Journal of Vacation Marketing

advertisement

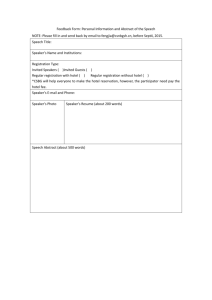

Journal ofhttp://jvm.sagepub.com/ Vacation Marketing Developing a service quality questionnaire for the hotel industry in Mauritius Rooma Roshnee Ramsaran-Fowdar Journal of Vacation Marketing 2007 13: 19 DOI: 10.1177/1356766706071203 The online version of this article can be found at: http://jvm.sagepub.com/content/13/1/19 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Journal of Vacation Marketing can be found at: Email Alerts: http://jvm.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://jvm.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://jvm.sagepub.com/content/13/1/19.refs.html >> Version of Record - Dec 14, 2006 What is This? Downloaded from jvm.sagepub.com at Universiti Teknologi Malaysia on May 6, 2012 Journal of Vacation Marketing Volume 13 Number 1 Developing a service quality questionnaire for the hotel industry in Mauritius Rooma Roshnee Ramsaran-Fowdar Received (in revised form): July 2006 Anonymously refereed paper Faculty of Law and Management, University of Mauritius, Reduit, Mauritius Tel: 230 454 1041; Fax: 230 465 6906; E-mail: rooma@uom.ac.mu Rooma Roshnee Ramsaran-Fowdar is a senior lecturer in Marketing and Management and has been working at the University of Mauritius for eight years. Her main areas of interest include business-to-business marketing, marketing of services and marketing research. ABSTRACT KEYWORDS: hotel customers, in-depth interviews, questionnaire, Mauritius, service quality, SERVQUAL, tourist satisfaction The evaluation of customer satisfaction is a primary goal for any service firm that would like to survive in this increasingly competitive market. Keeping tourists satisfied and delighted is even more important for the Mauritian tourism industry given that the destination faces fierce competition abroad. Developing a measure of hotel service quality is an important precursor to attracting and retaining tourists and hence ensuring the survival of hotels. SERVQUAL has been proposed as a generic measure of service quality that may be applicable to hotel services. The purpose of this study is to investigate whether SERVQUAL dimensions are pertinent to the hotel industry. Results from this study verify SERVQUAL dimensions, but demonstrate additional dimensions that are specific to the hotel sector. INTRODUCTION Tourism is said to be the fastest growing industry in the world over the past 50 years with no signs of slowing down in the 21st century. Apart from a country’s beautiful natural environment, the warmth of the local population, and political and economic stability, tourists’ memorable souvenirs are deeply influenced by the type of service that they receive at the hotel in which they lodge. Therefore, hotels have to strive to deliver to their guests, not only their products and services, but also ‘quality’ and ‘satisfaction’ that may lead to long-lasting survival and profitability. Quality is the cornerstone for success in any business and is perceived as a key factor in acquiring and sustaining competitive advantage.1–2 Many studies have shown that quality service increases market shares, provides greater return on investment and lowers production costs.3–6 Providing quality service improves satisfaction of customers and this is believed to lead to increased international visitation, repeat purchases of the same tourist products, customer loyalty and relationship commitment. Moreover, highly satisfied tourists spread positive word-of-mouth and in effect become walking, talking advertisements for providers whose service has pleased them, thus lowering the cost of attracting new customers. Also, highly satisfied customers may be more forgiving. Someone who has enjoyed good service in the past is more likely to believe that a service failure is a deviation from the norm. Hence it may take more than one unsatisfactory incident for Downloaded from jvm.sagepub.com at Universiti Teknologi Malaysia on May 6, 2012 Journal of Vacation Marketing Vol. 13 No. 1, 2007, pp. 19–27 & SAGE Publications London, Thousand Oaks, CA, and New Delhi. www.sagepublications.com DOI: 10.1177/1356766706071203 Page 19 Developing a service quality questionnaire in Mauritius loyal customers to change their perceptions and consider switching to an alternative service provider. Additionally, companies which command high customer satisfaction ratings also seem to have the ability to insulate themselves from competitive pressures – particularly price competition.7 Customers are often willing to pay more to stay with a firm that meets their needs than to take the risk associated with moving to a lower-priced service provider. On the other hand, tourist dissatisfaction and low service quality may lead to unfavourable behavioural intentions, such as spreading negative comments about the service provider or even destination, changing destination for their holidays, complaining and redress seeking.8–9 Therefore, hotel operators have much to gain if they can understand tourists’ expectations of them since this would assist them in serving their customers in a better way. Despite the notable progress in the lodging industry and the substantial demand for research, service quality has remained underresearched to date in the area of tourism. This study therefore aims to provide a service quality framework for the hotel industry. More specifically, the research examines attributes tourists use to evaluate the quality of service provided by their hotels. This information would not only be useful to hospitality and marketing strategists, but also to governments and commercial sectors to which the tourism industry is of much significance. The article first traces previous service quality research in the area of lodging and hospitality. This is then followed by a section of the methodology employed to gather data. The discussion section describes the findings and the final part of the article is devoted to a summary of strategic implications and suggestions for future research. BACKGROUND In this study, the term ‘service quality’ is to be interpreted to mean ‘the quality possessed by both products and service activities that are provided by a service organization to its customers’. Different theoretical perspectives on service quality were developed during Page 20 the 1980s. Gröonroos10 distinguished two types of service quality: technical and functional quality. Technical quality refers to the delivery of the core service or outcome of the service (i.e. what is offered and received), while functional quality refers to the service delivery process, or the way in which the customer receives the service (i.e. how the service is offered and received). Lehtinen and Lehtinen11 discussed three distinct service quality dimensions: physical quality, interactive quality and corporate quality. Physical quality includes the physical aspects associated with the service such as the reception area and equipment. Interactive quality involves the interaction between the customer and the service personnel, while corporate quality includes the firm’s image or reputation. From these earlier writings, it can be seen that the notion of service quality arises from a comparison of what the customers feel a seller should offer (i.e. customers’ expectations) with the sellers’ actual service performance.12 This idea was supported by an exploratory research conducted by Parsuraman et al.13 with 12 focus groups of consumers in four service industries (retail banking, telecommunications, securities brokerage, product repair and maintenance). On the basis of this study, Parsuraman et al. defined service quality as an overall evaluation, similar to, but not the same as, an attitude and refers to the degree and direction of discrepancy between customers’ perceptions and expectations. They also developed the SERVQUAL scale, an instrument which included five main service quality dimensions: tangibles (appearance of physical elements), reliability (ability to perform the promised service dependably and accurately), responsiveness (promptness and helpfulness), assurance (courtesy, credibility, competence) and empathy (easy access, good communications and customer understanding). Within each dimension, there were several items measured on a seven-point scale ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’ for a total of 22 items. Since its inception, the SERVQUAL scale has been widely used by both academics and Downloaded from jvm.sagepub.com at Universiti Teknologi Malaysia on May 6, 2012 Ramsaran-Fowdar practicing managers across industries in various countries. Though SERVQUAL has been generally robust as a measure of service quality, the instrument has been criticized on conceptual and methodological grounds. One of the main problems mentioned in the literature is the applicability of the five SERVQUAL dimensions to different service settings. Replication studies done by other investigators failed to support the fivedimensional factor structure as was obtained by Parsuraman et al.14–15 in their development of SERVQUAL. For example, McDougall and Levesque’s study16 did not support Parsuraman et al’s (1985) contention that service quality is comprised of five dimensions. They revealed only the following three underlying dimensions of service quality: tangibles, contractual performance (outcome) and customer-employee relationships (process). Moreover, research has indicated the possibility of two (Babakus and Boller17 – in a public utility sector) to nine (Carman18 – in a dental school patient clinic, business school placement centre and acute care hospital) distinct dimensions underlying the service quality construct. Babakus and Mangold19 argue that the instability of the dimensionality of SERVQUAL is probably due to the type of service sector under investigation. Parsuraman et al.20 concede though that the universality of the five dimensional structure of service quality remains in doubt and should be further researched. Only a few studies have directly applied the service quality paradigms within the context of the hospitality industry.21–5 For instance, Saleh and Ryan26 applied the SERVQUAL model27 to lodging services to test the five service quality gaps proposed by the gap model28 and the dimensionality of the SERVQUAL model as applied to hotel services. They used 33 attributes of hotel services identified in earlier lodging studies rather than the 22 items included in the original SERVQUAL model. Their findings confirmed the existence of the gaps in hotel services, but failed to identify the five service dimensions suggested by SERVQUAL. Getty and Thompson29 proposed a perform- ance-based measurement model (LODGQUAL) for lodging research. Although this proposal was new to the lodging industry, a similar performance-based service quality model (SERVPERF) was already proposed by Cronin and Taylor30 for services research. Although they justified the use of their model in the lodging industry, their scale development procedure must be taken cautiously. For example, the retrospective performance evaluations (obtained through a recall method), the use of student subjects, and their proposed dimensionality of lodging services may not generalize highly differentiated lodging products. Therefore, research indicated that perceived service quality is contingent upon the type of service offering. This implies that one generic measure of service quality is inappropriate for all services. Previous studies have shown that SERVQUAL does not cover all dimensions of hotel services that are important to guests. Since qualitative research about the quality of lodging services has been somewhat scarce, this research is therefore aimed at finding out the following: • What are the attributes on the basis of which hotel guests evaluate the quality of service provided by hotels? • Can SERVQUAL dimensions be replicated in the hotel industry or should additional dimensions be included in the service quality construct? • What instrument will help hotel managers measure service quality, monitor and improve their service and competitiveness? Service perceptions have still not received enough research attention in the area of tourism. The present study is therefore an effort to analyse tourists’ perceptions of services provided by hotel operators. Defining service quality and providing techniques for its measurement is a major concern of service providers and researchers. This becomes a particularly complex issue in a high contact service industry such as tourism and hospitality. Downloaded from jvm.sagepub.com at Universiti Teknologi Malaysia on May 6, 2012 Page 21 Developing a service quality questionnaire in Mauritius THE TOURISM AND HOSPITALITY INDUSTRY IN MAURITIUS The tourism industry is the third pillar of the Mauritian economy, after the manufacturing sector and agriculture sectors and has been a key factor in the overall development of the country. In the past two decades, tourist arrivals increased at an average annual rate of 9 per cent with a corresponding increase of about 21 per cent in tourism receipts. Tourist arrivals have been expanding significantly rising from 102,510 in 1977 to 656,453 in 2000, a more than six-fold increase. Europe has long been the widest market with tourist arrivals (67 percent) originating mainly from France, UK, Germany, Italy, Switzerland and Belgium. Africa is the second major market and is dominated by tourists from Reunion Island and South Africa. The challenges that face the Mauritian tourism sector in the years ahead are both vast and demanding if it is to maintain its status as an exclusive destination. At a time when world events – for example, wars, SARS and terrorism acts – impact so dramatically on international travel and have such a profound effect on a destination’s appeal, it is more important now than at any time in the past to ensure that all players who are involved in tourism have a common vision for the future, and are in total synergy with their collective endeavours. This will offer the dynamic industry the opportunity to perform at its optimum level and position Mauritius so that it is able to compete to its greatest advantage in the market place. Reinforcing Mauritius’ image as an exotic holiday destination to attract the discerning traveller and achieve continued growth is essential. Apart from governmental attempts to promote Mauritius, the hotel industry has also made its contribution towards the improvement of the quality of service to meet with international quality standards.31–2 Some hotels have initiated quality programmes and have been accredited with the ISO 9000 certification and others are in the process towards achieving this goal. Despite these initiatives, however, a number of tourists remain dissatisfied and complain about high Page 22 food and beverage prices, poor language and communication ability of personnel and a limited variety of food being served.33 Studies conducted on service quality issues in hotels of Mauritius are of little help because they do not provide detailed evidence on the evaluation of service quality from the perspectives of guests.34 Therefore, this study will contribute to the literature by providing qualitative evidence on customers’ expectations of service quality from hotels and this will help tailor a service quality measurement tool for the hotel industry as a whole. METHODOLOGY This article represents an exploratory effort in understanding hotel service quality in the Mauritian context. This was an important driver as there was scant literature related to service quality of hotels in Mauritius. Moreover, the SERVQUAL model had been tested in settings other than the hospitality industry.35 In-depth interviews were conducted with 32 tourists over a period of two months to probe into their needs and the services they hoped to obtain from their hotels. A convenience sample was used by choosing tourists visiting tourist villages in the different parts of the island. Tourists who were approached were first asked some preliminary questions about their background and profile and it was ensured that the respondents included in the study were chosen in such a way as to achieve diversity in terms of age, gender, country of origin, occupational status and marital status. Only those tourists who had travelled to Mauritius on vacational purposes were interviewed. Each respondent was subjected to a set of open-ended questions on their expectations of service quality provided by hotels. For example, questions asked during those unstructured interviews included: ‘What do you expect from an excellent hotel?’; ‘How do you know you are receiving a high level of hotel service?’; ‘Which criteria do you consider when choosing a hotel?’; ‘Which variables affect your satisfaction with a hotel?’; ‘What makes a hotel’s service excellent?’; ‘Why do you think no one patronises Downloaded from jvm.sagepub.com at Universiti Teknologi Malaysia on May 6, 2012 Ramsaran-Fowdar some hotels, while others have very high occupancy rates?’. Respondents were asked general questions about service quality and the responses obtained were grouped judgementally into different dimensions of service quality. Respondents had to come up with their own ideas about service quality and were deliberately not exposed to items from the SERVQUAL model. Each interview lasted for about 45 minutes to one hour and subjects were encouraged to respond freely in their own words. Detailed notes were taken during the interviews and these were eventually compiled into a report. The respondents were thanked for their time and kind co-operation with a souvenir token from Mauritius. CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS Table 1 compares the SERVQUAL dimensions to the items generated from the indepth interviews. Two additional quality dimensions were found, namely ‘core hotel benefits’ and ‘hotel technologies’ and a few additional items within each of the generic quality dimensions. When asked about their expectations from a good hotel, most respondents immediately stated that they wanted a comfortable and relaxed stay with quality food, extra amenities in rooms and recreational facilities. The core service was therefore the most important quality attribute for hotel guests and this is not represented in the SERVQUAL instrument. Moreover, hotel customers laid a lot of emphasis on the tangible environment in particular hotel and room décor and cleanliness. Guests were also demanding regarding reliability and promptness of service and consistent courtesy of staff. Younger customers made comments regarding the paucity of internet access in hotels. In this respect, Mauritian hotels were still lagging behind in terms of technological facilities. The results of this study indicate that dimensions in SERVQUAL cannot be replicated fully to the hotel industry. Other dimensions such as ‘core benefits’ (including a comfortable, relaxed and welcome feeling, variety/quality of food and recreational facilities and provision of evening entertainment, among others) and ‘hotel technologies’ (including access to telephone, television, e-mail, online reservation and international calling facilities among others) may emerge as equally critical when determining the attributes that customers use to evaluate hotel service quality. Hotel managers should take these key quality dimensions into account when assessing the level of the service they provide. Ensuring quality would eventually lead to growth of their clientele. Ways of achieving quality service could include the administration of hotel customers satisfaction surveys using the service quality dimensions involved; the improvement of the level of service performance where needed by filling the gaps and the management of expectations regarding quality of service. Another managerial implication includes the need for hotels to develop human resource management strategies to recruit and train employees to become skilful in their jobs, have excellent interpersonal skills, be courteous, friendly and competent and be empowered to be able to meet customer needs and solve their problems. Hotel managers should also pay a lot of attention to hotel décor, cleanliness and comfort of rooms, quality and variety of food served and provide basic guest room facilities such as soap, shampoo, tea, coffee, kettle, and so forth. In addition, staff should not make any errors in computing bills and should provide accurate information and service when requested. Furthermore, hotel managers should now realise the potential of the technology for the hotel industry. The changing lifestyles of customers imply that the hotel industry should make creative and innovative use of technology to enhance the value of its service offerings. This research is only exploratory and needs further validation to finally develop a reliable scale for measurement of service quality in the hotel industry. The results from this study may not be replicable outside Mauritius. Despite these limitations, however, the results provide some interesting findings and there is now enough Downloaded from jvm.sagepub.com at Universiti Teknologi Malaysia on May 6, 2012 Page 23 Developing a service quality questionnaire in Mauritius Table 1: Service quality attributes SERVQUAL dimensions (Parsuraman et al. (1985)) Quality attributes in the hotel industry* Tangibility (physical facilities, equipment and appearance of personnel) 1. Modern-looking equipment 2. Visually appealing facilities 3. Visually appealing materials 4. Neat appearance of employees Tangibility (physical facilities, equipment and appearance of personnel) 1. Modern and comfortable furniture 2. Appealing interior and exterior hotel décor 3. Attractive lobby 4. Cleanliness and comfort of rooms 5. Spaciousness of rooms 6. Hygienic bathrooms and toilets 7. Convenient hotel location 8. Neat and professional appearance of staff 9. Availability of swimming pool, sauna and gym 10. Complimentary items 11. Provision of clean beaches 12. Provision of beach facilities (beach mattresses, umbrellas, beach towels, etc.) 13. Visually appealing brochures, pamphlets, etc. 14. Availability of non-smoking areas in restaurants 15. Image of the hotel Reliability (ability to perform the expected service dependably and accurately) 1. Delivery of promises 2. Dependability in handling the customers’ problems 3. Correct performance of the service the first time 4. Maintenance of error-free records 5. Delivery of services at the time promised Reliability (ability to perform the expected service dependably and accurately) 1. Staff performing services right the first time 2. Performing the services at the time promised 3. Well-trained and knowledgeable staff 4. Experienced staff 5. Staff with good communication skills 6. Accuracy in billing 7. Accuracy of food orders 8. Accurate information about hotel services 9. Advance and accurate information about prices 10. Timely housekeeping services 11. Availability of transport facilities 12. Reliable message service Responsiveness (willingness to help customers and provide prompt service) 1. Keeping customers informed about when the service will be performed 2. Providing prompt service to customers 3. Willingness to help customers 4. Responsiveness to customers’ requests Responsiveness (willingness to provide prompt service) 1. Willingness of staff to provide help promptly Assurance (courtesy and knowledge of staff and their ability to inspire trust and confidence) 1. Courteous staff 2. Ability of staff to instill confidence in customers 3. Making customers feel safe in their transactions 4. Knowledgeable staff to answer customer questions 2. Availability of staff to provide service 3. Quick check-in and check-out 4. Prompt breakfast service Assurance (courtesy displayed by hotel staff and their ability to inspire trust and confidence) 1. Friendliness of staff 2. Courteous employees 3. Ability of staff to instill confidence in customers (continued) Page 24 Downloaded from jvm.sagepub.com at Universiti Teknologi Malaysia on May 6, 2012 Ramsaran-Fowdar Table 1: (continued) SERVQUAL dimensions (Parsuraman et al. (1985)) Quality attributes in the hotel industry* Empathy (caring, individualized attention provided to customers) 1. Understanding the customers’ requirements 2. Providing customers with individual attention 3. Convenient operating hours 4. Dealing with customers in a caring fashion 5. Having the customers’ best interest at heart Empathy (caring, individualized attention provided to guests by hotel staff) 1. Giving special attention to the customer 2. Recognizing the hotel customer 3. Calling the customer by name 4. Availability of room service 5. Understanding the customers’ requirements 6. Listening carefully to complaints 7. Problem-solving abilities of staff 8. Hotel to have customers’ best interest at heart 9. Customer loyalty programme Core hotel benefits (the central aspects of the service: benefits to hotel customers) 1. Comfortable, relaxed and welcome feeling 2. Quietness of rooms 3. Variety/quality of sports and recreational facilities 4. Security of room 5. Security and safety at the hotel 6. Comfortable and clean mattress, pillow, bed sheets and covers 7. Reasonable room rates 8. Variety of basic products and services offered (toothpaste, soap, shampoo, towels, toilet paper, stationery, laundry, ironing, tea, coffee, drinking water) 9. Guest room items in working order (kettle, airconditioning, lighting, toilet, fridge, etc.) 10. Quality of food in restaurant 11. Reasonable restaurant/bar prices 12. Choice of menus, buffet, beverages and wines 13. Provision of children’s facilities (playground, baby-sitting, swimming pool, etc.) 14. Provision of evening entertainment Hotel technologies (technological services available to hotel guests) 1. In-room technologies (telephone, voicemail, ondemand PC, television, internet plug, meal ordering, email, wake-up system) 2. Hotel technologies (online reservation, email, internet, fax, international calling facilities, hotel website, direct hotel email, computerized feedback form, special promotions on hotel website, acceptance of credit and debit cards) * Items are grouped judgementally and not through statistical processes like factor analysis Downloaded from jvm.sagepub.com at Universiti Teknologi Malaysia on May 6, 2012 Page 25 Developing a service quality questionnaire in Mauritius evidence to indicate that additional dimensions need to be included if the SERVQUAL measure is implemented in the hotel industry. REFERENCES (1) Hampton, G. M. (1993) ‘Gap Analysis of College Student Satisfaction as a Measure of Professional Service Quality’, Journal of Professional Services Marketing 9(1): 115–28. (2) Shearden, W.A. (1988) ‘Gaining the Service Quality Advantage’, Journal of Business Strategy 9(2): 45–8. (3) Garvin, D.A. (1983), ‘Quality in the Line’, Harvard Business Review 61(5): 65–73. (4) Mueller, G. and Bedwell, D. (1993) ‘Customer Service and Service Quality’, in E. Shewing (ed.) ‘The Service Quality Handbook’, pp. 459–62. New York: AMACOM. (5) Phillips, L. W., Chang, D. R. and Buzzell, R. D. (1983) ‘Product Quality, Cost Position and Business Performance: A Test of Some Key Hypotheses’, Journal of Marketing 47(2): 26–43. (6) Reichheld, F. and Sasser, W. (1990), ‘Zero Defections: Quality Comes to Services’, Harvard Business Review 69(5): 105–11. (7) Hoffman, K. D. and Bateson, J. E. G. (1997) Essentials of Services Marketing. Fort Worth, TX: The Dryden Press. (8) Pearce, P. L. (1988) The Ulysses Factor: Evaluating Visitors in Tourist Settings. New York: Pringer Verlag. (9) Zeithaml, V. A. and Bitner, M. J. (2000) Services Marketing: Integrating Customer Focus Across the Firm. 2nd edn. Boston: McGrawHill. (10) Gröonroos, C. (1982) Strategic Management and Marketing in the Service Sector. Helsinki: Swedish School of Economic and Business Administration. (11) Lehtinen, U. and Lehtinen, J. R. (1982) ‘Service Quality: A Study of Quality Dimensions’, unpublished research report, Science Management Group, OY, Finland. (12) Parsuraman, A. (2000) ‘Superior Customer Service and Marketing Excellence: Two Sides of the Same Success Coin’, Vikalpa 25(3): 3–13. (13) Parsuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A. and Berry, L. L. (1985) ‘A Conceptual Model of Service Quality and its Implications for Future Page 26 (14) (15) (16) (17) (18) (19) (20) (21) (22) (23) (24) Research’, Journal of Marketing 49(Fall): 41–50. Parsuraman, A., Zeithaml, V.A. and Berry L. L. (1988) ‘SERVQUAL: A Multi-Item Scale for Measuring Consumer Perceptions of Service Quality’, Journal of Retailing 64(Spring): 21–40. Parsuraman, A., Berry, L.L., Zeithaml, V.A. (1991) ‘Refinement and Reassessment of the SERVQUAL Scale’, Journal of Retailing, 67(4): 420–50. McDougall, G. H. G. and Levesque, T. J. (1994) ‘A Revised View of Service Quality Dimensions: An Empirical Investigation’, Journal of Professional Services Marketing 11(1): 189–209. Babakus, E. and Boller, G. W. (1992) ‘An Empirical Assessment of the SERVQUAL Scale’, Journal of Business Research 24: 253–68. Carman, J. M. (1990) ‘Consumer Perceptions of Service Quality: An Assessment of the SERVQUAL Dimensions’, Journal of Retailing 66(Spring): 33–55. Babakus, E. and Mangold, W. G. (1989) ‘Adapting the SERVQUAL Scale to Health Care Environment: An Empirical Assessment’, in P. Bloom, B. Weitz, R. Winer, R. E. Spekman, H. H. Kassarjian, V. Mahajan, D. L. Scammon and M. Leay (eds) AMA Summer Educators’ Proceedings: Enhancing Knowledge Development in Marketing. Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association. Parsuraman, A., Berry, L. L., Zeithaml, V. A. (1993) ‘More on Improving Service Quality Measurement’, Journal of Retailing 69(1): 140–7. Bojanic, D. C. and Rosen, L. D. (1993) ‘Measuring Service Quality in Restaurants: An Application of the SERVQUAL Instrument’, Hospitality Research Journal 18: 3–14. Getty, G. M. and Thompson, K. N. (1994) ‘The Relationship between Quality, Satisfaction and Recommending Behaviour in Lodging Decisions’, Journal of Hospitality and Leisure Marketing 2(3): 3–21. Saleh, F. and Ryan, C. (1991) ‘Analysing Service Quality in the Hospitality Industry Using the SERVQUAL Model’, The Service Industries Journal 11(July): 324–43. Saleh, F. and Ryan, C. (1992) ‘Client Perceptions of Hotels – A Multi-Attribute Approach’, Tourism Management 3(92): 163–8. Downloaded from jvm.sagepub.com at Universiti Teknologi Malaysia on May 6, 2012 Ramsaran-Fowdar (25) Tsang, N. and Qu, H. (2000) ‘Service Quality in China’s Hotel Industry: A Perspective from Tourists and Hotel Managers’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 12(5): 316–26. (26) Saleh and Ryan, ref. 23 above. (27) Parsuraman et al., ref. 14 above. (28) Parsuraman et al., ref. 13 above. (29) Getty and Thompson, ref. 22 above. (30) Cronin, J. J. Jr and Taylor, S.A. (1992) ‘Measuring Service Quality: A Reexamination and Extension’, Journal of Marketing 56(3): 55–68. (31) Ministry of Tourism and Leisure, Mauritius (1997) ‘Vision 2020 Tourism’, pp. 7.1–7.23. (32) Nield, K. and Kozak, M. (1999) ‘Quality Certification in the Hospitality Industry: Analysing the Benefits of ISO 9000’, Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly 40(2): 40–5. (33) Ministry of Tourism and Leisure, Mauritius (1999) ‘Survey of Ongoing Tourists’, August. (34) Juwaheer, T. D. and Ross, D. L. (2003) ‘A Study of Hotel Guest Perceptions in Mauritius’, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 15(2): 105–15. (35) Parsuraman et al., ref. 13. Downloaded from jvm.sagepub.com at Universiti Teknologi Malaysia on May 6, 2012 Page 27