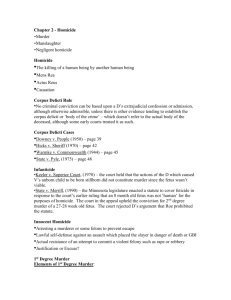

reconsidering the felony murder rule in light of

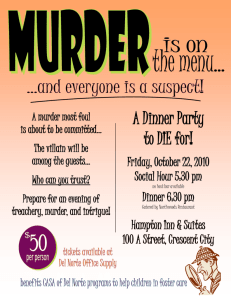

advertisement