sanctorum

(Jerusalem, 1982), 314, 391; A. D'Als, "Les deux vies de Sainte

Melanie la jeune," Analecta Bollandiana, XXV (1906), 401). Deich- mann, "Mirtyrerbasilika," 146-55, discusses the problematic usage of the word elsewhere in the same Vita.

42. H. Strathmann, "martus ktl." Theological Dictionary of the New

Testament, ed. G. Kittel (Grand Rapids, MI, 1967), IV, 474-508.

43. Ibid., 486.

44. V. Const., 3.28 (Wilkinson, Egeria's Travels, 165).

45. This was understood slightly differently by Jerome, In Sophon- iam, 10.12.325-327: "In die resurrectionis meae in futurum... in testimonium."

46. Catech., 14.10: L. P. McCauley and A. J. Stephenson, in Fathers of the Church (Washington, 1969).

47. V. Const., 3.27 (Wilkinson, Egeria's Travels, 165).

48. Egeria, 30.1 (Wilkinson, Egeria's Travels, 132); see Wilkinson,

"Jewish Influences," 358-59, that Egeria did not understand Euse- bius's meaning of the term "martyrium," nor his association of the

Holy Sepulchre with the Temple.

49. As above, n. 2.

50. See the comments by J. B. Ward-Perkins, "Imperial Mausolea and

Their Possible Influence on Early Christian Central-Plan Buildings,"

JSAH, XXV (1966), 297-99.

53

This content downloaded on Thu, 28 Feb 2013 18:27:22 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions