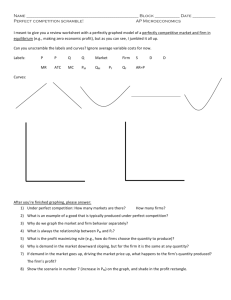

Econ 201 Lecture 17 The Perfectly Competitive Firm Is a Price Taker

advertisement

Econ 201 Lecture 17 The Perfectly Competitive Firm Is a Price Taker (Recap) The perfectly competitive firm has no influence over the market price. It can sell as many units as it wishes at that price. Typically, a "perfectly" competitive industry is one that consists of a large number of sellers, each of which makes a highly standardized product. An example is corn production. Profit-maximization for the perfectly competitive firm Profit = Total revenue - total cost Q. How much output should a perfectly competitive firm produce if its goal is to earn as much profit as possible? A. It should keep expanding output as long as the marginal benefit of doing so exceeds the marginal cost. The marginal benefit of expanding output by one unit is the market price. The marginal cost of expanding production by one unit is the firm's marginal cost at its current production level. Example 17.1. Consider a corn grower whose marginal cost of growing corn is labeled MC in the diagram. If this grower can sell as many bushels of corn as he chooses to at a price of $5 per bushel, how many bushels should he sell in order to maximize profit? $/bushel Marginal cost of producing corn 6 5 4 Price 6 9 12 Thousands of bushels of corn/yr The profit-maximizing quantity for the perfectly competitive firm is the one for which price = MC. Imperfect Competition Monopoly = "single seller" Example: Time Warner Cable in the Ithaca market for cable TV service Oligopoly = "few sellers" Example: AT&T, Sprint, and MCI in the market for long-distance telephone service Monopolistic competition: Many sellers, each with a differentiated product Example: Local gasoline retailing Five Sources of Monopoly 1. Exclusive control over important inputs Example: Perrier's mineral spring 2. Economies of Scale (Natural monopoly) Example: Local telephone service 3. Patents Example: Polaroid cameras & film 4. Government licenses or franchises Example: Burger King on Mass Pike 5. Network Economies Example: Microsoft Windows 2 Most enduring source of monopoly is economies of scale. Scale Advantage in the Old Economy Two widget producers, Acme and Ajax, each have fixed costs of $200,000, and variable costs of $0.80 per widget. Acme annual production: 1,000,000 units fixed costs: $200,000 variable costs: $800,000 total costs: $1,000,000 cost per widget: $1.00 Ajax, the high volume producer, has only a small cost advantage. Ajax 1,200,000 units $200,000 $960,000 $1,160,000 $0.97 Scale Advantage in the New Economy In the new economy, fixed costs are $800,000, reflecting the growing importance of the information and ideas in the product. Variable costs are only $0.20/widget. Acme annual production: 1,000,000 units fixed costs: $800,000 variable costs: $200,000 total costs: $1,000,000 cost per widget: $1.00 Now Ajax has a much larger cost advantage. Ajax 1,200,000 units $800,000 $240,000 $1,040,000 $0.87 This cost advantage becomes self reinforcing, as more and more of the market goes to Ajax: Acme annual production: fixed costs: variable costs: total costs: cost per widget: 500,000 units $800,000 $100,000 $900,000 $1.80 Ajax 1,700,000 units $800,000 $340,000 $1,140,000 $0.67 Monopoly, oligopoly, and monopolistically competitive firms have in common the fact that the demand curves for their goods are downward sloping. Price D Quantity For convenience, we will refer to any of these three types of imperfectly competitive firms as monopolists. The demand curve facing a perfectly competitive firm is a straight line at the market price. $/unit of output Market Price D Quantity 3 Marginal Revenue The marginal benefit to a competitive firm of selling an additional unit of output is the market price. By contrast, the marginal benefit to a monopolist of selling an additional unit of output is less than the market price. The reason is that it must cut its price in order to sell an extra unit of output, and this means that it will earn less on the output is was selling thus far. Example 17.2. A monopolist with the demand curve shown in the diagram is currently selling 3 units of output at a price of $7 per unit. What is its marginal benefit from selling an additional unit? Price 10 7 6 D 3 4 10 Total revenue from the sale of 3 units = $7x3 = $21 Quantity Total revenue from the sale of 4 units = $6x4 = $24 So marginal revenue from the fourth unit is $3, which is less than both the original price and the new price. Example 17.3. A monopolist with the demand curve shown in the diagram is currently selling 4 units of output at a price of $6 per unit. What is its marginal benefit from selling an additional unit? Price 10 6 5 D 4 5 10 Total revenue from the sale of 4 units = $6x4 = $24 So marginal revenue from the fifth unit is $1. Quantity Total revenue from the sale of 5 units = $5x5 = $25 Example 17.4. A monopolist with the demand curve shown in the diagram is currently selling 5 units of output at a price of $5 per unit. What is its marginal benefit from selling an additional unit? Price 10 5 4 D 5 6 Total revenue from the sale of 5 units = $5x5 = $25 So marginal revenue from the sixth unit is -$1 The Marginal Revenue Curve for a Monopolist For the monopolist in the preceding examples: 10 Quantity Total revenue from the sale of 6 units = $6x4 = $24 4 Price 10 5 MR D Quantity 5 10 For any monopolist with a straight-line demand curve: Price a a/2 MR Quantity Q0 Q0 /2 For a straight-line demand curve: P = a - bQ The corresponding MR curve: MR = a - 2bQ For calculus-trained students: MR = dTR/dQ TR = PQ = aQ-bQ2 MR = a - 2bQ so Example 17.5. Find the marginal revenue curve for the monopolist whose demand curve is given by D in the diagram. Price Price 8 8 4 D D Quantity 16 Quantity 8 MR 16 Profit-maximization for the monopolist Profit = total revenue - total cost Q. How much output should a monopolist produce if its goal is to earn as much profit as possible? A. It should keep expanding output as long as the marginal benefit of doing so exceeds the marginal cost. The marginal benefit of expanding output by one unit is marginal revenue at the current output level. The marginal cost of expanding production by one unit is the firm's marginal cost at the current output level. Example 17.6. Consider a monopolist with the demand and marginal cost curves shown in the diagram. 5 True or False: The profit-maximizing level of output for this monopolist is 9 units. $/unit of output 12 $/unit of output 12 Marginal cost Marginal cost 8 6 4 6 D D Quantity 9 Quantity 6 18 9 18 At 9 units of output, marginal cost is 6 and marginal revenue is zero. Therefore the gain from contracting output ($6/unit) is less than the loss from contracting output ($0/unit). And this means that the monopolist cannot be maximizing profit at a quantity of 9 units. The profit-maximizing quantity for the monopolist is the one for which MR = MC, in this case 6 units of output. At that level of output the monopolist will charge a price of $8/unit. Example 17.7. Consider the profit-maximizing monopolist in Example 17.6. At the profit-maximizing level of output, what is the benefit to society of an additional unit of output? What is the cost to society of an additional unit? Is this situation efficient from society's point of view? $/unit of output 12 Marginal cost 8 6 4 D Quantity 6 9 18 The marginal benefit to society of an additional unit of output is $8. The marginal cost of an additional unit is only $4. This means that society would gain a net benefit of $4 per unit of output if output were expanded from the profit-maximizing level. Note that the monopolist would love to expand output if it could do so without having to sell the current output at a lower price. Example 17.8. If this monopolist maximizes profit, by how much will total economic surplus be smaller than the maximum possible economic surplus? Price 12 MC 6 D 9 18 Quantity Maximum possible economic surplus = CS + PS 6 Consumer surplus P MC Producer surplus 12 6 D Q 18 9 Loss in economic surplus from monopoly: P 12 Consumer Producer surplus surplus MC 8 Loss in surplus 6 4 D 6 9 MR 18 Q