new perspectives on early Islamic art and architecture (George)

advertisement

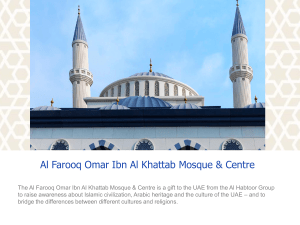

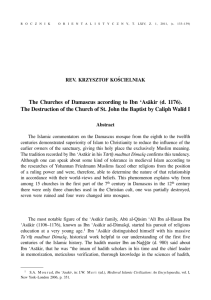

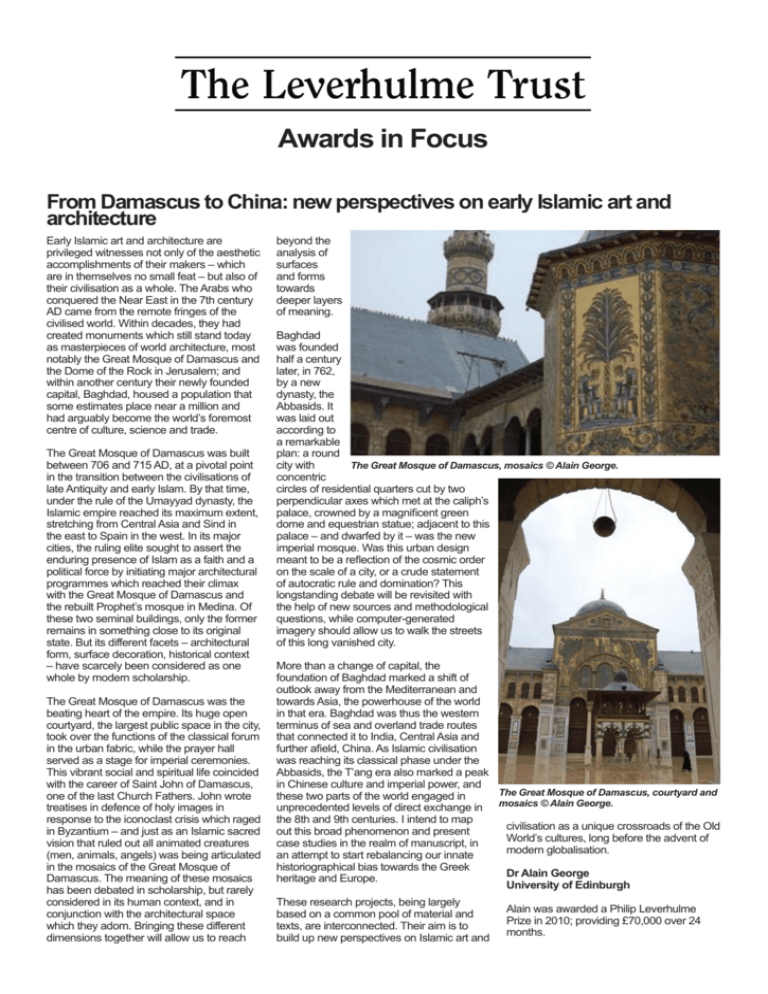

Awards in Focus From Damascus to China: new perspectives on early Islamic art and architecture Early Islamic art and architecture are privileged witnesses not only of the aesthetic accomplishments of their makers – which are in themselves no small feat – but also of their civilisation as a whole. The Arabs who conquered the Near East in the 7th century AD came from the remote fringes of the civilised world. Within decades, they had created monuments which still stand today as masterpieces of world architecture, most notably the Great Mosque of Damascus and the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem; and within another century their newly founded capital, Baghdad, housed a population that some estimates place near a million and had arguably become the world’s foremost centre of culture, science and trade. The Great Mosque of Damascus was built between 706 and 715 AD, at a pivotal point in the transition between the civilisations of late Antiquity and early Islam. By that time, under the rule of the Umayyad dynasty, the Islamic empire reached its maximum extent, stretching from Central Asia and Sind in the east to Spain in the west. In its major cities, the ruling elite sought to assert the enduring presence of Islam as a faith and a political force by initiating major architectural programmes which reached their climax with the Great Mosque of Damascus and the rebuilt Prophet’s mosque in Medina. Of these two seminal buildings, only the former remains in something close to its original state. But its different facets – architectural form, surface decoration, historical context – have scarcely been considered as one whole by modern scholarship. The Great Mosque of Damascus was the beating heart of the empire. Its huge open courtyard, the largest public space in the city, took over the functions of the classical forum in the urban fabric, while the prayer hall served as a stage for imperial ceremonies. This vibrant social and spiritual life coincided with the career of Saint John of Damascus, one of the last Church Fathers. John wrote treatises in defence of holy images in response to the iconoclast crisis which raged in Byzantium – and just as an Islamic sacred vision that ruled out all animated creatures (men, animals, angels) was being articulated in the mosaics of the Great Mosque of Damascus. The meaning of these mosaics has been debated in scholarship, but rarely considered in its human context, and in conjunction with the architectural space which they adorn. Bringing these different dimensions together will allow us to reach beyond the analysis of surfaces and forms towards deeper layers of meaning. Baghdad was founded half a century later, in 762, by a new dynasty, the Abbasids. It was laid out according to a remarkable plan: a round The Great Mosque of Damascus, mosaics © Alain George. city with concentric circles of residential quarters cut by two perpendicular axes which met at the caliph’s palace, crowned by a magnificent green dome and equestrian statue; adjacent to this palace – and dwarfed by it – was the new imperial mosque. Was this urban design meant to be a reflection of the cosmic order on the scale of a city, or a crude statement of autocratic rule and domination? This longstanding debate will be revisited with the help of new sources and methodological questions, while computer-generated imagery should allow us to walk the streets of this long vanished city. More than a change of capital, the foundation of Baghdad marked a shift of outlook away from the Mediterranean and towards Asia, the powerhouse of the world in that era. Baghdad was thus the western terminus of sea and overland trade routes that connected it to India, Central Asia and further afield, China. As Islamic civilisation was reaching its classical phase under the Abbasids, the T’ang era also marked a peak in Chinese culture and imperial power, and The Great Mosque of Damascus, courtyard and these two parts of the world engaged in unprecedented levels of direct exchange in mosaics © Alain George. the 8th and 9th centuries. I intend to map civilisation as a unique crossroads of the Old out this broad phenomenon and present World’s cultures, long before the advent of case studies in the realm of manuscript, in modern globalisation. an attempt to start rebalancing our innate historiographical bias towards the Greek Dr Alain George heritage and Europe. University of Edinburgh These research projects, being largely based on a common pool of material and texts, are interconnected. Their aim is to build up new perspectives on Islamic art and Alain was awarded a Philip Leverhulme Prize in 2010; providing £70,000 over 24 months.