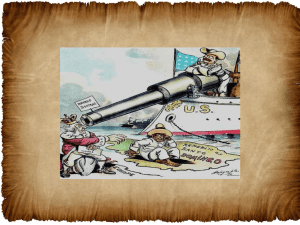

The Monroe Doctrine: Origin and Early American Foreign Policy

advertisement