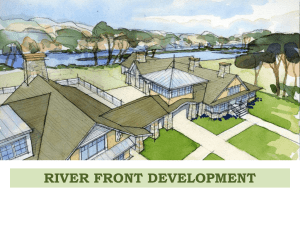

waterfront redevelopment at south street seaport

advertisement