3 PRIVATE CAPITAL FLOWS: FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT

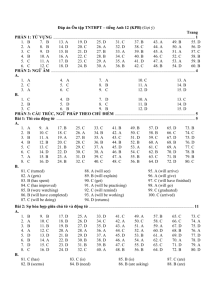

advertisement