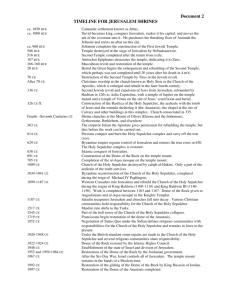

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre

advertisement