pubdoc_10_2031_155.doc

advertisement

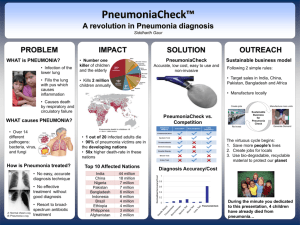

Measuring health and Disease/ The measure of health and disease is fundamental to the practice of epidemiology. A variety of measures are used to characterize the overall health of populations. Population health status is not fully measured in many parts of the world, and this lack of information poses a major challenge for epidemiologists. Defining health and disease The most ambitious definition of health is that proposed by WHO in 1948: “health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.”1 This definition – criticized because of the difficulty in defining and measuring well-being – remains an ideal. The World Health Assembly resolved in 1977 that all people should attain a level of health permitting them to lead socially and economically productive lives by the year 2000. This commitment to the “health-for-all” strategy was renewed in 1998 and again in 2003.2 Practical definitions of health and disease are needed in epidemiology, which concentrates on aspects of health that are easily measurable and amenable to improvement. Definitions of health states used by epidemiologists tend to be simple, for example, “disease present” or “disease absent” The development of criteria to establish the presence of a disease requires a definition of “normality” and “abnormality.” However, it may be difficult to define what is normal, and there is often no clear distinction between normal and abnormal, especially with regard to normally distributed continuous variables that may be associated with several diseases For example, guidelines about cut-off points for treating high blood pressure are arbitrary, as there is a continuous increase in risk of cardiovascular disease at every level A specific cut-off point for an abnormal value is based on an operational definition and not on any absolute threshold. Similar considerations apply to criteria for exposure to health hazards: for example, the guideline for a safe blood lead level would be based on judgment of the available evidence, which is likely to Diagnostic criteria Diagnostic criteria are usually based on symptoms, signs, history and test results. For example, hepatitis can be identified by the presence of antibodies in the blood; asbestosis can be identified by symptoms and signs of specific changes in lung function, radiographic demonstration of fibrosis of the lung tissue or pleural thickening, and a history of exposure to asbestos fibres. Table 2.1 shows that the diagnosis of rheumatic fever diagnosis can be made based on several manifestations of the disease,with some signs being more important than others. In some situations very simple criteria are justified. For example, the reduction of mortality due to bacterial pneumonia in children in developing countries depends on rapid detection and treatment. WHO’s casemanagement guidelines recommend that pneumonia case detection be based on clinical signs alone, without auscultation, chest radiographs or laboratory tests. The only equipment required is a watch for timing respiratory rate. The use of antibiotics for suspected pneumonia in children– based only on a physical examination – is recommended in settings where there is a high rate of bacterial pneumonia, and where a lack of resources makes it impossible to diagnose other causes.5 Likewise, a clinical case definition for AIDS in adults was developed in 1985, for use in settings with limited diagnostic resources.6 The WHO case definition for AIDS surveillance required only two major signs (weight loss ≥ 10% of body weight, chronic diarrhoea, or prolonged fever) and one minor sign (persistent cough, herpes zoster, generalized lymphadenopathy, etc). In 1993, the Centers for Disease Control defined AIDS to include all HIVinfected individuals with a CD4+ T-lymphocyte count of less than 200 per microlitre. Measuring disease frequency Several measures of disease frequency are based on the concepts of prevalence and incidence. Unfortunately, epidemiologists have not yet reached complete agreement on the definitions of terms used in this field. In this text we generally use the terms as defined in Last’s Dictionary of Epidemiology .11 Population at risk An important factor in calculating measures of disease frequency is the correct estimate of the numbers of people under study. Ideally these numbers should only include people who are potentially susceptible to the diseases being studied. For instance, men should not be included when calculating the frequency of cervical cancer