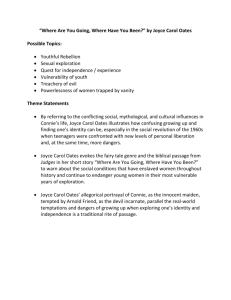

Joyce Carol Oates's Early Short Stories

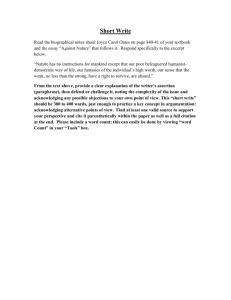

advertisement