Treatment of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in an Ambulatory

advertisement

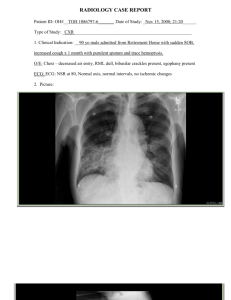

UPDATE IN OFFICE MANAGEMENT Treatment of Community-Acquired Pneumonia in an Ambulatory Setting Saira Butt, MD,a Edwin Swiatlo, MD, PhDa,b a Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, University of Mississippi Medical Center, Jackson; bVA Medical Center, Jackson, Miss. ABSTRACT Community-acquired pneumonia continues to be a significant cause of morbidity and mortality despite broad-spectrum antibiotics and advances in critical care. Frequently, the diagnosis is confounded by coexisting cardiac or pulmonary conditions. Recognition of patients at risk for complications from pneumonia is critical when making the decision of how and where to treat. This review summarizes the diagnosis and treatment of community-acquired pneumonia with oral antibiotics in an outpatient setting. Specific pathogens and clinical presentations in certain at-risk populations are highlighted. Also presented are validated algorithms for evaluating and identifying patients who may be at risk for serious complications of pneumonia and require treatment in an inpatient setting. Published by Elsevier Inc. • The American Journal of Medicine (2011) 124, 297-300 KEYWORDS: Antibiotics; Pneumonia; Vaccines Community-acquired pneumonia is diagnosed in 3 to 4 million persons annually and continues to be a leading cause of death in the United States. One study estimated that more than 900,000 cases of community-acquired pneumonia occur each year in persons aged more than 65 years.1 Approximately 80% of patients with pneumonia are treated as outpatients. Common risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia include age greater than 65 years, smoking, alcohol consumption, chronic lung diseases, mechanical obstruction of airways, aspiration of oropharyngeal or gastric contents, pulmonary edema, uremia, and malnutrition.2 CLINICAL PRESENTATION Typical bacterial pathogens such as Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus), Haemophilus influenzae, and enteric gram-negative organisms usually manifest acutely with high fever, chills, tachypnea, tachycardia, and productive Funding: Department of Medicine, University of Mississippi Medical Center and Department of Veterans Affairs. Conflict of Interest: None. Authorship: All authors had access to the data and played a role in writing this manuscript. Reprint requests should be addressed to Edwin Swiatlo, MD, PhD, VA Medical Center Research (151), 1500 Woodrow Wilson Drive, Jackson, MS 39216. E-mail address: Edwin.swiatlo@va.gov. 0002-9343/$ -see front matter Published by Elsevier Inc. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.06.027 cough. In contrast, “atypical” pathogens such as Mycoplasma, Chlamydophila, and viruses often present with fever, nonproductive cough, and constitutional symptoms that develop over days. Legionella initially may produce primarily gastrointestinal symptoms. A careful history, including travel, animal exposure, incarceration, asplenia, human immunodeficiency virus, and other comorbidities, can often suggest an otherwise unsuspected pathogen. Systemic physical findings in pneumonia are nonspecific and include fever/chills, fatigue, myalgias, or headaches. Pulmonary findings in pneumonia are typically localized to a specific lung zone and may include rales, rhonchi, bronchial breath sounds, dullness, increased fremitus, and egophony. Atypical pneumonia may have absent or diffuse findings on lung examination. Rapid progression of disease from mild, nonspecific symptoms to respiratory failure can be seen in severe pneumococcal, staphylococcal, or Legionella pneumonia.3,4 The age of the patient has important implications in disease presentation. Older patients often have humoral or cellular immunodeficiencies as a result of underlying diseases, immunosuppressive medications, or the aging process. Older patients with pneumonia have fewer symptoms than do younger patients, and mental status changes are commonly the predominant presenting symptom. Delirium may be the only manifestation of pneumonia in these pa- 298 tients. Alcoholism, asthma, immunosuppression, and age ⬎ 70 years are risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly. Among nursing home residents, advanced age, male sex, dysphagia, inability to take oral medications, profound disability, bedridden state, and urinary incontinence are risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia. Aspiration pneumonia is underdiagnosed in this group of patients, and tuberculosis always should be considered.5 Extrapulmonary physical findings can provide clues to the diagnosis. Poor dentition and foul-smelling sputum may indicate the presence of a lung abscess with anaerobic bacteria. Bullous myringitis can accompany infection with Mycoplasma pneumoniae. An absent gag reflex or altered sensorium raises the possibility of aspiration and polymicrobial infection with anaerobes. Encephalitis can complicate pneumonia caused by M. pneumoniae or Legionella pneumophila. Cutaneous manifestations of infection can include erythema multiforme (especially M. pneumoniae), erythema nodosum (Chlamydophila pneumoniae or Mycobacterium tuberculosis), or ecthyma gangrenosum (Pseudomonas aeruginosa). LABORATORY DATA Diagnostic tests such as sputum and blood cultures are optional for an etiologic diagnosis in outpatients with community-acquired pneumonia. Nasopharyngeal swabs should be collected for influenza during the appropriate season or when influenza is circulating in the community. Patients with cough for more than 1 month, chronic fever, night sweats, weight loss, or a suggestive chest X-ray should be evaluated for M. tuberculosis. A high level of suspicion is necessary to diagnose infections caused by agents of bioterrorism.6 RADIOGRAPHY The cornerstone of diagnosis is the chest X-ray, which usually reveals an infiltrate at presentation. However, this finding may be absent in dehydrated or neutropenic patients. Also, the radiographic manifestations of chronic diseases such as congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and malignancy may obscure the infiltrate of pneumonia.7 Although radiographic patterns are usually nonspecific, they can sometimes suggest a microbiological diagnosis. Focal consolidation is seen in typical bacterial pneumonia, whereas viruses, Mycoplasma, and Chlamydophila frequently present with an interstitial pattern. Cavitary lesions may be associated with bacterial abscesses, fungi, or Nocardia. Rapid progression with multifocal lung involvement may indicate Legionella, S. pneumoniae, or Staphylococcus aureus.8 MANAGEMENT Choosing the site of care for community-acquired pneumonia is the single most important decision made by clinicians. The American Journal of Medicine, Vol 124, No 4, April 2011 Table 1 Pneumonia Severity Index Points Demographic factors Age for men Age for women Nursing home resident Coexisting illnesses Active neoplastic disease Chronic liver disease CHF Cerebrovascular disease Chronic renal disease Physical examination Altered mental status Respiratory rate ⬎ 30 Blood pressure ⬍ 90 mm Hg Temperature ⬍ 35°C or ⱖ 40°C Pulse ⱖ 125 bpm Laboratory and radiographic findings Arterial pH ⬍ 7.35 BUN ⱖ 30 mg/dL Sodium ⬍ 130 mmol/L Glucose ⱖ 250 mg/dL Hematocrit ⬍ 30% PaO2 ⬍ 60 mm Hg Pleural effusion CHF ⫽ congestive heart failure; BUN ⫽ blood PaO2 ⫽ partial pressure of arterial oxygen. Age (y) Age (y) ⫺10 ⫹10 ⫹30 ⫹20 ⫹10 ⫹10 ⫹10 ⫹20 ⫹20 ⫹20 ⫹15 ⫹10 ⫹30 ⫹20 ⫹20 ⫹10 ⫹10 ⫹10 ⫹10 urea nitrogen; This decision involves 3 steps: determination of disease severity, assessment of any preexisting social conditions that compromise the safety of home care, and clinical judgment. The Pneumonia Severity Index assesses 20 variables (Table 1) and places patients into 5 risk groups that can help to stratify patients for therapeutic and prognostic purposes.9 Patients in groups I and II can be treated as outpatients, patients in group III can be treated with a short hospitalization or in observational units, and patients in groups IV and V should be treated as inpatients. A more tractable model for community-acquired pneumonia severity assessment is CURB-65.9 The CURB-65 score is based on 5 easily measurable factors (1 point for each) from which its name is derived: confusion (based on a specific mental test or new disorientation to person, place, or time); blood urea nitrogen ⬎ 20 mg/dL; respiratory rate ⬎ 30 breaths/min; blood pressure (systolic ⬍ 90 mm Hg or diastolic ⬍ 60 mm Hg); and age ⬎ 65 years. Patients with a CURB-65 score of 0 to 1 can generally be treated as outpatients, those with a score of 2 should be admitted to the hospital, and those with a score of 3 or more are candidates for an intensive care unit.10 In addition to medical criteria, residential status also influences treatment decisions. Residents of chronic care facilities, homeless persons, and incarcerated persons are more likely to be admitted than other patients with similar severity scores. Outpatient therapy is preferred because Butt and Swiatlo Community-acquired Pneumonia Table 2 Recommended Empirical Antibiotics for Outpatient Therapy of Community-Acquired Pneumonia1 Previously healthy, no recent (within 3 mo) antibiotic therapy: macrolide OR doxycycline Previously healthy, antibiotics within past 3 mo: azithromycin or clarithromycin, PLUS high-dose amoxicillin (4 g/d) or amoxicillin-clavulanate (4 g/d); OR a respiratory fluoroquinolone alone Comorbidities (COPD, diabetes, renal or congestive heart failure, malignancy), no recent antibiotic therapy: azithromycin or clarithromycin; OR a respiratory fluoroquinolone alone Comorbidities, antibiotics within past 3 mo: azithromycin or clarithromycin, PLUS high-dose amoxicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanate, cefpodoxime, cefprozil, or cefuroxime; OR a respiratory fluoroquinolone COPD ⫽ chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. this is associated with faster return to normal activities than inpatient treatment.10 ANTIBIOTICS Antimicrobial therapy is a critical component of treatment of community-acquired pneumonia in the outpatient setting. Until better diagnostic tests are available, initial treatment remains largely empiric. Antibiotics recommended on the basis of risk factors and likely pathogens have been published recently and are summarized in Table 2.1 Presently, macrolides remain effective for patients with mild to moderately severe community-acquired pneumonia with no risk factors. Patients with chronic obstructive lung disease who have not received antibiotics or oral steroids during the previous 3 months can be treated in a manner identical to that of patients without modifying factors, with the caveat that only a newer macrolide (azithromycin or clarithromycin) be used to ensure adequate coverage of H. influenzae. Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder and a history of use of antibiotics or oral steroids within the past 3 months may have an increased risk for infection with H. influenzae and enteric gram-negative bacilli, in addition to pneumococcus, C. pneumoniae, and L. pneumophila, and a “respiratory” fluoroquinolone is recommended. A respiratory fluoroquinolone is one with predictable activity against pneumococcus, such as levofloxacin or moxifloxacin. Fluoroquinolones also are recommended if first-line therapy fails in the patient, the patient has confirmed allergy to first-line agents, or when highly resistant pneumococcus (penicillin minimum inhibitory concentration ⬎ 4 g/mL) is prevalent. For patients who can be treated in the nursing home setting and do not require hospitalization, a respiratory fluoroquinolone or amoxicillin-clavulanate plus a macrolide is recommended as the first choice. A second-generation cephalosporin plus a macrolide is an alternative. 299 Anaerobic coverage should be considered for those patients with a history of loss of consciousness or in persons with gingival or esophageal disease. Antibiotic selection should always consider local epidemiology and susceptibility patterns. FOLLOW-UP Patients treated in the outpatient setting must be monitored carefully to ensure adherence to the antibiotic regimen and clinical improvement. Follow-up by telephone or a clinic visit within 48 to 72 hours is strongly suggested. Patients who fail to respond despite what seems to be an appropriate choice of antimicrobial therapy may have complications of pneumonia, such as empyema, bronchial obstruction, extrapulmonary spread of infection, superinfections, or misdiagnosis of noninfectious causes (eg, congestive heart failure, neoplasm, vasculitis, sarcoidosis, drug reaction, alveolitis, pulmonary embolism, or hemorrhage). PREVENTION All persons aged more than 6 months should receive inactivated influenza vaccine yearly as recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.11 Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine is recommended for all persons aged more than 65 years and anyone aged 2 to 64 years with a chronic health problem, such as heart disease, lung disease, sickle cell disease, diabetes, alcoholism, and cirrhosis. All persons aged 2 to 64 years who have an immunosuppressive condition, such as hematologic malignancy, kidney failure, nephrotic syndrome, human immunodeficiency virus infection, asplenia, or organ transplant, should receive vaccine. Anyone aged more than 2 years who lives in an institutional or group setting is a candidate for pneumococcal vaccine. A comprehensive discussion of risk factors for invasive pneumococcal infection is published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.12 References 1. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27. 2. Almirall J, Bolibar I, Balanzo X, Gonzalez CA. Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in adults: a population-based casecontrol study. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:349. 3. Rubinstein E, Kollef MH, Nathwani D. Pneumonia caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(Suppl 5):S378. 4. Marrie TJ. Community-acquired pneumonia in the elderly. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:1066-1078. 5. Craven DE, Palladino R, McQuillen DP. Healthcare-associated pneumonia in adults: management principles to improve outcomes. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2004;18:939. 6. Hopstaken RM, Witbraad T, van Engelshoven JM, Dinant GJ. Interobserver variation in the interpretation of chest radiographs for pneumonia in community-acquired lower respiratory tract infections. Clin Radiol. 2004;59:743. 300 7. Houck PM, Bratzler DW, Nsa W, Ma A, Bartlett JG. Timing of antibiotic administration and outcomes for Medicare patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med 2004;164:637-644. 8. Fine MJ, Hough LJ, Medsger AR, et al. The hospital admission decision for patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:36. 9. Lim WS, van der Eerden MM, Laing R, et al. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax. 2003;58:377. The American Journal of Medicine, Vol 124, No 4, April 2011 10. Labarere J, Stone RA, Obrosky DS, et al. Comparison of outcomes for low-risk outpatients and inpatients with pneumonia. Chest. 2007;131: 480. 11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing seasonal flu with vaccination. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/protect/ preventing.htm. Accessed March 1, 2010. 12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pneumococcal vaccination. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd-vac/pneumo. Accessed March 3, 2010.