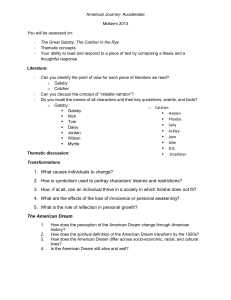

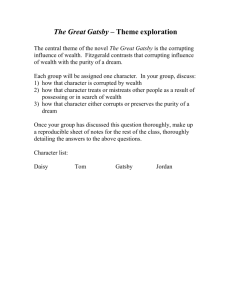

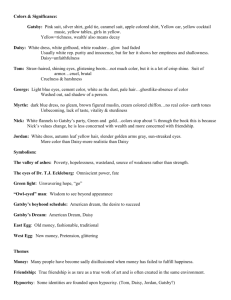

Great American Dreams

advertisement