islamic art as a means of cultural exchange

advertisement

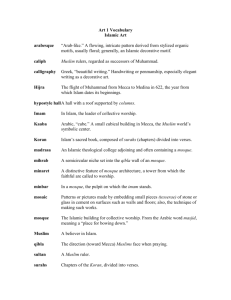

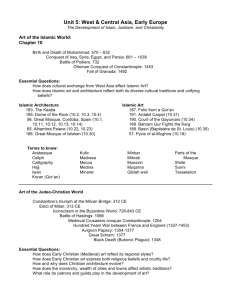

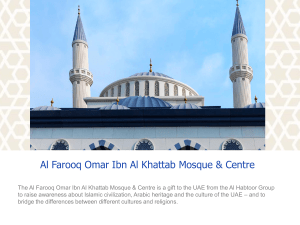

ISLAMIC ART AS A MEANS OF CULTURAL EXCHANGE Author: Chief Editor: Production: Release Date: Publication ID: H.R.H. Princess Wijdan Ali Prof. Mohamed El-Gomati Savas Konur November 2006 619 Copyright: © FSTC Limited, 2006 IMPORTANT NOTICE: All rights, including copyright, in the content of this document are owned or controlled for these purposes by FSTC Limited. In accessing these web pages, you agree that you may only download the content for your own personal non-commercial use. You are not permitted to copy, broadcast, download, store (in any medium), transmit, show or play in public, adapt or change in any way the content of this document for any other purpose whatsoever without the prior written permission of FSTC Limited. Material may not be copied, reproduced, republished, downloaded, posted, broadcast or transmitted in any way except for your own personal non-commercial home use. Any other use requires the prior written permission of FSTC Limited. You agree not to adapt, alter or create a derivative work from any of the material contained in this document or use it for any other purpose other than for your personal non-commercial use. FSTC Limited has taken all reasonable care to ensure that pages published in this document and on the MuslimHeritage.com Web Site were accurate at the time of publication or last modification. Web sites are by nature experimental or constantly changing. Hence information published may be for test purposes only, may be out of date, or may be the personal opinion of the author. Readers should always verify information with the appropriate references before relying on it. The views of the authors of this document do not necessarily reflect the views of FSTC Limited. FSTC Limited takes no responsibility for the consequences of error or for any loss or damage suffered by readers of any of the information published on any pages in this document, and such information does not form any basis of a contract with readers or users of it. FSTC Limited 27 Turner Street, Manchester, M4 1DY, United Kingdom Web: http://www.fstc.co.uk Email: info@fstc.co.uk Islamic Art as a Means of Cultural Exchange November 2006 ISLAMIC ART AS A MEANS OF CULTURAL EXCHANGE * H.R.H. Princess Wijdan Ali** Islamic art began as a catalyst for trends and styles borrowed from local Byzantine, Hellenistic, Coptic, and Sasanian artistic traditions. Yet, not long after, Muslim artists succeeded in developing most of the traits they had borrowed and created their own styles, motifs and fashion which conformed to the teachings of their own religion, thus shaping their own aesthetics. With the expansion of Islam over a vast area of land, the Arabs came into contact with different civilizations including Greco-Roman, Christian, Buddhist and Chinese. They also encountered indigenous artistic traditions that belonged to various cultures and societies such as those of the Berbers, African peoples, Slavs, Turks, Goths, among others. From these diverse local practices the Muslims chose what suited their beliefs and taste. This selective process, respected regional variety integrating and uniting this variety within the larger framework of Islamic civilization which stems basically from Islam as a faith and a way of life. After Islamic art matured and created its own styles, the inter-cultural exchange continued without having a deleterious effect on Islamic aesthetics. Figure 1. Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem The dissimilar cultural encounters, which were synthesized inside the Muslim consciousness, left their mark on Islamic art and created its most distinguishing trait: "unity within diversity" or "diversity within unity". Following are three examples that demonstrate the extent of borrowed influences Muslims adopted in their religious monuments without apology or remorse. Since antiquity, Jerusalem had been an important religious centre for both Jews and Christians, housing monuments such as the Church of the Holy Sepulcher and other churches and temples. When the Muslims took Jerusalem they needed a place where they could congregate for worship and wanted to build a monument that would testify to the glory of the new faith and witness the start of a new era. The Umayyad This article was first published in the Cultural Contacts in Building a Universal Civilisation: Islamic Contributions. Edited by Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu. Istanbul: IRCICA, 2005. This book can be obtained from IRCICA publication on their official website: www.ircica.org. We are grateful to Dr. Halit Eren, General Director of IRCICA for allowing publication. ** H.R.H. Princess Wijdan Ali is art historian, academic, painter, and art curator. * Publication ID: 619 COPYRIGHT © FSTC Limited 2006 Page 2 of 16 Islamic Art as a Means of Cultural Exchange November 2006 Caliph, `Abd al-Malik Ibn Marwan (685-705), selected a site that had a religious significance for his coreligionists. It was the Holy Rock from which the Prophet Muhammad, accompanied by the Archangel Gabrielle, journeyed to Heaven on a stairway of light to be instructed by God, and returned before dawn to Mecca. On this rock, that had absolutely no. trace of any ruins to attest to former habitation, `Abd al-Malik built the first religious monument in Islam (685-691). The Dome of the Rock (Figure 1), built by Byzantine and Arab architects and workers who benefited from the Byzantine style and interpreted it within the philosophical framework of the new faith mixing Greek traditions with Arab taste, became the third holiest shrine in Islam after Mecca and Madina. 1 Figure 2. Plan of the Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem The octagonal plan of the Dome of the Rock (Figure 2) taken from Byzantine church plans is similar to that of the Church of the Ascention on the Mount of Olives (Figure 3) and San Vitale in Ravenna whose circle circumscribing the building has the same diameter as the Dome of the Rock. However, the Muslim monument has a dome that is more important as a sign to be noticed from a distance than as a visible focus of an interior architectural composition. And alone among them it has no focus toward which one is directed. Only around which one may proceed. The whole geometry of the building's construction creates a visually magnetic shell for something sacred but avoids clarifying the liturgical usage and in this respect, it disconnects itself from the whole liturgical tradition of Christian churches and baptisteries. 2 Following the local trends in Syria, Jordan and Palestine, the columns, internal and exterior surfaces of the dome and the drum were all covered in green, blue and gold mosaics, mother of pearl and small coloured marble squares. The piers and beams were covered with brass sheets and beaten bronze in the form of a band of grape bunches and vine leaves, which make up one of the early patterns of Islamic decoration, inspired by Christian decorative forms (Figure 4). 1 2 W. Ali, the Arab Contribution to Islamic Art (Cairo, 1999), 107-9. O. Grabar, the Shape of the Holy. Early Islamic Jerusalem (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1996), 107-110. Publication ID: 619 COPYRIGHT © FSTC Limited 2006 Page 3 of 16 Islamic Art as a Means of Cultural Exchange November 2006 Figure 3. Plan of the Church of the Ascention in Jerusalem Source Greek and Byzantine artists were famous for their skill and ingenuity in the sophisticated art of glass mosaics. Most of the artisans who worked on the Dome of the Rock were Christians with some converts to Islam. The designs were mostly local, executed with brilliantly coloured jewel like glass pieces, mother of pearl and semi-precious stones. One such design consisting of a big vase with jewelled flowers and a border of eight pointed stars within circles can be traced to Sasanian decorative motifs (Figure 5). The eight pointed star in Islamic art first appeared in the decoration of the Dome of the Rock. Later, geometric figures such as the square, triangle, and circle formed the basis of abstract Islamic design and were used within all types of arabesque decoration. Figure 4. . Decorative forms in the Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem For the first time in Islamic architecture, calligraphy in the form of Qur'anic verses appeared on the walls of the Dome of the Rock, to construe part of the architectural decoration. As figurative imagery was forbidden in Muslim religious buildings, the artists used Qur'anic verses and quotations of the Prophet, along with stylized and abstract designs, to form architectural mosque decorations. The Dome of the Rock is a unique Islamic monument; in addition to its Christian church plan and local Byzantine decorative shapes that were favoured in Palestine, Jordan and Syria, it also features Sasanian and Coptic motifs. The usage of these various artistic traditions in a religious building attests to the tolerance of Islam not only in embracing many peoples with different cultures and artistic traditions, but more important, in accepting their cultures without undermining nor belittling them. Other than being a symbol of the forbearance of Islam, the Dome of the Rock indicates the beginning of a new cultural age. Publication ID: 619 COPYRIGHT © FSTC Limited 2006 Page 4 of 16 Islamic Art as a Means of Cultural Exchange November 2006 When Alexander the Great swept through Syria, Damascus became an important centre and remained so during the Roman and Byzantine periods. After the Muslims entered the city in 635, they had an agreement with the local Christian population to share their church to pray in. When their numbers increased due to the increasing number of new converts to Islam, there was a need for a larger and separate place, but neither Caliph Mu`awiya (661-680) nor his son Yazid (680 -683) wanted to break the treaties signed with the local population, according to which the new state was not to forcibly take over places of worship belonging to the Christians. After al-Walid I (670 + 675-715) became caliph in 705, he asked the Christians to choose another location on which to build their church, and they would be duly recompensed. Upon their refusal, he took over the church and built a mosque on its site. 3 Figure 5. Vase motif in mosaics at the Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem The Great Mosque of Damascus was built between 706 and 716 following the model of the Prophet's Mosque in Madina (Figure 6). Usually, the interior of a mosque is distributed in such a way that its pillars, columns and arcades make each of its parts a unit sufficient unto itself, which is exactly how the prayer hall of the Damascus mosque is shaped. It is a large hall measuring 148 meters by 40.5 meters that opens onto a vast courtyard (Figure 7). In the prayer hall there are three parallel aisles separated by beautiful arches that rest on reused Roman marble columns. On top of them, there is a second row of smaller columns and arches that were added to give height to the ceiling made of gold painted wooden beams. By adding new rows of columns to the aisles, the roofed prayer hall could be enlarged without changing the quality of the original space. Until then, the three aisles which made up the interior of the Byzantine church were usually placed in vertical position facing the alter and the central aisle always had a higher ceiling and was almost twice the width of the side aisles. The horizontally placed uniform aisles in the Umayyad Mosque which 4 correspond in length, width and height, were an innovation introduced by the Arabs. Figure 6. Plan of the Great Mosque of Damascus 3 4 W. Ali, p. 30. Ibid, 30 - 32. Publication ID: 619 COPYRIGHT © FSTC Limited 2006 Page 5 of 16 Islamic Art as a Means of Cultural Exchange November 2006 Architectural space in many Muslim regions expands outwards the buildings as in the vast prayer hall of the Damascus mosque which opens out onto the courtyard, letting daylight flood in through the front, hardly impeded by the screen of arcades. This space has nothing in common with the Roman and Byzantine architectural spaces which usually fold backwards and close on themselves. Figure 7. Courtyard of the Great Mosque of Damascus The Great Mosque of Damascus was one of the first mosques to introduce the mihrab, minbar, minara 5 (minaret) and maqsura that have since been incorporated in all subsequent mosques (Figure 8). Figure 8. The Bride Minaret at the courtyard of the Great Mosque of Damascus The Umayyads were influenced by the Greeks and Byzantines who paid equal attention to the decoration of a building as to its architecture. When they built the Great Mosque of Damascus, they covered the walls of the prayer hall, its facade and the columns of the courtyard portico with glass mosaics. The Emperor of Byzantium sent artists to execute intricate and beautiful mosaic patterns, and complicated figurative compositions for the Damascus mosque, as he had done when the Prophet's Mosque in Madina and the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem were built (Figure 9). Pictures of cities, houses, castles, waterfalls, rivers, plants, trees and flowers covered the walls and columns of the Mosque in the local Syrian tradition, yet, 5 While building the mosque, an underground chapel was discovered. In it a chest was found containing a human skull with the inscription: "This is the head of John, son of Zakharias". Upon seeing it, al-Walid had it placed underneath one of the pillars and erected a small elegant shrine over it, topped by a cupola, to honour the Christian saint. People still believe that Saint John the Baptist's head is buried there. Publication ID: 619 COPYRIGHT © FSTC Limited 2006 Page 6 of 16 Islamic Art as a Means of Cultural Exchange November 2006 with no human or animal figures which is evidence of the traditional source of aniconism 6 in Islam. They could be representational scenes of paradise inspired by urban Damascus as well as the lush countryside around it as a link that relates the next world to this one. 7 Within the new concept in these Byzantine inspired decorations, executed for Muslims, architectural forms and the world of plants were fully developed to become the main subject of the composition instead of being background drops for human figures (Figure 10, 11). Figure 9. Glass mosaics on the treasury in the courtyard of the Great Mosque of Damascus Until the present day, the Great Umayyad Mosque with its lavish decoration, balanced architecture and excellent workmanship makes up one of the greatest places of worship in Islam. The three most influential caliphs among the Umayyads in Spain were `Abd al-Rahman I (756-788) known as al-Dakhil (the Incomer), `Abd al-Rahman II (822-952) al-Bani (the Builder) and `Abd al-Rahman III (912961) al-Nasir (the Victorious). In order to set up a strong dynasty, `Abd al-Rahman I directed his energies towards developing his country's resources, founding a proper cultural movement and establishing peace on his borders and within his realm. He made Cordoba his capital and gradually transformed al-Andalus from a distant province of the 'Abbasid Empire into an independent state, albeit nominally paying allegiance to the Abbasid caliph in Baghdad. A major act of `Abd al-Rahman I was to build the Great Mosque of Cordoba in his capital, making it an important religious center that would rival the two mosques in the East: the Dome of the Rock and the Great Mosque of Damascus. Figure 10. Glass mosaics in the interior of the Great Mosque of Damascus 6 7 Aniconism is the ban on the representation of God in any form. Ibid, 34. Publication ID: 619 COPYRIGHT © FSTC Limited 2006 Page 7 of 16 Islamic Art as a Means of Cultural Exchange November 2006 At the beginning, Syrian architectural influences were apparent in the Cordoba mosque but they were soon absorbed by local traditions and innovations. The mixing of stone, marble and bricks produced a monument of great beauty. The alternating red bricks and white stone of the arches remind us of the Dome of the Rock, and yet in Cordoba they gained a new decorative element and lent a distinctive mood to the whole atmosphere. During the reign of `Abd al-Rahman II, the influence of Baghdadi architecture spread to mix with Syrian and Andalusian features. Among them were the painted wooden ceilings that cover the aisles of the mosque. Qayrawan was the bridge through which Iraqi influences in architecture crossed to al-Andalus and later on, through Almohads and Almoravids, came back to al-Maghrib. 8 Figure 11. Glass mosaics in the interior of the Great Mosque of Damascus Among the first architectural features to develop in al-Andalus was the horseshoe arch, although its origins are yet to be clearly established. It was believed that it had come to Spain from Syria through Egypt and Tunisia. However, the horseshoe arch is found in fifth century churches in Armenia, in the sixth century Sasanian Taq-i-Kisra in Iraq and in sixth century Visigoth Church of Santa Maria de Melque in Spain. Apparently it has been used around the Mediterranean basin since the second century. Whatever its origins, the horseshoe arch reached its apogee, both in function and design, in Muslim Spain as demonstrated in the Great Mosque of Cordoba 9 (Figure 12). Many of the capitals in the Cordoba mosque were taken from classical ruins in Spain and North Africa. Figure 12. Horseshoe arches in the interior of the Great Mosque of Cordoba 8 9 Ibid, 98. Ibid, 95-6. Publication ID: 619 COPYRIGHT © FSTC Limited 2006 Page 8 of 16 Islamic Art as a Means of Cultural Exchange November 2006 Instead of a niche in the wall or a small semi-circular chamber, the Cordoba mihrab has a large octagonal shaped chamber behind its arch (Figure 13). The unique gigantic naturalistic shell-shaped marble dome of the mihrab chamber appears for the first time in Islamic architecture in this extension and was seldom copied in Spain and Morocco during later periods (Figure 14). The origin of the shell is found in its more primitive form in Visigoth architectural decoration such as the decorative bas-relief from the Episcopal Palace in Salamanca. 10 Figure 13. Façade with glass mosaics at the Great Mosque of Cordoba Caliph al-Hakam II (961-976), who probably was the most learned among Muslim caliphs, enlarged the Great Mosque, channelled water to it in lead pipes, and brought Byzantine artists to execute its glass mosaics. The Cordoban mosaics do not depict figurative designs of fruits, jewelled vases, cities with buildings and waterfalls, such as found in the Dome of the Rock and the Great Mosque of Damascus. In Spain, all traces of Byzantine and Sasanian influences were shed and the decoration was solely composed of abstract arabesque and Kufic script. In front of the mihrab is a star shaped ribbed dome, carried by vaults and totally covered with blue, green and red glass mosaics, forming decorative patterns of stylized vegetal motifs on a golden background 11 (Figure 15). Figure 14. Shell shape inside the mihrab chamber of the Great Mosque of Cordoba However, the earliest use of mosaics in Islam goes back to 684, seven years before the building of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem when the Ka`ba, in Mecca, was restored after a fire, and glass mosaics were 10 11 Ibid, 99-100. Ibid, 100. Publication ID: 619 COPYRIGHT © FSTC Limited 2006 Page 9 of 16 Islamic Art as a Means of Cultural Exchange November 2006 brought from a church in Yemen to cover its walls. Early Arab accounts describe mosaics executed by Byzantine craftsmen sent from Constantinople and by Greek artisans living in Syria. When Caliph al-Walid Ibn `Abd al-Malik wanted to rebuild the mosque of the Prophet in Madina, he wrote to the Emperor of Byzantium who sent him ten workers who were worth a hundred, loads of mosaic material, 80.000 dinars and the chains from which the mosque lamps were to hang. 12 Figure 15. Glass mosaics in the interior of the dome in front of the mihrab in the Great Mosque of Cordoba The three most important early mosques outside Mecca and Madina: the Dome of the Rock, the Great Mosque of Damascus and the Great Mosque of Cordoba sent three clear messages: • The first declared that the Muslims came to stay and their monuments were witnesses to that. • The second was one not only of tolerance but of acceptance of other faiths and traditions through integrating various existing styles and decorative elements into such important religious monuments. • The third demonstrated that although the new faith did not denigrate the traditions of others and had actually embraced some of them, it did so according to its own beliefs and aesthetics introducing new artistic components that did not exist before in contemporary art and architecture. From the seventh to the fifteenth centuries, Islamic art and culture went through a relentless process of assimilation, pruning, re-initiation, and renewal of pre-existing traditions while simultaneously creating new artistic styles and techniques which suited the spiritual, aesthetics and physical requirements of its Arab patrons and creators. The Arab Muslims in general and the Umayyads in particular, showed their respect towards other peoples' cultural achievement by accepting what suited their belief and built on it, to come up with a truly international civilization. With the spread of `Abbasid power (750-1285), commercial activities multiplied between Baghdad and far away countries in India, China, Persia, Northern and Central Europe and Africa. The central geographic situation of Iraq helped ` Abbasid traders reach lands outside their boundaries. This commercial prosperity aided in communicating art and culture from one remote region to the other and in the exchange of artists and artisans. Due to intense commercial activities and travel, the `Abbasid style in the arts spread to most parts of the Empire. Lusterware in ceramics spread to Persia, Egypt, North Africa and al-Andalus; inlaying in metalwork was transmitted from Iraq to Central Asia, Persia, Syria, North Africa and al-Andalus; so did the Samarra bevelled style and the arabesque. Translations from Greek, Pahlavi, Sanskrit, Coptic and other 12 Ibid, 40. Publication ID: 619 COPYRIGHT © FSTC Limited 2006 Page 10 of 16 Islamic Art as a Means of Cultural Exchange November 2006 languages, into Arabic multiplied, resulting in the preservation of classical knowledge and the creation of a base on which Muslims added and improved before re-introducing it to the West, bringing about the Age of Renaissance in Europe. Among other examples of the diffusion of artistic subjects, trends and styles within the Islamic Empire as well as without, is in painting. Sasanian influences in Abbasid wall paintings are found at the Jawsaq alKhaqani palace in Samarra (Iraq) and in paintings of the Tulunid Dynasty made in the late ninth, tenth and part of the eleventh centuries. Excavations at Nishapur, in Eastern Iran, uncovered fragments of paintings in the same style. Other examples of the Samarra pictorial style are found in the ceiling paintings of the Palace Church of Palermo, in Sicily, that was built after the Norman Conquest and end of Arab rule that lasted from 827 to 1061. They are the best preserved Fatimid architectural paintings outside Egypt and cover the Cappella Palatina, the private chapel of King Roger II, completed around 1140. Although executed 300 years after the Samarra murals, the Palermo paintings follow the same basic `Abbasid style derived from Sasanian art which show the vitality of this style and the extent of its expansion. Another example is the early influence of Chinese painting on 13th century Ilkhanid miniatures that was neither doubted nor questioned and eventually seeped down into Persian, Arab, Mughal, and Turkish miniature traditions. Meanwhile the fusion of Arab, Mediterranean, Berber and Visigoth traditions in al-Andalus brought about a unique branch of Islamic art and civilization. One of its outcomes was the development of a distinctive Andalusian style of architecture called "Moorish Architecture" in the West. This style spread to countries of North Africa and was followed in the north by the Mudejar style. 13 The Muslims transferred new technologies such as sericulture and the manufacture of paper from east to west; and introduced new crafts and skills in ceramics, metalwork and woodwork. They developed knowledge in mathematics, philosophy, agriculture, veterinary science, astrology, and geography. Through the establishment of the University of Cordoba and schools of translation they introduced into Europe classical Greek thought and philosophy combined with Arabic learning. They institutionalized the art of music by establishing musical academies. The merging of Arab and indigenous Spanish music which gave birth to the muwashshah, strongly influenced the evolution of medieval European music. Figure 16. Exterior view of the Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca 13 Mudejar style is the Christian-Spanish style highly influenced by Arab artistic traditions. Its popularity continued long after the end of Muslim rule in Spain. Publication ID: 619 COPYRIGHT © FSTC Limited 2006 Page 11 of 16 Islamic Art as a Means of Cultural Exchange November 2006 Al-Andalus, Sicily and the Crusade wars constituted a bridge between the Islamic World and the West that was instrumental in bringing about the Age of Renaissance in the 14th and 15th centuries. However, when scholars mention Western civilization, they generally ground it in Judeo-Christian origins with no reference to Islamic contributions. The arabesque, which is the epitome of Islamic design in its most original ingenuity and has an obvious aesthetic value, as well as spiritual connotations including the infinity of God, is just one example of the influence of Islamic art on Europe. From the Renaissance until the nineteenth century arabesque was adopted and adapted in illuminated manuscripts and on walls, furniture, metalwork and china. In the past, Islamic art played a major role in the construction of Islamic civilization. Yet, since Muhammad Ali built his mosque in the 19th century, there had been no major monument that carried a statement to comply with our modern times. That is until the creation of Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca, designed by the French architect Michel Pinseau and completed in 1987 (Figure 16). It is the largest religious Islamic monument outside Mecca and has space for 25,000 worshippers indoors and another 80,000 outdoors. The 210-meter minaret is the tallest in the world and is visible day and night for miles around. An important result of the project was the revival of traditional arts and crafts in Morocco where 6,000 artisans worked for five years to turn raw materials into abundant and incredibly beautiful mosaics, stone and marble floors and columns, sculpted plaster mouldings, and carved and painted wood ceilings thus keeping the artistic traditions alive and useful albeit new colours were introduced to the traditional ones (Figure 17). The mosque also includes a number of modern features: it was built to withstand earthquakes and has underfloor heating, electric doors, a sliding roof, lasers which shine at night from the top of the minaret showing the qibla direction towards Mecca, and titanium, bronze, and granite are featured on the exterior facades and new and modern building technologies were utilized in the building process (Figure 18). Figure 17. Painted woodwork in the interior of the Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca Hassan II Mosque was created to stand on equal footing with the Dome of the Rock, the Great Mosque of Damascus and the Great Mosque of Cordoba among other Islamic religious monuments. 14 The purpose it was built for was to be "….part of the tradition of religious monuments, in the phases of their history, in the quest of the architectural art it consecrates by bringing it to the heights of fame, by renewing it, by 14 M.-A. Sinaceur, The Hassan II Mosque (n.d.), 13, 16. Publication ID: 619 COPYRIGHT © FSTC Limited 2006 Page 12 of 16 Islamic Art as a Means of Cultural Exchange November 2006 adapting it to the means that enable it to get free from the impact and stamp of the cities of another age." 15 Figure 18. Main prayer hall with moving ceiling at the Hassan II Mosque, Casablanca A desired outcome of the mosque was to change the status of "Casablanca known as the City of the Hassan II Mosque, (to) achieve(s) the deep rooted aspiration of imperial cities, in Morocco and elsewhere, to tell the Islam whose memory well live on forever in human memory." 16 After the edification of the Hassan II Mosque, Casablanca is henceforth consecrated, exactly like Fez and Marakesh, the city of art and culture. 17 However, Hassan II Mosque did not fulfil the main aspirations designated for it. It did not succeed in being on a par with its predecessors nor did it elevate the position of Casablanca to that of an imperial city. By examining the rationale behind this shortcoming one might understand the limitation of contemporary Islamic art as a 'two way transfer in international cultural exchange'. To start with, the Moroccan mosque glorifies a person rather than being a religious, cultural or dynastic symbol. The message that emanates from it is local. It fell short of transmitting a universal message even on a regional basis, meaning North Africa (Ifriqiya). Though it is an overwhelming example of adapting modern technologies and introducing traditional forms of Islamic art yet it could not affect the contemporary architectural development of the Islamic world because it remained within traditional architectural framework without important innovations in design. The modern technologies used in the building are invisible and do not affect the main architectural representation and it carries a local political statement that did not cross Morocco's borders. The golden age of Islamic civilization (900-1200) occurred in Baghdad, Damascus, Cairo, Cordoba, among other centres, in liberal and open-minded societies where the intellectual atmosphere grew to a great extend, independent of the religious authorities. When the West began its Renaissance the Islamic world was passing through a period of stagnation arid did not even try to learn from or catch up with Europe's Ages of Reformation, Enlightenment, or the Industrial Revolution. Instead, the Christian minorities (Armenians, Greeks and Jews) acted as intermediaries between the Islamic world and the West and through them it made limited progress in science and technology. In addition there was the Mongol invasion and other invasions from Central Asia, the deterioration in agriculture and the discovery of a new 15 16 17 Ibid, 12. Ibid, 8. Ibid, 56. Publication ID: 619 COPYRIGHT © FSTC Limited 2006 Page 13 of 16 Islamic Art as a Means of Cultural Exchange November 2006 maritime route around the Cape of Good Hope that caused the decline of the Arab Mediterranean region. All these factors brought about political instability and encouraged religious factionism and fanaticism. During the Age of Enlightenment when science was separated from religion after the French Revolution, Western concepts of equality and governance became palatable to the Muslims. Napoleon's invasion of Egypt (1798-99), albeit lasting a brief period, opened the door to European hegemony over Islamic lands, introduced European knowledge and later gave an incentive to leaders such as Muhammad Ali of Egypt to invite Western experts to help in the development of the country and simultaneously, send students on scholarships to Europe. What took place then was a rapid and widespread movement of Western technology in the Middle East between the second quarter of the 19th century and 1914. Following World War I the Islamic world was engaged in fighting colonial powers to gain independence, at the price of neglecting education. After World War II there was a surge in creating universities and schools, yet, a lack in creating proper school curricula that would encourage analytical and creative thinking instead of memorization and therefore develop progressive values such liberal thought, respect for human rights and political pluralism, as part of a foundation on which to build civil societies based on international humanistic belief. In these environments Islamic art and architecture adapted and adopted Western Renaissance and Rococo features yet without showing any consideration for Islamic aesthetics or introducing new artistic components that did not exist before in contemporary art and architecture. It had ceased to carry a message or become a cultural vehicle of communications. Eventually modern Islamic art since the mid-19th century became totally westernized and only in the second half of the 20th century there was a movement that attempted to ground contemporary Islamic art into its own cultural background: the modern calligraphic school in art. A major shortcoming of Muslim civilization today is its technological inadequacy that it has to work around. Some might claim that the West refuses to share with us its technological information, this might be partly true, however most of the Islamic world lack the basic requirements for what might be a semblance of modernity, such as free access to the internet and the widespread use of computers among school and university students. In some countries the reason is security, to safeguard authoritarian systems, while in others it is poverty due to corruption, fear and mismanagement. One cannot deny that the West practices double standards in dealing with the Muslim world which has led to increase in extremist religious movements and terrorism whose raison d'être is to stand up to western injustice and regain national rights. An everlasting example is the Palestinian problem. On the other hand Muslims themselves practice such double standards when dealing with themselves. A major argument among Muslims is that the industrial and technological secular West has shed its spirituality in favour of materialism and we, as Muslims, are not willing to follow suit. The first part of this argument is right. Western civilization is based on materialistic principle, yet a strong code of ethics is prevalent in the West that is based on respect for human rights and democracy, including respect for the freedom of its citizens and a strong sense of civic responsibility. While in the Islamic world we still cling to the concept of spirituality without realizing that on the whole, we limit our spiritual dimension to our personal relationship with God through prayer and other worship practices while ignoring our correlation mu`amalat with our fellow men. If the Islamic world wants to develop it has to realize that the limited spiritual dimension alone Publication ID: 619 COPYRIGHT © FSTC Limited 2006 Page 14 of 16 Islamic Art as a Means of Cultural Exchange November 2006 is not enough in a physical world where Muslims have lost their ability to understand the spirituality around them. An example is the abuse of the environment that goes on in the Islamic countries, while religious and secular leaders assert that Islam is a way of life and cannot be detached from the physical world. Since the end of the last century Western civilization has taken numerous revolutionary steps in the field of information technology. The Islamic world did not participate in this transformation as contributors but was always on the receiving end, therefore we cannot even begin to fathom how far behind the West we are in its technological revolution. Instead of trying to catch up as fast as possible in a futile race, we should concentrate on education and culture. This of course does not mean that we should not introduce modern technology into our lives and turn into cave men in a modern world. Going back in time in order to recall a glorious past with all its achievements has become a nostalgic present that is crippling our future development. What is frightening is the call to regress into the past, recreate a society that was feasible fourteen centuries ago and define ourselves through our hatred of the "other". A major threat to most Muslims is the concept of a unilateral "New World Order" that is imposed by the strong "on the weak after the demise of Communism and the end of the Cold War. Such a concept should not be a threat if Muslims recognize the concept of a pluralistic world order in a pluralistic society. By concentrating on education, the arts and culture we should be able to advance in jumps and leaps because there is no shortage of talent in our part of the world. Yet artistic traditions cannot grow within the current environment in the Islamic and Arab world. If we want to develop culturally we have to free ourselves of our fear of the other, of taking the challenge, of facing reality, of understanding our problems, of embracing change, of accepting differences like our ancestors did, without apologies or regrets. We should feel free to make mistakes in order to improve, to choose to be different, to listen to the other, to open up and learn, to debate and finally to build up our lives according to the Prophet Muhammad's sunna and treat others the way we want them to treat us. Bibliography Ali, W., the Arab Contribution to Islamic Art, Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 1999. Grabar, O., the Shape of the Holy: Early Islamic Jerusalem, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1996. Grube, E., Studies in Islamic Painting, London: Pindar Press, 1995. Sinaceur, M.-A., The Hassan II Mosque, Panayrac: Editions Daniel Briand (n.d.). List of Figures Figure 1. Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem. (http://hitch.south.cx/pictures.htm) Figure 2. Plan of the Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem Source: T. Burckhardt, The Art of Islam, Language and Meaning, London: The World of Islam, 1976. Figure 3. Plan of the Church of the Ascention in Jerusalem Source: O. Grabar, The Shape of the Holy: Early Jerusalem, New Jersey: Princeton Univ. Press, 1996. Publication ID: 619 COPYRIGHT © FSTC Limited 2006 Page 15 of 16 Islamic Art as a Means of Cultural Exchange November 2006 Figure 4. Decorative forms in the Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem Source: K.A.C. Creswell, Early Muslim Architecture, Vol. 1, Part I, New York: Hacker Art Books, 1979, 258. Figure 5.Vase motif in mosaics at the Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem Source: http://www.oberlin.edu/art/images/art109/06.JPG Figure 6. Plan of the Great Mosque of Damascus Source: T. Burckhardt, The Art of Islam. Figure 7. Courtyard of the Great Mosque of Damascus Source: http://www.sacredsites.com/middle_east/syria/images/113.jpg Figure 8.The Bride Minaret at the courtyard of the Great Mosque of Damascus Source: http://galenfrysinger.com/syria/damascus09.jpg Figure 9. Glass mosaics on the treasury in the courtyard of the Great Mosque of Damascus Source: http://www.omniplan.hu/200503-SJ/M/P1210037-Damas-MosqueCourtyard.jpg Figure 10. Glass mosaics in the interior of the Great Mosque of Damascus Source: J.-G. de Maussion de Favieres, Damascus. Baghdad, 1972. Figure 11. Glass mosaics in the interior of the Great Mosque of Damascus Source: J.-G. de Maussion de Favieres, Damascus. Baghdad. Figure 12. Horseshoe arches in the interior of the Great Mosque of Cordoba. Source: http://www.personal.psu.edu/staff/j/x/jxf17/spain2002/Cordoba%20Mosque%20interior16.JPG Figure 13. Façade with glass mosaics at the Great Mosque of Cordoba Source: http://classes.colgate.edu/osafi/images/great%20mosque%20cordoba%20mihrab.jpg Figure 14. Shell shape inside the mihrab chamber of the Great Mosque of Cordoba. Figure 15. Glass mosaics in the interior of the dome in front of the mihrab in the Great Mosque of Cordoba. Source: A. Papadopoulo, Islam and Muslim Art. Figure 16. Exterior view of the Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca Source: http://www.liuyuan.info/pix/ma/9.jpg Figure 17. Painted woodwork in the interior of the Hassan II Mosque in Casablanca Source: M.-A. Sinaceur, the Hassan II Mosque. Figure 18. Main prayer hall with moving ceiling at the Hassan II Mosque, Casablanca Source: M.-A. Sinaceur, the Hassan II Mosque. Publication ID: 619 COPYRIGHT © FSTC Limited 2006 Page 16 of 16