BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

by

Kevin T. Martin

BVE, RRT, RCP

RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc.

16781 Van Buren Blvd, Suite B, Riverside, CA 92504-5798

(800) 441-LUNG / (877) 367-NURS

www.RCECS.com

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

BEHAVIORAL OBJECTIVES

UPON COMPLETION OF THE READING MATERIAL, THE PRACTITIONER WILL BE

ABLE TO:

1. Define bacterial pneumonia.

2. List three predisposing factors to bacterial pneumonia.

3. Define nosocomial pneumonia.

4. List three types of patients who are at especially high risk for contracting bacterial

pneumonia.

5. List and define the four types of bacterial pneumonia.

6. Describe the most common physical presentations of the patient with bacterial pneumonia.

7. Summarize the laboratory findings which would indicate a bacterial infection.

8. Describe the radiologic findings of bacterial pneumonia.

9. List the three major foci in the treatment of pneumonia.

10. Briefly summarize the findings in atypical pneumonia syndrome.

11. Explain the pathology of ventilator-associated pneumonia.

COPYRIGHT © 1991 By RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc.

COPYRIGHT © April, 2000 By RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc.

(# TX 0-480-589)

Authored by: Kevin T. Martin, BVE, RRT, RCP

Revised 1994, 1997 by Kevin T. Martin, BVE, RRT, RCP

Revised 2001 by Susan Jett Lawson, RCP, RRT-NPS

Revised 2004 by Helen Schaar Corning, RRT, RCP

Revised 2007 by Michael R. Carr, BA, RRT, RCP

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

This course is for reference and education only. Every effort is made to ensure that the clinical

principles, procedures and practices are based on current knowledge and state of the art

information from acknowledged authorities, texts and journals. This information is not intended

as a substitution for a diagnosis or treatment given in consultation with a qualified health care

professional.

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

2

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DEFINITION AND INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................ 6

TYPES OF BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA ..................................................................................... 6

Community Acquired................................................................................................................ 6

Hospital Acquired ..................................................................................................................... 7

Typical ...................................................................................................................................... 7

Atypical..................................................................................................................................... 8

PATHOLOGY ............................................................................................................................... 8

Pathogenic Mechanisms Responsible For Pneumonia ............................................................. 9

PREDISPOSING FACTORS ..................................................................................................... 10

Nosocomial Pneumonia .......................................................................................................... 11

Neisseria Meningitidis ............................................................................................................ 11

High Risk Situations In The Hospital ..................................................................................... 12

Predisposing And High Risk Factors Of Nosocomial Pneumonia ......................................... 13

DIAGNOSIS ................................................................................................................................ 14

HISTORY AND CLINICAL PRESENTATION ........................................................................ 14

History..................................................................................................................................... 16

Physical................................................................................................................................... 16

LABORATORY EVALUATION ............................................................................................... 17

Laboratory Studies .................................................................................................................. 18

INVASIVE DIAGNOSTIC TECHNIQUES ............................................................................... 18

Invasive Diagnostic Procedures.............................................................................................. 19

RADIOLOGIC EVALUATION.................................................................................................. 19

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

3

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

Imaging Studies....................................................................................................................... 20

Chest X-Ray............................................................................................................................ 20

CT Scan................................................................................................................................... 20

Diagnosis Of Pneumonia ........................................................................................................ 20

TREATMENT ............................................................................................................................. 21

Antibiotics ............................................................................................................................... 21

Summary Of Antibiotic Therapy For Bacterial Pneumonia ................................................... 22

Correction Of Reversible Patient Abnormalities .................................................................... 23

Supportive Care....................................................................................................................... 23

Treatment Of Pneumonia ........................................................................................................ 24

COMPLICATIONS ..................................................................................................................... 24

Additional Complications Of Bacterial Pneumonia ............................................................... 25

TREATMENT AND CLINICAL MANISFESTATION OF STREPTOCOCCUS

AND STAPHLOCOCCUS PNEUMONIA ................................................................................. 25

STREPTOCOCCUS PNEUMONIA (PNEUMOCOCCUS) - (TYPICAL PNEUMONIA) ....... 25

Clinical Manifestation............................................................................................................. 26

Treatment ................................................................................................................................ 27

STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS - (TYPICAL PNEUMONIA) ................................................ 27

Clinical Manifestation............................................................................................................. 29

Treatment ................................................................................................................................ 29

HEMOPHILUS INFLUENZA - (ATYPICAL PNEUMONIA).................................................. 30

Clinical Manifestation............................................................................................................. 30

Treatment ................................................................................................................................ 31

KLEBSIELLA PNEUMONIA - (HOSPITAL ACQUIRED) ..................................................... 31

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

4

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

Clinical Manifestation............................................................................................................. 31

Treatment ................................................................................................................................ 32

PSEUDOMONAS AERUGINOSA - (HOSPITAL ACQUIRED).............................................. 32

Clinical Manifestation (Nonbacterial vs bacterial) ................................................................. 33

Treatment ................................................................................................................................ 34

Anaerobic Bacteria.................................................................................................................. 34

Clinical Manifestations ........................................................................................................... 34

Microbiological Diagnosis ...................................................................................................... 35

Treatment ................................................................................................................................ 35

Prevention ............................................................................................................................... 36

ATYPICAL PNEUMONIA SYNDROME ................................................................................. 36

Epidemiology.......................................................................................................................... 36

Clinical Manifestations .......................................................................................................... 36

Treatment And Prevention...................................................................................................... 37

VENTILATOR-ASSOCIATED PNEUMONIA ......................................................................... 37

Diagnosis In The Mechanically Ventilated Patient ................................................................ 38

CLINICAL PRACTICE EXERCISE .......................................................................................... 39

SUMMARY................................................................................................................................. 39

PRACTICE EXERCISE DISCUSSION...................................................................................... 40

SUGGESTED READING AND REFERENCES ....................................................................... 42

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

5

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

DEFINITION AND INTRODUCTION

P

neumonia is an acute inflammation of the pulmonary parenchyma caused by bacteria,

viruses, mycoplasma and other agents. According to recent Center for Disease Control

(CDC) reports, pneumonia is the fourth leading cause of death in geriatric patients in the

United States. There are over three million cases of pneumonia per year in the U.S.

Pneumonia (nosocomial) is responsible for the greatest mortality of patients in hospitals, at a rate

ranging from 30% to 60%. This pulmonary infection accounts for approximately 50,000 deaths

per year. Nosocomial pneumonia occurs in approximately 27% of patients on mechanical

ventilation.1 Approximately 12-29% of critically ill, hospitalized patients develop pneumonia.

Around 50-60% of ARDS patients develop some form of pneumonia. This course is primarily,

but not limited to discussing bacterial pneumonia, since it is the one most often encountered in

the acute care setting.

Bacterial pneumonia is caused by a pathogenic infection of the lungs from bacteria.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common source of bacterial pneumonia.2 Bacterial

pneumonia is also the most common fatal nosocomial (iatrogenic) infection. Most fatalities of

bacteremic pneumonia occur in less than 7 days. Survivors are hospitalized 3 weeks or more.

Pneumonia is more likely to occur in the winter months, when upper and lower track respiratory

infections caused by viruses precipitate a bacterial superinfection. There is a higher incidence in

males than in females. The elderly are at a higher risk due to fewer defenses against aspiration

and less receptive immune responses.

TYPES OF BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

T

here are four types of bacterial pneumonia based upon how it is acquired and its clinical

course. Bacterial pneumonia may be community or hospital-acquired. The clinical

course can take a typical or atypical path. I use this classification system for the following

discussion. Others choose to use a classification system based upon the type of host and nature

of the organism. This system also delineates four types of pneumonia: normal/abnormal host

and usual/unusual organisms. The former refers to whether the host (patient) has normal, or

abnormal defense mechanisms against infection, the latter is self-explanatory. “Usual”

organisms consist of Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), Hemophilus influenzae,

Chlamydia species, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, or common viruses. “Unusual” organisms consist

of Legionella pneumophila, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Bacillus anthracis, group A betahemolytic streptococcus, Meningococcus, and endemic fungi.

Another classification system in the causes for development of pneumonia is extrinsic and

intrinsic differentiation. Extrinsic includes exposure to the causative agent, exposure to

pulmonary irritants or direct pulmonary injury. Intrinsic factors are related to the host only.

(1) Community Acquired - The patient usually presents with a cough, fever and consolidation

on the chest x-ray (CXR) with community-acquired pneumonia. Pneumococcus is probably the

most common causative agent. This type of pneumonia generally responds readily to treatment

and causes few serious problems. Approximately 95% of normal adults with community

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

6

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

acquired pneumonia have “usual” organisms.

(2) Hospital Acquired - Nosocomial or iatrogenic pneumonia accounts for about 15% of all

hospital-acquired infections, and 31% of those in ICU. An average 27% of mechanically

ventilated patients and 12-29% of ICU patients acquire nosocomial pneumonia. Nosocomial

pneumonia is responsible for up to 33% of all nosocomial deaths.1 It increases hospital length of

stay from 4-13 days and is the most expensive infection by site. About 60% of nosocomial

pneumonias are gram-negative organisms. The most common organisms, which comprise 50%

of isolates from cultures of respiratory tract specimens, include: Pseudomonas aeruginosa,

Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter species, Escherichia coli, Serratia marcescens, and Proteus

species. However, gram-positive cocci have emerged recently as isolates, with increasing

frequency. Gram-positive cocci causing concern include Staphylococcus aureus, and

Streptococcus pneumoniae.

The integrity of the pulmonary defenses is a critical factor in assessing the risk for nosocomial

pneumonia. Severe underlying disease makes a patient very high-risk for nosocomial

pneumonia. Those in ICU, intubated, and mechanical ventilated are an even higher risk.

Immunodeficiency states (neutropenia, hematologic malignancy, immunosuppression therapy,

AIDS) are susceptible to a wide variety of pathogens thereby increasing the risk of nosocomial

pneumonia.

Once the diagnosis of pneumonia is suspected on a patient, a sputum and blood culture should be

obtained. Empirical therapy can be instituted based upon gram stain results and the

susceptibility patterns for organisms in the particular institution. A note of caution is warranted

with decisions based on sputum cultures. Sputum cultures reveal the causative agent of

pneumonia only around 50% of the time.

(3) Typical - Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common typical pneumonia. Hemophilus

influenzae and Klebsiella pneumoniae have an identical clinical picture to streptococcus. All

begin with an abrupt onset of fever and shaking chills. A productive cough of purulent sputum is

also common and, patients complain of pleuritic chest pain. Patients may have had symptoms of

an upper respiratory infection prior to the pneumonia. Elderly and debilitated patients may also

be hypothermic.

Physical examination of a typical pneumonia patient reveals consolidation with dullness to

percussion. The patients’ white blood count (WBC) is usually increased, but can be normal or

low, particularly in the COPD or immunodeficient patient. An increase in immature white blood

cells and toxic granulations are usually found. Sputum gram stains show many white blood cells

and predominant bacteria, indicative of the causative organism. A predominant and/or causative

organism may not be present if the patient has taken antibiotics before the test.

The CXR confirms consolidation and may show a variety of findings that include

bronchopneumonic infiltrates and/or interstitial infiltrates. Pleural effusions are common on

CXR but usually small in volume. Cavitation of the lung is unusual but suggests staphylococcus

aureus or endocarditis (particularly in IV drug users), gram-negative bacilli, or a mixed

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

7

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

anaerobic infection. Other causes of cavitation include mycobacterium tuberculosis,

malignancies, and aocardiosis. Hemophilus influenzae produces a multilobar or segmental

consolidation and a large pleural effusion may rapidly accumulate. Klebsiella pneumoniae is

characterized by accumulation of large amounts of inflammatory exudate. The CXR often

reveals upper lobe consolidation, abscess formation, and bulging interlobular fissures.

Aspiration pneumonia develops in the pulmonary segments that were dependent when the

aspiration occurred. Pleural effusion and eventual cavitation are common in these patients.

Patients presenting with symptoms indicating a typical bacterial pneumonia should be assumed

to have pneumococcal disease until proven otherwise. This organism accounts for the majority

of pneumonias in this category. Penicillin is recommended for treatment but erythromycin may

be substituted. Many strains have become resistant to traditional antibiotics. (Individual

organisms and medications are discussed in detail later).

(4) Atypical - This differs from typical pneumonia in several respects. The onset is insidious

and headache, sore throat, muscle pain, and fatigue are common. Fever is present, but chills are

uncommon. Physical examination reveals scattered rhonchi or crackles. Evidence of

consolidation is minimal or absent. Sputum examination shows neutrophils but few organisms.

The WBC may be slightly elevated and the blood culture negative.

Mycoplasma pneumoniae accounts for the majority of atypical cases in the United States.

Respiratory viruses, legionella species and other unusual organisms account for the remainder.

The CXR in mycoplasma pneumonia may show a subsequent infiltrate in the lower lobes or a

diffuse reticulonodular interstitial infiltrate. The CXR in legionella infections is more variable

and may progress dramatically.

PATHOLOGY

he first phase of pneumonia is the invasion of body tissues. It is important to note that

invasion, not simply contamination or colonization, is the key word. Many patients are

contaminated, but invasion does not take place. These cases do not progress to pneumonia

because invasion of body tissues requires bacterial adherence to host cells. Severe illness,

malnutrition, surgery, and intubation enhance adherence and aid invasion. Some invading

organisms have an increased affinity for particular types of host cells. For example,

Pseudomonas, has a higher affinity for tracheal and lower respiratory tract cells than cells of the

upper respiratory tract. Therefore, it is more likely to cause pneumonia than an upper respiratory

infection. The initial invasion of tissue is usually from a few bacteria that multiply rapidly. This

results in numerous body responses.

T

Lymph cells within the tracheobronchial (TB) tree begin producing and secreting

immunoglobulins (antibodies) into respiratory tract secretions. Additional immunoglobulin is

transferred from the bloodstream to the respiratory tract. Immunoglobulin G (IgG) and

immunoglobulin A (IgA) coat the invading organism. The process of coating this organism with

immunoglobulin aids in its attachment to the surface of a macrophage. This procedure is known

as Opsonization. Opsonization enhances phagocytosis by alveolar macrophages.

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

8

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

Alveolar macrophages begin releasing chemotactic materials to cause an influx of edema fluid in

the area. This is followed by migration of leukocytes (WBC’s) and erythrocytes (RBC’s) into

the lung. A leukocyte-rich exudate therefore forms in the alveolus.

The leukocytes begin phagocytosis by compressing invading bacteria against the alveolar wall or

other leukocytes. Cytoplasmic pseudopods are then extended to surround and ingest the foreign

organism.

Several distinct zones gradually develop within the alveolus during this process. The lowermost

zone is filled with dead bacteria, leukocytes, and fibrin. The middle zone contains active

bacteria and leukocytes conducting phagocytosis. The upper zone is primarily edema fluid. This

upper zone supports further bacterial multiplication. These zones are similar to battlefields. The

middle zone is where the battle is currently raging. The upper zone is where the bacteria have

control and the lower zone is where the leukocytes have control. The entire process is enhanced

by the appearance of a specific antibody (such as IgG or IgA) to the invading organism. This

intensifies the body’s response. When the invasion is stopped, resolution begins in the lower

zone with absorption of fluid.

During the acute phase the affected area remains perfused but there is no gas exchange. A rightto-left shunt exists, resulting in a decrease in PaO2 . If the ventilatory reserve is normal,

remaining areas are hyperventilated. This results in a decrease in PaCO2 . However, if the

patient is unable to compensate for the loss of consolidated alveoli, the PaCO2 increases, and can

result in respiratory failure. On any given patient, the effect on arterial blood gases is related to

the extent of consolidation and ventilation of the remaining lung area.

Initially, the consolidated area is firm, airless, and reddish in color. This is commonly referred to

as the “red hepatization” stage. These alveoli are filled with RBC’s, fibrin, and contain relatively

few leukocytes (primarily neutrophils). Alveolar capillaries are congested around consolidated

areas in the red hepatization phase.

In the “grey hepatization” stage, consolidation composition changes to many neutrophils and

relatively few RBC’s in the alveoli. The capillaries are less congested and phagocytosis

continues. The alveolar exudate begins to loosen and be disposed of via coughing. Fluid is

readily reabsorbed through the alveolar wall. However, larger exudative particles and molecules

cannot be absorbed back through the alveolar wall. These larger particles/molecules often

become scar tissue. Therefore, fibrosis, hyaline membranes, abscess, and loss of lung

parenchyma may remain following resolution of pneumonia.

Pathogenic Mechanisms Responsible for Pneumonia:

•

Aspiration of colonizing organisms in the oropharynx can result in aspiration

pneumonia, Nosocomial pneumonia, and community-acquired bacterial pneumonia.

•

Inhalation of aerosolized infectious particles can result in Tuberculosis,

Legionellosis, Histoplasmosis, Cryptococcosis, Blastomycosis, Coccidiodomycosis,

Aspergillosis, or Q fever.

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

9

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

•

Direct inoculation of infectious organisms into the lower airway can result in

nosocomial pneumonia.

•

Spread of infection from the blood to the lungs can result in S. aureus pneumonia, or

parasitic pneumonia.

•

Spread of infection from adjacent structures to the lungs can result in mixed

anaerobic and aerobic pneumonia, or amebic pneumonia.

•

Reactivation of a latent infection (usually occurs in immunocompromised patients)

can result in Reactivation tuberculosis, P. carinii pneumonia, or cytomegalovirus.4

PREDISPOSING FACTORS

P

redisposing factors to pneumonia are related to virulence of the organism and deficiencies

in the patient’s immunity, particularly lung immunity.

The presence of a protective polysaccharide capsule surrounding the organism increases its

virulence. Organisms with such a capsule require a specific immunoglobulin for phagocytosis to

occur readily. Without such a specific immunoglobulin, phagocytosis is impaired and bacterial

multiplication proceeds rapidly. Streptococcus pneumoniae is an example of an organism with a

polysaccharide capsule. Other organisms produce toxins, such as, coagulase and leukocidin,

making them more virulent. These toxins delay phagocytosis and may be toxic to leukocytes.

Staphylococcus is an example of such an organism. It produces both coagulase and leukocidin

along with other toxins.

Many deficiencies of patient immunity are possible. There can be an overall deficiency or a

specific lung deficiency. General deficiencies include: debilitation, malnutrition, chronic

diseases, alcoholism, smoking, immunosuppressive therapy and hypogammaglobinemia or

disgammaglobinemia. These general deficiencies make a patient more susceptible to any

infection. Specific lung deficiencies make the lung more susceptible to infection. For example,

a deficiency in lung IgG means no opsonization of invading bacteria. Therefore, there is little

phagocytosis and bacterial multiplication is unhindered.

Infection is also more likely if the respiratory epithelium is damaged from acute or chronic

pulmonary disease. An upper respiratory tract infection (URI) or previous pulmonary disease

therefore make invasion more likely. Intubation renders all the upper airway defenses useless so

it obviously predisposes to pneumonia.

There are numerous other predisposing factors to pneumonia. Diabetes and chronic renal disease

also lower one’s defenses. Travel and/or exposure to wild animals can predispose to tularemia,

plague, or psittacosis. Alcoholic intoxication, stroke and other conditions that disrupt the normal

glottic reflexes increase the amount of aspirated material during sleep. Even small amounts of

aspirated material can produce a chemical or bacterial pneumonia. Most people aspirate minute

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

10

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

amounts of oral secretions during sleep that causes no problems. Neurological impairment

increases the amount and can result in pneumonia.

Nosocomial Pneumonia - Nosocomial pneumonia has additional predisposing factors to those

listed above. Intubation and mechanical ventilation increase the risk of a hospital-acquired

pneumonia considerably. The risk increases significantly after three days of intubation.

Thereafter, the rate of infection increases approximately 1% per day for each day of intubation.

Frequent changes of tubing attached to the airway are associated with an increased incidence of

infection. In the past it was believed that frequent changes of contaminated tubing prevented

infection. This has been proven false. The more frequently the circuit is “opened” from circuit

changes, suctioning, or other procedures, the greater the risk of infection.

Critical Care Unit patients have a higher incidence of nosocomial pneumonia, particularly those

in surgical intensive care. These patients are more likely than the general hospital population to

develop pneumonia. Additional factors are advanced age (more than 65 years old),

inappropriate antibiotic or antacid therapy. The latter increases gastric pH allowing an increase

in gastric colonization. If aspiration occurs, there is a significant increase in the number of

organisms present. Nasogastric feeding and continuous enteral feeding are additional risk factors

for nosocomial pneumonia. Patients often aspirate subclinical amounts of tube feedings over

extended periods. This leads to pneumonia.

Neisseria Meningitidis - This is an unusual and sporadic cause of pneumonia, but is welldocumented as a cause of epidemic pneumonias, particularly among military recruits. Five to ten

per cent of asymptomatic individuals transiently carry neisseria in the nose. Transmission is

mainly through aerosol droplets, but direct hand contact also may be a means of transmission.

Neisseria is an aerobic, oxidase-positive, gram-negative, diplococcus. It will not survive drying

or exposure to cold, so rapid processing of specimens is essential. Blood, cerebrospinal fluid,

and pleural fluid rarely yield the organism. Diagnosis depends upon a sputum or TTA specimen.

TTA is the most appropriate way to document invasive infection. If an epidemic is present,

recovery from expectorated sputum is sufficient for diagnosis. Clinical course and prognosis for

neisseria pneumonia are excellent. There are few deaths and the incidence of empyema or

septicemia is low.

Clinical manifestation is of URI, fever, chills, productive cough, and chest pain at the onset.

Pharyngitis and scattered crackles are typical. Frank consolidation occurs, particularly in the

right lower and middle lobes. Neisseria infection is usually confined to the lungs. The CXR

shows a lower lobe bronchopneumonia, or in some cases, multilobar involvement. Pleural

effusion occurs in about 20% of patients.

Aqueous penicillin G is again the therapeutic choice. In adults, 4-6 million units given IV for 10

days is recommended. The dose should be increased to 20 million units per day for septicemia

or meningitis. Chloramphenicol is used for those allergic to penicillin. Some types of neisseria

are resistant to sulfonamide antibiotics. Patients should be placed in respiratory isolation for the

initial days of treatment. Chemoprophylaxis with rifampin, 600 mg twice daily for 2 days, is

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

11

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

advisable for those with close contact with the patient.

High-Risk Situations In The Hospital - There are several high-risk situations for bacterial

pneumonia that are worth mentioning. Granulocytopenia, corticosteroid therapy, bone marrow,

heart or renal transplantation, dental procedures, antibiotics, and autoimmune deficiency

syndrome (AIDS) put a patient in a high-risk category for pneumonia. Lower respiratory tract

infections in these patients are a common cause of morbidity and mortality.

Granulocytopenia is a frequent complication of treatment for malignancies. A low granulocyte

count also can be the result of primary disease. Patients may be selectively or completely

immunodeficient. Since there is a decrease in the systemic supply of phagocytic cells, the lungs

lack these cells when pneumonia develops. Therefore, there are no granulocytes to attract into

the site of infection. The lung must rely solely on the alveolar macrophages for phagocytosis.

This gives the infection more time to become established, since there are fewer cells fighting it.

A granulocyte (neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils) count less than 1000 cells/cu mm is a highrisk situation. The incidence of infection and mortality is directly related to the decrease in the

number of granulocytes. Empirical therapy with antipseudomonal penicillin or cephalosporin

and an aminoglycoside should be instituted for pneumonia after appropriate cultures have been

obtained in these patients. Antibiotics with bactericidal activity should be used and an

antistaphylococcal agent is recommended. Relapses occur if the antibiotic is discontinued before

the granulocytes have recovered. A relapse can occur even if the patient has clinically improved.

One must note the chest X-ray may underestimate the severity of the infection because the

inflammatory response is decreased in these patients. Vascular congestion, fluid migration, and

consolidation do not show up on the CXR as readily as with other patients since they have a

minimal inflammatory response.

Corticosteroid therapy increases the risk of all infections. Corticosteroids impede the migration

of white blood cells into the infection site, decrease phagocytosis by macrophages, and interfere

with white blood cell chemotaxis. Obviously, this increases the possibility of pneumonia.

Steroids also interfere with lysosomal enzymes released from white blood cells and

macrophages. This decreases their ability to kill the invading organism. Cytotoxic drugs used

for malignancies also decrease the inflammatory response. They impede development of

immunoglobulin-producing cells that manufacture antibodies. Radiation therapy can have the

same effect.

Pulmonary complications are a frequent complication in bone marrow transplantation. If

interstitial infiltrates develop within two weeks of the transplant, it may be a toxic reaction to

radiation or chemotherapy. Some patients develop a fatal, progressive interstitial infiltrate from

two weeks to several months after the transplant. These are usually due to cytomegalovirus

(CMV). Cytomegalovirus is often the cause of progressive interstitial pneumonia in heart and

renal transplants. There is also a high mortality in these patients.

Recent dental procedures and/or antibiotic use predispose to pneumonia. Dental procedures

introduce many organisms into the lower respiratory tract. Antibiotics give opportunistic

pathogens a chance to cause infection by reducing competing pathogens. Malignancy,

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

12

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

particularly with poor nutrition, is associated with decreased cell-mediated immunity and an

increase in infection that may result in pneumonia. Lymphoproliferative disorders and other

immune deficiency states are also predispose to pneumonia from opportunistic pathogens.

The incidence of pulmonary complications in patients with autoimmune deficiency syndrome is

high. Approximately 65% of AIDS patients develop pneumocystis carinii pneumonia.

Approximately 70% of these patients survive the first episode if treated with trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole or pentamidine. Prompt diagnosis and treatment are therefore critical. The

relapse rate is around 20% for these patients and mortality increases with successive infections.

Transbronchial biopsy and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) detect pneumocystis in 100% of AIDS

patients. Sputum inductions are effective 50% of the time in detection. Pneumococcal

pneumonia with bacteremia and tuberculosis also are increased in AIDS.

Predisposing And High Risk Factors Of Nosocomial Pneumonia:

•

Over age 65

•

HIV or AIDS

•

Kidney disease

•

Cancer

•

Organ and tissue transplantation

•

Taking immunosuppressive medications

•

Have a weak immune system from any cause

•

Acute or chronic disease such as pulmonary disease, heart disease, or diabetes

•

Intubation

•

Debilitation

•

Malnutrition

•

Alcoholism

•

Granulocytopenia

•

Recent dental procedures

•

Recent antibiotic use.2

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

13

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

DIAGNOSIS

E

PIDEMIOLOGY - Geographical data, seasonal timing and/or a history of occupational or

unusual exposures may be critical for determining etiology. A history of travel to

Southeast Asia raises the possibility of melioidosis (an infection caused by the gramnegative bacillus). Rural areas suggest exposure to zoonotic pneumonias. An important

difference between hospital and community-acquired pneumonias to note is that the former is

less likely to be pneumococci or mycoplasma. Hospital-acquired pneumonia is more likely to be

staph aureus or enteric gram-negative bacilli.

Unlike viral pneumonia, bacterial pneumonia shows little seasonal variation. An exception is

those that occur as a complication of a preceding viral infection. Influenza is typically involved,

but measles, rubella, and varicella are reported to precede beta-hemolytic streptococcus,

particularly in pediatric patients. Contact with birds suggests psittacosis and contact with wild

animals raises the possibility of tularemia or plague. A simultaneous or recent illness among the

family is not commonly seen with a bacterial pneumonia. Such a history may indicate

mycoplasma or a virus. Occupational history provides information on exposure to animals,

animal products, or specific pathogens. The latter is particularly important for lab workers.

HISTORY AND CLINICAL PRESENTATION

A

ge, underlying illnesses, and social habits predispose a patient to specific types of

pneumonia. Chlamydia trachomatis is found primarily in neonates, mycoplasma in older

children and young adults, and gram-negative bacilli predominate in the elderly.

Bacterial pneumonias increase frequently in patients with underlying medical conditions. COPD

patients are predisposed to staphylococcus pneumoniae and hemophilus influenzae infections.

Alcoholism predisposes to anaerobic lung abscess and IV drug use to bacteremic staphylococcus

pneumonia. Staphylococcus aureus is most likely the causative agent in diabetics, renal or liver

failure, influenza, cystic fibrosis, and in defects of the skin continuity. Enterobacter and

pseudomonal organisms cause lung infections in the chronically debilitated/hospitalized,

immunosuppressed, intubated, or those who have had prior broad-spectrum antibiotics. A classic

history for pneumococcal pneumonias includes the sudden onset of chills, pleuritic chest pain,

dyspnea, and rusty sputum. A classic legionella pneumonia produces diarrhea, fever, headache,

confusion and muscle pain.

The physical examination should be thorough. The exam should include looking for the

complications of pneumonia also. These include pleural effusion, pericarditis, endocarditis,

meningitis, and brain abscess. Begin with an evaluation of heart rate. Normally, the pulse

increases approximately 10 per minute for each degree (Celsius) increase in temperature. The

presence of a “bradycardia” relative to the amount of fever is associated with legionella,

psittacosis, mycoplasma and tularemia. Fever is usually present around the clock but peaks

between 6-10 PM. Pseudomonas, miliary tuberculosis, typhoid fever and brucellosis peak

between 6-10 AM. Temperature for gram-negative pneumonias are high. (Pseudomonas

infections average 103.6o F). Fever usually persists for 1-2 weeks in uncomplicated cases. The

elderly, those in shock, or who have myxedema (cretinism) may have no fever. Rigors or severe

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

14

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

shaking chills may suggest pneumococcal pneumonia more often than the other bacterial

pathogens.

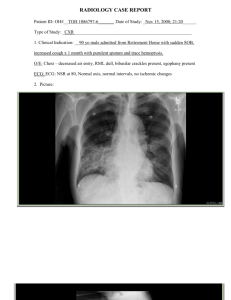

Pneumococcal Pneumonia (Right Middle Lobe)

The persistence of fever and leukocytosis with patients on appropriate antibiotics usually indicate

a complication, such as, empyema or abscess. The persistence of fever is not as important as its

slope. The peak temperature every 24 hours provides an objective measurement of the severity

of the infection. The slope over several days indicates the improvement or worsening of the

pneumonia.

Any severe pneumonia associated with necrosis of the alveoli can produce hemoptysis. It is

rarely life-threatening. Most often, the sputum is merely blood-streaked. Most cases involving

hemoptysis are a result of gram-negative organisms.

The color of the sputum provides diagnostic information. Rust-colored or blood streaked sputum

is produced by pneumococcus. Klebsiella produces brick-red, tenacious, gelatinous (currant

jelly) mucus. Staphylococcal pneumonias produce a salmon-pink or cream-colored sputum.

Pseudomonas, Haemophilus and Pneumococcus may produce green sputum. The sputum in

anaerobic infections may be foul-smelling. Influenza viruses produce blood-tinged sputum.

It is difficult to diagnose pneumonia in the severely ill. Pneumonia must be differentiated from

other conditions that cause cough, decreased blood gases, and an abnormal CXR. The

differential diagnosis includes: pulmonary embolism with infarction, adult respiratory distress

syndrome (ARDS), atelectasis, and fluid overload, to name a few. The appearance of a new

organism on the gram stain, or an increased purulence of sputum associated with a fever and

other respiratory signs, suggest a pneumonia in the critically ill. The WBC is not always helpful

in these patients. The WBC may be normal or low in some patients, such as, those on

immunosuppressive therapy or the COPD patient.

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

15

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

HISTORY

•

Character of sputum

•

Rigors and chills

•

Headache

•

Malaise

•

Nausea, vomiting and diarrhea

•

Myalgia

•

Exertional dyspnea

•

Pleuritic chest pain

•

Abdominal pain

•

Anorexia and weight loss

PHYSICAL

•

Fever

•

Tachypnea

•

Tachycardia or bradycardia

•

Cyanosis

•

Decreased breath sounds

•

Wheezes, rhonchi and rales

•

Egophony on auscultation

•

Pleural friction rub

•

Dullness to percussion

•

Altered mental status

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

16

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

LABORATORY EVALUATION

T

he WBC helps separate atypical pneumonia from the more typical bacterial pneumonia.

A normal or minimal increase in the WBC is compatible with atypical pneumonia

(mycoplasma, psittacosis, around the clock fever and nonbacterial pneumonia). There is a

marked increase in the WBC with pneumococci, Hemophilus and gram-negative bacilli.

However, overwhelming infection also can result in a lower than normal WBC (leukopenia). It

is also important to note the WBC may not rise significantly in the COPD patient with

pneumonia. Therefore, one should not rule out pneumonia in a patient, particularly one with

COPD, based upon low WBC results. Neutrophilia is the norm in bacterial pneumonias but

eosinophilia occurs in coccidioidomycosis. Legionnaires disease can cause an abnormality of

liver enzymes, electrolytes, and urinalysis.

The recovery of the pathogen is important to verify the clinical diagnosis and optimize therapy.

Specimens need to be obtained before initiation of antibiotic therapy, if possible. Blood samples

and pleural fluid specimens (if present) should be obtained on hospitalized patients. If

meningitis is a possibility, CSF fluid should be obtained. A positive culture usually establishes a

specific diagnosis. However, the yield is less than 20% for all cases of bacterial pneumonia with

the above specimens, depending upon the specific etiology. Microbiological diagnosis is usually

dependent upon recognition of the pathogen in the sputum.

Examination of expectorated sputum is the easiest and least invasive method of diagnosis.

However, there are a number of problems with expectorated sputum. They include inability to

get an adequate specimen, contamination with oral flora, and the unsuitability of the specimen

for anaerobes. The first two are minimized with careful lab screening and specimen collection

techniques.

If expectorated sputum is believed to be representative of the lower respiratory tract, it should be

gram-stained. A predominant flora may be identified when examined under 1000x

magnification.

Other procedures are used to detect specific organisms or microbial antigens. These include:

coagglutination, latex agglutination, counterimmunoelectrophoresis, the quellung reaction,

monoclonal antibody reagents and DNA probes. However, a gram stain of the sputum provides

reliable presumptive information if it is done before antibiotics are started.

A sputum culture yields definitive information, assuming the specimen is actually sputum and

has been cultured properly. Many organisms are lost if the specimen is not processed quickly,

even if refrigerated. Sputum cultures are also unreliable for anaerobes due to the profuse amount

of normal aerobic flora. Representative sputum is usually unavailable for fungal, parasitic, or

viral pneumonias. Pulmonary infections with escherichia coli, torulopsis, adenovirus, or

cytomegalo virus (CMV) often have the organism in the urine also.

In most pneumonias, the lymph nodes produce pathogen-specific IgM and IgG antibodies. IgA

is produced in cases of pharyngitis. Parasitic infections or inhaled antigens increase IgE levels.

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

17

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

A fourfold increase in antibodies to the causative organism is not unusual, usually occurring

during recovery. Rapidly fatal cases are often related to the patient’s inability to develop

adequate antibodies. Measurement of antibodies is interesting but is of limited benefit in

diagnosis of pneumonia.

Mature white blood cells leave the bone marrow in acute bacterial infections. Later, younger

leukocytes enter the circulation and cause a “shift to the left” on the differential WBC. The

aged, debilitated, alcoholics, or immunosuppressed patients fail to have a reserve of mature

leukocytes so they get a very rapid shift to the left. At the start of severe pneumonias, the

synthesis of albumin by the liver also ceases and maturation of RBC’s in bone marrow slows.

These lead to anemia and hypoalbunemia if the pneumonia persists longer than two weeks.

The initial WBC in patients with gram-negative bacterial pneumonia averages 15,000 cells/cubic

mm. The maximum is usually less than 19,000. Less than 5000 is unusual, except for the severe

alcoholic or immunosuppressed patient. Leukocytosis and a shift to the left sometimes occur

within the first 24-48 hours after the onset of viral pneumonia. A normal WBC with a relative

lymphocytosis after the first few days is the norm.

Laboratory Studies

•

Leukocytosis with a left shift (absence does not exclude a bacterial infection,

especially in the elderly)

•

Leukopenia (< 5,000)

•

Arterial blood gases (hypoxia and respiratory acidosis)

•

Culture and Gram stain pleural effusions or frank empyema fluid

•

Pulse oximetry (< 95%)

•

Sputum examination in addition to culture and gram stain

INVASIVE DIAGNOSTIC TECHNIQUES

I

nvasive techniques other than the above to diagnose pneumonia include transtracheal

aspiration (TTA), transthoracic lung aspiration (TLA), and bronchoscopy. TTA is the safest

and easiest procedure with the highest diagnostic yield. A direct sample of lower respiratory

tract secretions is made through a needle inserted into the trachea via the cricothyroid membrane.

TTA specimens are free of colonizing oral flora and are suitable for anaerobic culture.

Complications of TTA include bleeding, paratracheal and cutaneous infection, subcutaneous or

mediastinal emphysema, hypoxia, and vasovagal reactions. The overall incidence of significant

complications is low when an experienced person performs the procedure. TTA is ideally used

when oropharyngeal contamination is a problem. It is the procedure of choice for anaerobic

cultures. TTA is advantageous for those patients likely to have oral contamination with gramnegative bacilli and staph aureus, such as, hospitalized patients and alcoholics. It is also useful

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

18

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

for patients not producing sputum.

Transthoracic lung aspiration obtains a specimen directly from the lung parenchyma. TLA is a

successful method for diagnosing malignant pulmonary lesions, but is less successful for

infections. A small-bore needle is inserted between the ribs into the affected area and material is

aspirated. Those who cannot survive a total pneumothorax should not be done since this occurs

in approximately 25% of patients. Additional contraindications are bullous emphysema,

bleeding abnormalities, uncooperative patients, uncontrollable coughing, and patient’s receiving

mechanical ventilation. Complications are more frequent with TLA than with TTA. TLA is

probably the procedure of choice when pulmonary malignancy is the leading diagnosis because

of its high yield for cytological exam. It also may be the preferred invasive procedure in young

infants and children.

Bronchoscopy provides aspirated specimens of lower respiratory tract secretions or bronchial

brushings. A brush specimen increases the yield for pathogenic fungi and mycobacteria.5

Protected brush designs increase the yield further and help eliminate oropharyngeal

contamination. One needs strict attention to procedural details and quantitative culture

methodology for valid results on bronchoscopy specimens.

Invasive Diagnostic Procedures

•

Bronchoscopy

•

Transtracheal aspiration for culture

•

Thoracentesis

RADIOLOGIC EVALUATION 6

T

he chest X-ray is used to document both the presence and extent of pneumonia. Changes

are very subtle in the early stages of pneumonia. Minimal X-ray changes do not therefore

preclude the diagnosis. The location and character of the infiltrate are noted on the film.

Look for evidence of pleural effusion, cavitation, adenopathy, calcification, mediastinal shifting

and volume loss. Pneumonia as a result of aspiration is most often located in the posterior

segment of the right upper lobe or the superior segment of the right and left lower lobes. These

areas are usually dependent when aspiration occurs.

Follow-up chest X-rays are necessary to document resolution, exclude the possibility of an

underlying neoplasm, and evaluate for damage and fibrosis. The CXR may take up to 3 months

to clear completely for some pneumonias. Those with a satisfactory clinical improvement do not

need multiple, and sequential CXR’s, except for smokers older than 35 years old. They have an

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

19

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

increased risk of cancer and should continue to be followed with X-rays.

Imaging Studies

Chest X-Ray

•

Air bronchograms may be seen in S. pneumoniae.

•

Cavitary lesions and bulging lung fissures may be seen with Klebsiella pneumoniae.

•

Cavitation and associated pleural effusions are noted in Staphylococcus aureus,

anaerobic infections, gram-negative infections and tuberculosis.

•

Legionella has an affinity for the lower lung fields.

•

Klebsiella has a tendency to infect the upper lung fields.

CT Scan

•

High resolution scanning may aid in diagnosis.

Diagnosis Of Pneumonia

•

History and Clinical Presentation

travel exposure

underlying medical conditions

occupational exposure

sudden onset of fever and chills

pleuritic chest pain

dyspnea

•

Laboratory

increased WBC (in most pneumonias and patients)

cultures

anemia (prolonged illness)

hypoalbuminemia (prolonged illness)

•

Radiology

infiltrates

effusions

cavitation

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

20

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

TREATMENT

M

ost patients with bacterial pneumonia should be hospitalized. An exception is a young,

otherwise healthy individual with mycoplasma pneumonia. Other patients with no

associated hypoxemia, toxicity, underlying medical conditions, immunocompromise,

leukopenia, extrapulmonary infection, or extensive disease on the CXR also can be managed as

outpatients. The therapeutic plan for pneumonia revolves around the choice of antibiotic,

correction of reversible patient abnormalities, and general supportive care. Each of these is

discussed below.

Antibiotics – The mainstay of drug therapy for bacterial pneumonia is antibiotic treatment.

Ideally, one wishes to obtain culture specimens as a first step, if a patient is not severely ill.

However, one should not wait for extended periods to institute therapy just to get a specimen.

The choice of the therapeutic agent depends upon which bacteria is suspected. The bacteria

suspected is, in turn, based upon the clinical setting and the results of preliminary tests. Severely

ill patients should get broad-spectrum coverage for all pathogens appropriate to the clinical

setting. Those with mild to moderate illness should have therapy specifically aimed at the

predominant flora on a gram stain. For example, if gram positive elongated diplococci are seen,

give penicillin. If gram-negative pleomorphic coccobacilli (H. influenzae) are predominant, give

ampicillin or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

One needs to differentiate hospital from community-acquired infections. An atypical pneumonia

syndrome is more probable for the latter. Staph aureus, gram-negative bacilli, and pseudomonas

is more common for the former. Erythromycin is effective for most community-acquired

pneumonias with mild to moderate illness (except Chlamydia TWAR). It is seldom appropriate

for nosocomial infections. Broad-spectrum coverage for either staphylococcus or gram-negative

bacilli is more appropriate for nosocomial infection, depending upon the results of sputum gram

stains.

When the etiological bacteria has been identified, the initial regimen is changed to a specific

antibiotic. The ideal drug for a known pathogen should have the narrowest spectrum of activity,

be the most effective, least toxic, and least costly. Organisms cultured from the blood, pleural

fluid, TTA, or TLA are assumed to be the pathogen. Expectorated sputum cultures are less

reliable. They must be interpreted based upon the quality of the specimen and the clinical

impression.

Typically, staph aureus and gram-negative bacilli are easily recovered from respiratory

secretions. If they are not recovered after 24 hours of incubation, consider eliminating coverage

for them. An exception is patients who are high-risk, i.e., a patient with decreased white blood

cells. If the pathogen is not identified, re-evaluate therapy based upon patient response. A good

clinical response obviously indicates continued therapy. If a multiple-drug regimen has been

used, consider narrowing the spectrum when there is patient improvement.

Successful treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia depends upon the presence and type of

underlying disease(s), the specific causative organism, and the timeliness and appropriateness of

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

21

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

therapy. The choice of antibiotic is dependent upon gram stains and cultures, patient-specific

history of recent antibiotics, institution-specific infection rates by certain pathogens, patient drug

allergies, and underlying disease states, such as, immunosuppression.

Choice of antibiotic also depends upon the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the drug

in question. These factors affect the drugs ability to penetrate the respiratory tract. To kill a

pathogen the drug must pass through the blood vessel wall, interstitium, alveolar/airway wall,

and enter the secretions. One must get the “drug to the bug” for it to be effective. Molecular

weight, electrical charge, solubility, and many other factors affect its penetration ability.

Fluoroquinolones (Ciprofloxacin, Ofloxacin) penetrate the respiratory tract best, followed by the

cephalosporins and penicillins.

Aminoglycosides are the most effective agents against gram negative nosocomial infections.

They penetrate poorly, so high serum concentrations must be maintained. Aminoglycosides are

usually used in combination with a broad-spectrum cephalosporin or penicillin. This

combination covers both gram positive and anaerobic organisms. It also prevents development

of resistant gram-negative organisms. Institutions with high Legionella rates should add

erythromycin to the initial regimen. The duration of therapy for nosocomial pneumonia depends

upon the pathogen and patient response. Streptococcus pneumoniae should be treated for 7-10

days, hemophilus influenzae 10-14 days, staphylococcus aureus and gram-negative bacilli 14-21

days.

Summary Of Antibiotic Therapy For Bacterial Pneumonia 3,8

•

Penicillins: penicillin G, ampicillin, amoxicillin

•

Semisynthetic penicillins: oxacillin, nafcillin

•

Macrolides: Erythromycin, clarithromycin, azithromycin

•

First generation cephalosporins: cefazolin

•

Second generation cephalosporins: cefuroxime, cefamandole

•

Third generation cephalosporins: cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, ceftizoxime

•

Antipseudomonal cephalosporins: ceftazidime, cefepime

•

Quinolones: ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin

•

Tetracyclines: doxycycline

•

Carbapenems: imipenem, meropenem

•

Monobactams: aztreonam

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

22

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

•

Beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor combinations:

Ampicillin/sulbactam

Ticarcillin/clavulanate

Piperacillin/tazobactam

•

Vancomycin (Vancocin)

Depending on the type of pathogen, recommended antibiotic therapy may include just one, or a

combination of these antibiotics.

Correction Of Reversible Patient Abnormalities - Purulent collections can occur in the

mediastinum, pericardium, or peritoneum from pneumonia. Surgical drainage of such

collections is critical. Parenchymal lung abscess is not considered for surgical drainage because

it communicates with a bronchus. Undrained collections as a result of tumor, foreign bodies,

secretions, etc., can become a closed-space infection in the lung. If so, removal is necessary via

bronchoscopy, local radiation, or chemotherapy.

Excessive secretions are mobilized with chest physical therapy (CPT) for patients who have

difficulty clearing their secretions. Most patients with acute, uncomplicated, bacterial

pneumonia do not require CPT. (CPT is more appropriate for cystic fibrosis and bronchiectasis).

For those who have difficulty with secretions, aerosol treatments with bland aerosols or

acetylcysteine (Mucomyst®) to thin the mucus is of benefit. However, bland aerosol

administration has not been conclusively “proven” to be effective in thinning secretions.

Defects of the immune system predispose to infection and a slow recovery. Many defects cannot

be reversed, but drug-related suppression may be improved. Stopping the immunosuppressive

drug or tapering the dosage should be attempted, if possible. A decrease in white blood cells is

often caused by chemotherapy and is associated with antibiotic-resistant pneumonias. White

blood cell transfusions are logical, but have not been very successful to date. They may be

useful in combination with appropriate antibiotic therapy for gram-negative sepsis.

Supportive Care - Dehydration is common and may lead to electrolyte abnormalities.

Therefore, adequate hydration must be maintained. Extensive cavitary disease or persistent

empyema may cause a negative nitrogen balance so adequate nutritional and caloric intake must

be ensured with long-term illness. Most pneumonias are short-lived, so this is usually not a

problem.

The need for ventilatory support is determined by the extent of the pulmonary infection and the

state of the patient’s respiratory function. The majority of patients with pneumonia do not

require ventilatory support. Supplemental oxygen should be provided for documented hypoxia.

Routine administration of oxygen in the absence of hypoxia is not necessary.

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

23

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

Treatment Of Pneumonia

•

Antibiotics

based on culture results

severely ill: broad-spectrum coverage

mild/moderately ill: base on gram stain results

community-acquired: erythromycin

hospital-acquired: aminoglycoside with cephalosporin or

penicillin

•

Correction of reversible patient abnormalities

drainage of purulent collections

chest physical therapy

mucolytics

reverse drug-related immunosuppression

correction of electrolytes

bronchodilators for patients who manifest bronchospasm

•

Supportive care

hydration

nutrition

oxygen as necessary

mask or nasal CPAP

intubation/ventilation if indicated

COMPLICATIONS

P

ulmonary complications of bacterial pneumonia primarily consist of hypoxia and dyspnea

in the acute phase. Fibrosis may develop in the area of infection following resolution.

Cavitation may be present, particularly with gram-negative pneumonias. Malnutrition and

dehydration also can occur in the acute phase. Long-lasting pneumonias result in a reversible

debilitation. Additional complications of empyema, bacteremia, and CNS problems are

discussed in further detail below.

Empyemas develop as a result of lymph node obstruction or extension of the pneumonia across

the visceral pleura. (Lymph node obstruction causes a back flow of infected lymph into the

pleural space). Viral and mycoplasma pneumonias usually do not cause empyemas. However,

mycoplasma infections in patients with sickle-cell anemia do commonly get lobar consolidation

and effusion. Group A streptococcus, bacteroides and staphylococcal infections give empyemas

early in the infection. (The latter is almost exclusively in children). Pneumococcus, escherichia

coli, pseudomonas, and klebsiella infections may develop empyema midway through the

pneumonia.

Bacteremia is obviously a very serious complication of bacterial pneumonia. Colony counts vary

from less than 10 to 3500 bacteria per ml of blood. Obviously, the greater the number of

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

24

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

bacteria, the worse the prognosis. Prognosis also worsens with age. Septic arthritis, pericarditis,

myocarditis, endocarditis, peritonitis, empyema of the gall bladder, and disseminated

intravascular coagulation (DIC) are other complications of bacteremia.

Bacteremia can “seed” the meninges or brain with bacteria. This can lead to meningitis or brain

abscess. Meningitis is common in pneumococcus bacteremia. Bacteroides infection is

associated with brain abscess. Aseptic meningitis or encephalitis is associated with enterovirus

pneumonia in children. Serious meningoencephalitis and Guillain-Barre syndrome are

occasional complications of mycoplasma pneumonia.

Additional Complications Of Bacterial Pneumonia

•

Local destruction of lung tissue from infection with scarring

•

Bronchiectasis

•

Pulmonary abscess

•

Respiratory failure

•

ARDS

•

Ventilator dependence

•

Superinfection

•

Death

TREATMENT AND CLINICAL MANIFESTATION OF STREPTOCOCCUS AND

STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS PNEUMONIA

STREPTOCOCCUS PNEUMONIAE (PNEUMOCOCCUS) – (Typical Pneumonia)

P

neumococcus is the single most common cause of community-acquired pneumonia

requiring hospitalization. Pneumococcus infects a broad cross-section of the population

and produces a wide-spectrum of disease other than pneumonia. Pneumococcal

pneumonia develops in approximately 2 per 1000 people yearly. Its incidence is increased in

infants, the elderly, military recruits, renal and bone marrow transplants, and gold miners in

South Africa.

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

25

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

Streptococcus Pneumoniae

Pneumococcus is gram-positive cocci that appear in pairs or short chains. It possesses a complex

polysaccharide capsule that aids identification. The pneumococcus organism is recovered from

sputum in less than half of the cases. Unfortunately, it is also recovered from many patients

without infection. Therefore, there are both false-positive as well as false-negative sputum

cultures. TTA improves the yield and specificity for pneumococcal specimens. A blood culture

is positive in 20-30% of patients.

Pneumococcus is carried in the upper respiratory tract in 5-60% of asymptomatic individuals.

The highest incidence is in infants and families with children. Transmission is from person to

person, possibly through aerosol droplets or physical contact. Infections predominate in winter

and early spring months. Men are affected twice as much as women. Up to 70% of patients

have a history of a preceding upper respiratory infection (URI). The seasonal activities of

respiratory viruses therefore coincide with pneumococcal pneumonia infections.

Clinical Manifestation

The first clinical manifestation of pneumococcal pneumonia is the abrupt onset of chills followed

by a sustained fever. Repetitive shaking chills are unusual without antipyretic therapy. Within

hours, cough, dyspnea and rusty mucoid sputum is produced. Most patients develop severe

pleuritic chest pain, tachypnea, and a splinted respiratory pattern.

Pneumococcal patients appear acutely ill, agitated, cyanotic, and in respiratory distress.

Tachypnea, tachycardia, and fever are invariably present. There are early, fine crackles and

decreased breath sounds in the involved lung segments. CXR abnormalities are unilateral on the

affected side. They consist of lobar consolidation or patchy bronchopneumonia. The latter is

more common in children. Cavitation and empyema are rare. Pleural effusion develops in 2550% of patients. The physical signs of consolidation gradually evolve.

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

26

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

Leukocytosis is seen in most patients. The total WBC range is between 15,000-25,000 cells per

cubic mm. There is neutrophilia and a leftward shift on the differential count. An overwhelming

infection causes neutropenia with a count less than 3000 cells per cubic mm.

Appropriate antibiotic therapy provides a positive clinical response within 24-48 hours in

pneumococcal pneumonia. Tachypnea and tachycardia resolve gradually. Fever may persist up

to 5 days. The CXR may take 4-8 weeks to clear. Complications of pneumococcal pneumonia

are a result of spread into other areas. Empyema and purulent endocarditis are rare but require

drainage. Meningitis, endocarditis, arthritis and cellulitis also have been described. Asplenic

individuals may get fulminant septicemia and DIC. In hospitalized patients, the mortality rate is

15-20%. Mortality rate increases to greater than 50% for those more than 70 years old.

Treatment

The treatment of choice is procaine penicillin G, 600,000 units IM twice daily for 7-10 days (a

minimum of 5 afebrile days). For IV therapy, use aqueous penicillin G in a daily dosage of 2.44.8 million units. Larger doses or broader-spectrum agents should be avoided because of the

danger of superinfection and other unnecessary side-effects. Patients with significant

complications can be treated with 12-18 million units daily. If the patient has a delayed-type

penicillin allergy, cefazolin can be substituted. For significant allergy to penicillin, use

erythromycin. Chloramphenicol also can be used if meningitis is present in those with allergy.

Many strains have become resistant to various antibiotics. Resistance to penicillin now

approaches 40% for S. pneumoniae. If this is suspected, the drug of choice is vancomycin.

Sparfloxacin, a new-generation, broad-spectrum fluoroquinolone, is also useful. It has the added

advantage of being effective against other strains of penicillin-resistant pneumococci and

atypical organisms. Susceptibility testing must be performed on very sick individuals or those

not responding to therapy. The major preventive measure at the present time to pneumococcal

pneumonia is the pneumococcal vaccine. The vaccine is recommended for those who are in a

high-risk group (the elderly and those with underlying diseases).

STAPHYLOCOCCUS AUREUS - (Typical Pneumonia)

T

his organism accounts for less than 5% of community-acquired pneumonias but about

10% of hospital-acquired pneumonias. In the latter, it is usually contracted from the

bloodstream or from aspirated oral secretions. Approximately 15-30% of healthy adults

carry staph aureus in the nose. Health care workers may have a carriage rate greater than 50%.

Staphylococcus is easily transferred by hand contact.

Staphylococcus is a facultative gram-positive coccus. Gram stains are often contaminated with

oropharyngeal bacteria. Despite this, staph aureus is usually recovered in heavy growth from

sputum cultures. Less than 25% of aspiration cases are associated with a positive blood culture.

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

27

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

Staphylococcus Aureus: Chest roentgenogram of an intravenous drug abuser showing bilateral

patchy densities and pleural involvement – multiple blood cultures positive for Staphylococcus

Aureus.

Staphylococcus Aureus: Detailed view of right lower lung field showing several lesions that

have excavated forming thin-wlled abscesses.

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is a bacterial strain, which is resistant to

many antibiotics. MRSA is occurring with increased frequency, and can spread rapidly between

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

28

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

patients if proper infection-control procedures are not adhered to. As with many infections,

handwashing is the best way to prevent the spread of this bacterial strain. Vancomycin is used to

treat MRSA. Methicillin susceptible S. aureus is treated with semisynthetic penicillins such as

oxacillin or nafcillin.

Staphylococcus aureus is more likely to be found in patients with underlying pulmonary disease

and in those at risk of pneumonia. It commonly follows influenza infections and may complicate

measles infection in children. It can spread to the lungs from endocarditis or from other infected

vascular sites.

Clinical Manifestation

If the cause of staphylococcal pneumonia is from aspiration, the clinical manifestations of fever,

dyspnea, cough, and purulent sputum are present. If the cause is from the bloodstream, the

patient exhibits symptoms of endocarditis. Respiratory symptoms may be absent despite CXR

changes. The physical examination usually reveals fever, prostration, and respiratory distress.

Lobar consolidation is unusual. Crackles and decreased breath sounds are typical. Pleural

effusion, empyema, and abscess formation are common.

WBC’s greater than 15,000 cells per cubic mm, neutrophilia, and increases in band forms are

typical. If there is underlying endocarditis, there may be hematuria, anemia, abnormal renal

function, heart murmur, embolic skin lesions and heart failure. The CXR reveals multiple,

discrete, and often cavitary bilateral lesions, particularly in the lower lobes. In cases of airborne

acquisition, segmental or central consolidation is present. Abscess formation and pleural

effusion occur in 25% of cases.

Local complications of staphlyococcal pneumonia include abscess formation and empyema. In

children, staphylococcal infection is a common cause of pneumatoceles and pyopneumothorax.

Metastatic infections of the CNS, bones, joints, skin and kidneys are associated with positive

blood cultures. Sepsis and endocarditis are either a complication or an underlying cause of

staphylococcal pneumonia.

Treatment

Penicillinase-resistant penicillin (nafcillin, oxacillin) is recommended for uncomplicated cases in

doses of 8-12 grams IV per day for 10-14 days. For those with cavitation or empyema, continue

for 4-6 weeks (longer for underlying endocarditis). For those allergic to penicillin use a firstgeneration cephalosporin, and for those with an immediate-type allergy, use vancomycin.

A thoracentesis should be performed on pleural effusions that develop. Drain all empyema fluid.

If the strain is resistant to the usual penicillins use IV vancomycin, 2 grams per day. Place

hospitalized patients in total isolation to prevent its spread. Elderly and debilitated patients

should receive an influenza vaccine as a preventive measure.

This material is copyrighted by RC Educational Consulting Services, Inc. Unauthorized duplication is prohibited by law.

29

BACTERIAL PNEUMONIA

HEMOPHILUS INFLUENZAE – (Atypical Pneumonia)

H

emophilus influenzae is the major bacterial pathogen of childhood. It is recovered from

90% of children by age 5. It has been increasing in the adult population and now ranks

among the most common bacterial pneumonias requiring hospitalization. Hemophilus is

a frequent colonizer in COPD. Those with lung disease particularly asthma, young children, and

alcoholics are at the greatest risk from hemophilus.

Hemophilus Influenzae

Hemophilus is a small, thin, fastidious, gram-negative rod. It is difficult to detect by a sputum

gram stain. Cultures of expectorated sputum yield the organism in only 50% of documented

bacteremic cases. Recovery from blood specimens is more than 50%. It is occasionally

recovered from pleural fluid.

Clinical Manifestation