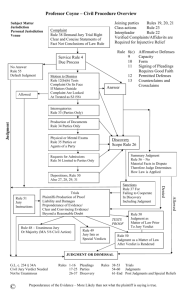

Line-up of the Justices in Michael H. v. Gerald D. Law 300 // Prof

advertisement

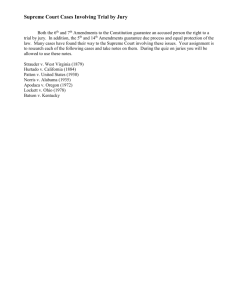

Line-up of the Justices in Michael H. v. Gerald D. Law 300 // Prof. Garet // Spring, 2015 5 votes to affirm the judgment below: Scalia, Rehnquist, O’Connor, Kennedy (the plurality) plus Stevens (concurring in the judgment). 4 votes to reverse the judgment below: Brennan, Marshall, Blackmun (the Brennan dissent) plus White (whose separate dissent, also joined by Brennan, is omitted from our PR excerpt). Compare the line-up of the Justices in Smith v. United States:1 6 vote majority opinion (O’Connor, White, Kennedy, Thomas, Blackmun, Rehnquist) holding that trading a firearm for drugs counts as using a firearm within the meaning of the sentence-enhancement statute. 3 vote dissenting opinion (Scalia, Stevens, Souter) would have held that trading a firearm for drugs does not count as using a firearm within the meaning of the sentenceenhancement statute. PR p. 169: “Justice Scalia announced the judgment of the Court and delivered an opinion, in which the Chief Justice (Rehnquist) joins, and in all but footnote 6 of which Justice O’Connor and Justice Kennedy join.” “Justice Scalia announced the judgment of the Court” – The “judgment of the Court” is its disposition of the appeal. Here, the disposition of the appeal was affirmance of the judgment of the California Court of Appeals, below, upholding the state statute against constitutional challenges. There were five votes (a majority) for affirmance: the four who joined the plurality opinion (Scalia, Rehnquist, O’Connor, Kennedy) plus Stevens (whose opinion concurring in the judgment is omitted from our PR excerpt). Scalia’s four-vote opinion is called a “plurality” opinion. (Brennan’s dissenting opinion describes Scalia’s opinion as a “plurality” at PR p. 174 et seq.) A plurality opinion lacks the precedential force of a majority opinion, in the sense: no holding attracted five or more votes. Lawyers and judges count the votes carefully when reading Supreme Court opinions and when making predictions about how the Court might rule in future cases. Thus lawyers and judges reading the opinions in Michael H. v. Gerald D. noticed that there were only two votes (Scalia and Rehnquist) in support of the level-of-generality stance asserted in the plurality opinion’s footnote 6. (For the text of footnote 6, see PR pp.180-181.) Between 1989 (Michael H) and 1993 (Smith), Souter took Brennan’s seat on the Court and Thomas took Marshall’s. 1 Burdens and presumptions (Schauer, chapter 12) Schauer’s main claim in this chapter: law’s commitments to formality and generality are made in full awareness that adhering to formality and generality can mean not making the best decision in each case. Law says: let us make mistakes, but let us (to the extent possible) make mistakes of the right kind. Standards of proof, Schauer pp. 220-222. Beyond a reasonable doubt; clear and convincing evidence; preponderance of the evidence. 1. Which standard of proof will the judge presiding at trial instruct the jury to apply when the jury deliberates about whether Mr. Smith is guilty of the drug trafficking offense with which he is charge? 2. Which standard of proof will the judge presiding at trial instruct the jury to apply when the jury deliberates about whether the defendant bottling company in Crigger (mouse in Coca Cola bottle) failed to take reasonable precautions in bottling and inspecting the Coke? Burdens of persuasion and production, Schauer p. 223. 3. Macpherson has sued Buick Motors, seeking a recovery from defendant for injuries sustained when the wheel fell off the car and the car crashed. To which party – plaintiff or defendant – does the law assign the burdens of persuasion and production? (E.g., does plaintiff or defendant have the burden of persuasion on the issue of breach of the duty of care, that is, failure to take reasonable precautions?) 4. In Vance, the Supreme Court clarified the criteria for “supervisor” for Title VII purposes, applied those criteria to the facts as found below, and determined that the Ball State University employees who had allegedly subjected Maetta Vance to racial taunting were mere co-workers rather than Ms.Vance’s supervisors. If Ms. Vance continues her Title VII suit against Ball State, which party will bear the burden of persuasion on the question of whether Ball State negligently managed those co-workers or negligently failed to follow up on Ms.Vance’s complaints about the conduct of these co-workers? Rebuttable and irrebuttable presumptions, Schauer pp. 224-229. See Michael H. v. Gerald D. Deference. Deferential (“clear error”) v. non-deferential (de novo) standards of appellate review. Standards of review in constitutional law. Relation between standards of review and presumptions. Schauer, pp. 230-233. 5. In the Mashpee case, the trial court instructed the jury on the criteria for “Indian tribe,” and the jury found that the Mashpee plaintiffs did not satisfy those criteria. When plaintiffs appeal the judge’s jury instructions, should the appellate court review those instructions deferentially or non-deferentially (de novo)? 6. Should the appellate court review the jury’s finding (that the Mashpee plaintiffs did not satisfy the criteria for “Indian tribe”) deferentially or non-deferentially (de novo)?