Gutsy moves in mice: cellular and molecular dynamics of endoderm

Downloaded from http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on March 6, 2016

rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org

Review

Cite this article: Viotti M, Foley AC,

Hadjantonakis A-K. 2014 Gutsy moves in mice: cellular and molecular dynamics of endoderm morphogenesis.

Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 369 :

20130547.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0547

One contribution of 14 to a Theme Issue

‘From pluripotency to differentiation: laying the foundations for the body pattern in the mouse embryo’.

Subject Areas: cellular biology, developmental biology, genetics, molecular biology, evolution

Keywords: gastrulation, gut morphogenesis, visceral endoderm, definitive endoderm, epithelial-tomesenchymal transition, mesenchymal-toepithelial transition

Author for correspondence:

Anna-Katerina Hadjantonakis e-mail: hadj@mskcc.org

Gutsy moves in mice: cellular and molecular dynamics of endoderm morphogenesis

Manuel Viotti

1

, Ann C. Foley

2

and Anna-Katerina Hadjantonakis

3

1

Genentech Incorporated, South San Francisco, CA 94080, USA

2

Department of Bioengineering, Clemson University, Charleston, SC 29425, USA

3

Developmental Biology Program, Sloan-Kettering Institute, New York, NY 10065, USA

Despite the importance of the gut and its accessory organs, our understanding of early endoderm development is still incomplete. Traditionally, endoderm has been difficult to study because of its small size and relative fragility. However, recent advances in live cell imaging technologies have dramatically expanded our understanding of this tissue, adding a new appreciation for the complex molecular and morphogenetic processes that mediate gut formation. Several spatially and molecularly distinct subpopulations have been shown to exist within the endoderm before the onset of gastrulation. Here, we review findings that have uncovered complex cell movements within the endodermal layer, before and during gastrulation, leading to the conclusion that cells from primitive endoderm contribute descendants directly to gut.

1. Introduction

The endoderm is one of three definitive germ cell layers generated at gastrulation.

Cells descended from the endoderm will constitute the epithelial lining of the respiratory and digestive tracts, as well as the endocrine glands, and auditory and urinary systems. Although a large body of work exists concerning the specification and formation of the endoderm in different model systems, in the mouse, recent studies have called for a rethinking of the cellular dynamics that drive the initial phases of gut endoderm formation. It is now clear that, rather than respecting a strict embryonic–extraembryonic segregation of cell lineages, the gut endoderm is composed of cells derived from both definitive endoderm

(DE) and so-called extraembryonic endoderm, and that these two cell populations are coordinately integrated into a single tissue, the gut endoderm, through a process of dispersion and intercalation.

2. A panoply of endoderm

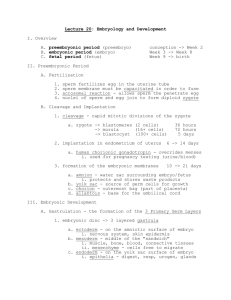

At the time of implantation into the maternal uterus (at around embryonic day (E)

4.5), the late blastocyst stage mouse embryo comprises three tissue lineages: the pluripotent epiblast and two extraembryonic lineages, the primitive endoderm

(PrE; figure 1 and table 1) and the trophectoderm. Shortly after implantation

(E4.5–E5.0), the embryo elongates to form a radially symmetric egg cylinder,

which concomitantly cavitates at its centre (reviewed in this issue [1]). At this

point, the embryo comprises a bilaminar cup-shaped epithelium. The outer layer consists of the PrE-derived visceral endoderm (VE) that encapsulates the proximally positioned extraembryonic ectoderm (ExE), and the distally positioned, pluripotent epiblast that will go on to form the embryo proper as well

as some extraembryonic mesoderm (figure 1).

As is the case in several vertebrates, in the mouse there are two recognized sources of endoderm tissue, one arising from the PrE and the other from the plur-

ipotent epiblast [2,3]. Until recently, the canonical thinking dictated that the PrE

gave rise only to extraembryonic lineages such as the parietal endoderm and VE of the early postimplantation conceptus, whereas endodermal cells that ingressed through the streak made up the embryonic endoderm that comprises the gut.

&

2014 The Author(s) Published by the Royal Society. All rights reserved.

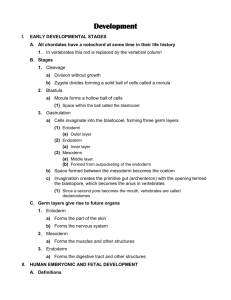

Downloaded from http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on March 6, 2016 morula eight-cell

E2.5

early blastomeres early blastocyst

E3.5

mid blastocyst

E3.75

trophectoderm late blastocyst

E4.5

implantation early postimplantation gastrulation

E5.5

E6.5

time parietal endoderm (PE) primitive endoderm

(PrE) visceral endoderm (VE) inner cell mass

(ICM) definitive endoderm (DE) epiblast mesoderm ectoderm

P

A P

D mesoderm progenitors primitive streak mesoderm progenitors?

DE progenitors?

DE progenitors?

R

A P

L primitive streak

Figure 1.

Schematic depicting early lineage relationships in the mouse embryo. By embryonic day 3.5 (E3.5), the blastula-stage embryo has given rise to the trophectoderm (green) and the inner cell mass (ICM; magenta). The ICM gives rise to both the pluripotent epiblast (red) and primitive endoderm (PrE; blue).

The PrE later differentiates into the both the parietal (PE) and visceral (VE) endoderms (dark and light blue, respectively) and the epiblast gives rise to the three embryonic lineages, definitive endoderm (DE; purple), mesoderm (orange) and ectoderm (red).

At early postimplantation (E5.5–E6.5), the VE epithelium comprises several subpopulations, generally encompassing: the extraembryonic VE (exVE), a cuboidal epithelium overlying the ExE, and the embryonic VE (emVE), a squamous

epithelium overlying the epiblast [4–9]. While exVE and

emVE cells have different morphology and patterning abilities, it is important to note that these names (ex versus em) primarily relate to the position of the VE relative to the conceptus, but that all VE cells stem from the PrE. A further segmentation occurs within the emVE, its most distal cells forming the

distal VE (DVE) at E5.5 [10]. Between E5.5 and E6.5, cells of

the emVE undergo positional rearrangements and become further patterned, resulting in the establishment of the anterior

VE (AVE) [11]. DVE and AVE express specific factors that

are involved in patterning the underlying epiblast along its proximal–distal (P–D) and anterior–posterior (A–P) axes

[2,12–14]. Additional marker-specific subpopulations of VE

cells have been reported, although such regions have typically

not been given names by their position [11,15,16].

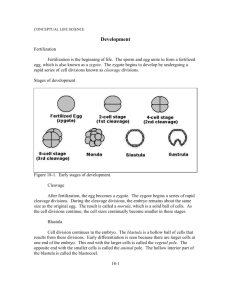

3. The displacement model of gut endoderm formation

About a quarter of a century ago, elegant fate-mapping experiments using single-cell iontophoretic injection of horseradish peroxidase resulted in the first conceptual reconstruction of the cellular dynamics involved in endoderm formation in

mouse embryos [17,18]. In this set of studies, cells of the epi-

blast and VE were individually labelled, embryos incubated for various time periods and then the position of their cellular descendants noted. Derivatives of epiblast cells from the region in the vicinity of the anterior primitive streak (APS) were likely to end up on the embryo’s surface, often in the area of the DE, and at later stages appeared within the gut tube. By contrast, descendants of VE cells overlying the midline, which are referred to as axial VE cells, often appeared in extraembryonic regions of the conceptus. This gave rise to the notion that epiblast cells around the APS ingress (EMT) at the primitive

streak (figure 2), and subsequently egress (MET) to emerge at

the surface inserting into the VE at the distal tip of the embryo. As increasing numbers of cells undergo this process, the newly formed sheet of DE cells would form a contiguous epithelium with the VE, which would gradually and uniformly displace the latter to proximal regions, from where it would exclusively contribute to extraembryonic tissues. Additional, fate-mapping analyses using orthotopic grafting and other cell labelling techniques supported the notion that cells in the posterior epiblast near the APS end up on the embryo’s surface

and give rise to gut endoderm cells [14,19] (figure 2). Few

studies have looked directly at the fate of VE cells, but one in particular appeared to support the displacement model. VE

2

Downloaded from http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on March 6, 2016

Table 1.

Endodermal cell populations of the early mouse embryo.

primitive endoderm parietal endoderm visceral endoderm distal visceral endoderm and anterior visceral endoderm extraembryonic VE embryonic VE definitive endoderm gut endoderm

PrE

PE

VE

DVE and AVE exVE emVE

DE blastula-stage tissue layer, precursor to parietal and visceral endoderm

PrE-derived cell population that lies adjacent to the mural trophectoderm. Fated to contribute to the endoderm layer of the parietal yolk sac as well as the deposition of Reichert’s membrane

PrE-derived epithelial sheet that encapsulates the extraembryonic ectoderm proximally and epiblast distally. Fated to form the endoderm layer of the visceral yolk sac, as well as part of the gut tube two molecularly distinct subdomains of the VE, one located at the distal tip of conceptus (DVE), and the other demarcating the prospective anterior of the conceptus (AVE) subset of VE cells situated in the extraembryonic region of the postimplantation conceptus, overlying the extraembryonic ectoderm. Fated to give rise to the endoderm of the visceral yolk sac subset of VE cells in the embryonic region of the early postimplantation conceptus, overlying the epiblast. Probably fated to give rise to some yolk sac endoderm as well as part of the gut tube epiblast-derived cell population of cells that contributes to the gut endoderm precursor of all endodermal tissues in the adult organism. It is an epithelium composed of emVE- and DE-derived cells

3 cells at the distal tip of the conceptus at E5.5 were labelled with

DiI and examined after 24 h. These labelled cells showed a marked directional movement towards the anterior of the forming embryo, ending up in the AVE. While these cells did not themselves cross over into the extraembryonic region, this finding strongly suggested that cells ‘ahead’ of those labelled must have migrated outside of the embryo proper

[20]. Later, it was shown that VE cells abruptly stop their for-

ward movement once they have reached the embryonic/ extraembryonic border, and thereafter begin to migrate later-

ally [9]. Whether the organization of the VE epithelium

overlying the ExE provides an impenetrable physical barrier, or a repulsive signal, to promote the cessation of anteriorward

AVE migration remains an open question.

In addition to fate-mapping studies, several other observations appeared to support the notion that VE is displaced by the forming DE. Morphological analysis of cells on the embryo’s surface nicely fits in with the displacement model. Initially, heavily vacuolated cuboidal cells, typically associated with VE, surround the entire conceptus, but after gastrulation, cells with this shape are confined to extraembryonic regions while cells on the surface of the embryonic region are squamous, classically associated with

the DE lineage [7]. Analysis of the localization of pan-VE-

markers also fit the displacement model. At first, VE markers such as Ttr, Afp , Sox7 or Hnf4a are present in a layer of cells surrounding the entire conceptus, but when gastrulation is complete, their domain of expression is restricted to proximal

regions [4,21,22]. This supported the notion that the VE is

displaced proximally as a uniform cellular sheet.

4. Proposing cell dispersal as a morphogenetic mechanism for gut endoderm

The displacement model remained in place for nearly two decades until recent advances in live cell imaging techniques allowed, for the first time, direct imaging of cell movements throughout the VE during gastrulation. These studies revealed surprising new details about how the gut endoderm is formed. In particular, generation of the Afp–GFP transgenic mouse strain permitted labelling of the entire VE and this allowed global imaging of the cellular dynamics occurring within the VE layer during gut endoderm mor-

phogenesis [23]. In this strain, green fluorescent protein

(GFP) is expressed under the enhancer/promoter sequence of alpha-fetoprotein ( Afp ).

Afp is a VE-specific marker in early postimplantation embryos, and is also expressed at later stages of development in a series of tissues, including endoderm derivatives. At gastrula stages, all VE cells in

Afp–GFP embryos are labelled with GFP. Additionally, owing to the perdurance of the GFP, immediate descendants of VE cells are labelled as well, even if the transgene is no longer being transcribed. This renders the Afp– GFP strain both a marker for pre-gastrula VE and a short-term cell lineage tracer for VE-derived cells.

Live imaging of Afp–GFP embryos resulted in a surprising

finding [21]. In accordance with the displacement model, upon

gastrulation, one might have expected an initially uniform sheet of GFP-positive cells covering the entire conceptus to be gradually displaced proximally by a new sheet of GFP-negative cells emerging from the distal tip of the embryo. This was not observed. Instead, GFP-negative areas, corresponding approximately to the size of single cells, began appearing within the region of the emVE. Over time, the GFP-negative areas grew in size, diluting the GFP-positive areas initially to cohorts and eventually to single cells. Further experiments suggested that single epiblast-derived cells probably intercalated into the emVE, the descendants of which remained in the embryonic region of the conceptus rather than being displaced to the extraembryonic region. Time-lapse movies revealed that, over time, cells of the emVE epithelium became dispersed to the point of ending up as single cells among a majority of DE cells. This was achieved through widespread DE cell intercalation at VE cell interfaces over a short period of time. Furthermore, time-lapse movies revealed that the progeny of VE cell divisions appeared to move apart, suggesting an intrinsic repulsive mechanism operating between VE descendants, or an underlying differential cell– cell adhesion. These studies also revealed that emVE-derived cells could later be found in the gut tube, and were present until at least the 15 somite stage, raising the possibility that

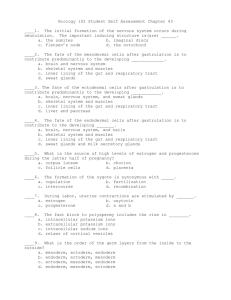

Downloaded from http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on March 6, 2016 primitive streak epiblast primitive streak mesoderm epithelial cell

(epiblast) ingression

(EMT) time mesenchymal

(mesoderm) cell partially polarized definitive endoderm progenitor?

mesenchymal

(mesoderm) cell mesenchymal

(mesoderm) cell egression

(MET) epithelial cell

(visceral endoderm) epithelial cell

(definitive endoderm) epithelial cell

(visceral endoderm) embryo surface visceral endoderm (VE) definitive endoderm (DE) mesoderm gut endoderm

Figure 2.

Relating the cellular dynamics of gut endoderm morphogenesis to epithelial – mesenchymal transitions. During gut endoderm formation, cells undergo both epithelial-to-mesenchymal (EMT) and mesenchymal-to-epithelial (MET) transitions in rapid succession. At the primitive streak, DE progenitors ( purple) exit the epithelial pluripotent epiblast (blue) and enter the mesenchymal wings through the process of ingression. The ‘wings’ consist of DE precursors and mesoderm

(orange). Once they have reached their final position, DE cells egress from the mesenchymal wings into the newly formed endodermal epithelium that is composed of DE cells and visceral endoderm cells (VE; blue).

cells from an extraembryonic lineage persist within the gut of the fetus, and possibly even the adult. These observations were confirmed using other fluorescent protein reporter lines, as well as using genetic fate mapping with a pan-VE Ttr-Cre

line and lacZ- and GFP-based Cre reporters [24].

These data suggest a new model that can account for both these new findings as well as previous fate-mapping and gene expression data. In what we refer to as the cell dispersion model, the epiblast-derived DE does not displace the emVE as a sheet. Instead, the DE initially migrates

4

Downloaded from http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on March 6, 2016 beneath the emVE and gradually causes the emVE to disperse as increasing numbers of DE cells egress into it.

5. A stage-by-stage description of cellular dynamics that drive endoderm formation

(a) Pre-gastrulation and ingression through the primitive streak

Before gastrulation, the emVE encapsulates the epiblast, where the precursors of the DE lineage reside. The anterior part of the emVE epithelium, the AVE, expresses inhibitors of Nodal and

Wnt3, restricting the activity of these genes to posterior regions

[25,26]. In the posterior of the embryo, high levels of Nodal

and Wnt3, in addition to bone morphogenetic protein 4

(BMP4), elicit the formation of the primitive streak, marking

the onset of gastrulation [27]. Posterior epiblast cells become

fated to the mesoderm and DE lineages, ingress through the primitive streak and undergo an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Cells lose epithelial morphology and adopt a mesenchymal shape by breaking down apical–basal cell polarity, cell–cell junctions, as well as constituents of the basement membrane, freeing them to migrate away from the vicinity of the primitive streak. Fibroblast growth factor

(FGF) signalling mutants [28–30] as well as embryos lacking

Snail [31], Eomes [32] or Brachyury [33,34] have cells that

ingress at the primitive streak but cannot correctly migrate away from it, as a result of incomplete EMT. These mutants invariably fail to establish both mesoderm and DE. It is therefore largely accepted that all epiblast cells that will give rise to

DE lineage undergo EMT at the primitive streak.

(b) Migration of definitive endoderm progenitors

The concept that DE emerges at the distal tip of the conceptus resulted from fate-mapping studies that showed that DE pre-

cursors reside near the APS [17 –19]. The primitive streak is a

dynamic structure: it starts out as a small region of cellular ingression in the most posterior part of the epiblast (at the epiblast– ExE border), which then gradually elongates distally and anteriorly until reaching the embryo’s distal tip.

Thus, the position of the APS and fate of cells emanating from it are likely to change over time. Furthermore, DE of the mid- and hindgut is unaffected in Foxh1 and Foxa2

( Hnf3 b ) mutant embryos, both of which fail to specify the

APS [35]. Therefore, while stage-specific fate maps suggest

a fairly localized origin for the DE, in fact these cells might have origins all along the primitive streak.

While live imaging data of fluorescent reporter strains visually demonstrate dispersal of the emVE in lateral regions of the embryo, these data do not capture the cellular dynamics occur-

ring in the midline in real-time [21]. Analysis of sequentially

staged Afp–GFP embryos reveals that emVE cells overlying the midline become displaced anteriorly by epiblast-derived cells fated to form axial mesoderm structures (node and noto-

chord) [21]. Hence, in accordance with a displacement model,

some epiblast-derived cells presumably originating in the APS probably insert directly into the endodermal layer from the distal tip of the conceptus, although reporter-based studies

and earlier fate maps [9,20] suggest that these cells spread

only anteriorly and not laterally. This suggests that the midline emerges by intercalation and VR displacement, whereas the gut endoderm forms through intercalation and dispersal. A key open question pertains the mechanism by which the majority of DE cells enter the gut endoderm.

After ingression at the primitive streak, mesoderm progenitors emerge as a new mesenchymal layer sandwiched between inner epiblast and VE on the embryo’s surface, and are referred to as the wings of mesoderm. This mesenchymal tissue layer migrates from both left and right sides of the primitive streak in a posterior-to-anterior direction, effectively circumnavigating the conceptus, but stopping short of the midline. As a consequence, the most proximal cells in the wings are more advanced in their migration because they emerged from the streak before the more distal cells. A key component of the dispersal model argues that the DE does not migrate into the emVE layer as a sheet, but rather DE cells must co-migrate with mesoderm progenitors in the wings of mesoderm and then intercalate into different regions of the overlying emVE. The intercalation of single DE cells joining the endodermal epithelium from the wing of migrating mesoderm can be defined as an egression, because it is the reciprocal mechanism to ingression, where single cells leave an

Mixl1 mutants argued that at gastrulation DE and mesoderm movements occur independently

Mixl1 mutants do not make DE, and yet mesoderm is capable of migrating. The observation is per se not in disagreement with a dispersal model: if DE cells fail to be specified, they cannot intercalate into the emVE.

One question that arises is whether cells in the migrating wings of mesoderm are bipotential. Experiments in other

organisms [37–39] and mouse cell lines provide evidence

for a mesendodermal population, but the existence of true bipotential cells that can give rise to either mesoderm or

endoderm remains unresolved in the mouse [27,40]. The

early lineage-tracing experiments using single-cell iontophoresis of horseradish peroxidase showed that in some cases a single labelled posterior epiblast cell could result in cells of

both mesoderm and gut endoderm [17,18]. Investigations of

Nodal mutants have provided several insights into this matter.

In vivo , the levels of Nodal signalling regulate the

selective allocation of both mesoderm and endoderm [41].

Mice lacking Nodal or its co-receptor Cripto fail to form a primitive streak and lack both mesoderm and gut endoderm

[42 –44]. Hypomorphic mutants with moderate levels of

Nodal signalling can form some mesoderm and endoderm, whereas lower levels of Nodal signalling result in a loss of

endoderm, but not mesoderm [45]. By contrast, elevated

Nodal signalling caused by loss of the repressor DRAP1 resulted in an expanded primitive streak and production of

excess mesoderm [46]. These findings suggest that the

levels of Nodal signalling play an important role in regulating the selective allocation of mesoderm and endoderm from a common progenitor population. Further support for the existence of a bipotential mesendodermal population comes from studies on the Wnt/ b -catenin pathway. Upon lineage-specific removal of b -catenin, mesoderm-like cells are present in the endoderm layer of mutant embryos

suggesting a transfating of endoderm to mesoderm [47],

and deletion of b -catenin specifically in Sox17-expressing

cells prevents endoderm formation [48]. Nonetheless, based

on marker expression, it has been suggested that DE and mesoderm cell lineages might already be predetermined

before gastrulation [49], though it should be noted that

markers indicate the state, not fate, of cells.

5

If a mesendodermal state indeed exists within the mouse embryo, it is worth considering how it might tie in with a dispersal model of endoderm morphogenesis. Bipotentiality could be restricted to stages immediately after ingression through the primitive streak, or extend on through migration of cells within the wings of mesoderm. While the levels of

Nodal, seen by any individual cell as it passes through the primitive streak, are thought to affect its decision to become mesoderm or DE, we do not know if this is sufficient for the fate choice or if it merely primes cells to one or the other fate, and subsequent environmental cues seal their fate. DE progenitors express endoderm markers just prior to and during

intercalation into the emVE [50]. It is conceivable that a signal

from the emVE instructs adjacent cells to upregulate DE factors.

Only cells in the outer layers of the wings of mesoderm making direct contact with the emVE show expression of DE markers

[50]. Accordingly, ultrastructural examinations of cells in the

wings of mesoderm have revealed that cells adjacent to the emVE are more closely opposed to the basement membrane and more tightly packed than their counterparts that lie closer

to the epiblast [17,51,52], perhaps hinting at an intrinsic hetero-

geneity within the mesoderm, or a subpopulation primed to join the surface endoderm by virtue of its position.

Recently, miR-335 has been implicated in the fate choice

between mesoderm and DE [53]. This intragenic microRNA

is encoded in a mesoderm-specific transcript ( Mest ) and targets the 3 0 UTRs of Sox17 and Foxa2 . Overexpression of miR-335 reduces Sox17 and Foxa2 levels and blocks endoderm differentiation in embryonic stem cells (ESCs) and ESCderived embryos. Conversely, inhibition of miR-335 leads to increased Sox17 and Foxa2 protein accumulation and endo-

derm formation [53]. Yet, when, where and how cells are

instructed to express miR-335 remain open questions.

Mouse ESCs that are treated with Activin A in many respects provide an in vitro model of primitive streak formation and gastrulation-like EMT. Molecular studies in this model suggest that

EMT at gastrulation involves a gene-regulatory feedback loop consisting of Brachyury , Foxa2 and Sox17

Activin A treatment, cells changed their molecular identity, heterogeneously expressing previously silenced Brachyury, Foxa2 and Sox17. Interestingly, Brachyury depletion decreased Sox17 and Foxa2 expression at both transcript and protein levels, suggesting that expression of Brachyury might be a prerequisite for a cell to enter a mesendodermal state. Supporting this mechanism, chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing experiments revealed direct binding of Brachyury to regulatory sequences of

Sox17 and Foxa2. By contrast, overexpression of Sox17 in embryonic bodies resulted in a significant downregulation of

Brachyury, pointing to a negative feedback loop. How the post-EMT heterogeneity of cells is achieved remains an open question. Further studies will be needed to address the question of how cells in the wings of mesoderm sort into mesodermal and

DE populations, and specifically whether a predetermination to one lineage is established at the primitive streak, or if migrating cells become programmed by a positional cue, possibly emanating from the emVE.

6. Egression of definitive endoderm cells into the overlying embryonic visceral endoderm

We have already described how cells fated to contribute to the mesoderm and endoderm enter the mesodermal wings

Downloaded from http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on March 6, 2016 by undergoing EMT at the primitive streak. These cells migrate anteriorly until, shortly thereafter, certain cells in their outer edges begin to express DE makers and intercalate into the emVE. As they leave a mesenchymal population and join an epithelial layer, they undergo a mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET). This rapid EMT– MET cycle raises the question of whether DE cells undergo a complete transition between epithelial and mesenchymal states, or rather whether they might loosen their epithelial characteristics temporarily to migrate, then re-epithelialize during egression. An incomplete or partial EMT and MET have been described in

other contexts [55,56], and further work will be needed to elu-

cidate these details in mouse gut endoderm morphogenesis.

It is not known how Foxa2 and Sox17, the evolutionarily conserved DE transcription factors expressed in egressing

cells [50], control cell egression. Mutants in either one of

these factors exhibit severe reductions of the DE lineage in

the gut endoderm [57 –59]. Evidence is accruing to suggest

that Foxa2, as well as Sox17, regulate factors necessary for epithelialization, such as cell polarity, cell –cell junctions and basement membrane components. An embryo chimaera study focusing on the cell dynamics in the axial midline has reported that Foxa2 mutant cells are capable of inserting into the VE layer, but fails to acquire epithelial polarity or establish new adherens or tight junctions with neighbouring emVE cells, and consequently regress back into deeper

(mesoderm) layers [49]. Accordingly, proteins involved in

cell adhesion during epithelialization have been proposed as direct targets of Foxa2, including Claudin4, Flrt2, Flrt3,

While experimental evidence has yet to connect Sox17 to cell polarity or cell –cell junctions, Sox17 has been shown to bind promoter regions and directly regulates the expression of genes encoding basement membrane factors in some endo-

dermal cell types [61 –63]. Furthermore, a study on mouse

blastocyst stage embryos revealed a requirement for Sox17

in basement membrane formation in the PrE [64].

Another recent study has highlighted the importance of

DE epithelialization as a requisite intermediate step in the differentiation of DE progenitors. The Rho GTPase Rhou controls F-actin distribution and cytoskeletal organization in epithelial cells. Knockdown of Rhou impairs endoderm differ-

entiation in tissue culture as well as in the embryo [65]. It will

be interesting to determine if and how Rhou and other factors regulating cell morphology could function downstream of

Sox17 and/or Foxa2.

Loss of Foxa2 leads to absence of anterior DE (which

would make the foregut) and axial mesoderm [59,66], but for-

mation of mid- and hindgut is largely unaffected [35].

Sox17 mutants appear to display the converse phenotype. Foregut endoderm forms, whereas the regions of the prospective

mid- and hindgut are devoid of DE cells [58]. Furthermore,

the Afp–GFP transgenic reporter reveals the emVE only shows limited dispersal in anterior regions and no dispersal

in mid- and posterior regions [50], suggesting that DE cells

fail to egress in the mid- and posterior regions. Nonetheless, we have also noted that Sox17 mutants properly specify axial

midline structures [50]. Interestingly, Sox17 is localized in the

majority of gut endoderm cells, but is absent from axial midline structures as well as the gut endoderm area around the

anterior intestinal portal [50]. Chimaera studies have shown

that cells lacking Sox17 cannot contribute to mid- or hindgut,

but are capable of contributing to foregut [58]. Conversely,

6

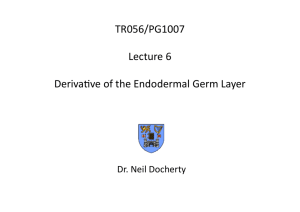

Downloaded from http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on March 6, 2016 anterior anterior yolk sac posterior posterior visceral endoderm (VE) definitive endoderm (DE) midline gut endoderm

Figure 3.

Congregation of VE cells around midline structures. By the end of gut endoderm formation, most of the endodermal epithelium consist of DE cells that have migrated through the streak. Cells from the original visceral endoderm (VE) layer are dispersed as single cells throughout this epithelium except at the midline where VE cells encircle the node and form a continuous line of cells on either side of the midline head process (white and blue cells).

cells lacking Foxa2 can colonize the hindgut, but not the fore-

and midgut [67]. Taking these data into account, one might

envision a mechanism whereby MET of DE cells is controlled by Sox17 in the mid- and posterior areas of the emVE (which will give rise to mid- and hindgut), and by Foxa2 in the anterior (which will give rise to foregut). Additionally,

Foxa2 regulates the epithelialization of cells in the axial

As is the case with almost all endoderm markers, both

Sox17 and Foxa2 are expressed in the extraembryonic and embryonic endoderm lineages, at different stages of

embryo, and absence of Sox17 leads to a disorganized PrE

epithelium in mouse blastocysts [64]. It is therefore tempting

to speculate that Sox17 and Foxa2 are key regulators of endodermal tissue epithelialization throughout development and in adult homeostasis.

emVE cells downregulate cell–cell junctions to accommo-

date egression of DE cells [21]. This response by the emVE

reveals a tight-knit coordination with egressing DE cells, especially taking into account the multifocal egression of DE progenitors into different areas of the emVE. The preferential egression into emVE cells with relaxed cell–cell junctions rather than already egressed DE cells might account for the full dilution of the emVE to single cells by the end of gut endoderm morphogenesis. If a bias to egress into neighbouring emVE cells did not exist, one could expect to find small cohorts of emVE-derived cells in the gut endoderm. The communication signals between cell donor tissue (DE) and the epithelial acceptor tissue (the emVE) remain to be elucidated, and might have implications in other contexts of epithelial reorganization and metastasis.

7. Gut endoderm patterning and gut tube formation

In lateral regions of the gut endoderm, emVE-derived cohorts of cells become diluted until they are single cells surrounded by cells of the DE lineage. By contrast, in the axial midline region, emVE-derived cells remain organized around the

node and notochord (figure 3), suggesting a distinct morpho-

genetic behaviour is likely to have occurred and that the egression mechanism described above may not apply to mid-

line regions [21]. One could envision axial mesoderm

precursors inserting into the distal tip of the embryo, pushing emVE cells aside, which consequently remain organized around the emergent midline and node. As the node expands anteriorly forming the notochord, those axial mesoderm cells could displace a portion of emVE cells anteriorly up to, but not beyond, the embryonic –extraembryonic junction. This would be in concordance with the lineage-tracing and live cell imaging experiments, where pre-gastrulation axial emVE or AVE cells were labelled and the majority of their descendants ended up in anterior regions of the conceptus, but respected the embryonic/extraembryonic border by

remaining in the embryonic region [9,17,18,20,68]. Another

portion of axial emVE cells could be pushed aside, thereby explaining the manner in which emVE cells lie on either side of the notochord in Afp–GFP

By the late bud stage (approx. E7.5), no more DE cells egress onto the surface, and the resulting gut endoderm is a monolayered epithelium. Different regions of the gut endoderm already have distinct molecular characteristics, and have thus started transitioning from a naive epithelium to a patterned tissue. Over time, broad regions of gene expression become refined and result in three distinct domains: foregut, midgut and hindgut. Gut endoderm patterning is, at least in part, directed by environmental cues, for example from the

neighbouring mesoderm [69–72]. Evidence from two

in vitro studies of mouse ESC differentiation into endoderm suggests that the gut endoderm is partly patterned by the

underlying basement membrane [73,74]. In particular, FGF-

induced PI3K/Akt1 signalling was shown to modulate regional extracellular matrix deposition along the A–P axis,

which in turn dictates positional cell-type specification [73].

These findings are substantiated by the observed transfating of mesoderm to endoderm in zebrafish embryos upon

7

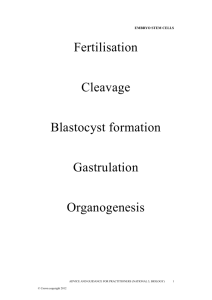

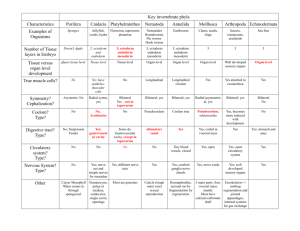

Downloaded from http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on March 6, 2016 blastoc yst gastrulation

(initiation) gastrulation

(endoderm intercalation) mid-gestation

(gut tube formed) time primitive endoderm and descendants

Figure 4.

Distribution of primitive endoderm (PrE) and cellular descendants until midgestation. PrE and derivatives (green) in mouse embryos from E4.5 to E8.75.

Note dispersed VE cells in the distal regions of E7.5 and E8.25 embryos, and presence of VE-derived cells in the gut tube of E8.75 embryos.

Xenopus maternal VegT (T-box)

Xnrs (Nodal) Bix1/4 (Mix)

Eomes Gata4/5/6 mixer (Mix) xSox17 zebrafish mouse

Nodal

Wnt

FGF cyc/sqt (Nodal)

Eomes Gata5/fau Bon & Mezzo (Mix)

Cas (Sox)

Foxa2 Sox17

Eomes Gata4/5/6 Mixl Foxa2 Sox17

Sox17 visceral endoderm nuclei epi mes en ps epi mes en ps epiblast/ectoderm visceral endoderm (VE) definitive endoderm (DE) mesoderm

Sox17 expression time epi endoderm

(VE) epiblast (epi) mesoderm (mes) endoderm (en)

(VE + DE)

Figure 5.

Conservation of a gene-regulatory network driving endoderm specification in vertebrates. A conserved set of molecular players directs endoderm formation across vertebrate phyla. Smad-dependent Nodal signalling activates transcription mediated by conserved members of the Bix/Mix, Sox, Forkhead, Gata and T-box families of transcription factors. Expression of Sox17 (red) and Afp – GFP (green) in the mouse embryo. Endodermal precursors initially migrate from the streak in the mesenchymal layer but only begin to express Sox17 shortly before they egress into the endodermal epithelium. Below, a cartoon showing the acquisition of Sox17 expression by cells in the mesenchymal layer and their subsequent egression into the gut endoderm epithelium.

With the onset of gut tube formation, first a foregut pocket, constituting a local involution of the gut endoderm, and then a hindgut pocket emerge. Over time, these two pockets extend and finally meet, forming the gut tube. The gut tube exhibits extensive contribution of emVE-derived cells up until (at

approx. E8.75) the 15-somite stage [21] (figure 4).

8. A universal cell dispersal mechanism driving endoderm morphogenesis?

The core components of the gene-regulatory network involved in endoderm specification are largely conserved

across species [40]. The main transcription factors are ortholo-

gues of Foxa2, Sox17, T-box family members, Mix-like

proteins and Gata factors (figure 5). These factors are regu-

lated by Nodal, Wnt and FGF signalling inputs [75]. But

are the cellular dynamics of endoderm morphogenesis conserved, and to what extent might the dispersal model proposed in the mouse be applicable to other vertebrates?

The formulation of a model for gut endoderm morphogenesis in the chick has had a remarkably similar history to the mouse. During gastrulation, the chick embryo needs to reorganize its extraembryonic endodermal tissues (called hypoblast and endoblast) around newly generated DE. A series of fate-mapping experiments initially suggested an equivalent to the murine displacement model, namely that

DE precursors ingressed at the primitive streak and inserted into the extraembryonic endoderm tissues, gradually displacing them to the periphery of the embryo where they would

contribute primarily to extraembryonic tissues [76–80]. These

fate-mapping experiments were performed with techniques such as carbon particle and vital dye staining that proved sufficient to look at mass movements, but did not provide sufficient resolution to address the movements of all cells and their individual dynamics.

A lineage-tracing experiment using [H 3 ] thymidine revealed that the hypoblast does not move away from the

primitive streak as a uniform epithelium [81]. Instead,

during gastrulation, the gut endoderm is a mosaic layer

8

Downloaded from http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on March 6, 2016

Table 2.

Endoderm dynamics and fate across vertebrates.

extraembryonic and embryonic endoderm cells intermingle comigration of mesoderm and DE progenitors extraembryonic endoderm component to gut endoderm zebrafish

no

Xenopus

no

chick

yes [81] yes [82] yes/? [83,84]

rabbit

?

?

mouse

9 made of hypoblast and DE cells. After gastrulation, hypoblast cells had sorted to the germinal crescent (the extraembryonic region), but for a time, extraembryonic and embryonic endoderm lineages intermingled just as in the mouse. This was recently supported by a cell-labelling study which additionally showed that DE progenitors migrate in the mesoderm layer and then insert as single cells into different regions of the endoderm a few cell diameters away from the primitive

streak [82]. While the precise fate of the endoblast has not

yet been directly examined, chick –quail grafting experiments have suggested that the endoblast might not entirely sort to extraembryonic regions during DE formation, as is the case

for the hypoblast [83]. Further analysis using the endo-

blast-specific marker ApoA1 suggests that endoblast cells remain interspersed between primitive streak-derived DE cells to form the gut endoderm and eventually contribute

to the developing liver [84]. Together, these observations

beg the question of whether mixing of cells of two different origins may represent a general mode of endoderm formation across vertebrates.

In Xenopus , it is well established that three spatially and morphologically distinct populations of cells in the gastrula

stage embryo contribute cells to the gut [85,86]. In addition,

co-migration of mesoderm and DE progenitors was observed in a study in rabbit embryos in which the authors analysed the distribution of Sox17 expression during gastrulation

[87]. In zebrafish, on the other hand, it was shown that endo-

derm progenitors are restricted to the epiblast [37,88].

Together, these findings suggest that some elements of the dispersal model can be found in different vertebrates, arguing for conservation of the mechanism across species

(table 2). Further studies will be necessary to determine the

cell dynamics of the murine dispersal model across vertebrates and, notably, whether endoderm tissues in the adult human contain an extraembryonic component. In worms and flies, different germ layers contribute to the gut

tube [91], making a comparison difficult with vertebrates.

9. Concluding remarks

The advent of high-resolution live imaging techniques, which enable the visualization of entire populations of cells in realtime, is adding new insights to our understanding of the cellular dynamics that underlie critical morphogenetic events in vertebrate development. Nowhere is this more striking than the recent finding that so-called extraembryonic VE cells contribute to the gut endoderm. This finding opens up exciting possibilities with several important questions that remain to be answered. Do VE cells persist in the gut of the adult, or are they lost as embryonic development proceeds? If they do indeed persist, to which organs or tissues do VE descendants contribute? Do they behave any differently than their DE neighbours? What is their potential role in the adult? The next generation of live cell imaging tools that will allow for longer and more temporally regulated expression of lineage labels will allow us to investigate the fate of emVE-derived cells persisting within the gut endoderm.

Acknowledgements.

We thank Laina Freyer and Sonja Nowotschin for reading and commenting on this review.

References

1.

Bedzhov I, Graham SJL, Leung CY, Zernicka-Goetz M.

2014 Developmental plasticity, cell fate specification and morphogenesis in the early mouse embryo.

Phil.

Trans. R. Soc. B 369 , 20130538. (doi:10.1098/rstb.

2013.0538)

2.

Beddington RS, Robertson EJ. 1999 Axis development and early asymmetry in mammals.

Cell 96 , 195 – 209. (doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)

80560-7)

3.

Gardner RL. 1983 Origin and differentiation of extraembryonic tissues in the mouse.

Int. Rev. Exp.

Pathol.

24 , 63 – 133.

4.

Mesnard D, Guzman-Ayala M, Constam DB.

2006 Nodal specifies embryonic visceral endoderm and sustains pluripotent cells in the epiblast before overt axial patterning.

Development 133 , 2497 – 2505. (doi:10.1242/dev.

02413)

5.

Nowotschin S, Hadjantonakis AK. 2010 Cellular dynamics in the early mouse embryo: from axis formation to gastrulation.

Curr. Opin.

Genet. Dev.

20 , 420 – 427. (doi:10.1016/j.gde.

2010.05.008)

6.

Reinius S. 1965 Morphology of the mouse embryo, from the time of implantation to mesoderm formation.

Z. Zellforsch Mikrosk. Anat.

68 ,

711 – 723. (doi:10.1007/BF00340096)

7.

Solter D, Damjanov I, Skreb N. 1970 Ultrastructure of mouse egg-cylinder.

Z. Anat. Entwicklungsgesch.

132 , 291 – 298. (doi:10.1007/BF00569266)

8.

Rivera-Perez JA, Mager J, Magnuson T. 2003

Dynamic morphogenetic events characterize the mouse visceral endoderm.

Dev. Biol.

261 , 470 – 487.

(doi:10.1016/S0012-1606(03)00302-6)

9.

Srinivas S, Rodriguez T, Clements M, Smith JC,

Beddington RS. 2004 Active cell migration drives the unilateral movements of the anterior visceral endoderm.

Development 131 , 1157 – 1164. (doi:10.

1242/dev.01005)

10. Tam PP, Loebel DA. 2007 Gene function in mouse embryogenesis: get set for gastrulation.

Nat. Rev.

Genet.

8 , 368 – 381. (doi:10.1038/nrg2084)

11. Takaoka K, Yamamoto M, Hamada H. 2011 Origin and role of distal visceral endoderm, a group of cells that determines anterior – posterior polarity of the mouse embryo.

Nat. Cell Biol.

13 , 743 – 752.

(doi:10.1038/ncb2251)

12. Lu CC, Brennan J, Robertson EJ. 2001 From fertilization to gastrulation: axis formation in the mouse embryo.

Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev.

11 ,

384 – 392. (doi:10.1016/S0959-437X(00)00208-2)

13. Srinivas S. 2006 The anterior visceral endoderm— turning heads.

Genesis 44 , 565 – 572. (doi:10.1002/ dvg.20249)

Downloaded from http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on March 6, 2016

14. Tam PP, Khoo PL, Lewis SL, Bildsoe H, Wong N,

Tsang TE, Gad JM, Robb L. 2007 Sequential allocation and global pattern of movement of the definitive endoderm in the mouse embryo during gastrulation.

Development 134 , 251 – 260. (doi:10.

1242/dev.02724)

15. Trichas G, Joyce B, Crompton LA, Wilkins V,

Clements M, Tada M, Rodriguez TA, Srinivas S. 2011

Nodal dependent differential localisation of dishevelled-2 demarcates regions of differing cell behaviour in the visceral endoderm.

PLoS

Biol.

9 , e1001019. (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.

1001019)

16. Granier C et al . 2011 Nodal cis-regulatory elements reveal epiblast and primitive endoderm heterogeneity in the peri-implantation mouse embryo.

Dev. Biol.

349 , 350 – 362. (doi:10.1016/j.

ydbio.2010.10.036)

17. Lawson KA, Meneses JJ, Pedersen RA. 1986 Cell fate and cell lineage in the endoderm of the presomite mouse embryo, studied with an intracellular tracer.

Dev. Biol.

115 , 325 – 339. (doi:10.1016/0012-

1606(86)90253-8)

18. Lawson KA, Pedersen RA. 1987 Cell fate, morphogenetic movement and population kinetics of embryonic endoderm at the time of germ layer formation in the mouse.

Development 101 ,

627 – 652.

19. Tam PP, Beddington RS. 1987 The formation of mesodermal tissues in the mouse embryo during gastrulation and early organogenesis.

Development

99 , 109 – 126.

20. Thomas PQ, Brown A, Beddington RS. 1998 Hex: a homeobox gene revealing peri-implantation asymmetry in the mouse embryo and an early transient marker of endothelial cell precursors.

Development 125 , 85 – 94.

21. Kwon GS, Viotti M, Hadjantonakis AK. 2008 The endoderm of the mouse embryo arises by dynamic widespread intercalation of embryonic and extraembryonic lineages.

Dev. Cell 15 , 509 – 520.

(doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2008.07.017)

22. Morrisey EE, Tang Z, Sigrist K, Lu MM, Jiang F, Ip

HS, Parmacek MS. 1998 GATA6 regulates HNF4 and is required for differentiation of visceral endoderm in the mouse embryo.

Genes Dev.

12 , 3579 – 3590.

(doi:10.1101/gad.12.22.3579)

23. Kwon GS, Fraser ST, Eakin GS, Mangano M, Isern J,

Sahr KE, Hadjantonakis AK, Baron MH. 2006

Tg(Afp – GFP) expression marks primitive and definitive endoderm lineages during mouse development.

Dev. Dyn.

235 , 2549 – 2558. (doi:10.

1002/dvdy.20843)

24. Viotti M, Nowotschin S, Hadjantonakis AK. 2011

Afp::mCherry, a red fluorescent transgenic reporter of the mouse visceral endoderm.

Genesis 49 ,

124 – 133. (doi:10.1002/dvg.20695)

25. Tam PP, Loebel DA, Tanaka SS. 2006 Building the mouse gastrula: signals, asymmetry and lineages.

Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev.

16 , 419 – 425. (doi:10.1016/ j.gde.2006.06.008)

26. Arnold SJ, Robertson EJ. 2009 Making a commitment: cell lineage allocation and axis patterning in the early mouse embryo.

Nat. Rev.

Mol. Cell Biol.

10 , 91 – 103. (doi:10.1038/nrm2618)

27. Lewis SL, Tam PP. 2006 Definitive endoderm of the mouse embryo: formation, cell fates, and morphogenetic function.

Dev. Dyn.

235 ,

2315 – 2329. (doi:10.1002/dvdy.20846)

28. Yamaguchi TP, Harpal K, Henkemeyer M, Rossant J.

1994 fgfr-1 is required for embryonic growth and mesodermal patterning during mouse gastrulation.

Genes Dev.

8 , 3032 – 3044. (doi:10.1101/gad.8.

24.3032)

29. Ciruna B, Rossant J. 2001 FGF signaling regulates mesoderm cell fate specification and morphogenetic movement at the primitive streak.

Dev. Cell 1 ,

37 – 49. (doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(01)00017-X)

30. Sun X, Meyers EN, Lewandoski M, Martin GR. 1999

Targeted disruption of Fgf8 causes failure of cell migration in the gastrulating mouse embryo.

Genes

Dev.

13 , 1834 – 1846. (doi:10.1101/gad.13.14.1834)

31. Carver EA, Jiang R, Lan Y, Oram KF, Gridley T. 2001

The mouse snail gene encodes a key regulator of the epithelial – mesenchymal transition.

Mol. Cell.

Biol.

21 , 8184 – 8188. (doi:10.1128/MCB.21.23.

8184-8188.2001)

32. Arnold SJ, Hofmann UK, Bikoff EK, Robertson EJ.

2008 Pivotal roles for eomesodermin during axis formation, epithelium-to-mesenchyme transition and endoderm specification in the mouse.

Development 135 , 501 – 511. (doi:10.1242/ dev.014357)

33. Yanagisawa KO, Fujimoto H, Urushihara H. 1981

Effects of the Brachyury (T) mutation on morphogenetic movement in the mouse embryo.

Dev. Biol.

87 , 242 – 248. (doi:10.1016/0012-1606

(81)90147-0)

34. Hashimoto K, Fujimoto H, Nakatsuji N. 1987 An ECM substratum allows mouse mesodermal cells isolated from the primitive streak to exhibit motility similar to that inside the embryo and reveals a deficiency in the T / T mutant cells.

Development 100 ,

587 – 598.

35. McKnight KD, Hou J, Hoodless PA. 2010 Foxh1 and

Foxa2 are not required for formation of the midgut and hindgut definitive endoderm.

Dev. Biol.

337 ,

471 – 481. (doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.040)

36. Schock F, Perrimon N. 2002 Molecular mechanisms of epithelial morphogenesis.

Ann. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol.

18 , 463 – 493. (doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.18.

022602.131838)

37. Warga RM, Nusslein-Volhard C. 1999 Origin and development of the zebrafish endoderm.

Development 126 , 827 – 838.

38. Maduro MF, Meneghini MD, Bowerman B,

Broitman-Maduro G, Rothman JH. 2001 Restriction of mesendoderm to a single blastomere by the combined action of SKN-1 and a GSK-3 b homolog is mediated by MED-1 and -2 in C. elegans. Mol.

Cell 7 , 475 – 485. (doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(01)

00195-2)

39. Sulston JE, Schierenberg E, White JG, Thomson JN.

1983 The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode

Caenorhabditis elegans .

Dev. Biol.

100 , 64 – 119.

(doi:10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4)

40. Tremblay KD. 2010 Formation of the murine endoderm: lessons from the mouse, frog, fish, and chick.

Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci.

96 , 1 – 34. (doi:10.

1016/B978-0-12-381280-3.00001-4)

41. Robertson EJ. 2014 Dose-dependent Nodal/Smad signals pattern the early mouse embryo.

Semin. Cell

Dev. Biol.

32 , 73 – 79. (doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2014.

03.028)

42. Ding J, Yang L, Yan YT, Chen A, Desai N, Wynshaw-

Boris A, Shen MM. 1998 Dose-dependent Nodal/

Smad signals pattern the early mouse embryo.

Nature 395 , 702 – 707. (doi:10.1038/27215)

43. Weinstein DC, Marden J, Carnevali F, Hemmati-

Brivanlou A. 1998 Dose-dependent Nodal/Smad signals pattern the early mouse embryo.

Nature

394 , 904 – 908. (doi:10.1038/29808)

44. Zhou X, Sasaki H, Lowe L, Hogan BL, Kuehn MR.

1993 Nodal is a novel TGFb -like gene expressed in the mouse node during gastrulation.

Nature 361 ,

543 – 547. (doi:10.1038/361543a0)

45. Lowe LA, Yamada S, Kuehn MR. 2001 Genetic dissection of nodal function in patterning the mouse embryo.

Development 128 , 1831 – 1843.

46. Iratni R, Yan YT, Chen C, Ding J, Zhang Y,

Price SM, Reinberg D, Shen MM. 2002 Inhibition of excess nodal signaling during mouse gastrulation by the transcriptional corepressor DRAP1.

Science

298 , 1996 – 1999. (doi:10.1126/science.1073405)

47. Lickert H, Kutsch S, Kanzler B, Tamai Y, Taketo MM,

Kemler R. 2002 Formation of multiple hearts in mice following deletion of b -catenin in the embryonic endoderm.

Dev. Cell 3 , 171 – 181.

(doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00206-X)

48. Engert S, Burtscher I, Liao WP, Dulev S,

Schotta G, Lickert H. 2013 Wnt/-catenin signalling regulates Sox17 expression and is essential for organizer and endoderm formation in the mouse.

Development 140 , 3128 – 3138.

(doi:10.1242/dev.088765)

49. Burtscher I, Lickert H. 2009 Foxa2 regulates polarity and epithelialization in the endoderm germ layer of the mouse embryo.

Development 136 , 1029 – 1038.

(doi:10.1242/dev.028415)

50. Viotti M, Niu L, Shi SH, Hadjantonakis AK. 2012

Role of the gut endoderm in relaying left – right patterning in mice.

PLoS Biol.

10 , e1001276.

(doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001276)

51. Spiegelman M, Bennett D. 1974 Fine structural study of cell migration in the early mesoderm of normal and mutant mouse embryos (T-locus: t-9/t-

9).

J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol.

32 , 723 – 728.

52. Tam PP, Meier S. 1982 The establishment of a somitomeric pattern in the mesoderm of the gastrulating mouse embryo.

Am. J. Anat.

164 ,

209 – 225. (doi:10.1002/aja.1001640303)

53. Yang D, Lutter D, Burtscher I, Uetzmann L, Theis FJ,

Lickert H. 2014 miR-335 promotes mesendodermal lineage segregation and shapes a transcription factor gradient in the endoderm.

Development 141 ,

514 – 525. (doi:10.1242/dev.104232)

54. Lolas M, Valenzuela PD, Tjian R, Liu Z. 2014

Charting Brachyury-mediated developmental pathways during early mouse embryogenesis.

Proc.

10

Downloaded from http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/ on March 6, 2016

Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111 , 4478 – 4483. (doi:10.1073/ pnas.1402612111)

55. Leroy P, Mostov KE. 2007 Slug is required for cell survival during partial epithelial – mesenchymal transition of HGF-induced tubulogenesis.

Mol.

Biol. Cell 18 , 1943 – 1952. (doi:10.1091/mbc.E06-

09-0823)

56. Huber MA, Kraut N, Beug H. 2005 Molecular requirements for epithelial – mesenchymal transition during tumor progression.

Curr. Opin. Cell Biol.

17 ,

548 – 558. (doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2005.08.001)

57. Hart AH, Hartley L, Sourris K, Stadler ES, Li R,

Stanley EG, Tam PP, Elefanty AG, Robb L. 2002

Mixl1 is required for axial mesendoderm morphogenesis and patterning in the murine embryo.

Development 129 , 3597 – 3608.

58. Kanai-Azuma M et al . 2002 Depletion of definitive gut endoderm in Sox17-null mutant mice.

Development 129 , 2367 – 2379.

59. Ang SL, Rossant J. 1994 HNF-3 b is essential for node and notochord formation in mouse development.

Cell 78 , 561 – 574. (doi:10.1016/

0092-8674(94)90522-3)

60. Tamplin OJ, Kinzel D, Cox BJ, Bell CE, Rossant J, Lickert

H. 2008 Microarray analysis of Foxa2 mutant mouse embryos reveals novel gene expression and inductive roles for the gastrula organizer and its derivatives.

BMC

Genomics 9 , 511. (doi:10.1186/1471-2164-9-511)

61. Niakan KK et al . 2010 Sox17 promotes differentiation in mouse embryonic stem cells by directly regulating extraembryonic gene expression and indirectly antagonizing self-renewal.

Genes Dev.

24 , 312 – 326. (doi:10.1101/gad.1833510)

62. Niimi T, Hayashi Y, Futaki S, Sekiguchi K. 2004 SOX7 and SOX17 regulate the parietal endoderm-specific enhancer activity of mouse laminin 1 gene.

J. Biol.

Chem.

279 , 38 055 – 38 061. (doi:10.1074/jbc.

M403724200)

63. Shirai T et al . 2005 Identification of an enhancer that controls up-regulation of fibronectin during differentiation of embryonic stem cells into extraembryonic endoderm.

J. Biol. Chem.

280 ,

7244 – 7252. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M410731200)

64. Artus J, Piliszek A, Hadjantonakis AK. 2011 The primitive endoderm lineage of the mouse blastocyst: sequential transcription factor activation and regulation of differentiation by Sox17.

Dev. Biol.

350 , 393 – 404. (doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.12.007)

65. Loebel DA et al . 2011 Rhou maintains the epithelial architecture and facilitates differentiation of the foregut endoderm.

Development 138 , 4511 – 4522.

(doi:10.1242/dev.063867)

66. Weinstein DC, Ruiz i Altaba A, Chen WS, Hoodless P,

Prezioso VR, Jessell TM, Darnell Jr JE. 1994 The winged-helix transcription factor HNF-3 b is required for notochord development in the mouse embryo.

Cell 78 , 575 – 588. (doi:10.1016/0092-

8674(94)90523-1)

67. Dufort D, Schwartz L, Harpal K, Rossant J. 1998 The transcription factor HNF3 b is required in the visceral endoderm for normal primitive streak morphogenesis.

Development 125 , 3015 – 3025.

68. Trichas G et al . 2012 Multi-cellular rosettes in the mouse visceral endoderm facilitate the ordered migration of anterior visceral endoderm cells.

PLoS

Biol.

10 , e1001256. (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.

1001256)

69. Bort R, Martinez-Barbera JP, Beddington RS, Zaret

KS. 2004 Hex homeobox gene-dependent tissue positioning is required for organogenesis of the ventral pancreas.

Development 131 , 797 – 806.

(doi:10.1242/dev.00965)

70. Molotkov A, Molotkova N, Duester G. 2005 Retinoic acid generated by Raldh2 in mesoderm is required for mouse dorsal endodermal pancreas development.

Dev. Dyn.

232 , 950 – 957. (doi:10.

1002/dvdy.20256)

71. Serls AE, Doherty S, Parvatiyar P, Wells JM, Deutsch

GH. 2005 Different thresholds of fibroblast growth factors pattern the ventral foregut into liver and lung.

Development 132 , 35 – 47. (doi:10.1242/ dev.01570)

72. Tremblay KD, Zaret KS. 2005 Distinct populations of endoderm cells converge to generate the embryonic liver bud and ventral foregut tissues.

Dev. Biol.

280 , 87 – 99. (doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.

01.003)

73. Villegas SN, Rothova M, Barrios-Llerena ME, Pulina

M, Hadjantonakis AK, Le Bihan T, Astrof S, Brickman

JM. 2013 PI3K/Akt1 signalling specifies foregut precursors by generating regionalized extra-cellular matrix.

eLife 2 , e00806. (doi:10.7554/eLife.00806)

74. Cheng P, Andersen P, Hassel D, Kaynak BL,

Limphong P, Juergensen L, Kwon C, Srivastava D.

2013 Fibronectin mediates mesendodermal cell fate decisions.

Development 140 , 2587 – 2596. (doi:10.

1242/dev.089052)

75. Zorn AM, Wells JM. 2007 Molecular basis of vertebrate endoderm development.

Int. Rev.

Cytol.

259 , 49 – 111. (doi:10.1016/S0074-

7696(06)59002-3)

76. Vakaet L. 1962 Some new data concerning the formation of the definitive endoblast in the chick embryo.

J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol.

10 , 38 – 57.

77. Vakaet L. 1970 Cinephotomicrographic investigations of gastrulation in the chick blastroderm.

Arch. Biol.

( Liege ) 81 , 387 – 426.

78. Rosenquist GC. 1971 The location of the pregut endoderm in the chick embryo at the primitive streak stage as determined by radioautographic mapping.

Dev. Biol.

26 , 323 – 335. (doi:10.1016/

0012-1606(71)90131-X)

79. Solursh M, Revel JP. 1978 A scanning electron microscope study of cell shape and cell appendages in the primitive streak region of the rat and chick embryo.

Differentiation 11 , 185 – 190. (doi:10.1111/ j.1432-0436.1978.tb00983.x)

80. Spratt Jr NT, Haas H. 1960 Integrative mechanisms in development of the early chick blastoderm. I.

Regulative potentiality of separated parts.

J. Exp. Zool.

145 , 97 – 138. (doi:10.1002/jez.

1401450202)

81. Azar Y, Eyal-Giladi H. 1983 The retention of primary hypoblastic cells underneath the developing primitive streak allows for their prolonged inductive influence.

J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol.

77 , 143 – 151.

82. Kimura W, Yasugi S, Stern CD, Fukuda K. 2006 Fate and plasticity of the endoderm in the early chick embryo.

Dev. Biol.

289 , 283 – 295. (doi:10.1016/j.

ydbio.2005.09.009)

83. Bachvarova RF, Skromne I, Stern CD. 1998 Induction of primitive streak and Hensen’s node by the posterior marginal zone in the early chick embryo.

Development 125 , 3521 – 3534.

84. Bertocchini F, Stern CD. 2008 A differential screen for genes expressed in the extraembryonic endodermal layer of pre-primitive streak stage chick embryos reveals expression of Apolipoprotein A1 in hypoblast, endoblast and endoderm.

Gene Expr.

Patterns 8 , 477 – 480. (doi:10.1016/j.gep.2008.

07.001)

85. Keller RE. 1975 Vital dye mapping of the gastrula and neurula of Xenopus laevis .

Dev. Biol.

42 ,

222 – 241. (doi:10.1016/0012-1606(75)90331-0)

86. Keller RE. 1976 Vital dye mapping of the gastrula and neurula of Xenopus laevis .

Dev Biol 51 ,

118 – 137. (doi:10.1016/0012-1606(76)90127-5)

87. Hassoun R, Puschel B, Viebahn C. 2010 Sox17 expression patterns during gastrulation and early neurulation in the rabbit suggest two sources of endoderm formation.

Cells Tissues Organs 191 ,

68 – 83. (doi:10.1159/000236044)

88. Kimmel CB, Warga RM, Schilling TF. 1990 Origin and organization of the zebrafish fate map.

Development 108 , 581 – 594.

89. Pezeron G, Mourrain P, Courty S, Ghislain J, Becker

TS, Rosa FM, David NB. 2008 Live analysis of endodermal layer formation identifies random walk as a novel gastrulation movement.

Curr. Biol.

18 ,

276 – 281. (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.01.028)

90. Hadjantonakis AK, Macmaster S, Nagy A. 2002 Live analysis of endodermal layer formation identifies random walk as a novel gastrulation movement.

BMC

Biotechnol.

2 , 11. (doi:10.1186/1472-6750-2-11)

91. Zaret K. 1999 Developmental competence of the gut endoderm: genetic potentiation by GATA and

HNF3/fork head proteins.

Dev. Biol.

209 , 1 – 10.

(doi:10.1006/dbio.1999.9228)

11