View PDF - Columbus Bar Association

advertisement

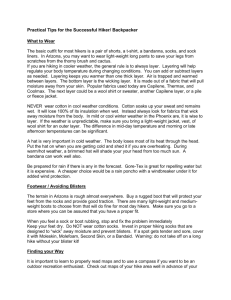

Continued from Page 21 are better equipped to help minority attorneys remedy these issues, and better yet, to help the law firm as a whole address these issues before they begin. So the good that we have in place already – our diversity and inclusion committees, our mission statements, our targeted scholarships – must be focused not only on the shark bites, but on the mosquito bites, as well. What are the little problems that can aggregate over time, go unaddressed, and hurt our attorneys and our culture? And what are the steps we can take to make our firms more open, more fair, and more aware of the culture we are all striving to achieve? There is no reason that Columbus’s legal community cannot be a national leader on this front. The Columbus Bar’s Minority Clerkship program for “African American, Asian, Hispanic and Native American law students” is a wonderful model; the Managing Partners’ Diversity Initiative is another; and many affinity bar associations are doing important work, such as at APABA-CO and the John Mercer Langston Bar Association. Our community’s efforts must continue, however, because the efforts are working in at least one measurable way: Between 2000 and 2011, the participating law firms saw an increase in minority partners from 14 to 30, and in minority associates from 31 to 42, and in minority summer associates from 18 to 37. The progress is good but insufficient as we continue to work toward more open, more fair, and more aware workplaces across the city. The end result will not just be a better legal community in which to work, for each and all of us, but an improved work product for clients that will benefit from a wider range of perspectives and approaches to applying the law. Michael Corey, Bricker & Eckler mcorey@bricker.com 22 Summer 2014 Columbus Bar Lawyers Quarterly Nature, Privacy, Comradery Keep Bringing Us Back By The Honorable David E. Cain Just the sound of certain words can stir strong emotions. Their mere mention can cause a person momentarily to relive a time of peace or pain. Immediate reactions can be fight or flight. The speaker can innocently spur the hearer’s heart to quiver, the knees to shake. For me, the words simply name a place: The Smoky Mountains. Tens of thousands of grueling footsteps, pounding chest and gasping lungs, sore muscles and sleepless fatigue. Those are the images that flash before my eyes when someone says, “Smoky Mountains.” But glorious sights and smells, the privacy of the wilderness, the challenges and the comradery keep bringing us back, back to the backpack trails. For my brother, Greg, and me, this was the 27th year in a row that we have done the “death march” – in the Smokies or someplace like them – as it came to be known in the early years, the late 1980s. More than 40 individuals have joined us in one year or another – some frequent fliers, some one-timers. The hike has always been 20 to 30 miles over a span of three or four days – in a loop back to the starting place or down a trail leading to a couple vehicles we have left at the intended destination in advance. We carried all our provisions on our backs. The last couple of years, we have tried to have it an easier way. Pleasure without pain. Sights without soreness. Base-camping instead of backpacking. Day hikes with day packs. Shed 30 or 40 pounds. Our excuse was that we were breaking in a young one. Last year, it also allowed our cousin, Stan Jones, who has driven from St. Louis to join us in 21 of the last 24 years, to bring his friend, Steve Lowery, a lifelong nonsmoker who was in his last weeks of terminal lung cancer. He couldn’t hike, but he enjoyed the woods, the campfire, the roasted brussel sprouts. It was one of his last good memories, and right up to the end (he died about three months later) he talked about going on the next one, Stan reported. Last year’s campsite was on the rim of the Linville River Gorge in the northwest corner of North Carolina. The vehicles were parked on a gravel road about a quarter mile down a fairly steep slope. This year, we did “Cadillac camping” – setting up huge tents near our trucks and a privy – in the Elkmont Campground operated by the U.S. Park Service about seven miles southeast of Gatlinburg in Tennessee. A short drive gets you to the trailhead for Mt. LaConte to the east or to Clingman’s Dome to the southeast. Both brought back raging memories of death marches past. Twenty years ago, we went up LaConte on a Thursday, the first day of an arduous 25-mile journey that would get us back to our cars by Sunday morning. The night before the hike began, John Cochran, my brother-inlaw’s son-in-law’s brother, showed me a hardened steel, curved knife so big and nasty that I refused to even hold it. The next day, he managed to get it secured behind his pack. He also found someplace to stash a quart of whiskey. Not too long after he started using both at the top of LaConte, he buried the tip of the machete-type knife just off to the side above his knee. Cut it to the quick. So, he washed it with the whiskey and wrapped it with a rag. “If it’s still bleeding tomorrow night, I’ll have to sew it up with fishing line. Had to do that for a friend of mine after he fell on some rocks in Joyce Kilmer. Hurts like hell, but it gets the job done.” Fortunately, the blood clotted despite a 12-mile hike the next day. Car camping is much different. The tent is large enough to allow sleeping on a cot. You can stand up and slip on your boots rather than crawling out of a sleeping bag onto the cold wet ground where you try to pull them on while in a fetal position. Water is always the number one concern for a backpacker. In the old days, we dipped it out of the streams and rivers and either boiled it or added iodine tablets which turned it brown and foul tasting. Then came water filtering systems that over the years became smaller and less clumsy. With car camping, you can just walk to the nearest faucet and turn it on. When one wakes to the sound of rain on the tent while backpacking (not too uncommon since we always hike in April) one leaps out of the sleeping bag and scurries about trying to keep things dry. A car camper just turns over and goes back to sleep. Backpackers hoist all food items in waterproofed bags far out on a high limb to protect their food – and bodies – from bears and other creatures. (The Great Smoky Mountains National Park has one of the largest populations of black bears as any similar sized area in North America.) Car campers just throw the food into their cars. After hundreds of hours of sitting around campfires and searching for the meaning of life, about all we have decided is that we were in the right setting to discuss such issues. “I’ve had more spiritual experiences in the mountains than in church,” Jim DeLoatch commented. Jim actually started hiking with my brother before I did and has made it for nearly all our trips. He recently retired from the North Carolina parole authority and bought a house in the mountains near Ashville. The campfire chatter also usually involves repeating some of our backpack lore, adventure stories that likely resulted from bad judgment, bad weather or bad maps. Like our first day of our first hike. Our late brother-in-law, David Shooter, Greg and I attacked the Linville River Gorge from the opposite side and down river from where we camped last year. Judge Michael Holbrook, then a practicing attorney, heard me discussing the gorge, told me he was familiar with the area and advised me to carry a big stick to throw snakes off the trail. With such a stick in hand and what seemed like a 100 pounds on my back, we started out looking from the head of a primitive trail that we never did find. Scarcely an hour into the gorge and we were trapped in brush so thick we had to crawl. The backpack and the stick were dragging behind me. Had I seen a snake, I could have only perhaps spit on it. The five-mile, 2500-foot hike up Mt. LaConte (second highest point in the Smokies) didn’t seem any easier than 20 years ago, even without the backpack. But the overlooks are still spectacular (probably the best in the Smokies) except they were dimmed by the highly overcast day this time around. Clingman’s Dome is accessible by a snaking highway with numerous pull offs for sight- seeing and is a popular tourist attraction. An observation tower – with a circling ramp for an easy climb – is at the tippy top of the dome and boasts of being the highest point in all the Smokies (a total of 6643 feet above sea level). The dome still had patches of ice and snow, but lower trails were already colorful with patches of the big- blossomed white and yellow trilliums, tiny thyme-leaved bluets, purple phlox, and purple and yellow violets. Rounding out the group this year were my son-in-law, Kenny Mullins of Columbus; my sister-in-law’s son-in-law, Michael Bailey, and his 8-year-old son, Jackson, of Akron; Michael’s friend, Paul Crilley of Erie, Pa.; and Greg’s son, Nick, whose first of many hikes was in 1994 when he was nine years old. My grandson, Lincoln Mullins, 14, (a regular since he was seven years old) brought his friend, Skye Payne, also 14. Those two usually had a plan: “We’re hiking on up till we get a (cell phone) signal.” We decided we will definitely backpack (no car camping) again next year. And it is not just the guilt feelings, the need for more privacy or a double dare. At this point, it’s tradition. So far, it has served as an “acid test” for future sons in law. Now, it’s a right of passage for their offspring. War stories have become folklore and painful hours have become sweet memories. The Honorable David E. Cain, Franklin County Common Pleas Court David_Cain@fccourts.org Summer 2014 Columbus Bar Lawyers Quarterly 23