Enough is Enough - Center for the Advancement of the Steady State

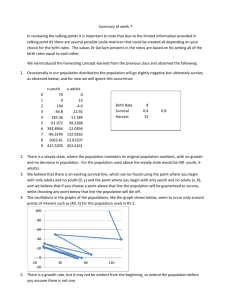

advertisement