Adam Liptak, At Heart of Health Law Clash, a 1942 Case of a

advertisement

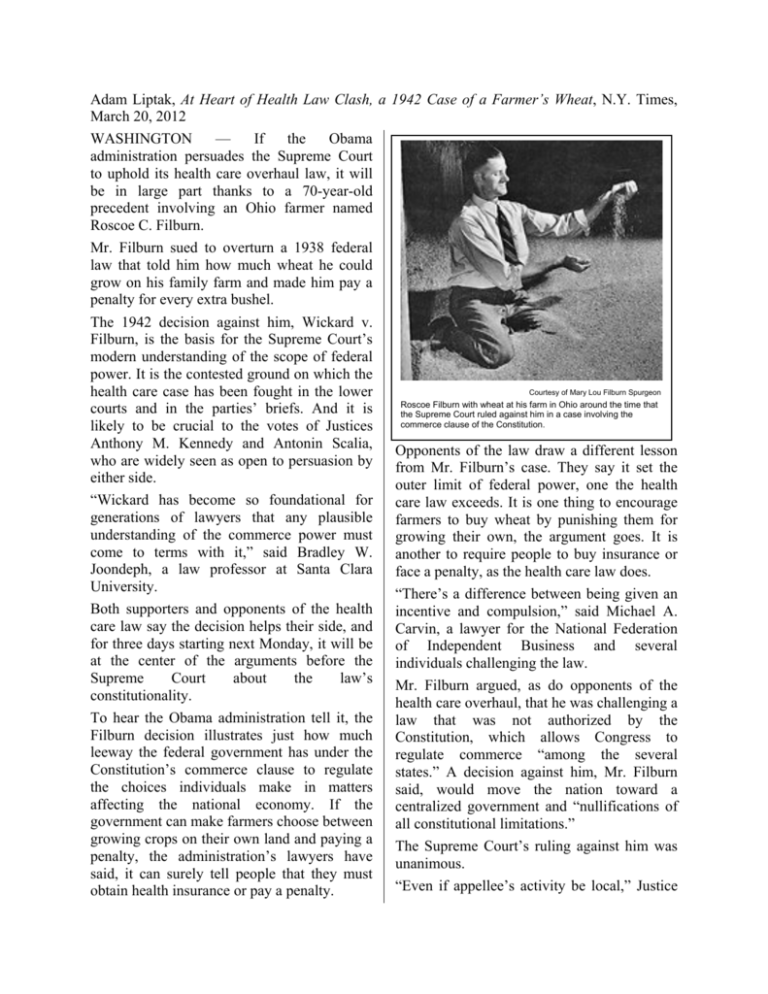

Adam Liptak, At Heart of Health Law Clash, a 1942 Case of a Farmer’s Wheat, N.Y. Times, March 20, 2012 WASHINGTON — If the Obama administration persuades the Supreme Court to uphold its health care overhaul law, it will be in large part thanks to a 70-year-old precedent involving an Ohio farmer named Roscoe C. Filburn. Mr. Filburn sued to overturn a 1938 federal law that told him how much wheat he could grow on his family farm and made him pay a penalty for every extra bushel. The 1942 decision against him, Wickard v. Filburn, is the basis for the Supreme Court’s modern understanding of the scope of federal power. It is the contested ground on which the Courtesy of Mary Lou Filburn Spurgeon health care case has been fought in the lower Roscoe Filburn with wheat at his farm in Ohio around the time that courts and in the parties’ briefs. And it is the Supreme Court ruled against him in a case involving the commerce clause of the Constitution. likely to be crucial to the votes of Justices Anthony M. Kennedy and Antonin Scalia, Opponents of the law draw a different lesson who are widely seen as open to persuasion by from Mr. Filburn’s case. They say it set the either side. outer limit of federal power, one the health “Wickard has become so foundational for care law exceeds. It is one thing to encourage generations of lawyers that any plausible farmers to buy wheat by punishing them for understanding of the commerce power must growing their own, the argument goes. It is come to terms with it,” said Bradley W. another to require people to buy insurance or Joondeph, a law professor at Santa Clara face a penalty, as the health care law does. University. “There’s a difference between being given an Both supporters and opponents of the health incentive and compulsion,” said Michael A. care law say the decision helps their side, and Carvin, a lawyer for the National Federation for three days starting next Monday, it will be of Independent Business and several at the center of the arguments before the individuals challenging the law. Supreme Court about the law’s Mr. Filburn argued, as do opponents of the constitutionality. health care overhaul, that he was challenging a To hear the Obama administration tell it, the law that was not authorized by the Filburn decision illustrates just how much Constitution, which allows Congress to leeway the federal government has under the regulate commerce “among the several Constitution’s commerce clause to regulate states.” A decision against him, Mr. Filburn the choices individuals make in matters said, would move the nation toward a affecting the national economy. If the centralized government and “nullifications of government can make farmers choose between all constitutional limitations.” growing crops on their own land and paying a The Supreme Court’s ruling against him was penalty, the administration’s lawyers have unanimous. said, it can surely tell people that they must “Even if appellee’s activity be local,” Justice obtain health insurance or pay a penalty. Robert H. Jackson wrote, referring to Mr. Filburn’s farming, “and though it may not be regarded as commerce, it may still, whatever its nature, be reached by Congress if it exerts a substantial economic effect on interstate commerce.” The Obama administration says the decisions of millions of people to go without health insurance have a similarly significant effect on the national economy by raising other people’s insurance rates and forcing hospitals to pay for the emergency care of those who cannot afford it. At the time, the reaction to the Filburn decision emphasized how much power it had granted the federal government. “If the farmer who grows feed for consumption on his own farm competes with commerce, would not the housewife who makes herself a dress do so equally?” an editorial in The New York Times asked. “The net of the ruling, in short, seems to be that Congress can regulate every form of economic activity if it so decides.” The editorial, like much commentary on the case, seemed to suppose that Mr. Filburn was a subsistence farmer. But in fact he sold milk and eggs to some 75 customers a day, and the wheat he fed to his livestock entered the stream of commerce in that sense, according to a history of the case by Jim Chen, the dean of the law school at the University of Louisville. In the health care case, the administration has insisted that the overhaul law is a modest assertion of federal power in comparison to the law Mr. Filburn challenged. “The constitutional foundation for Congress’s action is considerably stronger” for the health care law than for the law that the Supreme Court endorsed in 1942, the administration said in a recent brief. The health care law, the brief said, merely “regulates the way in which the uninsured finance what they will consume in the market for health care services (in which they participate).” Opponents of the law take the opposite view, using an analogy. It is true that the federal government may “regulate bootleggers because of their aggregate harm to the interstate liquor market,” Mr. Carvin wrote in a recent brief. But the government “may not conscript teetotalers merely because conditions in the liquor market would be improved if more people imbibed.” “Yet the uninsured regulated by the mandate,” the brief went on, “are the teetotalers, not the bootleggers, of the health insurance market.” For more than 50 years after ruling against Mr. Filburn, the Supreme Court did not strike down any federal laws on commerce clause grounds. But in a pair of 5-to-4 decisions, in 1995 and 2000, the court invalidated two laws, saying the activities that Congress had sought to address — guns near schools and violence against women — were local and noncommercial and thus beyond its power in regulating interstate commerce. The decisions were part of a renewed interest in federalism associated with Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist, who died in 2005, and Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, who retired in 2006. Those two justices were still on the court in 2005 when it issued its last major commerce clause decision, Gonzales v. Raich. That decision was 6 to 3 in favor of upholding a federal law regulating home-grown medicinal marijuana. Chief Justice Rehnquist and Justice O’Connor dissented, as well as Justice Clarence Thomas. But Justices Scalia and Kennedy, who had voted to strike down the laws at issue in the 1995 and 2000 cases, were in the majority. “The similarities between this case and Wickard are striking,” Justice John Paul Stevens wrote for five members of the court, including Justice Kennedy. “Here, too, Congress had a rational basis for concluding that leaving home-consumed marijuana outside federal control would similarly affect price and market conditions.” Justice Scalia wrote a separate concurrence, also citing Wickard v. Filburn. “Congress may regulate even noneconomic local activity if that regulation is a necessary part of a more general regulation of interstate commerce,” he wrote, in a passage that the Obama administration quoted prominently in a recent brief in the health care case. Supporters of the health care law say the Raich decision shows that even completely local and noncommercial conduct may be addressed by the federal government as part of comprehensive economic regulation. Opponents counter that marijuana, like wheat, is a tangible commodity that is bought and sold, while a lack of insurance is not an economic activity. The administration is probably assured of the votes of the court’s four more liberal members, and it needs one more to win the case. How Justices Kennedy and Scalia think about wheat, marijuana, health insurance and Roscoe Filburn may make all the difference.