Minimum Drinking Age Laws: Effects On American Youth 1976-1987

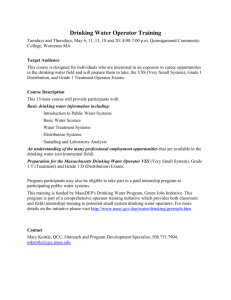

advertisement