The Meiji Restoration (1868-1912) was a revolutionary period in

advertisement

The Meiji Restoration (1868-1912) was a revolutionary

period in Japanese history. With the return of political

power to the emperor, Japan was thrust into the modern

world in an attempt to avoid Western dominance which

was already the fate of China, the Dutch East Indies and

the Indian subcontinent.

1868 marked the beginning of a deliberate

transformation by Japan and its new leaders in response to

the threat posed by the West. Western technology and

foreign expertise were imported; modern communications

such as the railway and telegraph were established;

strategic industries were developed for the purpose of

defence; and taxation was reformed to sponsor industry

and promote enterprise. By the turn of the twentieth

century, Japan had almost achieved a level of economic

growth eqnal to that of the Western powers.

Along with the success of the Restoration years, Japan

adopted excessive Westcmisation. Western ideas, fashion

and food dominated the early part of the period. The

status of Japanese women, however, did not improve.

Under the Meiji Constitution of 1889, they were not

accorded with political rights and continned to playa

snbordinate role to men.

The Meiji Restoration saw Japan's involvement in two

snccessfnl wars against China and Russia. With its

reputation growing on the world stage, Japan formed an

alliance with Britain in 1902 and annexed Korea in 1910.

In a period of less than fifty years, Japan was able to

retain its independence and find 'a place among the

aggressors instead of among the victims of aggression'.

responsible for creating the new goverument and initiated

many of Meiji's early reforms.

The Charter Oath

Emperor Meiji

and the Charter

Oath

In April 1868, Emperor Meiji made clear his government's

intention to modernise the country when he issued an

Imperial Oath of Five Articles (often known in English as

the Charter Oath). It became an important statement of

imperial policy regarding Japanese reform.

By this oath we set up as our aim the establishment

of the national weal on a broad basis and the

forming of a constitution and laws.

The

young emperor

When Mutsuhito became emperor of Japan in 1867,

he was only fifteen years old. In the following year,

he dismissed the ruling shogun and ended more than

two and a half centuries of Tokugawa rule. His uame

or title~ was soon changed to Meiji (meaning

'enlightened rule') and so began a remarkable period

of change which historians generally refer to as the

Meiji Restoration.

The Meiji Restoration marked the real beginning of

Japan's modernisation and entry into the international

world. It should not be assumed, however, that absolute

power was transferred to the emperor. After all, he was

still very young and in the early part of his reign Nijo

Nariyuki served as regent (seesho).

The driving force behind the economic, social and

political changes of the Meiji Restoration were the

Article 1

Deliberative assemblies shall be widely established

and all matters decided by public discussion.

Article 2

All classes, bigh and low, shall unite in vigorously

can-ying out the administration of affairs of state.

Article 3

The common people, no less than the civil and

military officials, shall each be allowed to pursue

his own calling so that there be no discontent.

Article 4

Evil customs of the past shall be broken off and

everything based upon the just laws of Nature.

Article 5

Knowledge shall be sought throughout the world

so as to strengthen the foundations of imperial rule.

The fifth article of the Charter Oath was perhaps the

most important for Japan as it promoted a new policy of

young samurai from the Satsuma, Chashu, Hizen and

Tosa clans who had helped defeat the shogun and

restore the emperor to power. They were largely

Ii.

~2 ')~l~

't

Figure 9.1 An illustration of brick and

stone shops on GinzaAvenue, Tokyo, during

the Mei;i Restoration

I

1I

early Meiji government for a number of years, although

the Constitution of 1868, having been hastily prepared,

proved unworkable and was later abandoned.

The end of feudalism

The new government's first task was to establish its

power over all the 260 feudal domains (han). Some of

them had become almost independent states ruled by their

daimyo during the final years of the Tokugawa

shogunate. Japan's leaders could not hope to create a

fully centralised governmeut if they were constantly

challenged by powerful lords exercising their feudnl

powers.

Figure 9.2 Emperor MeUi in a military uniform,

adomed with medals

modernisation along Western lines. Japan's new leaders

realised that unless their country modernised and became

strong militarily it would forever be at the mercy of

Western demands. The cry of sanna joi was replaced by

the ancient Chinese ideal of 'rich country; strong

military' (jukoku kyo/wi). One historian later made the

following observation.

Defence, therefore, became the main task of the new

government, while those numerous Japanese whose

fear of the Western nations was mingled with

admiration of their prowess overseas considered that

the adoption of Western material equipment might

enable Japan to find a place among the aggressors

instead of among the victims of aggression.

The Constitution of 1868

I

i

I

Japan's first constitution (Seitaisho} was drawn up in

June 1868 to bring the Charter Oath into effect and to

define the powers of the new government and the rights

of the Japanese people. Its main features were:

All authority was vested in a Council of State, or the

upper house of the Japanese parliament, known as the

D{{jokan

• Council members were not elected but chosen

according to noble rank

• The Deliberative Assembly, or lower house, held little

power and was called the Giseikan

Assembly members were elected from each clan, city

and prefecture of Japan. Only qualified men could

hold a seat in the Giseikon.

Ruling Japan in the emperor's name, members of the

Choshu, Satsuma, Hizen and Tosa clans dominated the

The new government was already in control of those

han whose military strength had brought about the Meiji

Restoration. Having persuaded their own daimyo to give

up their feudal rights, the new leaders set about

destroying the feudal powers of the rest of the daimyo. On

25 July 1869, Emperor Meiji issued an imperial decree

which forced all daimyo to surrender their lands (fiefs)

and the powers that went with them.

The court nobles [kuge] and the feudal lords

[shako] are given the same rank, and are to be

called kazoku. Those who have not yet given up

their fiefs are to be compelled to hand back their

registers. The feudal lords are created chiha'1ji

[governors of the han].

Two years later, the process was complete. On

29 August 1871, the fonnerterritories of the shogun were

divided into a new system of districts or prefectures

known as ken. With Tokyo the new imperial capital,

central government had become a political reality in

Meiji Japan.

ofApril 1868 (Document

follov.·inE

to be pointing

Rrnn,errlr Meiji and his

Building a

modern economy

1868-85

In 1868, Japan was anon-industrialised country, Three

quarters of the workforce was employed in agriculture

or farming and related handicrafts (such as cotton and

raw silk) produced nearly 65 per cent of the national

income, Most industries still used traditional methods

of production with very little emphasis on

manufacturing even in large scale enterprises let alone

factories. As the old financial and administrative

system associated with feudalism disappeared, the

great effort to catch up with the West began.

Shokusan [(oygo

Industria,lisation became a key aim of the Meiji

period. Between 1868 and 1881, the foundations of

modern industry were laid in Japan. Central to this

development was the government policy of

sponsoring industry and promoting enterprise known

as shokusan koygo. It became a major cornerstone of

the restoration program and gave Japan a new

economic outlook. This in turn encouraged economic

freedom at the expense of the old feudal restraints

that had prevailed in Tokugawa Japan.

The importance of strategic

industries

The Meiji leaders realised that if Japan was to

become a 'rich country:_ with a 'strong military' it

must develop strategic industries on which modern

military power depended:"'heavy industry,

engineering, mining and shipbuilding. This had

begun before the end of the shogunate.

Western military industries were first introduced

into Japan by some of the stronger clans for defence

purposes. Tbe Hizen clan built the first successful

reverberatory furnace in 1850 and began producing

iron guns in considerable number after 1852. The

shogunate soon followed suit. By 1865 it had two

modern shipyards in operation at Nagasaki and

Yokosuka.

With the fall of the shogun, the Meiji government

gave priority to developing defence 'industries which

could withstand the Western menace. Foreign instructors

were employed to give technical training to Japanese

workers in munitions plants and shipyards. Various

institutions were created for training in the manufacture

of guns. Engineering, technical and naval schools were

also founded using foreign instructors while the best

Japanese students were often sent abroad to master the

techniques required in these key industries.

Mining was developed on the same lines. The Meiji

government took over all of the mines formerly operated

by the Bakufu and employed the best foreign experts to

increase mineral production. By the end of the Meiji

period, Japan ranked as one of the world's largest

producers of coal and exporters of copper.

Early financial problems

With the defeat of the shogun, the Meiji government

faced a number of financial problems. The cost involved

in crushing the clans hostile to the imperial regime had

led to heavy public spending at a time when revenue was

very difficult to obtain. In 1868, national government

expenditure amounted to thirty million yen while the

rnoneygained from land taxes and other sources of

income was only three million. This imbalance had a

severe effect on the economy, Inflation ran high, internal

revenue dropped and the CUlTency lay in a state of chaos

as there was no one standard by which to trade. One

historian made the following comment.

The currency situation was indeed alarming; the

monetary circulation comprised not merely of new

issues of inconvertible notes, but also gold and

silver coins in .varying degrees of value-an

inheritance of the shogunate-and about 1500

varieties of clan notes.

In order to overcome the early financial problems of

the Meiji period, the yen was officially adopted as the

basic unit of currency in 1871. In that year, the government

suspended the exchange of clan notes or paper money

that had been issued by the daimyo ever since the late

sixteenth century. By 1879, the replacement of clan notes

had been completed.

Banking

The new land tax

At the end of the Tokugawa period, Japan had a higher

level of potential savings than most under-developed

countries in Asia today. However, it lacked a modern

bauking system to collect its untapped wealth and make

it available for investment on a large scale.

In 1872, the American system of national banking was

taken as tbe model for Japan and four national banks were

established under pressure from tbe government. By

1875, all were in serious financial trouble due largely to

poor management, lack of co-operation and failure to

compete with foreign banks and local institutions.

In 1882, a centralised, European-style system of banking

took the place of the earlier American system. In that year,

the Bank of Japan, the nation's first central bank, was

formed. It controlled the nation's banking system as a

whole and encouraged the development of specialised

banks to finance industry, agriculture and foreign trade. The

most important of these was the Yokohama Specie Bank

which wasfounded in 1880.

In 1873, the government needed to reform taxation in

order to ease the burden of heavy public spending on new

capital for industry. A land tax was introduced. Farmers

had to pay 3 per cent of their annual crop to the government.

The land tax became Japan's largest source of revenue

during the Meiji period and financed its transition to a

modern economy. But, although reduced to 2.5 per cent

of the annual crop in ] 876, it remained a heavy burden on

Japan's farmers.

Figure 10,1 Tokyo railway station in 1872

The land tax as a source of Japanese revenue,

1868-97

Years

1868-81

1890

1897

Land tax as a percentage of ordinary revenue

78%

50%

30%

Figure 10.2 Thefirst Japanese steam train, built in 1895

Modern communications

The Meiji Restoration brought ecouomic changes to

Japan quite quickly. The most visible were modern

communications such as the telegraph and railway. In

1872, the first railway line was laid between Tokyo and

Yokohama, and within a short time was carrying almost

2 million people a year. A similar liue was built from

Kobe to Osaka in 1874 and later extended to Kyoto in

1877. Telegraph lines, which were cheaper to construct

and operated at first only within Japan, linked all the

major Japanese cities by 1880.

The rise of the Zaibatsu

In the early years of the Restoration, the Meiji government

was the key player in Japan's industrial modernisation.

Using foreign instructors, it established the major mines,

factories and shipyards. But by the 1880s it needed a new

direction to ensure continued economic growth. On

5 November 1880, it published the Regulations on the

Transfer of Factories, abandoning the policy of

government control of industry.

The government began selling off certain industries to

private companies, often on very generous telIDS. These

favoured companies grew into large business combines

called Zaibatsu.

Some of the outstauding names among the Zaibat~u .

included Mitsui, '{asuda, Furukawa, Kawasaki,

Mitsubishi and Sumitomo. Although not all industries

were sold off to private interests, the Zaibatsu provided a

strong financial base for industry and promoted rapid

economic growth when it was most neede?

Activities

1 Refer to the illustration of Tokyo railway station

.in 1872 and answer the following questions.

a What type of scene is depicted?

b To What e)<.tent had Japan modernised by

1872?Give examples.

C Why (.10 you think this illustration was

produced?

2 Why do you think the creation of Japan's first

~team train in 1895 was a major achievement of

th~Meiji Restoration?

Japan1s cultural revolution

The world in thc late nineteenth century was dominated

by Western countries such as Britain, France, Germany

and the United States of America. Many in Japan felt that

in order to be accepted as equals it was necessary to adopt

not only Western science and technology, but all aspects

of Western culture.

During the first two decades of the Meiji Restoration,

a fascination for all things Western pervaded society.

'Civilisation and enlightenment' (bummei leailea) became

the popular catch-cry as Western liberlli thought was

introduccd into Japan in a very short space of time.

Many Japauese writers and intellectu~lsrejected their

traditional institutions and the learning that underlay them

for the path of 'universlli progress' that the West seemed

to represent. Fuknzawa Yukichi, perhaps the most

a

The Japanese living in towns and cities were keen to

adopt Western ideas and fashions. Food, clothing and

education changed in the attempt to imitate all

aspects of Western culture. But Westernisation

brought problems for the samurai.

.

Problems with the sarrru.rai

The changes of the Meiji period dramatically affected

the lives of the samurai~ as thegovernlIlel1tst~a<iilY

removed the privileges they enjoyed.

influential writer of the period, was critical of his

country's achievements when compared to the West. He

believed that Japau could only become strong if it had a

revolution in values and ideas.

If we compare the knowledge of;the Japanese and

the Westerners ... there is not one thing in which

we excel ... Who could compare our carts with

their locomotives, our swords with their pistols? ...

We think that our country is the most sacred, divine

1869

The old feudal hierarchy wasr~pl~ce~

with new social classes. Court officials

and daimyo became nobles (kdzdkLt).

Samurai were classed as landowners

(shizoku) or soldiers (sotsuzoku), and all

the remaining classes, inc1udingollfeasts,

were gronped together as commoners

1871

The government made the wearing of

swords optional and allowed men t6 cut

off their topknots. Many samurai refused

to do this.

Conscription was ir,trodw,ed

year-old cOllSCriplts

army for three

was clear

being taken over bYG~~;;;ri;~ed ";."""C.~

In March, the Hatori Ediictjprohibited

wearing of swords

ceremonial occasions.

Saigo Takamori, the ll1.UUm,y

Satsuma forces

overthrow the 8"i)!?','"

30 000 ex-"amurai

government

bitter fighting,

defeat, and his wuuwc» pelislled

hands of the

®l)§rilli

anIly. This became kJ"ovvn

Rebellion.

(heime11).

1872

1876

1877

land; they travel about the world, opening lands and

establishiug couutries ... All that Japau has to be

prond of ... is its scenery.

Fashion and food

Under the Tokugawas, the dress of the social classes was

strictly ruled. While the upper classes could wear sillcs

Figure 11,1 The enlightened, half-enlightened and unenlightened

Japanese man

Figure 11.2 A scene in a Japanese classroom

after the turn of the century

and satins, peasants were limited to hemp and cotton.

This changed in 1872. The Meiji government decided

that Western dress should be woru for all court aud

official ceremonies. Later, the cutaway or 'morning coat'

(moningu) became the standard dress for formal

occasions. Westem-style haircuts became a major symbol

of Westeruisation in Japan and as early as 1870 had

largely replaced the traditional samurai topknot. Meat

eating was encouraged at the expense of traditional

Buddhist beliefs wbich considered it immoral. The beef

dishes, Sukiyaki and Teriyaki, proved most popular.

Bread, beer and dairy products also appeared.

Ballroom dancing emerged as a particularly popular

pastime in the early Meiji period. An elaborate, twostorey social halI in Tokyo, calIed the Rokumeiken

opened in 1883 to hold dances every Sunday night for

wealthy husiness people, politicians and foreign

diplomats. Its closure in 1889 marked the end of the

Japanese craze for Westernisation, as many came to

favour a 'return to being Japanese'.

Changes in education

The Meiji government believed that a modetnised society

needed an organised system of education. Under the

Tokugawas, ordinary people were taught reading, writing

and the abacus (a device of beads strung ou rods used for

calculating) in terakoya-smalI makeshift classrooms in

people's houses. In 1868 there were nearly 13 000

terakoya in Japan with a total of 837 000 students.

Education under Emperor Meiji owed much of its

rapid progress to the traditional terakoya system. In 1871,

a Ministry of Education Was established to provide

education to alI people, regardless of their social class or

gender. In 1872, it was decreed that all Japanese children

must have at least four years of primary schooling. By

1910, 98 per cent of Japanese students were receiving

compulsory education.

As schools spread across the country, Japan's first

tertiary institution, Tokyo University, was founded in

1877. Nine years later, it was reorganised into a genuine

multi-faculty university and became the principal training

centre for future government leaders. Other universities

were later established in Kyoto (1897), Fukuoka (l9lO)

and Sapporo (1918).

The Rescript on Education

In 1890, Emperor Meiji introduced his famous, 'Rescript

on Education', which stressed the importance of harmony

and loyalty to the throne. It was given great reverence

throughout the land and a copy was display~d in every

school and read aloud on special days. The 'Rescript on

Education' formed the basis of Japan's philosophy on

education until 1945. Part of it read as folIows.

, Ye, our subjects, be filial to your parents,

affectionate to your brothers and sisters; as

husbands and wives be harmonious, as friends true

... pursue leaming and cultivate arts, and thereby

develop your intellectual faculties and perfect your

moral powers ... always respect the Constitution

and observe the laws ... and thus guard and

maintain the prosperity of Our Imperial throne.

Activities

1 'Y!'ydid Fu1cazawa Yukichi helieve that Japan

needed a revolution in values and ideas

(Document A)?

2 Study Figure 11.1 and explain how the artist saw

the major differences hetween the enlightened,

half-enlightened and unenlightened Japanese

manofthe Mdji Restoration?

3 What do you uotice about the photograph of a

Jap,mese classroom in the early twentieth century

(Figure I I.2)? What evidence is there to suggest

(hallapan's system of compulsory education had

been a success?

Consisting mainly of ex-samurai and commoners

(heimin), The Freedom and People's Rights Movement

demanded a popular assembly or government so that

decisions would retlect the will of the people and thus

preserve national unity. Itagaki later reorganised this

movement into a major political party which took the new

name of Liberal Party (Ii)'uta).

Ito Hirobumi and

the Constitution

of 1889

Towards the end of the nineteenth century, it was

widely believed that constitutions (systems of

fundamental laws and principles of a government)

provided the unity that gave Western powers their

strength. The Japanese leaders were keen to set up a

system of constitutional governrnent

Problems with the

Constitution of 1868

Under Japan's first constitution kno\Vn;asth"

Seitaisho or the 'Constitution of 1868' the Dajdkan,

a Grand Council of State consisting ofseyen

departments, held all political power. Althoughtlie

Dajokan was effective in the early years of rapid

economic and social change, it was opposed by

different groups because it failed to deal with two

basic problems: it did not provide Japan with a

modern constitution and a national parliament· that

would earn Western respect and popular support.

The Freedom and People's

Rights Movement

During the Restoration, a small group of men known

as oligarchs, ruled Japan in the name of Emperor

Meiji. These men tolerated little opposition until a

number of them left the government over the

question of invading Korea (Seikanron) in 1873. This

division promoted an important.de~()SFaJis

movement which was led by Itagaki Taisuke and

called The Freedom and People's Rights Movement

(Ii)'u Minken Undo).

Towards a new constitution

By 1875, the oligarchs recognised the problems with

Japan's first constitution in the Osaka Agreement. It

called for the creation of a constitutional government in

gradual stages and a new body of officials called the

Senate (Genroin) was appointed by the emperor to draft

a second constitution.

Between 1876 and 1878, the Senate prepared four

draft constitutions which were too liberal for the powerful

oligarchs such as 1wakura Tomomi and Okubo

Toshimichi. As a result, Iwakura asked the chief

members of the oligarchy to submit their own views on

constitutional government in 1879. All complied with

fairly cautious statements, except Okuma Shigenobu,

who astounded his colleagues with the radical nature of

his proposal. He suggested that elections be called

immediately and that Japan adopt the full parliamentary

system of Britain. As a result, Okuma was forced out of

the government, although the constitution movement

continued.

ln 1881, Emperor Meiji promised the Japanese people

that a new parliament would be convened in 1890.

We therefore hereby declare that We shall in the

23rd y£ar oLMeiji,. establish a Parliament in order

to carry into full effect the determination We have

announced, and We charge' Ourfaithful subjects

bearing Our commissions to make, in mean time,

all necessary preparations to that end.

Ito Hiroburni, an ex-samurai who had worked to

restore the emperor to power and who was a member of

the new government, was the architect of Japan's second

constitution, The Constitution of the Empire of Japan

(Dai Nilum Teikoku Kempa).'

Ito and the Prussian model

The son of a peasant farmer, Ito was born in Choshll

province in 1841. His long political career spanned nearly

the entire Meiji period from his involvement in the

struggle to overthrow the Tokugawa shogunate to his

assassination by a Korean nationalist in Manchuria in

1909. Apart from becoming prime minister on four

occasions, Ito's greatest achievement remains the

creation of the Constitution of the Empire of Japan

,

between 1881 and 1889.

When Okuma left the government in 1881, Ito moved

into a position of unchallenged power, having favoured a

gradualist approach in drawing up a second constitution.

Determined to base it on the best possible practices of the

West, adapted to Japan's special needs, Ito and his

colleagues travelled to Europe on a study mission in

1882. On their return in August 1883, Ito decided that a

constitutional system that operated under alLabs61ute

monarch or emperor was best suited to Japan. The model

he adopted was based on the Prussian (German)

parliamentary system.

Meanwhile, Okuma and his followers, who opposed

all constitutional models except the BI'itish, founded a

political party called the Progressive Party (Rikken

Kaishinto) in an attempt to influence political decisions.

Divided into factions, the Progressive Party soon fell

apart and Okuma had little choice b)"t to return to the

government. In February 1888, he was appointed Foreign

Minister of Japan.

~-

Figure 12.1 The opening afthefirst session afthe Japanese Die! in

the presence ofEmperor Mei;t, 1890

The Meiji Constitution

Under Ito's direction, a German, Hermann Roesler,

helped to complete the new constitution. On 11 February

1889, Emperor Meiji handed down, as a gift, the written

constitution to Prime Minister Count Kuroda. The main

points of the constitution were;

• The emperor was the absolute ruler or head of state. He

was sacred and inviolable and had complete control of

the armed forces and the nation's foreign policy.

The emperor could dissolve the parliament (known as

tbe Diet), create his own legislation, or veto (dismiss)

any legislation which carne from the Diet itself.

• Individual ministers who belonged to the cabinet (the

decision making body of the ruling government) were

responsible to the emperor, and not to the Diet.

The Diet was comprised of two Houses (a bicameral

system):

- the House of Peers was the upper house of

• The House of Representatives was not a truly

representative body for two reasons:

- Japanese women could neither vote nor become

political representatives of the Diet at this time.

- About only 1 per cent of the population had the

right to vote due to tax qualifications.

Although it appeared that the emperor had far

reaching powers under the new constitution, he remained

essentially a symbol or figurehead of the nation. The

powelful group of oligarchs (genm) often acted in his

name. Ito was among these and it is not surprising that

there was no mention of their powers in the Constitution

of 1889.

parliament and acted as a 'House of Review'. Its

members were largely former daimyo who were

given life appointments.

- The House ofRepresentatives was the lower house

of parliament which consisted of a group of 300

men who were elected every four years.

the

he

sylnhol or figurehead of

In 1876, Japau forced the openi~gbfK6fea; using the

same gunboat diplomacy (bullying tactics) that Perry had

nsed against itself in 1853, The resulting Treaty of

Kanghwa opened three Koreau ports for trade, but more

importantly Japau recognised Korea as au independent

state in order to detacb it from China's control,

Sino-Japanese

Wa'r

1

Yamagata Aritomo

The Japanese army, under the leadership of Yamagata

Aritomo, had decided that for its own security Japan

needed some measure of control over Korea, even if it

meaut war with China, In 1883 Yamagata saw conflict

over Korea as inevitable and stated: ',,, the high-handed

attitude of the Chinese toward Korea, which was

antagonistic to the interests of Japan, showed OUT officers

that a great war was to be expected sooner or later on the

continent, and made them eager to acqnire knowledge,

for they were as yet quite unfitted for a continental war.'

Prelude to war

In 1894, a rebellion against the corrupt government of the

King of Korea by a popular religious group, the Tong Hak

Society, broke out in southern Korea. The Tong Hak

Society wished to preserve 'EasternLearning' aud to rid

the country of all foreign influence, iucluding Japanese.

At the king's request, Chiua aud Japan sent troops to

help quash the rebellion. Japan's forces outnumbered the

small body of Chinese troops. By the time they arrived in

Korea, the rebellion had already been put down by loyal

Korean forces.

government to inten/erle

were eagel' for a mi'litary ~,dlli!"U/',U, eSIJecially

Korea's refusal

Meiji government.

Both countries refused to withdraw their troops. This

led to a stalemate, until Ito Hirobumi, the Japaues~ prime

minister, demanded sweeping changes to the Korean

government, which China refused. On 23 July 1894,

Japanese troops seized the king's palace and ordered him

to declare Korea's independence from Chiua.

As a captive of the Japanese, the King of Korea signed

an order expelling the Chinese. Two days later a Chinese

troopship, the Kowshing, was sunk by the Imperial

Japanese Navy after it had attempted to bring reinforceme.TIts into Korea. A state of war now existed

between China aud Japan.

The Sino-Japanese War

The war with China lasted less than a year and, on both

land and sea, the Japanese won decisive victories. News

of this success caught the world by surprise aud showed

the Western powers the extent to which Japan had

quickly mastered the art of modem warfare. One British

lieutenant made the following evaluation.

"

,

'%

fll!2lYJ(Pili//lflfk@1j11J. ~

- 0f ,,"

~~ -

"

I came to Japan expecting to see some miserable

parody of a third-rate European soldier; instead, I

find an army in every sense of the word admirably

organised, splendidly equipped, thoroughly drilled,

aud the strangest thing of all in an Oriental people,

cheaply and honestly administered ...

Timeline: Sino-Japanese War, 1894-95

1894

Events

1 August

16 September

17 September

21 November

Declaration of war

Quick Japanese victories at P'yongyang

Chinese warships defeated Yalu River

Port Artbur, Manchuria falls to the

Japanese

1895

Events

12 February

Final collapse of Chinese fleet at

Weihaiwei

Treaty of Shimonoseki ends war

17 April

The Japanese soldiers' loss of control at Port Arthur

threatened Japan's international reputation, especially

with nations such as Britain. As a result of their arWY's

actions, Japanese diplomats were forced on the defensive

as news of the atrocities was publicised worldwide.

The Treaty ofShimonoseki

On 17 April 1895, China and Japan signed the Treaty of

Shimonoseki, officially ending the war. The main

provisions of the treaty were:

China had to recognise Korea as an independent state

• the Liaotung Peninsula, Formosa (Taiwan) and the

Pescadores Islands were given to Japan

• 4 new Chinese ports opened to Japanese trades

Japan gained most-favoured nation rights on China, a

privilege long desired

China had to pay an indemnity of 200 million taels.

The Massacre at Port Arthur

The Manchurian fortress of Port Arthur was considered

oue of the strongest in Asia. Before the war, a French

Admiral declared it would take a mighty force from both

land and sea to break into it. His estimate was not far

wrong.

The Japanese siege of Port Arthur was a bloody,

drawn out affair lasting nearly three months. When the

fortress finally fell on 21 November 1894, total Japanese

losses surprisingly amounted to no more than 300. The

same could not be said for the Chinese. According to the

rep~)ft of James Creelman, a Western war correspondent,

Japanese soldiers, over several days, had massacred up to

60000 Chinese. The full extent of the massacre was later

revealed in the diary accounts of a number of Japanese

soldiers. Okabe Malao, a trooper in the Ist Division of the

Japanese army, recalled the following.

As we entered the town of Port Arthur, we saw the

head of a Japanese soldier displayed on a wooden

stake. This filled us with rage and a desire to clUsh

any Chinese soldier. Anyone we saw in the town

was killed. The streets were filled with corpses, so

many they blocked our way. We killed people in

their homes ... We shot some, hacked others ...

Firing and slashing, it was unbounded joy. At this

time, our artillery troops were at the rear, giving

three cheers [banzai] for the emperor.

Figure 13.2 'lap the Giant Killer'; a British cartoonist's view of

Japan's victory in 1895

infamous Triple Intervention, Russia forced China to

Russo-Japanese

War

1904--1905

grant it a twenty-five year lease on the Liaotung

Peninsula. In doing so, it was also given the right to

connect the Chinese Eastern Railway, which ran across

Manchuria to the Russian port of Vladivostok, with an

extension line south to the major ports of Darren and Port

Arthur. This new development, known as the South

Manchmian Railway, greatly alarmed Japan.

By 1900, Russia had gained considerable control over

Mancl;mria through its railway concessions. However, the

Russians soon felt their position in the Far East threatened

by events in China.

Problems in China

Ever since its humiliating defeat at the hands ofJapan in

1895, China's political and economic sitnation had

deteriorated and anti-foreign feeling had grown. In 1898,

a few enlightened Chinese leaders had persuaded their

The Triple Intervention

Japan's tliumph in the Sino-Japanese War was soon

soured by the way the major European powers

reacted to its success. In a Triple Interventi()n ",hich

shocked the Meiji government;RJIssiael1li~te~t~e

diplomatic support of France andGerlIlatlyt()f()rce

Japan to give up its claim on the Liaotung 1'9~il1s~Ia..

This action took place on 23 April 1895'.9111ysix

days after China's signing of the Treaty of

Shimonoseld.

Having little choice but to comply to the

collective force of three major European powers,

Japan gave JIp the Liaotung PeninsJIla in exchange

for an additional sum of thirty million taels. One

historian later described the impact of the Triple

Intervention on Japan.

new emperor to adopt far-reaching reforms to prepare

China to modernise and meet the challenge of the West.

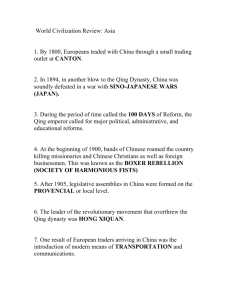

The so-called Hundred Days Reform was crushed by the

Empres·s Dowager, Tzu Hsi, who seized power and ruled

in the name of the emperor.

The Boxer Rebellion

The Empress Dowager decided to adopt a strong policy

against foreign powers in China. She decreed that China

would resist with force any future, unacceptable demands

made by the West. Her actions gave rise to a widespread

anti-Christian, anti-foreign revolutionary movement in

the north of China known as the Boxers or Society of

Righteous and Harmonious Fists. The name was probably

derived from their practice of body streugthening

vx.~1;J;i~_~s whichresembl~dboxing.

For more than two months in 1900, the Boxers lay

siege to the Chinese capital, Peking. During the rebellion,

regular Chinese forces were ordered to attack Manchuria.

In reply, Russia sent troops stationed in Siberia to crush

the Chinese. By October, they had been successful;

Japan's emotions had gone full cycle: from

cool determination before tak~ng on the

Chinese in war; through euphoria O\~er victories

Manchuria, an established province of China, was now in

in all aspects of the war; to a sense of

Westerners in China and on Chinese converts to

humiliation that she could not withstand the

pressure of the three world bullies. This led to

a popular mood of determination to lie low and

malce sure by preparedness that this weakness

would not be manifested again.

Christianity, was finally crushed by an international army

that included a Japanese force.

Russian designs on

Manchuria

Russia's designs on Manchmia would

by the Japanese. In 1898, three years

Russian hands.

The Boxer Rebellion, which was really an attack on

Anglo-Japanese Alliance

Russia's advance iu the Far East worried both Britain and

Japan. Less than a year after Boxer rebels had laid siege

to Peking, Britain and Japan decided to renew

negotiatious towards a formal alliance. Femful of Russian

moves in the East and its own diplomatic isolation in the

West, Britain saw the benefits of a defensive alliance with

Japan. Not all Japanese leaders favoured such an alliance.

Many believed an alliance with Rnssia wonld best protect

Japan's interests in Korea. Aware of such views in Japan,

Francis Bertie, Asian Chief of the British Foreign Office,

made the following observation.

Unless we attach Japan to ns by something more

substantial than general expressions of goodwill, we

shall run the risk of her making some arrangements

which might be injnrious to our interests.

Britain sncceeded. On 30 Jannary 1902, the AngloJapanese Alliance was signed. Its main features were:

both countries agreed to recognise the special interests

of Britain in China and of Japan in Korea

each nation could take necessary measures to protect

its special interests if they were threatened by the

aggressive action of another power, or by disturbances

within China or Korea

• both countries promised to remain neutral if either

became involved in a war to protect those interests

• hoth agreed to aid the other if a third power entered

into ky such 'wulon the enemy side

• the agreement was to remain in force for five years.

Russia and Japan

With Blitain, the strongest power in the Far East, as an

.ally, Japan was inarnuch stronger position to oppose

Rnssian expansion. Most of all the Japanese leaders

wanted to get Russia to recognise and respe~t its special

position in Korea. One Japanese official provided the

following explanation in 1871.

At an Imperial Conference in 1903, Japan offered to

recognise Russia's rights in Manchuria if Russia would

recognise its interests in Korea.

Despite lengthy negotiations, Russia wonld

only partially agree to Japan's reqnest. It would not

agree to Japan's proposal to use Korea for 'strategic

purposes' as it might threaten Russia's exclusive line of

communication, its railway from Darren and Port Arthur

to Vladivostok. When Rnssia refnsed to bndge on the

qnestion of Korea, the choice left open to Japan was clear.

The Russo-Japanese War

Japan decided to win control of Korea at all costs.

Withont warning, on 8 Febrnary 1904, Japanese naval

forces torpedoed the Russian naval fleet anchored at Port

Arthur, causing severe damage. Two days later, war was

declared.

Within three months, Russian troops had been driven

out of Korea. Although snffering heavy losses, the

Japanese alwy pushed north into Manchuda, crossing the

Yalu River and capturing Port Arthur (after a five month

siege) and then the city of Mukden. At sea, the Japanese

navy under Admiral Togo routed the Rnssian fleet in the

Straits of Tsushima (it had just arrived after spending

seven months sailing ronnd the world from the Baltic Sea

in Europe).

Territory gained

in Japanese victories

against Russian

troops

CHINA

In naval warfare, Japan is easy for the enemy to

attack but hard for ns to defend. Therefore, if we

waut to preserve [our] independence permanently,

we must possess territory on the continent. There are

only two countries ... Japan can seize, China and

Korea. Stndents with little expelience iu the world

eugage in foolish talk about how harharic and

nnprincipled this would be ... To strengthen Japan

by war is to show loyalty to our country and to our

sovereign. That should he our gniding principle.

Figure 14.1 The areas offighting during Ihe Russo-Japanese

War. 1904-1905

-I

i

Figure 14.2 The movement ofRussian troops during the

Russo-Japanese War, 1904-1905

Timeline: Russo-Japanese War, 1904-1905

1904

Events

10 February

May

Japan declares war on Russia

Japan's victory in a bloody battle on the

Yaln River gave it control of all of

Korea

Japanese troops moved into the south of

Manchnria

September

1905

Events

2 Jannary

General Nogi, the Japanese Army

Commander, captnred Port Arthnr after

a five-month siege

After a two month land battle, the city

of Mukden fell to the Japanese

The Russian fleet was destroyed by the

Japanese in the battIe of Tsushima.

The Treaty of Portsmouth ended the

war.

March

27-28 May

5 September

The Treaty ofPortsmouth

The Anglo-Japanese alliance was an important milestone

for Japan, but its defeat of Russia was uuprecedented. It

was the first time any Asian power had beaten an

established European nation. Although this was a

remarkable victory, the Japanese forces had incurred

serious casualties. As a result both Russia and Japan

accepted the offer made by Theodore Roosevelt,

President of the United States of America, to act as

peacemaker. The signing of the Treaty of Portsmouth (at

New Hampshire in the United States of America), on

5 September 1905, finally brought the war to an end. Its

main provisions were:

Russia recognised Japan's interests in Korea

the lease of the Liaotung Peninsula was transferred to

Japan

Russia surrendered its coutrol of the South

Manchurian Railway to the Japanese

Japan acquired the southern half of the island of

Sakhalin

both nations agreed not to interfere with any decision

China might malce in the fntnre to develop Manchuria.

Figure 14.3 'Chincl'appears slightly in the way.'

An American cartoonist's view of the

Russo-Japanese War

Activities

1 Using Docnment A, explain the emotional impact

of the Triple Intervention on Japan, What popular

mood emerged from this crisis?

2 Refer to the map of the Russo-Japauese War,

1904-1905 and answer the following questions:

a Why might railways have become au

importaut target during the conflict?

b Suggest reasons why China may have feared a

Japanese victory?

3 Examiue Figure 14,3.

a Provide a brief historical backgrouud of the

events shown in the cartoon.

b Describe the main elements of the cartoon,

including the metaphors and symbols.

c Describe the overall message that the

cartoonist is attempting to convey.

d What is the main purpose of the cartoon? Is it

biased, accurate or effective?

This attitude did little to provide a clear impression of

Japanese progress during the Meiji Restoration. In 1881

a leading English newspaper in Japan commented on this

idea of progress.

Effects of the

Meiji Restoration

Meiji imperialism

The Meiji Restoration marked a major turning point

in Japanese history. Japan expanded from a closed

feudal state into an empire reaching into East Asia.

By 1910, Japan had acquired Formosa (Taiwan) as a

colony, obtained extensive· economiccpntrol in

southern Manchuria, won the southern half of the

island of Sakhaliu and annexed Korea. This rapid

expansion provided the security for Japaritti pteseIye

its independence aud meet the challenge oftheWest..

By the time of Emperor Meiji'sdeath 1

Japan had strengthened itself through war and

11 1,,12,

industry, becoming a modern nation and an

imperialist power.

-Differing views

Not everyone was enthused by the neW possibilities.

The yatoi, foreign experts, who came to supervise

factories and mines and train Japanese techniciaris,

often complained ahout their existence, mainly

because they could not or would not try to understand

the ways of the Japanese, so different from their own.

One histo~ian commented on these attitudes~

Under the unequal treaties and extraterritoriality, wherebyeach foreign subject was

governed by his own consulate and was outside

the laws of Japan, they tried to exploit their

privileges aud regarded their Japanese hosts as

merely an awkward set of people with customs

that did not conform to their own ideas of

'civilisation', but had to be tolerated because

they were a means to riches for themselves.

Jap,m for many of them was like a gold-mine.

They had to go down into the darkness, remain

there for a period, and having grabbed their

nuggets, escape back from whence they came.

Wealthy we do not think [Japan] will ever become:

the advantages conferred by nature, with the

exception of climate, and the love of indolence and

pleasure of the people themselves, forbid it. The

Japanese are a happy race, and being content with

little, are not likely to achieve much.

At the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War, a more

realistic appraisal of Japan was voiced. Noting the failure

of the West to take Japan seriously, the London Times

wrote the following on 11 February 1904.

The story of the last ten days must have fallen upon

the western world with the rapidity of a tropical

thunderstorm ... That is the trouhle at the root of

the present situation-the past inability of the West

to take Japan seriously ... All this is due to the

superficial study of Japan which has characterised

Western contact with it. We as a nation alone

appear to have formed a shrewder estimate ... But

for the rest, they ... thought of the nation as a

people of pretty dolls dressed in flowered silks and

dwelling in paper houses of the capacity of

matchboxes.

In less than fifty years, Japan had changed from a

feudal society to become a world power that could hold

a major industrial exhibition in London and defeat an

estabiished European power in a full-scale modern war.

This was a unique achievement.

The plight ofJapanese

women

Improving the status of women was not one the reforms

of the Meiji Restoration. Social customs, economic

realities and political and legal systems combined to

prevent women from asserting themselves, compelling

them to playa subordinate role to men. Fukuzawa

Yukichi, an advocate of liberal reform, wrote about the

status of women.

I

l

At home she has no personll1property, outside the

house she has no status. The house she lives in

belongs to male members of the household, and the

children sne rears belong to her husbaud. She has

no property, no rights, and no children. It is as if

she is a parasite in a male household.

In 1889, mauy women hoped that they would be given

political rights under the new constitution (Dai Nihon

Teikoku Kempa). This was not to be. In fact the political

situation for women grew more restrictive as the

following chart shows.

1882

1889

1898

The Meiji government forbade women from

making political speeches.

Women were banned from participating in

any political activities, even listening to

political speeches.

The Civil Code gave the head of the

extended Japanese family absolute authority.

He now had the right to control family

property, fix the place of residence of every

member of the household and approve or

disapprove offarnily marriages and divorces.

Wives could not undertake legal action aud

under one provision were considered to have

the same rights as cripples and disabled

At the turn of the twentieth century, Singapore

replaced Hong Kong as the centre of brothel prostitution

in South East Asia. Japanese prostitutes, brought to

Singapore to sustain its sexual economy, soon re31ised

that pride or family shame would preveut them ever

returning home. Thousauds of Japauese girls, bought or

abducted from their parents by procurers (zeegen), found

themselves trapped into working in foreign brothels by

the threat of violence and the obligation of debts. In his

study of prostitution in Singapore between 1870 aud 1940

James Warren described the tragic existence of the

karayuki-san (overseas prostitutes).

Procurers either used force or deception to lure

young ... girls away who, once in tbeir hauds, were

held there by money and the brothel owner's power

over them. Transported, tbey found themselves at

the end of a journey to au allegedly easier way of

life in the grip of the brothel-keeper, indebted and

with no prospect of regaining their liberty except

by repaying the sum advanced to their parents in

contract. Invariably they were powerless to protest,

with neither knowledge of the local language,

money nor clothes, and faced with constant

intimidation and encouragement from everybody

. ,. to become ~n inmate.

persons.

The flesh trade

Brothels were sanctioned by the Meiji government.

Impoverished peasant families, mainly in Kyushu, were

often forced to sell their daughters into a life of

prostitution either in Japan, bnt more often abroad.

For many women, the Restoration years· were a

disappointment. Their status in society saw little change

despite their contributions to the success and speed of

Japan's industrial revolution. The traditional ideal of

women as 'good wives and wise mothers' (ryosai kembo)

was so ingrained that mauy were simply forced to submit

and endure.

Activities

Figure 15.1 Two karayuki-san posing for the camera in

Singapore after the tum of the centwT

1 What do Documents A and B reveal

about Western attitudes to Japan

during the first two decades of the

Meiji Restoration?

2 What effect did Japau's victory in the

Russo~Japanese War of 1904-1905

have on Western opinion? Refer to

Document C.

3 What restrictions were placed

on women during the Meiji

Restoration? How did this affect

their status in Japanese society?