RECONSTRUCTION

advertisement

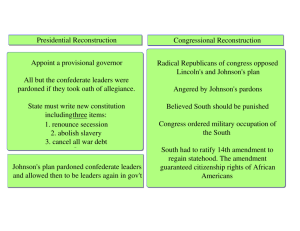

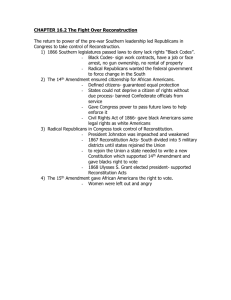

RECONSTRUCTION 1865-1877 PRESIDENTIAL RECONSTRUCTION 1. Lincoln’s Ten Percent Plan Lincoln suggested a basis for Reconstruction in a Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction issued on December 8, 1863. His Ten Percent Plan proposed a generous settlement. Lincoln offered a full pardon (except for high ranking Confederate leaders) to Southerners who pledged loyalty to the Union and to the Constitution. Southern states in which 10 percent of the 1860 electorate took such an oath and accepted emancipation would be restored to the Union. PRESIDENTIAL RECONSTRUCTION Lincoln’s Ten Percent Plan Lincoln concluded his Second Inaugural Address by promising “malice toward none, with charity for all.” He pledged “to bind up the nation’s wounds” and strive for “a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.” We will never know if Lincoln could have fulfilled his inspiring pledge. Just over a month later, John Wilkes Booth assassinated Lincoln while he was watching a play at Ford’s Theater in Washington. PRESIDENTIAL RECONSTRUCTION 2. Johnson’s Plan Lincoln’s tragic death placed the burden of reconstructing the South on the untested shoulders of his former Vice-President, Andrew Johnson. Johnson issued his own Reconstruction Plan in May, 1865. Like Lincoln, Johnson offered amnesty to most Confederates who took an oath of loyalty to the Union. High officials and wealthy planters had to apply for a presidential pardon. Whites in each Southern state could then elect delegates to a state convention. The convention had to repeal all secession laws, repudiate (take back) Confederate war debts, and ratify the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery. PRESIDENTIAL RECONSTRUCTION 3. Southern resistance All of the Southern states soon complied with Johnson’s plan. Moderate Republicans hoped the restored governments would act responsibly and treat their former slaves fairly. That did not happen. Resentful and intransigent (unyielding) white Southerners called for a renewal of laws to control the freed black population. Newly elected state legislatures promptly enacted laws known as Black Codes designed to limit the rights of the newly freedmen. The codes circumscribed (limited) the socioeconomic opportunities open to black people. For example, the codes barred blacks from owning land, marrying whites, and carrying weapons. They were forced to return to farm labor under conditions reminiscent of slavery. PRESIDENTIAL RECONSTRUCTION Southern resistance Racial tensions soon erupted into violent riots in Memphis and New Orleans. Mob violence in these cities claimed the lives of 80 African Americans and 5 whites. Rioter looted and burned hundreds of black homes, churches, and schools. The new Johnson state governments provided further evidence that the South remained unrepentant. When Congress reconvened in December 1865, a large number of former Confederate politicians and military officers were waiting to take seats in the House and Senate. RADICAL RECONSTRUCTION 1. Congress versus President Johnson The Republican-dominated Congress refused to admit the senators and representatives elected by the Southern states., Congress formed a Joint Committee on Reconstruction. The Committee recommended a Civil Rights Act to clarify the rights of freed slaves. The act states that blacks were citizens who had the same civil rights as those enjoyed by whites. Congress passed the bill in March 1866. Johnson vetoing the bill. He claimed it was an unwarranted extension of federal power that would “foment discord among the races.” Johnson’s veto galvanized (energized) the Republicans. They successfully overrode the presidential veto. This marked the first time Congress had prevailed over a veto of a major piece of legislation. It also marked the beginning of a two-year struggle between Congress and President Johnson that ended with an impeachment trial. RADICAL RECONSTRUCTION 2. The Fourteenth Amendment The Republican majority in Congress feared that Johnson would not enforce the Civil Rights Act. They also worried that the courts would declare the law unconstitutional. These concerns prompted Congress to pass the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution in June 1866. The Fourteenth Amendment overturned the Dred Scott decision by declaring that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States…are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” RADICAL RECONSTRUCTION The Fourteenth Amendment The amendment also gave the federal government responsibility for guaranteeing equal rights under the law to all Americans. The amendment prohibited the states from depriving “any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction equal protection of the laws.” The Fourteenth Amendment intensified the struggle for power between President Johnson and Congress. Saying that blacks were unfit to receive “the coveted prize” of citizenship, Johnson urged state legislatures in the South to reject the amendment. He also vigorously campaigned Congressional candidates who supported his policies. Johnson’s strategy backfired. Outraged voters repudiated the President’s policies by giving the Republicans a solid two-thirds majority in both houses of Congress. RADICAL RECONSTRUCTION 3. The Radical Republicans The victorious Republicans returned to Congress in an angry and determined mood. Led by Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania and Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, the Radicals now controlled Congress. They were resolved to punish the former Confederate states and protect the rights of black citizens. The Reconstruction Act of 1867 eliminated the state governments created by Johnson’s plan. It divided the South into five military districts, each under the command of a Union general. In order to be readmitted into the Union, a state had to approve the Fourteenth Amendment and guarantee black suffrage. The growing rift between the Radical Republicans and the President deepened when Johnson vetoed the Reconstruction Act. Congress immediately overrode his veto. RADICAL RECONSTRUCTION 4. The impeachment crisis Although he had been rejected by the electorate and humiliated by Congress, Johnson remained defiant. He undermined the Radical program by appointing generals who obstructed the implementation of the Reconstruction Act. Congress escalated the crisis by passing the Tenure of Office Act. It required Senate consent for the removal of any official whose appointment had required Senate confirmation. Convinced that the law was unconstitutional, Johnson fired Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, a leading Radical Republican ally. To no one’s surprise, Johnson’s provocative action prompted the Radicals to pass a resolution declaring that the President should be impeached. On February 24, 1868 the Republican-dominated House of Representatives impeached Johnson for “high crimes and misdemeanors in office,” that included violating the Tenure of Office Act. After a tense trial, the Senate failed to convict Johnson by one vote. Although Johnson escaped conviction, the trial crippled his presidency. Ten months later, voters sent the Union war hero Ulysses S. Grant to the White House. The Republicans completed their overwhelming victory by retaining two-thirds majorities in both houses of Congress. THE FIFTEENTH AMENDMENT The Fifteenth Amendment marked the last of the three Reconstruction Amendments. Ratified on February 3, 1870, it forbade either the federal government or the states from denying citizens the right to vote on the basis of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” The Fifteenth Amendment enabled African Americans to exercise political influence for the first time. Freedmen provided about 80 percent of Republican votes in the South. Over 600 blacks served as state legislators in the new state governments. In addition, voters elected 14 blacks to the House of Representatives and 2 to the Senate. Black voters supported the Republican Party loyally casting votes that helped elect Grant in 1868 and 1872. FIFTEENTH AMENDMENT While African Americans celebrated the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment, leading women’s rights activists felt outraged and abandoned. They angrily demanded to know why the suffrage was granted to ex-slaves but not to women. Julia Ward Howe and other leaders of the women’s suffrage movement finally accepted that this was “the Negro’s hour.” However, both Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton actively opposed passage of the Fifteenth Amendment. It is important to note that the South would soon find ways to circumvent (evade, get around) the amendment. For example, property qualifications, poll taxes, and literacy tests all denied blacks the vote without legally making skin color a determining factor. FROM SLAVE TO SHARECROPPER The Civil War brought freedom to the slaves. However, Reconstruction brought few freedmen the “4o acres and a mule” promised by zealous reformers. Many former slaves stayed on their old plantations because they could not afford to leave. During the late 1860s, cotton planters and black freedmen entered a new labor system called sharecropping. Under this system, black (and sometimes white) families exchanged their labor for the use of land, tools, and seed. The sharecropper typically gave the landowner half of the crop as payment for using his property. In addition to being in debt to the landlord, sharecroppers had to borrow supplies from local storekeepers to feed and clothe their families. These merchants then took a lien or mortgage on the crops. Sharecropping did not lead to economic independence. Unscrupulous (unprincipled) merchants often charged sharecroppers exorbitant (excessively high) prices and unfair interest rates. As a result, the freedmen became trapped in a seemingly endless cycle of debt and poverty. THE COLLAPSE OF RECONSTRUCTION 1. The Ku Klux Klan Southerners bitterly resented governments imposed by Radical Republicans that repealed Black Codes and guaranteed voting and other civil rights to African Americans. The years immediately following the Civil War witnessed the proliferation of white supremacist organizations. The Ku Klux Klan began in Tennessee in 1866 and then quickly spread across the South. Anonymous Klansmen dressed in white robes and pointed cowls used whippings, house-burnings, kidnappings, and lynchings to keep blacks “in their place.” The Klan’s reign of terror worked. Without the support of black voters, Republican governments fell across the South. By 1876, Democrats replaced Republicans in eight of the eleven former Confederate states. Only South Carolina, Louisiana, and Florida remained under Republican control. THE COLLAPSE OF RECONSTRUCTION 2. The erosion of Northern interest Radical Republicans had long been the driving force behind the program to restructure Southern society. Sympathy for the freedmen began to wane (fade) as these leaders died or left office. A new generation of “politicos” began to focus their attention on a series of issues that included Western expansion, Indian wars, tariffs, and railroad construction. President Grant showed little enthusiasm for Reconstruction. His administration soon became distracted by scandals and charges of corruption. In addition, a business panic followed by a crippling economic depression further undermined public support for Reconstruction. THE COLLAPSE OF RECONSTRUCTION 3. The Compromise of 1877 Disillusioned voters looked to the 1876 presidential election for a return to honest government. The Republicans nominated Rutherford B. Hayes, an Ohio governor untarnished by the scandals of the Grant administration. The Democrats countered by nominated Samuel Tilden, a New York governor who earned a reputation as a reformed by battling Boss Tweed. Tilden won a convincing victory in the popular vote and 184 of the 185 votes needed for the election. However, both parties claimed 19 disputed electoral votes in Florida, Louisiana, South Carolina, and one in Oregon. THE COLLAPSE OF RECONSTRUCTION The Compromise of 1877 Congress created an electoral commission to determine which candidate would receive the disputed electoral votes. As tensions mounted, Democratic and Republican leaders reached an agreement known as the Compromise of 1877. The Democrats agreed to support Hayes. In return, Hayes and the Republicans agreed to withdraw all federal troops from the South, appoint at least one Southerner to a cabinet post, and support internal improvements in the South. The Compromise of 1877 ended Reconstruction. The Republican governments in Louisiana and South Carolina quickly collapsed as Southern Democrats proclaimed a return to “home rule” and white supremacy.