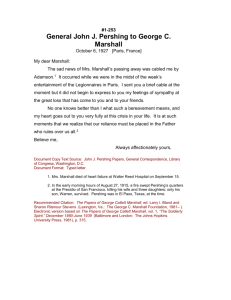

The Marshall Plan 1941-1951 - George C. Marshall Foundation

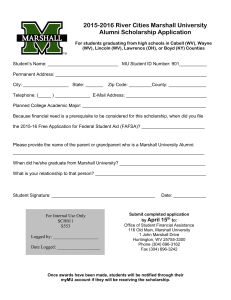

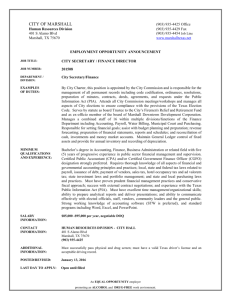

advertisement