It's a Bird, it's a Plane, it's Felony Murder

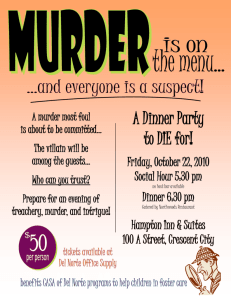

advertisement

Volume 152, No. 157 11, August, 2006 It's a Bird, it's a Plane, it's Felony Murder Last month the Illinois Supreme Court decided a new felony murder case, People v Lavelle Hudson, No. 100033 (July 5). Four justices found that the non-Illinois Pattern Jury Instruction on causation was ''adequate,'' but offered in dictum an alternative instruction. Two justices found that the non-IPI instruction was erroneous, but found the error harmless. One justice dissented. Ready for my analysis? Forget it. To paraphrase the late Justice Harry Blackmun, ''From this day forward, I no longer shall tinker with the machinery of felony murder.'' See Callins v. Collins, 510 U.S. 1141, 1145 (1994) (Blackmun, J., dissenting from denial of certiorari). Analyzing felony murder with traditional legal tools only perpetuates the myth that it is a real legal doctrine. OK, so what's wrong with felony murder? The Illinois Criminal Code provides that a person is guilty of first-degree murder if in performing the acts that cause the death ''he is attempting or committing a forcible felony other than second degree murder.'' 720 ILCS 5/9-1(a) (3). Illinois courts have long held that under felony murder, ''It is immaterial whether the killing in such a case is intentional or accidental, or is committed by a confederate without the connivance of the defendant or even by a third person trying to prevent the commission of the felony.'' People v. Hudson, slip op. at 6, quoting 720 ILCS Ann. 5/9-1, Committee Comments-1961, at 15 (Smith-Hurd 2002), citing People v. Payne, 359 Ill. 246 (1935) (emphasis added). See that word ''accidental''? You mean you can be guilty of first-degree murder based on an accidental killing? Sure. In the words of the non-IPI instruction found adequate in Hudson, a forcible felon is guilty of first-degree murder as long as the accidental killing was the result of a chain of events set in motion by the felon. The only mental state needed is intent to commit the felony. No mental state is needed vis a vis the killing. Thus, what we euphemistically call ''felony murder'' is in reality ''absolute liability murder based on the commission of a forcible felony.'' You mean you can be guilty of first-degree murder based on absolute liability? You bet. Again, the only mental state required is intent to commit a forcible felony. The State has no burden of proving that defendant possessed any mental state vis a vis the death that occurred. In fact, Illinois courts have held — presumably with a straight face — that even a Class 3 felony such as involuntary manslaughter requires proof of a more culpable mental state than felony murder. People v. Schickel, 347 Ill.App.3d 889, 895 (1st Dist. 2004); People v. Williams, 315 Ill.App.3d 22, 32-33 (1st Dist. 2000). No, I am not making this up. If you do not believe me, read the cases yourself. If the Mad Hatter wrote this stuff it would be funny; but, unfortunately, this is the state of Illinois criminal law in the 21st century. Consider this example. Jones breaks into a house at night and is guilty of residential burglary. When he gets inside, he lights a match in order to see in the dark. He then accidentally drops the match and the house burns down. Is Jones guilty of arson? Of course not. Arson requires that a person ''knowingly'' damage real property. 720 ILCS 5/20-1 (a). Dropping the match was an accident. You need a concurrence of bad mental state and bad voluntary act to be guilty of a crime. That fact that he is a burglar does not automatically also make him guilty of arson. Now let's add a fact. What if the accidental fire caused the death of the owner sleeping in her bedroom? Jones was committing the ''forcible felony'' of residential burglary. 720 ILCS 5/2-8. Jones set in motion the chain of events that caused the accidental death of the owner. Looks like felony murder to me. On the same facts, while an Illinois court would sanctimoniously announce that Jones could never be guilty of the Class 2 felony of arson, it would have no trouble finding him guilty of first-degree murder based on the felony murder doctrine. So how did we get into this felony murder mess? It is generally conceded that the so-called ''felony murder rule'' is based on nothing more than a mistake made by English legal commentators several centuries ago. Some point to Lord Coke's treatise in 1644 as the possible source of this faux ''rule.'' While it is true that his treatise characterized a killing that occurred during the commission of an unlawful act as ''felonious,'' the cases he cited provided no direct support for anything like a ''felony murder rule.'' Instead, when Coke described an unintended killing during an unlawful act as ''felonious,'' what he probably intended to say was that such a killing would be punished as manslaughter, rather than murder. Nevertheless, relying on this type of error, English judges created the ''felony murder rule'' through common law. (For background on the strange history of the felony murder doctrine, see James J. Tomkovicz, The Endurance of the Felony Murder Rule, 51 Washington and Lee Law Review 1429 (1994) and Nelson E. Roth and Scott E. Sundby, The Felony Murder Rule: A Doctrine at Constitutional Crossroads, 70 Cornell Law Review 446 (1985).) England, to its credit, eventually admitted this so-called ''rule'' was nonsense. Parliament abolished the felony murder doctrine in 1957. See Homicide Act of 1957, 5 & 6 Eliz. 2. Nevertheless, it continues to thrive in America. So what can I tell you about the new Hudson case? Let me ask you this. When you were a kid, did you ever read ''Metropolis Mailbag'' in the Superman comic books? A typical question would be something like ''Dear Editor: In the May 1959 issue you ran a story that showed Superman carrying a plane that had engine failure. I think I saw a drop of sweat on his face on page 16. Does this mean there are limits to his strength, other than those caused by exposure to kryptonite? Just Wondering, J.L., Keokuk, Iowa.'' The editors would then proceed to give elaborate answers trying to explain the drop of sweat. Sometimes both the question and answer were decidedly tongue-in-cheek. But sometimes the question and answer took on the surreal quality of trying to create an alternative universe out of pure fiction. The Illinois Supreme Court's felony murder decisions have this same quality. They try to create a plausible world out of the implausible. They attempt to justify a theory of murder that has a mental state less culpable than that of involuntary manslaughter, a Class 3 felony. Like Gertrude Stein's Oakland, there is no ''there'' there. The Supreme Court refuses to confront the fact that felony murder allows a court to convict a person of first-degree murder without any showing of fault, i.e., mens rea, with respect to the death of the victim. It refuses to discuss the serious problem of a murder theory predicated on absolute liability. Hudson has three separate opinions that go on and on about ''cause in fact'' and ''legal cause'' and ''proximate cause'' and ''foreseeability'' without once confronting the real problem with felony murder: you are convicting a person of murder based on absolute liability. See Sanford H. Kadish and Stephen J. Schulhofer, Criminal Law and Its Processes (7th ed. 2001), p. 451. It is ironic that this same court has regularly engaged in pages and pages of judicial hand wringing while trying to decide if some nickel-and-dime offense can be committed with no mental state. See, e.g., People v. O'Brien, 197 Ill.2d 88 (2001) (collecting cases). Yet when faced with ''absolute liability murder based on commission of a forcible felony,'' the court buries its head in the sand. And, sadly, the court even fails to understand why causation in felony murder is so problematic. The answer? It goes back to felony murder being an absolute liability offense that requires no mens rea regarding the death. Because this idea violates our most basic ideas of justice, the court unconsciously tries to make ''foreseeability'' do double duty both for mens rea and causation. The result? Conflating mens rea and causation creates the chaos of decisions such as Hudson. Am I trying to exculpate all forcible felons who cause deaths? Of course not. If the killings were committed intentionally or knowingly, the defendants can be convicted under traditional Illinois theories of first-degree murder. 720 ILCS 5/9-1 (a) (1) and (a) (2). Also, the Model Penal Code proposed an alternative to felony murder many years ago. First, it abolished felony murder. But it then created a new theory of murder defined as a killing that is the result of an act ''committed recklessly under circumstances manifesting extreme indifference to the value of human life.'' The Code goes on to provide that, if the defendant is in the process of committing any one of a list of serious felonies when the death occurred, this fact creates a rebuttable presumption that he acted with the indifference and recklessness needed for a murder conviction under the new theory. American Law Institute Model Penal Code Official Draft, 1962, Section 210.2 (1) (b). The Model Penal Code thus allows for the possibility that deaths during forcible felonies may indeed be murders. However, it demands that the murder conviction be predicated on a mens rea that has an actual relation to the death. You want to know more about the fine points of felony murder causation discussed by the Illinois Supreme Court in People v. Hudson? Sorry, but you'll have to find out for yourself. From now on, when I see an Illinois decision that discusses felony murder minutiae — while stubbornly refusing even to acknowledge the injustice of a theory that turns first-degree murder into an absolute liability offense — the opinion goes straight into the ol' Metropolis Mailbag.