Settlor's reserved powers and trustee's limited liability

advertisement

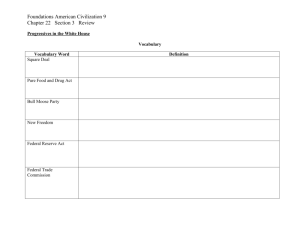

Trusts and Foundations Settlor’s reserved powers and trustee’s limited liability – are private foundations the best of all worlds? By Paolo Panico, Private Trustees SA, Luxembourg and Geneva, Switzerland ince Jersey and the Seychelles joined the league in 2009, seven common law or mixed jurisdictions have added ‘private foundations’ to their range of wealth management solutions. The first path-breaking exercise was attempted with the St Kitts Foundations Act 2003, followed by The Bahamas Foundations Act 2004, the Nevis Multiform Foundations Ordinance 2004 and, in due course, the Antigua and Barbuda International Foundations Act 2007, the Anguilla Foundation Act 2008 as well as, eventually, the Foundations (Jersey) Law 2009 and the Seychelles Foundations Act 2009. These private foundations are creatures of statute, shaped according to the corresponding civil law institutions that, for private purposes, were first epitomised in the Liechtenstein Law of Persons and Companies (Personen- und Gesellschaftsrecht, PGR). They are quite different in nature from the corporate vehicle that has traditionally performed the corresponding functions in common law jurisdictions, i.e. the company limited by guarantee, a detailed regulation of which can be dated back to the English Companies Act 1862. Guarantee companies and hybrid companies featuring guarantee members and shareholders exist under the laws of most common law jurisdictions that follow the English (as opposed to the US) legal model, ranging from the UK and the Republic of Ireland to, most notably, the Isle of Man, Gibraltar, the Cayman Islands, The Bahamas, the British Virgin Islands and the Channel Islands. As a result, both variants of ‘private foundations’ exist in some jurisdictions, such as Jersey and The Bahamas. The common feature they share, and that S OI 206 • May 2010 constitutes the primary structural difference between foundations and trusts, is legal personality. Indeed, the very notion of ‘juristic’ or ‘legal personality’, which is the essential characteristic of corporate entities, was originally thought up in respect of foundations. It was in the 13th century that Sinibaldo de’ Fieschi, a commentator to the Roman civil code who became pope under the name of Innocent IV, suggested that a monastery “should be deemed to be a person” (fingatur una persona). This legal fiction allowed monks to accept and to hold property in the name of the monastery without offending their vows of poverty. Foundations were thus the first institutions to be recognised as separate corporate entities, to the extent that they were established for charitable purposes (piae causae), as they still are under the laws of most continental European jurisdictions. In England the same function was performed by charitable trusts and there are speculations about the common origin of the two institutions. Some points of contact exist also with waqfs, the corresponding Islamic devices for the appropriation of assets to charitable ends. It was not until 1926, with their statutory recognition under § 552 of the Liechtenstein PGR, that foundations (Stifungen) could be incorporated for family or private purposes. Private foundations gained an increased international popularity as estate planning and asset protection tools as a result of the Panamanian law of 12 June 1995 n 5 on ‘private interest foundations’ (fundaciones de interés privado). Most recently, the Liechtenstein model legislation underwent a thorough overhaul that came into force as of 1 April 2009. Foundations are radically different from trusts from a structural point of view. The former are corporate entities, or ‘juristic persons’, while the latter are legal relationships between trustees and beneficiaries. On the other hand, from a functional point of view, private foundations can be created for the same asset protection or estate planning purposes for which property may be settled on a private express trust. An intriguing question is then why a number of common law jurisdictions, some of which feature highly sophisticated pieces of trust legislation, have felt the need to fit an essentially civilian statutory creature into their legal systems. Two aspects stand out, in respect of which private foundations appear to offer an ingenious solution to some shortcomings of the traditional English trust. They are: (i) the settlor’s ability to retain powers without jeopardising the validity of a trust and (ii) the unlimited personal liability of trustees. To be sure, the benchmark for this discussion is the trust according to English equitable principles. Of course, trust law varies – and in some respects quite significantly – across the multitude of trust jurisdictions around the world. Private foundations legislation is less diversified, yet different approaches are available under the laws of the individual jurisdictions. Accordingly, some degree of generalisation is inevitable. Founder’s – as opposed to settlor’s - reserved powers Foundations come into existence as a result of some formal incorporation process that usually involves registration with a competent registrar. As a result, such registrar may issue, on request, a certificate of registration or of good standing similar to the corresponding 11 Trusts and Foundations 12 documents issued in respect of international business companies and evidencing the existence and good standing of the foundation. As a result of such process, foundations acquire ‘legal personality’ and exist as separate legal entities. By an extension of the authority in Salmon v Salmon & Co Ltd1, the assets transferred to a foundation are separate from those of the founder. Some statutes spell out this principle in unequivocal terms. A widely followed example is section 67 of the St Kitts Foundations Act 2003: Assets irrevocably transferred to a foundation shall: (a) become the assets of the foundation; (b) cease to be the assets of the founder; and (c) not be the assets of a beneficiary unless and until distributed to such beneficiary. It is generally submitted that a consequence of the ‘incorporated’ nature of foundations is the founder’s ability to retain a potentially wide range of dispositive as well as administrative powers. As a result of the House of Lords decision in Salmon, the circumstance that the same person is the main shareholder and the sole director of a company does not undermine the very existence of such company as a separate legal entity. The same principle should apply to foundations. Indeed, some statutes expressly provide for the ‘charter’ or ‘articles’ of a foundation - ie the confidential document containing a detailed regulation of its functioning – to include provisions for the reservation of rights and powers to the founder2. Section 27 of the Seychelles Foundations Act 2009 contains a detailed list of the items that the founder may direct or approve: (a) investment activities of the foundation; (b) amendment of the charter or regulations; (c) appointment or removal of a councillor; (d) appointment or removal of any supervisory person; (e) rights, entitlements and restrictions of a beneficiary; (f) addition or exclusion of a beneficiary; (g) proposed continuation of the foundation as a foundation registered or otherwise established under the written laws of a jurisdiction other than Seychelles; (h) dissolution of the foundation. Section 7(2) of the Anguilla Foundations Act 2008 provides for the founder’s default power of revocation or amendment of the declaration of establishment of a foundation. In addition to any statutory powers provided for under the relevant legislation, the founder may exercise a significant influence on his foundation if he acts as ‘guardian’; a supervisory office similar to that of a trust protector. The corresponding situation of trust settlors is quite different. With the exception of a limited (yet increasing) number of offshore jurisdictions expressly admitting ‘reserved powers trusts’3, a settlor retaining any combination of the powers above would seriously undermine the very existence of the trust and cause it to fail as ‘sham’. The Cayman Islands Court of Appeal, with its unreported judgment in Tasarruf Meduati Sigorta Fonu v Merrill Lynch Bank and Trust Company (Cayman) Limited of 9 September 2009, provided an important confirmation that ‘reserved powers’ legislation is upheld in its home jurisdictions. However, such arrangements are quite likely to be disregarded in any jurisdictions practising and recognising trusts according to the traditional equitable model. For the avoidance of doubt, the Jersey customary rule donner et retenir ne vaut, which was at the basis of a widely discussed (and probably overemphasised) sham doctrine after the ‘Rahman case’4, is expressly repealed under Article 33 of the Foundations (Jersey) Law 2009 in the same way as it was ruled out under the 2006 amendment of the trusts law5. This is perhaps the most energetically advertised feature of private foundations. They are allegedly fit for clients with a civil law background, who would be unlikely to really grasp the trust concept, and, more generally, they appear to accommodate every settlor’s unuttered dream to retain substantial control over ‘his’ trust property. This proposition is largely untested to the extent that no case law is available for the time being. On the other hand, some precedents on ‘sham companies’ have existed for nearly a century. James Wadham’s article in an earlier issue of this journal makes a salutary reading to this effect6. For instance, in Gilford Motor Co Ltd v Horne7 a company purportedly created by the defendant’s wife was held to be a ‘cloak or sham’ to breach his contractual obligations to the plaintiff. In Trebanog Working Men’s Club ad Institute Ltd v Macdonald8, a club was held to act as trustee for its members. An elaborate discussion of the ‘sham company’ notion was rehearsed (albeit unsuccessfully) by the Australian Federal Court of Appeal in Re Sharrment Pty Ltd9. Furthermore, tax authorities may disregard the legal nature of foundations for their own purposes and classify them as trusts or as companies so to maximise revenue. A recent example is the IRS Chief Counsel Advice Memorandum AM2009-12 of 7 October 2009, attempting to classify Liechtenstein Stiftungen and Anstalten. More generally, the application of the OECD ‘effective management and control’ test may be relevant for founder-driven private foundations, if not to deny their existence as legal entities, at least to establish their residence for income tax purposes. To the extent that the founder is unlikely to be resident in the same offshore jurisdiction of incorporation of the foundation, this point should be carefully considered in any wise planning exercise. Councillors’ – as opposed to trustees’ – contractual liability The ‘reserved powers’ feature discussed above is mostly meant to appeal to would-be founders or settlors, i.e. ‘the clients’. On the other hand, another aspect of private foundations, equally deriving from their ‘corporate’ nature’, may be particularly significant for service providers deciding to act as foundation ‘councillors’ rather than as trustees. To the extent that trusts are not separate legal entities, they cannot trade, hold property, sue or be sued in their own right. Trustees are the legal subjects that do all these things. As a result, under the traditional English model, trustees are prima facie personally answerable for the liabilities they incur in the exercise of their fiduciary duties. In turn, to the extent that they did not commit a breach of trust, they have a right of indemnity to recoup their expenses out of the trust fund. A clear statement of this principle can be found in Vacuum Oil Company Pty Ltd v Wiltshire, an Australian High Court decision relating to the widespread Antipodean practice of ‘trading trusts’10: In respect of debts incurred [by the trustee] in so carrying on the business he is personally liable to the trading creditors – the debts are his debts. A Victorian authority for this inflexible principle was the House of Lords decision in Muir v City of Glasgow Bank11, where the circumstance that certain trustees were entered as ‘trust disponees’ for the named beneficiaries in the shareholders register of a bank did not relieve them from the unlimited liability implied under the bank articles (the bank was organised on a copartnership basis). More than a century later, in Marston Thompson & Evershed plc v Bend12, the trustees of a rugby club entered into a loan agreement expressly describing them as trustees, nevertheless they were held personally liable to repay the debt as the club property was not sufficient to that effect. Even a practising offshoreinvestment.com OI 206 • May 2010 means of provisions purporting to limit the personal accountability of trustees for properly incurred liabilities. An eloquent example is article 32(1)(a) of the Trusts (Jersey) Law 1984, as amended by the Trusts (Amendment No. 4) (Jersey) Law 2006: Where a trustee is a party to any transaction or matter affecting the trust, if the other party knows that the trustee is acting as trustee, any claim by the other party shall be against the trustee as trustee and shall extend only to the trust property. These statutory solutions stretch the notion of trusts and extend to them some of the features of corporate entities. An alternative approach is indeed to opt for a separate ‘juristic person’ performing the same functions of a trust, as it is the case of private foundations. Given their civil law origin, private foundations derive their constitutive principles from contract law, as opposed to equity. As a result, the duties of the officers in charge of their administration, who are usually described as ‘councillors’ or ‘council members’, are contractual – not fiduciary – in nature. A clear statement to this effect can be found in section 11(1) of the Bahamian Foundations Act 2004, making it clear that ‘[t]he duties and responsibilities of an officer shall be primarily administrative, rather than fiduciary in nature’. Article 25(1)(b) of the Foundations (Jersey) Law 2009 goes a step further and specifies that: ‘a beneficiary under a foundation is not owed by the foundation or by a person appointed under the regulations of the foundation a duty that is or is analogous to a fiduciary duty’. As a result of the contractual nature of their duties, and to the extent that they abide to the statutory duty of care imposed on them under the relevant legislation, private foundation councillors are not personally liable for the obligations they undertake in the exercise of their function. To this purpose, section 33(1) of the Bahamian Foundations Act 2004 provides that: No officer of a foundation shall be personally responsible for any liability of a foundation unless such liability shall have been incurred as a result of his own gross negligence, wilful default or misconduct, fraud or dishonesty. Under the same token, section 23 of the Anguillan Foundation Act 2008 provides for a limitation of liability in respect of the exercise of the council members’ powers with the prior authorisation of the ‘guardian’. Let us go back to trusts by way of conclusion. The personal creditors of trustees are barred from attaching the trust property. This is a quintessential principle of trust law and as such it was incorporated into the Hague Convention of 1 July 1985 on the Law Applicable to Trusts and on their Recognition, under which trusts have made their way into a number of civil law jurisdictions. The opposite principle does not apply, or at least not in all trust jurisdictions. In other words, trustees are personally liable to the trust creditors under the laws of England and of many Commonwealth jurisdictions closely following the English approach. This is a source of potential nuisance to trustees, beneficiaries and any third parties dealing with trusts. Some statutory solutions following the US model have the side effect of transforming the trust into something similar to a corporation. Private foundations can be an alternative solution, relying on the features of ‘legal personality’ and effectively limiting the liability of service providers. Trusts and Foundations lawyer could end up overlooking this principle, as it happened in AMP v MacAlister Todd13, a case recently heard by the Supreme Court of New Zealand, where a solicitor trustee failed to realise that the liability for the Goods and Services Tax payable on the sale of some trust property is a personal liability of trustees. However deeply rooted in the English legal tradition – and perhaps in the very essence of the trust as a legal institution – this revered principle gives rise to a twofold set of drawbacks that were identified by the English Trust Law Committee in its 1999 Report on ‘Rights of Creditors against Trustees and Trust Funds’. On the one hand, the potential hurdles to the operation of the trustee indemnity may impair the trust creditors’ ability to have their claims satisfied out of the trust fund14. On the other hand, the personal liability of trustees may have an adverse impact on their ability to effectively administer their trusts or it may increase their costs of risk management and professional insurance, which in turn means higher trusteeship fees to the detriment of the beneficiaries. Personal exposure to unlimited liability may have induced effective selfdiscipline for the individuals acting as trustees in Victorian England, yet it is likely to be far less relevant at a time when the trust business is mostly performed by regulated professionals and financial intermediaries. The modern US approach, as expressed in uniform state law, has traditionally differed from the English one. For instance, section 7-306(a) of the Uniform Probate Code contains a statement to the effect that ‘a trustee is not personally liable on contracts properly entered into in his fiduciary capacity in the course of administration of the trust unless he fails to reveal his representative capacity and identify the trust estate in the contract’. An equivalent statement can be found in the Uniform Trust Code15. The notion of a trust as a separate legal entity is well grounded in the US practice and it dates back to the early 20th century, when the ‘Massachusetts trust’ used to function as a holding company. A significant development of this concept is the Delaware ‘business trust’, renamed as ‘statutory trust’ as of 1 September 2002, that is expressly described as ‘a separate legal entity’16, as well as the Uniform Statutory Trust Entity Act, the latest draft of which was approved by the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws at their July 2009 meeting in Santa Fe, New Mexico. This issue is addressed in the trust laws of many offshore jurisdictions by END NOTES: 1. [1897] AC 22. 2. St Kitts, Foundations Act 2003, s 61(2)(a); Bahamas, Foundations Act 2004, s 6(2)(a); Foundations (Jersey) Law 2009, Art 18(1). 3. Nevis, International Exempt Trust Ordinance 1994, s 47; Cook Islands, International Trusts Act 1984, s 13C; Cayman Islands, Trusts Law (2007 Revision), ss 13 – 15; Bahamas, Trustee Act 1998, s 3; Trusts (Jersey) Law 1984, Art 9A; Trusts (Guernsey) Law 2007, s 15. 4. Adel Rahman v Chase Bank (CI) Trust Company Limited [1991] JLR 103. 5. Trusts (Jersey) Law 1984, Art 9(5), inserted by the Trusts (Amendment No. 4) (Jersey) Law 2006. 6. J.A.F. Wadham, ‘First the sham trust, now for the sham company’, Offshore Investment, December/ January 2003, p 40. 7. [1933] Ch 935. 8. [1940] 1 KB 576. 9. (1988) 82 ALR 530. 10. (1945) 72 CLR 319, 324. 11. (1879) 4 App Cas 337. 12. (1997) Law Society Gazette 94/39, 15 October 1997. 13. [2007] 1 NZLR 485. 14. A coverage of this issue is outside the scope of this article but the readers who will bear with a self-quotation may find a detailed discussion at chapter 6 of P. Panico, International Trust Laws, Oxford University Press, 2010. 15. Uniform Trust Code, § 1010. 16. Delaware Code, Title 12, § 3801. “Foundations and Trusts – Some Thoughts” May 2009, Issue 196 13