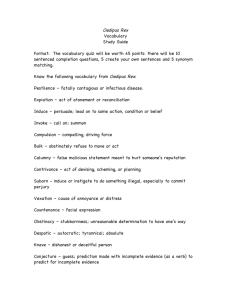

Ringing the Changes on the Oedipus-Theme

advertisement

Ringing the Changes on the Oedipus-Theme: Wagner, Fleg and the Greeks David Sansone Presented on Saturday 15 October 2005 In his contribution to The Cambridge Companion to Greek Tragedy (268) my friend Peter Burian, discussing modern adaptations of Greek tragedy, says that Enescu’s Oedipe, like Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex, “is an opera liberated from Wagnerism.” Peter is an unusually eloquent and articulate scholar, and I can only assume that he has chosen the word “liberated” deliberately. I do not propose to challenge the assumption that lies behind this choice of word . . . here. I would, however, like to take this opportunity to explore the very considerable influence Wagner has—almost inevitably—exercised on the opera we are about to hear tonight. I am not, of course, concerned with the musical influence, about which I am in no way qualified to speak. I refer, rather, to the Wagnerian libretto that Edmond Fleg supplied for Enescu to set. In his reminiscences (133), recorded by Bernard Gavoty, Enescu recalls that, initially, Fleg offered him an Oedipe in two parts, to be performed on consecutive evenings. Now, the idea of an operatic event that spills over from one day to the next is, of course, in itself unavoidably an acknowledgment of Wagnerian influence, about which Enescu felt the appropriate level of anxiety. He asked Fleg to boil down his libretto to more manageable proportions. As he says in his reminiscences (133), “I sensed in the distance the ghost of Siegfried and the graceful wraith of Pelléas.” (What, by the way, does Debussy’s Pelléas and Mélisande have to do with all this? We’ll get back to that later.) Enescu continues: “Nothing could induce me to take up once more forms and formulas whose essence had already been exhausted by geniuses of the stature of Wagner and Debussy, all the more so since there are certain resemblances between the myth of Oedipus and the saga of Siegfried.” (What exactly are those resemblances between the myth of Oedipus and the saga of Siegfried? We’ll get back to that later, too.) In response to Enescu’s request to shorten the libretto, Fleg, in his characteristically easy-going—one is tempted to say “phlegmatic”—manner obliged Enescu and presented him with a reduced version of the libretto, some ten years later, which the composer pronounced “magnifique.” One might suppose from this that the Wagnerian (and Debussyan) elements had been eliminated by decoction, but such was not the case . . . nor could it have been the case. Both Enescu and Fleg were Wagnerians to the marrow. Enescu says as much in his reminiscences (117): “J’étais wagnérian jusqu’aux moelles.” In the chapter of Enescu’s memoirs entitled “Mes dieux,” Wagner is securely enthroned between Bach and Mozart. And it is Siegfried that Enescu singles out, saying that his greatest love is reserved for the second half of Act II and the whole of Act III. In fact, Enescu introduced the music of Act III to his homeland when he included it in a series of concerts that he conducted in 1937 with the Philharmonia Orchestra. But it was not just Siegfried that Enescu knew and loved. According to the autobiography of Yehudi Menuhin, Menuhin’s revered teacher could play all of Wagner from memory on the piano. Not bad for a violinist. Edmond Fleg was not a violinist. He was a pianist. In fact, on his graduation from the Conservatoire de Genève he was awarded first prize for piano. When he was interviewed at the age of 85 he said that his only regret was that he could no longer play the piano. In his younger years, his interviewer tells us, Fleg “could play all of Wagner from memory.” As a student in Paris he would delight his friends by playing for them the last act of Tristan und Isolde. Surely Fleg and Enescu are the best-matched team of librettist and composer since the composer of Tristan collaborated with his librettist. But it is not so much the musical elements of Wagner’s operas that inspired Fleg’s libretto as the dramatic. (I hesitate to say “literary.”) What Fleg was studying in Paris was not music, but comparative literature, and his especial fondness was for German literature and German culture. He spent the academic year 1897–98 in Germany in order to improve his acquaintance with the German language and German literature. And later, when he returned to Paris he wrote for such periodicals as the Revue encyclopédique and the Journal des débats. His contributions regularly included pieces on foreign, especially German-language, literature. A piece from 1902, for example, lamented the fact that the work of Arthur Schnitzler was little known in France. On at least two occasions he wrote about Friedrich Schiller, once at some length about Schiller’s early works and once on “Schiller et M. D’Annunzio.” In 1903 he reviewed Der arme Heinrich, by Gerhart Hauptmann, who would win the Nobel Prize ten years later. (In the same year, by the way, Fleg reviewed The Pit by Frank Norris.) Fleg, at this time, thought of himself as a student of German culture; he says in his Why I Am a Jew of 1928, after he had reconnected with his Jewish roots, “I regretted my years at college spent in the study of philosophy, Germanic culture and comparative literature” (34). So, Fleg was intimately familiar with Wagner’s music and was a devoted student of German literature and culture. Is it possible to point to any concrete evidence that Fleg’s libretto was influenced by Wagner’s music-dramas? I think there is. To begin with, as I mentioned earlier, the very idea of a sequence of operas in which the story develops from one evening’s performance to the next is fundamentally Wagnerian. (Are there other examples?) Indeed, the notion of telling the Oedipus-story by including material from two of Sophocles’ tragedies—although those tragedies were not intended to form part of one connected tetralogy—is a reminder that Wagner’s Ring was itself designed on the model of a fifth-century Greek tragic tetralogy. In the event, Fleg’s original plan was significantly modified, and the resulting Oedipe became a single opera of modest, non-Wagnerian proportions, but the original intention, of combining the plots of Oedipus Tyrannus and Oedipus at Colonus, along with much background material, was retained. And it is on that background material that I would like to focus, because that is where Fleg had the greatest freedom to depart from his immediate source. Acts III and IV reproduce fairly closely the action of Sophocles’ two Oedipus-plays. But the events of Act II, in particular, the solving of the Sphinx’s riddle and the killing of Laius, while they are often referred to in the ancient sources, are not dramatized by any of the ancient playwrights. Fleg has taken the general outline of these incidents, necessarily, from ancient sources, but some of the details are right out of Der Ring des Nibelungen, specifically from the second and third acts of Siegfried, which, as we have seen, were his collaborator Enescu’s favorites. The scene in Act II of Oedipe, in which Oedipus encounters and kills Laius, takes place, as the Greek sources require, at a crossroads where three paths meet. Fleg has © David Sansone 2 added to this a “heavy, stormy atmosphere” (“Atmosphère lourde, orageuse”) and a rocky crag (“un rocher . . . escarpé”), to which the Shepherd leads his flock and from which he witnesses the murder of Laius. Even less-than-perfect Wagnerites will recall that this is very much like the setting of Act III of Siegfried: “A wild spot at the foot of a rocky mountain which rises precipitously at the back on the left. Night, storm, lightning and violent thunder.” (“Wilde Gegend am Fuße eines Felsenberges, welcher links nach hinten steil aufsteigt. Nacht, Sturm und Wetter, Blitz und heftiger Donner.”) The first words Siegfried sings when he enters this forbidding scene are a comment on the disappearance of the Forest Bird that had led him to this point (“Mein Vöglein schwebte mir fort!”). A more ominous avian reference occurs in Oedipus’ opening words when he reaches the crossroads in Fleg’s libretto: “Where am I? The raven crows.” (“Où suis-je? Le corbeau crie.”) Later, Oedipus’ killing of Laius and his attendants is accompanied by lightning and thunder, just as thunder and lightning occur at the moment when Siegfried, who is unaware of the identity of the figure who is blocking his path, hacks the Wanderer’s spear in two. The Wanderer, of course, is not Siegfried’s father, but his grandfather; still, the “Oedipal” action of the boy Siegfried, who is, after all, on the way to marry, not his mother but his aunt, are all too obvious. Now, it is true that some of the same elements can be found in Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s Ödipus und die Sphinx, published in 1906: the rocky crags, the lightning and thunder. Given Fleg’s interests it is likely that he was familiar with von Hofmannsthal’s fascinating text. In fact, Fleg and von Hofmannsthal make an interesting pair: Both men were born in 1874 and both were, among other things, successful playwrights; von Hofmannsthal was a native German-speaker with a doctorate in French philology while Fleg was a Francophone specialist in German literature. It is possible that Fleg’s Oedipus was influenced by von Hofmannsthal’s (which itself may have felt the influence of Wagner’s Siegfried). It is also possible that both dramatists were independently reflecting an awareness of the Oedipal character of Wagner’s extravagant Bühnenfestspiel. That the latter is the case is strongly suggested by some further connections between Fleg’s Oedipe and Wagner’s opera Siegfried. The scene in which Laius is killed is immediately followed in Fleg’s libretto by the scene in which Oedipus encounters the Sphinx. Before Oedipus enters, we see the Sphinx, asleep, and we see and hear the Watchman, who reassures the citizens of Thebes that, as long as the Sphinx is asleep, the citizens can rest peacefully. Enescu’s music for the Watchman is, perhaps inevitably, reminiscent of that for the Nachtwächter in Wagner’s Meistersinger. But why has Fleg included a Watchman in his libretto in the first place? And why, indeed, has he put his Sphinx to sleep? This is by no means a traditional feature. On the contrary, the Sphinx is herself traditionally a watchful guardian, both in Egyptian iconography and in Greek myth. Here is how our own Will Regier begins Chapter One of his beautiful Book of the Sphinx: “In ancient Egypt, Syria, and Greece, Sphinxes guarded gates of temples and cemeteries, perched on high columns, came in storms of wings and claws, and perfumed air like poison. Up the Nile, down the Euphrates, and all around the Mediterranean, they were thought to be supernaturally vigilant and wise.” Surely the story of a monster who accosts passersby to demand either the answer to a riddle or the traveler’s life requires a wide awake monster. But Fleg’s Sphinx is fast asleep, and apparently if Oedipus had only kept his mouth shut he could have walked right past her on his way to Thebes. In fact, he doesn’t even notice the © David Sansone 3 sleeping creature until the Watchman tells him to stop his singing or he will arouse the frightful monster. Again, I think the presence of these curious features can be explained with reference to the pervasive influence of the Ring. In Act II of Siegfried, before the youthful hero can win his bride he must awaken and slay the sleeping dragon into which the giant Fafner has transformed himself. Sleep is, of course, a recurring theme in Wagner’s Ring; in addition to Fafner, the following individuals are found asleep at one time or another: Fricka, Wotan, Hunding, Sieglinde, Brünnhilde, Erda and Hagen, along with the less discerning half of the audience. But the scene in which Fafner is awakened is specifically recalled by a number of features of Fleg’s text. To begin with, Fafner is a dragon, and Fleg’s libretto emphasizes to a remarkable degree the serpentine character of the Sphinx. In Greek myth the Sphinx is not at all serpentine. She is characterized as winged and as having a body partially human and partially either leonine or canine in form. She is, however, regularly considered to be the daughter of the more explicitly snake-like Echidna. (Echidna is simply the Greek word for “viper.”) But Fleg has conflated mother and daughter, apparently keeping the canonical form of the Sphinx— she has claws and (four!) wings— but giving her the name “Echidna.” When the Watchman introduces Oedipus to his sleeping adversary he says, “She is the daughter of Destiny, Echidna” (“C’est la fille du Destin, Ekhidna”). And so, when Oedipus awakens her he shouts, “Ekhidna! Ekhidna! . . . Réveille-toi!” This, surely, is intended to recall the first awakening of Fafner, by the Wanderer, in Act II of Siegfried: “Fafner! Fafner! Erwache, Wurm!” At this point, however, Fafner is not interested in being awakened, so he tells the Wanderer to go away. Along with the less discerning half of the audience, Fafner sleeps through most of Scene 2, until he is awakened again by Siegfried’s hunting horn. This time, being hungry, he decides to bestir himself so he can eat Siegfried. Instead, however, he tastes the point of Nothung, Siegfried’s invincible sword and, as he is dying, he asks who this young hero is. Siegfried, with more self-awareness than Oedipus, says, “There’s a lot that I don’t yet know, not even who I am” (“Viel weiß ich noch nicht, noch nicht auch, wer ich bin”). The dying dragon teases this bright-eyed boy who is ignorant of his own identity (“Du helläugiger Knabe, unkund deiner selbst”), and proceeds to tell the boy his own life history, now shortly to be ended, concluding with a mysterious warning: “Merk’, wie’s endet! Acht’ auf mich!” This suggests to Siegfried that Fafner may actually know something useful, but time is rapidly running out, so Siegfried gets straight to the point and asks Fafner if he happens to know who his (Siegfried’s) parents are. Since Fafner’s ability to think clearly is fading rapidly, Siegfried says, in effect, “Perhaps it will help if I tell you my name. It is Siegfried.” But Fafner has only enough strength to repeat “Siegfried” before he expires. Oedipus, of course, thinks he knows who he is and who his parents are, but he is tragically mistaken. There is, therefore, considerable irony in the way in which Oedipus confidently introduces himself to the Sphinx in Fleg’s libretto, as “The son of Polybus, Oedipus” (“Réveille-toi! C’est le fils de Polybos, c’est Oedipe qui t’appelle!”). The irony is enhanced, and the scene gains considerably in depth, when we recognize that Fleg has modeled this scene on Wagner’s encounter between Fafner and Siegfried, the boy who knows that he does not know who his parents are: In each scene a bold young hero awakens and slays a sleeping monster; in each case the encounter is witnessed by a third party: Alberich, who claims that he will keep watch as long as the gold continues to © David Sansone 4 gleam, and Fleg’s Watchman, whose sole function seems to be to tell Oedipus not to awaken the monster whom he proceeds to awaken; and each scene is immediately followed by the hero’s next adventure, the winning of his bride, a woman who in each instance is, unbeknownst to the young hero, a close relative. The incest-motif is, of course, integral to the Oedipus-story, but in the early years of the twentieth century it was Wagner’s shocking introduction of uninhibited incestuous relationships to the operatic stage that especially impressed itself on European consciousness. Oedipus engages in an incestuous relationship unknowingly and is devastated when he learns that his bride is in fact his mother. In Wagner, however, the incest between the twins Siegmund and Sieglinde is flaunted and glorified. The extent to which this relationship gripped the imagination is made clear by Thomas Mann’s extraordinary short story, “Wälsungenblut,” published in 1905. Thomas Mann was born in 1875, a year after Fleg (and Hofmannsthal), and his story was undoubtedly known to both of them. It would be interesting to know the Jewish Fleg’s reaction to Mann’s portrayal of Siegmund and Sieglinde Aarenhold as Jews. (They are, after all, like Wagner’s Siegmund and Sieglinde, members of an outcast race beloved of the gods.) But it is not only sibling incest that Wagner explores. Intergenerational incest, like that in the Oedipus-myth, is also lurking, undisguised, just beneath the surface. The relationship between Wotan and his daughter Brünnhilde is eroticised, a fact that cannot escape the notice of the jealous Fricka, who refers to Brünnhilde in Act II of Walküre as “the bride of Wotan’s wish” (“deines Wunsches Braut”). We have seen, then, that there are a number of connections, some stronger than others, between Fleg’s libretto for Enescu and Wagner’s Ring, especially Siegfried. Most of those connections have been of a relatively minor nature, but I should like to turn now to a feature that goes right to the heart of Fleg and Enescu’s opera, and that is the theme of Destiny. As we have seen, Fleg’s Sphinx is the daughter of Destiny, and the riddle that she poses to Oedipus is, “What is there that is greater than Destiny” (“plus grand que le Destin”)? As has often been noted, this version of the riddle is entirely new with Fleg and, indeed, the theme of Destiny, and particularly the idea of transcending Destiny, is a pervasive feature of the opera. I should like to suggest that this idea is derived from Fleg’s familiarity with the work of Richard Wagner and, further, that it is intended to make a strong statement in favor of the Wagnerian outlook, specifically in contrast to the outlook that we see in Debussy’s (and Maeterlinck’s) Pelléas et Mélisande. As we saw earlier, Wagner and Debussy were the two composers whose influence aroused the greatest anxiety in the mind of Enescu, as they naturally would for any operatic composer (or librettist) in Paris in the early twentieth century. A particular point of contrast between Pelléas and Wagner’s Ring, a point that would have been especially clearly focused for someone contemplating an opera on the Oedipus-theme, is the differing attitudes toward Destiny on the part of the French and German composers. The atmosphere of Debussy’s opera is heavily laden with the oppressive weight of inescapable Destiny. Indeed, the opening words of the opera, sung by Golaud, are, “I will never be able to get out of this forest!” (“Je ne pourrai plus sortir de cette forêt!”). And by the end of the evening he is still trapped in the dense forest of symbols that Maeterlinck and his accomplice Debussy have created for him. Nor is Golaud alone. All the characters are trapped in what Pelléas calls “the snares of fate” (“des pièges de la destinée,” Act IV, scene iv). Mélisande tells Golaud in Act II, scene ii that there is an © David Sansone 5 incomprehensible force that is stronger than her (“C’est quelque chose qui est plus fort que moi”) and that she senses that she does not have much longer to live. She is, of course, right about that. In Act IV, when the gates to the palace slam shut, trapping the lovers in their doom, Pelléas recognizes that they are no longer in control of their destiny: “Ce n’est plus nous qui le voulons!” Maeterlinck was fascinated by the notion of Destiny, and in 1898, after he had written Pelléas and his other early symbolist plays, he published an essay entitled Wisdom and Destiny (La Sagesse et la destinée). It is a rather tedious rehash of the ideas of the Stoic Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius and is in general undistinguished. It did, however, inspire an equally undistinguished painting, entitled “Wisdom and Destiny,” by the American artist Henry Keller, which was exhibited in the famous Armory Show in New York in 1913. In his essay Maeterlinck refers repeatedly to the “snares” of fate (“pièges”; §§ 13, 16, 38, 97) and he has several opportunities to mention Oedipus (§§ 12, 13, 16, 34, 45, 47, 49). For Maeterlinck, Oedipus is the paradigm of the doomed man, in contrast to the wise man, the sage, like Marcus Aurelius. Maeterlinck contrasts the hapless Oedipus with wise men like Marcus, Jesus or Socrates. He says (§ 12) that, if Oedipus had gotten some sage advice from one of those men, he would not have felt it necessary to put out his eyes. As proof of his contention that “the presence of a wise man renders destiny powerless” (“la présence du sage paralyse le destin”; § 13) Maeterlinck notes that truly wise men scarcely appear in drama, and he instances precisely Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannos as a play that lacks a character who can be considered a genuine sage. Later (§ 16) he ponders what might have happened had Epicurus, Marcus Aurelius or Antoninus Pius been afflicted with Oedipus’ fate. His verdict is that Antoninus Pius might indeed have been revealed as an incestuous parricide, but that this calamity would not have shattered his soul. On the contrary, it would have strengthened his inner resources, “and Destiny would have taken flight, throwing away his nets and broken weapons.” But this, of course, is precisely what is depicted in Fleg’s Oedipe. When Oedipus comes face to face with his Destiny, in the form of the Sphinx, who identifies herself to Oedipus as “your ghostly Destiny” (“ta pâle Destinée”), he alone of men is able to answer successfully her riddle, the answer being that Man alone is stronger than Destiny. It is, I suppose, possible that this idea, of representing the triumph of Man over Destiny as the central event in his libretto, occurred to Fleg as a reaction against Debussy’s Pelléas and its illustrious (but over-rated) librettist, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature while Fleg was working on the libretto for Oedipe. A certain sense of rivalry, therefore, may well have been part of what inspired Fleg. But in addition to this negative tendency, it is appropriate to look for a positive model as well and, given Fleg’s strong Wagnerian sensibilities, the likely place to look is in the work of Richard Wagner. We have already seen that a number of features of Fleg’s treatment of the Sphinx-scene are derived from Wagner’s Siegfried. I think we can look to the Ring also for the inspiration behind Fleg’s notion of Destiny. As Jeff Buller has well pointed out in his excellent Opera Quarterly article (75), “the words ‘fate’ and ‘destiny’ appear throughout the libretto of Oedipe, functioning almost as verbal equivalents to the musical leitmotivs that surround the opera’s major characters.” “Leitmotiv,” of course, evokes Wagner, and so does Fleg’s conception of Fate. © David Sansone 6 In Wagner’s Ring, the overthrow of Destiny is musically and dramatically represented on stage in the Vorspiel to Götterdämmerung, when the three Norns sing of the doom that awaits the gods of Walhalla and of the triumph of Siegfried, after which the thread of destiny snaps, leaving the Norns suddenly looking for alternative employment. For Wagner, the downfall of Destiny is intimately linked to the twilight of the gods and to the ascendancy of Man as an independent agent. Remarkably, we find exactly the same association in Fleg’s libretto for Oedipe. At the end of Act II, scene i, when Oedipus leaves Corinth forever to pursue his . . . fate, his exit-line is, “I shall arm myself with a jubilant shield to conquer Destiny, which is mightier than the gods” (“le Destin plus puissant que les dieux”). We learn later, from the very daughter of Destiny, that not only is Destiny mightier than the gods, the gods are . . . destined to be crushed by its mighty force. Indeed, the process has already begun. According to the Sphinx, before she poses her riddle to Oedipus in Act II, scene iii, Destiny “will shatter Phoebus’ lyre, will shatter the arrows of Artemis, will shatter the caduceus of Hermes and Athena’s spear.” “Already,” she continues, “Uranus and Cronus have fallen from the stars, and soon, mighty Zeus in his turn, languishing in Destiny’s fatal grasp, will come crashing down in the night.” Those happy listeners who have stayed awake during the third scene of Act I of Götterdämmerung will be reminded of Waltraute’s pathetic description of Wotan, the Germanic equivalent of Zeus, fading away in Walhalla, sitting silent on his throne, with the splinters of his shattered spear in his hand, morosely awaiting “Das Ende, das Ende,” which he had envisioned already in Act II of Die Walküre, some hours before. Wotan’s spear had been shattered, not by Destiny but by the fearless free-agent Siegfried whose defeat of Fafner, as we have seen, is the model for Oedipus’ conquest of the Sphinx. Fleg’s Oedipus, like Wagner’s Siegfried, is also fearless. In Act IV of Oedipe, the hero says to the divine Eumenides, “I no longer fear anything under the sun” (“je ne crains plus rien sous le ciel”). Not that he had been fearful before: In Act II he had boldly awakened and defeated the Sphinx, fulfilling the wish of Laius in Act I, that he grow up to be, like Heracles (and, incidentally, like Siegfried), unacquainted with fear (“ignorant l’effroi”). As in Wagner’s Götterdämmerung, so in Oedipe, the gods’ time has come and gone and purely human values are elevated to take their place. In the former it is Brünnhilde’s redemptive love and her renunciation of divine status, in the latter it is Oedipus’ consciousness of his own innocence and his recognition of his status as a free agent. To a certain extent, these aspects of the figure of Oedipus can be derived directly from Sophocles’ Oedipus at Colonus, which serves as Fleg’s model for Act IV of his libretto. But in the work of the pious Sophocles there is, of course, no question of exalting human agency and personal innocence above the level of the gods. That is to be found in the work of Richard Wagner, and not only in his music-dramas. In his treatise Oper und Drama (1852) Wagner gives the theoretical background to his dramatic compositional technique. It is not easy going, and I couldn’t summarize it for you even if I had more than five minutes remaining in my allotted time. What is directly relevant to us, however, is that it is precisely the Oedipus-myth that Wagner turns to, in Chapter III of Part II, as preparatory to his working-out of the characteristics of the New Form of Drama. For Wagner, Oedipus is the exemplary specimen of “the spontaneous essence of individuality” (“das urzeugende Wesen der Individualität”). His supposed “crimes” were merely the unrestrained expression of “the inner necessity of his nature” (“die innere © David Sansone 7 Naturnotwendigkeit”), which is Wagner’s definition of what the Greeks regarded as Fate. The killing of Laius was merely justifiable self-defense; in marrying Jocasta Oedipus, like Jocasta, was simply “acting unconsciously in accordance with the natural instinct of the purely human Individual.” “How significant, therefore,” exclaims Wagner, “that it was precisely this Oedipus who solved the riddle of the Sphinx!” For no one knew better than Oedipus the inner necessity of the nature of Man, and “Man,” of course, is the answer to the riddle. But, so far from being rewarded for his understanding of and his acting in accordance with “die innere Naturnotwendigkeit,” Oedipus suffers exile and self-inflicted blindness when his “crimes” are revealed. The reason for this, according to Wagner, is that the ancient Greeks failed to understand the nature of Fate, and sought to free themselves from its constraints with recourse to “the arbitrary political state.” This arbitrary political state, according to Wagner, has now become our Fate, from which we have to free ourselves, by means of “the physical vital impulse of the Individual” (“im physischen Lebenstriebe des Individuums”), exemplified so well by Oedipus. The overthrow of the arbitrary political state that Wagner envisions in Oper und Drama is not the direct, overt action that got the youthful Wagner into trouble with the law in 1849. Rather, it is a more radical, subversive activity, in which the poet and dramatist (i.e. Richard Wagner) must take a leading role. Part III of Oper und Drama is devoted to “the poetic and musical art in the drama of the future,” which has just been prepared for by Wagner’s discussion of the Oedipus-myth and by the call to overthrow the modern version of Fate by restoring the autonomy of the individual. When the Wagnerian Edmond Fleg was asked to produce a libretto for an opera based on the Oedipus-myth, it was inevitable that he should think in Wagnerian terms. He was, after all, the poet and dramatist of the future whose work Wagner’s treatise envisioned. The Zionist Fleg did not advocate the overthrow of the arbitrary political state, nor was he the revolutionary political figure that Wagner saw himself as. But he was sufficiently impressed with Wagner’s vision of a hero who is freer than the gods that he modeled his Oedipus to some extent after Wagner’s free and fearless Siegfried. Fleg’s originality, paradoxically, consists in his taking this Wagnerian vision of a free and spontaneous agent and restoring him to his original, Sophoclean roots. He does this not only by embodying this vision precisely in the figure of Oedipus, who had served as Wagner’s exemplar but whose story Wagner could not and would not dramatize. He does it by stripping away the intrusive political framework that led Wagner to shift his focus away from the figure of Oedipus and on to that of Antigone, who becomes, for Wagner, the true agent of the downfall of the arbitrary political state and who served as Wagner’s model for Brünnhilde. Fleg ignores the story dramatized in Sophocles’ Antigone, which is often regarded as concerning itself with the conflicting interests of state and individual. Instead, Fleg bases Act IV of his libretto on the equally Sophoclean precedent of the Oedipus at Colonus. This makes for a more coherent drama, by focusing throughout on the figure of Oedipus. One can’t help feeling that Richard Wagner, whose music-dramas, though expansive, are dramatically coherent, would have approved. © David Sansone 8