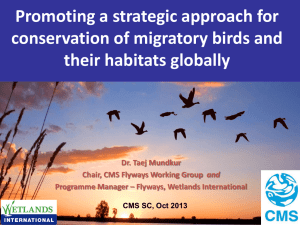

Towards a flyway conservation strategy for waders

advertisement

Towards a flyway conservation strategy for waders N.C. Davidson, P.I. Rothwell & M.W. Pienkowski Davidson,N.C., Rothwell,P.I. & Pienkowski,M.W. 1995. Towardsa flyway conservation strategyfor waders. Wader Study GroupBull.77: 70-81. Waterfowl migratoryflywaysare one of the world'sbiologicalwonders. Their maintenanceand enhancement should be a global conservationpriority. There have been, and are, a great variety of local, nationaland internationalconservationinitiativesand actionsthat contribute towards conservingmigratorywaterfowl. Many vital places on wader flyways continue, however,to be degradedand destroyeddirectlyor indirectlyby human activities. To put in place a unifyingflywayconservationprogrammea numberof key preliminarystepsare needed These includeidentifyingand filling gaps in knowledgeof how waders use the flyways; identifyingwhen and where human activitieshave an adverse impact; quantifyingsuch impacts and filling gaps in knowledge;and identifyingthe current level and efficacy of conservation action along flyways. Based on existinginformation,the paper describesexamples of flyway researchand conservationand identifiesknowngaps in knowledge. Examplesare drawn largely from the East Arianticflyway but most are just as relevantto wader flywaysworldwide. Suggestionsfor taking forwardsa co-ordinatedprogrammefor wader flyway conservationare made. N.C. Davidson & M.W. Pienkowsk?, UK Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Monkstone House, City Road, PeterboroughPE1 1JY, UK. (*present address:Royal Societyfor the Protectionof Birds, The Lodge, Sandy, Beds. SG19 2DL, UK)• P./. Rothwel/,Royal Societyfor the Protectionof Birds, The Lodge, Sandy, Beds. SG19 2DL, UK. INTRODUCTION There is considerable worldwide These coastal wetlands in western Europe of course form just one part of the links in the chain that makes up the East Atlanticflywayjigsaw. There are similar flyways around and throughmost other parts of the world (see Davidson& Pienkowski1987), and similar suitesof coastal and inland weftands, and drier habitats in urgent need of safeguard. interest in the field of waterfowl biology. Our knowledge of such aspects of a bird'slife cycle as reproductivebiology,moultingand migratorystrategiesincreaseswith each year. In our pursuit of scientificideal we should not, however, lose sightof the fact that bird migratoryflywaysare one of the biologicalwondersof the world. They are a living reminderthat we all inhabitone planet and that what may seem to be local actionscan have consequencesfor the environmentsof other biotopesand in other hemispheres. Althoughmuch conservationeffort is expendedat local and national levels, for conservationists to be successful in the objective of maintaining and enhancingthe bird populationsthat use flywaysa more holisticvision is required. It is the nature of virtuallyall major flywaysto cross many countriesand for birds to utilise different habitats at differenttimes of year. Such habits make standardapproachesto researchand conservation difficult. Conservationlaw and its implementationis applied unevenlyand levelsof research interestpatchy. Effectiveflyway understandingand conservationcan be achieved only by an integratedapproach along the whole flyway, and perhapsalso betweenflyways. Such an approach requiresconsiderablecommitment and co- Migrantwaders make some of the most spectacularof these migrations,oftentravelling non-stopin flightsof several thousand kilometres. Our interest in the detail of their annual cycles in relationto migrationsis thus both justified and, in world conservationterms, one of our highestpriorities. Whilst taking great satisfactionfrom our commonand necessaryinterestin the detail of what makes up the flywaythere is a gravedangerthat we lose sightof the whole picture. in the UK and mainlandwesternEurope much work has been done to promotethe conservationof estuariesand coastal wetlands,the winteringgroundsof so many of the same East Atlanticflyway bird populations as breed in eastern Europe and northernAsia. Indeed these migratorybird populationsand their use of internationalnetworksof siteshave oftenbeena major element in the development of conservationmeasures for wetlandecosystemsand their wildlife. ordination, but is essential. It is no longersufficientto considerthe links in the flyway chainin isolation. Researchin basic biology,the extent and impact of threats, and the conservation,protection and enhancementof speciesand habitatsare all essential to the maintenanceof the flyway. in this short paper we seek to identifythe needsto make whole flyway conservationa reality, and to move towards a structureco-ordinatingour activities in the future that will deliverthe ultimateaim - the safety, maintenanceand 70 rogersi' islan, I breeding area • stagingarea IIIIIIIIIIIII wintering area ....::• staging andwintering area :*i,.,•'* •[•;• migratory corridors Figure1. Evenforwell-researched waderswithsimplemigration systemspartsofthe worldwide flywaynetworkare poorlyestablished:a recent reviewofthe currentknowledge of the migration systemof the KnotCalidriscanutus(Davidson & Piersma1992)showsthatmanyuncertainties aboutmigrationroutesremain. enhancementof migratory bird populationsand the habitatsuponwhich they dependthroughoutthe world. Althoughwe will draw examples of the needs and processesof wader flyway conservationlargely from the East Atlantic flyway, the approach is largely applicable also to other flyways worldwide. INFORMATION a What pressuresthreaten continuedusage of each site? b. What are currentconstraintson site use by waders? c. How can be, and are, sites modified, and what are the consequencesof these modifications? d. How can this knowledgebe best usedto developand implementflyway conservationprogrammes? NEEDS Conservation actions To put in place effectiveflyway conservationaction, we need severaltypes of informationabout the flyways and the way in which wader speciesand assemblages use them. To provide this informationwe need the answers to several questionsthat can be groupedinto three broad categories,summarised as: a. What level of conservationlaw provisionexistsin differentcountriesalong a flyway? b. How can this conservation Basic biology c. How does site-based law be used to deliver nationalactions and internationalco-operation? conservation fit into the broader needs of dispersed species? a. Where are the sites used? d. How can the flyway conservationneedsof waders be linkedwiththe sustainableuse and developmentof b. What is the ecology and populationdynamics of the wader species? their habitats? c. What role does each site play in the annual cycles of each species? e. How can conservationprovisionfor wader flywaysbe enhanced, especiallywhere weak? d. How is each site related to the usage of other sites in the flyway? Althoughsome of these questionsare deceptivelysimple, as we describebelowthey can be very complexto answer. Neverthelessto provideclear and strong argumentsfor conservationactionto safeguardwaders' needs,increasinglydetailedunderstanding of how and why nationallyand internationallyimportantpopulations e. What features of each site determine how it is used? Threats and opportunities 7! of waders use their flyways, and what pressuresand impacts affect this usage. Much action is directed towards individual flyways. This is particularlyso when consideringthe detail of migrationroutes,the interdependenceof winteringsites, and the breedingbiologyand distribution of many species. Further reviewsof flywaysand reserve networksfor various groups of waterbirdsappear in Boyd & Pirot (1989) and Salath6 (1991 a). sites on a flyway - it is often informationon the links betweensites (and flyways)that is most difficultto gatherand so least known. Furthermore it is important also to consider individualsites of identifiedhigh importancefor migratory wader populationswithin the wider matrix of the relevant ecosystems,since some wader populationsare widespreadaroundthe resource(see e.g. Davidsonet al. 1991; Davidson & Stroud 1995). There has perhapsbeen more extensiveand detailed investigationof the East Atlanticflywaythan for any other wader flyway, and there have been furtherdiscoveries and reviewof wader usage of this flyway (e.g. Smit & Pierstoa 1989) since the reviews in Davidson & Pienkowski(1987), but startlinglylarge gaps remain even Conservationprogrammes,at both nationaland internationallevels, are generallydirectedtowardsthe safeguardingof individualsites, sometimeswithina broaderframework of sympatheticland-useaction. Conservationof flyway populationsof waders can be, and often is, approachedthroughthe generalsafeguardof sites used by the flyway wader assemblage. However, since each wader species has a differentset of requirements,and uses a differentsuite of sites, it is also essentialto understandflyway usage by individual species and populations. This poses challengesfor assessing how and whether sustainabledevelopmentof wetland habitats can be consistentwith flyway wader here• Internationalassessmentshave been generallyrestricted to singleflywaysand broad patternsof usage by individualspeciesor populationswithin a flyway. Yet to set conservationprioritiesin contextand to stimulate conservationaction more comprehensivelywe need also to understandworldwideflyway occurrenceand use by the relevant species. Few such assessments have been made in detail (but see Hunter et al. 1991; Lane & Parish 1991; Gill et al. 1994). As a follow-upto the broad assessment of flyway conservationfor waders (Davidson & Pienkowski1987), the Wader Study Group has more recentlypublisheda worldwidereview of the migrationsystemsof one wader species,the Knot Calidriscanutus(Pierstoa & Davidson 1992), a specieschosen because it is generally consideredto have a simple migrationsystem(Figure 1) and to be amongstthe best known migrantwaders. Certainlythe Knot has been the target of a great deal of interestand research over the last 20 years. This review has permitteda comparativeassessmentof key characteristicsin each subspeciesand also allows an appraisalof the extentto which our currentknowledge can contributeto the developmentof flyway conservation action (Table 1). conservation. THE BASIC BIOLOGY To achieve a successfulprogramme of conservationand managementof any biologicalsystem,speciesor habitat, a depth of knowledgeof the mechanicsof the system is a prerequisite. In 1987 the Wader Study Group reviewed the currentstate of our broad knowledgeof wader flyways (Davidson& Pienkowski1987). This revealedthat althoughmuch has been discoveredin recentyears about the distributionand patterns of usage of wader flyways there remained substantialgaps in knowledgefor all Table 1. Is knowledgeof the key featuresof flywayuse by KnotsCalid#scanutussufficientfor developingconservationaction? subspecies Topic canutus islandica rufa rogersi roselaari Population size& trend Breedinglocation Non-breeding location Siteroles& links ¸¸¸ ¸¸ Keyfeaturesof sites ¸¸¸ ¸¸(•) Pressureson sites ¸(•)(•) (•)(•)(•) • • (•) ¸¸ • (•) • • (•) Constraints on site use Levelof knowledge:¸¸¸ good,¸¸ fair,¸poor, © none. The resultsare alarming: the only subspeciesfor which levelsof knowledgeappear broadlyadequatefor developingconservationaction are the two (canutus and islandica)usingthe East Atlanticflyway,and evenfor these there remain uncertainties about some of the most basic informationincludingpopulationsizes and trends, 72 and the location of breeding grounds. For other subspeciesknowledgeis even poorer and for one (roselaari- probablythe scarcestsubspecies)almost nothingis known. If gaps of this magnitude exist for a well-researchedwader speciesthen it followsthat similar or greater gaps exist in the knowledgeof how other individualspeciesand populationsuse flyways. THREATS There is a clear need for further review of the current state of our knowledgeof wader flyways and their species. In addition such a review should set out to identifythose gaps in our knowledgeof these flyways and species. In particularsuch a reviewshouldset out to identifythose gaps in our knowledgeth,at hold back the processof flyway conservation.Only followingthis last step can we then start to set prioritiesfor filling gaps either through guidance to rather ad hoc continued efforts or througha co-ordinatedand funded programmeof research,whicheveris appropriateto the urgencyof need and availability of resources. For waders, the Wader Study Group can play an invaluable role (especiallythrough its r01eas the IWRB Wader ResearchGroup) in providinga forumfor bringing together informationfrom wader-workersworldwide and making it availableto an internationalaudiencethrough publicationof its Bulletin,BulletinSupplements,and new publicationseries InternationalWader Studies(IWS). Special volumes such as those providingfirst estimates of the size of breedingwader populationsin Europe (Piersma 1986), summarising international flyway conservation(Davidson & Pienkowski1987), reviewing the status of waders breeding on European wet grasslands(H0tker 1991), and the migration of Knots (Piersma & Davidson 1992) providefocusedinformation to answer the basic questionsunderlyingconservation strategy development. As the area of suitable and Wetlands Research becomes recreational activities. Rather little is known in detail about the effectsand impacts such as disturbanceto waders but a Wader Study Group BulletinSupplement (Davidson& Rothwell1993) providesa summaryof the current limited knowledgeof recreational disturbanceto waders in north-westEurope. about the location of sites and wader Waterfowl habitat for waders progressivelyreducedthe many continuinghuman activitiesare compressedinto smaller and smaller areas. Furthermore many of these activities are themselves apparentlyincreasingin scale. This leads to increasing potential pressure from 'traditional'uses such as shellfisheriesand bait-diggingas well as the wide variety of populationsin the internationalwader and waterfowl count programmes and databases co-ordinatedby the International - AND The resultsof such surveywork gives considerable concernwhen examininga flyway as a whole and assessing its future. It is the nature of bird migrationto be so dependenton chainsof suitablesitesthat pressure pointsor bottle-neckswill occur naturally. The safeguardingof these places is vital to the maintenance of the whole system (Lane & Parish 1991). Likewisethere is a very importantsourceof this key basic information SYSTEM Knowledge of the basic biology of the flyway, their species and habitats is also essentialto this second element of our suggested approach. To reach our ultimate goal of flyway conservation,maintenance and enhancement,we have to acknowledgeand understand the pressuresthat are being placedon the system both naturallyand throughthe activitiesand impact of people. Recent analyses of patterns of human activityon the estuarine wintering grounds of waders and wildfowl in Britain indicate alarming extents of habitat loss and the frequencyof occurrenceof a wide variety of potentially damaginghuman activities(Dawdson et aL 1991). Not only has, for example, at least 25% of Britain's estuarine habitat been destroyedduringthe last 2,000 years but such piecemeal land-claimfor a wide variety of human uses is continuing(despitethe many conservation designationsappliedto estuaries) at an apparentlylittle diminished rate. This affects many of the estuaries of great importancefor migrant and winteringwaders. This paper seeks not to identifyall such gaps but merely to identifythe need to address this issue in a co-ordinated fashion. TO THE OPPORTUNITIES Bureau (IWRB), the most recentlyestablishedbeingthe NeotropicalWetlands Census (NWC). In additionthe various nationaland supranationalcountand population indexingprogrammessuch as the JNCC/RSPB/BTO Birds of Estuaries Enquiry in the UK (e.g. Prater 1981; Kirbyet aL 1992) and (Meltofteet aL 1994) for the internationalWadden Sea providethe essentialbasis for developingconservationprogrammes. Such comprehensivesurvey assessmentsas Davidson et aL (1991) have been made elsewhere,especiallyin the USA (e.g. Tiner 1984), but are not yet consistently available for other major parts of flyways. It is clear, however,that similarlygreat impacts of human-generated habitatlossand degradationis widespreadthroughout many parts of the world (see e.g. Lane 1987; Smith et aL 1987; Bildstein et aL 1991; Biber & Salath• 1991; Finlayson & Moser 1991; Hunter et aL 1991; Lane & Parish 1991 ). We requirea comprehensiveexaminationof the activities that could potentiallyhave an adverse impact on migratory bird populationson the flyway. It is essential that we can assessthe likelyimpact of humans, both throughtheir existingactivitiesand via the effects of changesin our use of habitats. Such a programmeof investigationcouldinvolvealso all-encompassing problems such as global warming How will this affect bird distribution? 73 Will areas 10 Landscape/amenity I Wildlife/nature cons. J • 4 o CanaryIs.Cyprus (T) Turkey Spain Bulgaria Switzerland FranceLuxembourg Belgium UK Russia Sweden Iceland Svalbard Madeira Gibraltar Greece Albania Andorra Hungary Czech* LichtensteinPoland Is.of Man Ireland Cyprus(Gr) Azores Portugal Italy Finland Norway Romania AustriaChannel Is.Germany*'Netherlands DenmarkFaroeIs, Malta Greenland Country Figure2. The numberof differenttypesof domesticstatutorywildlifeand landscapeconservation site designations in each Europeancountry (derivedfrom informationin Grimmett& Jones 1989). and locationsof breedingand winteringhabitatschange, through for example inundationof tidal flats by rising sealevels and constrictionof Arctic tundra breedingareas consequenton possiblyaltering Arctic climate? Over Finally,on a very small scale, how does piecemealsmall land-claim or recreationor shootingimpact on birds? Answeringsuch a questioncan requiredetailed research in each location, but at least in the UK there have as yet been few impact studiesfor whichthere is adequate longtime-periodsmajor naturalpopulationdeclinesin arctic-breedingspecies have been linkedto the periodsof Pleistocene glaciation, when the area of suitable breeding habitat would have been severely restricted(Baker et aL 1994), but will additionalhuman pressureartificially depressthe size of populationsso makingthem less able to surviveperiodsof naturalstress? 'before and after' data with which to make an assessment For some countriescollectingsuch site-specific informationmay not be practicableso we need detailed studiesundertakenin such a way as to providegeneral principlesapplicableelsewhere. It is essentialthat we are able to answer questionssuch as these if we are to understandhuman impact on the flyway, and use this understandingto directefforttowards reducingany impactsfoundto be adverse. As with the basic biologythere will be clear steps in the process. There is a need to identifywhat is knownand what is requiredto be investigated. There is also a need to set out to fill the gaps in our Knowledgein a co-ordinatedand plannedfashionto providemaximumbenefitto achieving conservationand managementgoals. Internationalcooperationmeans that not everyonehas to 'inventthe same wheel': generalstudiesmade in one countrycan be applicablealso to others. This resultsin the cost-effective On a smaller scale we should be quite clear as to the impact of exploitativeactivitieslike shellfishharvesting (an activitythat has recentlycausedsubstantialimpact on waders and wildfowlin the hugelyimportantinternational Wadden Sea - C. Smit, pers. comm.), tidal power, 'amenity'and storm surge barrages,waste disposaland pollutant discharge, dock and harbour construction, marina and recreationaldevelopments,channeldredging, and drainage of inlandwetlands. For an activitysuch as shellfishfarmingand harvesting we need to know how damagingthis is to winteringbird populations.The Ramsat Conventionrequires'wise use' of our wetlands, so we need to know to what extent such use of the limited resources science. activitiesare 'wise' in the sense of ensuringsustainable use of the ecosystem. Is there a sustainablelevel of harvestingthat providesfor birdsas well as for people? Are some harvestingmethods more damagingthan others? Is there a consistencyof effect and impact of the activityon waders in differentparts of their flyway perhapsdependenton densitiesof birds,or is such impactentirelysite-specific? In additionit is vital to considerthe patternsof impactof human activitieson migratorybirds such as waders in the broader contextof the impact on the habitats on which such birdsdepend,and to understandthe human impacts on the many otherwildlifefeaturesof these places. Developingan effectiveconservationprogrammefor these habitats is the mechanism through which international 74 measures available for conservation such as the 'Ramsar' Convention and the EEC Directive on the Conservation of Wild Table 2. Internationalconservationmeasuresand agreements Birds relevant to waders and their habitats. are effected. In Europe these measures provide safeguardfor much larger areas of some habitattypes Ao Worldwide than will sites selected for their intrinsic habitat Ramsar Convention(1971) World HeritageConvention(1972) CITES (1973) Bonn Convention(1979) importanceunderthe EC Directire on the Conservationof Natural Habitats and Wild Flora and Fauna (Davidson & Stroud 1995). B. Europe/Africa/WestAsia BerneConvention(1979) EEC Wild BirdsDirective(1979) African Convention(1968) EEC Habitatsand Species Directive(1992) African/EurasianWaterbirdAgreement(BonnConvention) (1995) Understandingimpacts on habitatsand developing conservationsafeguardsfor these placesthus underpins the safeguard of migratorywaders. Waders and other migratorywaterfowlare very valuable linkinginternational networksof these sites, and the continuedpresenceof all of these networksites are essentialfor safeguardingthe populations. CONSERVING FLYWAY POPULATIONS C. East Asia/Australasia Bilateralagreements: USA, Japan, China,Australia,India,ex-USSR e.g. JAMBA (Japan-AustraliaMigratoryBirdsAgreement) OF WADERS D. Americas Protectionof MigratoryBirdsConvention(1916) Protectionof MigratoryBirds& Game Mammals Convention(1936) Western HemisphereConvention(1940) US-JapanMigratoryBirdsConvention(1976) US-USSR MigratoryBirdsConvention(1976) Western HemisphereShorebirdReserveNetwork (WHSRN) (1985) NorthAmericanWaterfowlManagementPlan (NAWMP) (1986) Many countrieshave developedconsiderable programmesof conservationeffortthat include safeguardingmigratorywaders and their habitats. Some of the site-based designationsand broader-based land use and managementare operatedthroughdomestic legislation. Others are implementedthrough the applicationof non-statutorysafeguardsuch as nature reservesmanaged by voluntaryconservationbodies such as, in the UK, the Royal Societyfor the Protectionof Birds (RSPB)• There Many countrieson wader flywaysalso apply domestic conservationmeasures in responseto international internationallaw such as the European Communities' Directire on the Conservation of Wild Birds, and the more on the Conservation of Habitats international commitmentsrelevantto waders made by countries throughoutthe world. These main international designationsare listed in Table 2. Most measures lead to the identificationand/or formal designationof sites importantto waders duringtheir annual cycle, and some requirethat these sites are the subjectof special safeguardswithin a broader matrix of measuresto safeguardbirdsthroughouttheir range and commitments conventions such as Ramsar, Berne and Bonn, or recent Directlye are thus rather numerous and Species. Other internationalmeasures derive from bilateralagreementsbetweencountriessharingmigratory bird populations(see Biber-Klemm1991). to the sustainable One international wader conservation mechanism, the use of wetlands and their birds. In a singlecountrythere can also be a multiplicityof domestic site safeguard measures. These include: Western HemisphereShorebirdReserve Network (WHSRN) has become a highlysuccessfulinternational non-statutorymechanism for raising support and awarenessof the importanceof key wetland sites on the flyways of American waders since its inceptionin 1985 (WHSRN 1990; Hunter et aL 1991). WHSRN now has four categories of reserves: hemispheric,international, regional,and endangeredspecies. By 1991 there were 12 hemispheric,four internationaland one regionalWHSRN reservescoveringabout 1.5 millionha and supporting30 millionshorebirds. Reserve membershipis entirely voluntary. Central to the networkis the understanding that the conservationand managementof shorebird habitat remains the responsibilityof the inhabitantsof the regionin which the reserveis located.Within this structurethere are three levels of site participation- ß statutorywildlife designationswhich in part are designedto implement the international commitments listed above; ß non-statutorywildlifedesignations,some of which are sites owned or managed by voluntary conservation bodies; and ß a variety of statutoryand non-statutorylandscape designations,which providefor management safeguardsin places of importanceto migratory waders. There are, for example, at least 18 differentwildlife and landscapeconservationmeasures (some statutory,some voluntary) relevantto the conservationof migratorywader sites in Britain(Davidsoneta/. 1991). Many of these have a complexrelationshipof overlappingboundaries and are selected,designatedand managed by many certified sites, dedicated sites, and secured sites - affordingincreasinglevelsof voluntaryand sometimes statutorysafeguard. 75 • Pitiill of the•,,/-• M ImpO•tln! bl•d -,,•'lT•On •outl ..' ... i We,JiemPalear•c Region A,gllement Parties oftheBonn ConvenOon Figure 3. a). Parties totheBonn Convention andthemost important migration routes (from Boere 1991); andb).theagreement areaforthe proposed Western Palearctic Waterfowl Agreement (WPWA), from theNetherlands Ministry ofAgriculture, Nature Management and Fisheries (1991) between rangestatesoftheBonnConvention. 76 states can be party to the Bonn Conventionwithoutfull membershipbeingin place. Legallybindingdirectives such as those from the EuropeanCommissionapply to only part of the range of most migratorywader populationsduringtheir annual cycle - for example only the winteringand/or staging areas of arctic-breeding species. Furthermorethe applicationof common conventionscan differ from place to place with differences either in application,or in interpretation,of international law and convention(Biber-Klemm 1991). differentorganisations. Most countriesin Europe have several categoriesof statutorywildlifeand landscape conservationmeasures, althoughthe diversityand type of designationvaries considerably(Figure 2). The developmentand implementationof both internationaland domestic conservationprogrammes for migratorywaders is not, however,uniformthroughoutthe flywaysof the world. Not all countrieshavejoined even the most worldwide of conventions such as the 'Ramsar a conventionor the Bonn Convention(Figure 3), although •1 ßI 4•population © ß IQO ha • IQQI.OOQ ha •1 1.000I0,000 ha e I0.000I00.000 ha // >IQO.OOQ ha Figure4. The distribution andsize designatedRamsarsites(wetlandsof international importance) that regularlysupportmorethan100 Knots. Filledsymbolsshowsitesthatare internationally important for a Knotpopulation (i.e. the sitesupports>1% of a biogeographical population). Notethat somesites supportKnotsin morethan one season,somesupportpopulationsof bothcanutusand islandicaKnots,and some provide onlypartialcoverageforthe coastalsitesusedby Knots. Little assessment has yet been made of the consequencesof all this variability on the extent to which wader flyways or individualwader speciesare afforded safeguardthroughouttheir annual cycle. Stroud et aL (1990) have assessedthe extentto which bird populations,includingmany waders, would be includedin the proposedSpecial ProtectionArea network (EEC Birds Directive)in Great Britain. Davidson& Piersma (1992) have recentlymade a first assessmentof the way in which designationsof wetlands of international importancehave been appliedto each Knot subspeciesat differenttimes of year (Figure 4). This shows clearlythat there are very great differencesin the extent to which Ramsar site designationshave been made for different subspecies,for differenttimes of year (breedinggrounds are particularlypoorly covered) and for different stages of the annual cycle of a single subspecies. A broader assessment for Knots worldwide safeguard(domesticand/or international)shows a similar pattern of great variability within and between populations (Figure 5). Some subspeciesare poorlysafeguardedby site designationsat most or all times of year; for others the extent of conservationcoverage is uncertain because of the uncertainties about the basic site locations for the population. In parallel to the uncertaintysurroundingthe extent to which conservationdesignationsapply to flyway populationsof waders, there is no clear flyway assessment of the extent to which all these designations are successfulin providingsafeguardsfor the populations they are designedto protect. Some informationis, however, available for individual countries, and the portentsare not good. For Britain, Davidsonet aL (1991) have describedcontinuingloss and damage to many nationallyimportantestuaries, and at rate twice that of other habitatsin Britain. The presenceof a designatedor proposed internationallyimportant site likewiseappears to of the proportionof each subspeciesat each stage in its annual cycle that is afforded some form of conservation be little deterrent 77 to further habitat loss since in 1989 over one-half of Britain'sinternationallyimportantestuaries faced land-claimproposalsthat if undertakenwouldlead to furtherloss of habitat used by waders (Figure6). Many other sites on wader flywaysworldwideare knownto be sufferinghabitat loss and facingfurtherdestructionin the Other recent internationaldevelopments(see also Salath6 1991a) includethe establishmentof an International Wadden Sea Secretariat, proposalsfor an Action Programmefor the conservationof wetlandsand waterfowlin Southand West Asia (preparedat the IVVRB/AVVB/Pakistan future. National Council for the Conservationof Wildlife 1991 Karachi Conference);an East Asia Flyway Network co-ordinatedby the Asian Wetland Bureau (AWB); and the IWRB/VVHSRN/Ducks UnlimitedNeotropicalWetlands ProgrammeøAlongside KnotCalidris canutus population coveraLe -- these are numerous islandlea national initiatives such as in the UK the RSPB'sEstuariesCampaignand SpeciesActionPlan programme,the JNCC Coastal Review(includingthe NCC/JNCC Estuaries Review), and EnglishNature's __ ½allfltfl$ Estuaries Initiative. To summarise, ensuringthe long-term survivalof any migratoryflyway needs compatible standardsto be rogersi appliedthroughoutits range,takingaccountof local situations. To determine this, as with the first two elementsof our strategy, requiresa reviewof conservationeffectivenessalong the flyway. Again this requiresco-ordinationand an aim of identifyingthe weak links in the chain, both in terms of sites and of key features of wader ecologyand flyway usage. Having undertakenthis review,a programmeof actionto correct such deficiencies could be implemented. roselaari •/•? ? 7 7 7 total species Brccdln$.qmlgralmn'winter' N ml.•Tallofi early late early late Some first steps in identifyingflyway featuresfor priority actioncan already be attempted. We have, for example, highlightedthe parts of the annual cyclefor one arcticbreedingmigrantwader for whichthere is littlesite safeguard(e.g. duringthe breedingseason)- but note that measures other than site safeguard are often more appropriatefor conservingsuchwidelydispersed populations.The prioritylistsof speciesprovidedby the Figure5• Estimatedproportions of Knotpopulations occurringwithin designatedconservation sitesduringdifferentstagesof their annualcycle. Conservation designations includebothdomestic and internationaldesignations.The lightshadingfor breeding canutusrefersto the recentlydesignatedGreatTaymyrReserve whichcoversa substantialpartof theirknownSiberianbreeding range(P. Prokosch,pers. comm.). draft Western Palearctic Waterfowl Agreement ManagementPlan (NetherlandsMinistryof Agriculture, Nature Managementand Fisheries1991) permita broader assessment Perhapspartly in responseto these perceptionsof the currentfailure of the many conservationdesignationsto safeguardmigrantwaders, there are severalnew conservationinitiativesunder development. Several of these relate to the developmentof a co-ordinatingrole through internationalmanagement plans. The IUCN, for example,establishedin 1985 its globalwetlands programme,and at aboutthe same time ICBP developed its MigratoryBirdsConservationProgramme(Salath6 1991b, c). of the characteristics of the most threatenedand vulnerablewader populationson the East Atlanticand Mediterranean/WestAsian flyways. Of the 50 wader speciesand populationsin the Western Palearctic31 (68%) are listedas threatened,rare, decreasingor vulnerable,makingwadersamongstthe higherrisk groupsof waterbirds(Table 3). Western Palearcticwaders are thus in generalin need of priority conservation action. Different'high risk'wader speciesand populationsoccur in all breedingzones from arcticto temperate,dependon all main types of winteringand stagingarea habitat and use East Atlantic and Mediterranean-WestAsian Flyways. it is interestingto note, however,also that widespread species- those with major parts of their populationusing in more than one breedingzone, non-breedinghabitat or flyway are markedly less vulnerablethan those of more restricteddistribution.This emphasisesthe importanceof range conservationfor migratorywaders. More recent,and of particularsignificanceto the flyway conservation of waders, is the African-Eurasian Waterbird Agreement(AEWA) currentlynearingcompletionunder the terms of the Bonn Convention. This excitingnew prospectiveagreement providesa mechanismfor coordinatingand linkingconservationaction on the two majorwader flywaysin the westernPalearctic(Figure2), and providesa frameworkfor developingconsistentsite safeguardsand co-ordinatedspecies/population conservationstrategies. Internationalmanagementplans are also in preparationfor some other individualwaterbird species,notablyon the White Stork Ciconiaciconia (Goriup & Schultz 1991), and the GreenlandWhitefrontedGooseAnser albifronsfiavirostds(Stroud1992). These provide useful models for potentiallywider use. 78 not seem to be suitable large areas of alternative breeding Table 3. The percentageof variousgroupsof waterfowl populations and speciesin the Western Palearcticthat believedto be in an unfavourablestate. Species and populationsare includedas in an unfavourablestate if theyare listedas threatened,rare, decreasingor vulnerablein the Western PalearcticWaterfowlAgreementDraft Management Plan (NetherlandsMinistryof Agriculture,Nature Management and Fisheries1991). habitats waders 68 divers& grebes cormorants,herons,egrets, 73 70 84 ducks rails 58 57 gulls & terns 65 on which Much is already being done to promote the conservation of migratorywaders, but many populationsremain vulnerableand face apparentlyincreasingthreats to their continued health. To put in place a conservation programme for the future, we need to take a number of key steps. These are: state a. identifywhat we do not know aboutthe basic biologyof the species and fill the gaps, highest prioritiesfirst; storks etc. swans & geese and inland wetlands so many populationsdepend for their winter survival. Indeed many of the wader populationsthat currently use these places throughout Europe are in serious decline largely through habitat destruction(H0tker 1991). Hence destructionof key elements in migratory wader flyways would mean the destructionof the species. % of spp./population in unfavourable around the coastal b. identifywhich human impacts are having an adverse impact and quantifysuch impacts along the flyway. When gaps in our knowledgeare identifiedthey need to be filled; and c. identifythe current level of conservationaction along the length of the flyway, determine its effectiveness and set about enhancing conservationaction where it is seen to be inadequate. Internationally 67with noproposals (43%) •-•--• importam estuaries 33 with no Undertakingthese steps, on a worldwide basis or even for a singleflyway, will involveconsiderablework requiring both collation and reappraisal of existing informationand collectionand collationof further informationwhere gaps ,:-.•? ;..•ais (?.1%) are identified. 19with proposals (12%) Such assessments are unlikelyto fall easily within the scope of individualorgamsations,whether national or international. Many of the major advances in our understandingof migratorywaders have come from internationalcollaborationby wader-workersand conservationists. It is appropriateto develop such future work vital for the safeguardof migratorywaders as internationalco-operativeexercises. 36with proposals (23%) We suggestthat to take this internationalflyway collaborationforward, projectscould includethe following: Figure6. Proportions of internationally important,and other,British estuariesaffectedby land-claimproposalsin 1989, from Davidsonet al. (1991). a. FUTURE DIRECTIONS CONSERVATION FOR MIGRANT WADER Migrationand flyway use reviewsfor individual species and populations,includingworldwide appraisals. A model for this could be the WSG Bulletin Supplementon Knot migrationworldwide. b. Reviewsof individualflyways,drawingin part on individualspecies reviews and how the patterns of use by many differentspecies combine to give the overall flyway picture. Elements of such reviews appear already in many guises, includingthe WSG Bulletin Supplementon flyway conservation,the various papers in Salath6 (1991), IWRB wetland inventories, the WPWA and action plan, the Canadian Wildlife Service'sSouth American shorebirdatlas (Morrison& Ross 1990), IWRB flyway populationreviews(e.g. Smith & Piersma 1989) and reviews such as NCC's Estuaries Review (Davidson et al. 1991). An internationalprojectcompilingflyway characteristics for each differentmigratorywader speciesand Wader (and other waterfowl) migratoryflyways are one of the world's biologicalwonders. The maintenance and enhancement of these populationsthrough appropriate conservationmanagementof the habitats uponwhich they depend shouldbe a global conservationpriority. Some migratoryorganisms may be able to survive even after being forcedto abandontheir migratoryhabitats through,for example, removalof key sites in a migratory network. Many migratorywader populationswould, however,seem unlikelyto be able to adopt rapidlya nonmigratorylifestyleshouldkey sites in their flyway network be removed. Such removal would prevent the populationsfrom moving betweentheir breeding and wintering grounds: arctic-breedingspecies could not survivethere through the arctic winter, and there would 79 populationin now beingdevelopedthroughthe Wader Study Group. c. InternationalWader Studies). There is great scopefor this role to continue,for examplethroughthe collaborative preparationof furtherIWS volumes. Some are alreadyin preparation,notablyon shorebirdecologyand conservationin the Western Hemisphere(from the 1991 Quito symposium),American Great Basin shorebirds,and wader researchand conservationon Europeanand North Asian flyways(based on the 1992 internationalWSG conferencein Odessa, Ukraine). Comparativeassessmentof human activities,threats and impactsfor all parts of a flyway• A model is the basicallysimple data collectionmethodology developedfor the NCC Estuaries Review (Davidsonet al. (1991), now being developedby the UK Joint Nature Conservation Review. Committee as a national Coastal For a first phase of futuredevelopmentWSG has identifiedthe followingprojects,on which collaborationis d. Reviewsof the flyway-widepatternsof conservation designationsfor individualspecies,for wader assemblagesand at differentparts of the annual cycle. e. f. sought: 1. Collationand analysisof the patternsof human Preparationof speciesconservationand management strategies,based on the types of informationgathered in a. - d. above. Such strategiesmight be developed underthe auspicesof the Bonn ConventionAEWA. There are a numberof modelsfor this approachin waterfowl,includingthe AEWA White Stork conservationmanagementplan (Goriup & Schultz 1991), and the GreenlandWhite-fronted Goose InternationalConservationPlan (Stroud 1992). A possiblefirst target for such a strategyfor waders could be the Knot,for which much factual preparatory work is available(Piersma & Davidson1992; Piersma 1994). activities and threats to wader habitats in the Western Palearctic. Preparationof wader conservationstrategiesfor differentflyways, e.g. for the East Atlantic and/or the Mediterranean/WestAsian flyways,and for countries within flyways, e.g. the recent nationalplan for shorebirdconservationin Australia(Watkins 1993); 2. Developmentof an internationalflyway conservation plan for wader speciesand populations,with the preparationof the first such plan for the Knot. 3. Encouragmentof individualsand collaborativegroups in the preparationof wader species information reviews,as the essentialprecursorto developing furtherflyway conservationplans. Two furtherspecies reviews, on Dunlins Calidrisalpinaand KentishPlovers Charaddusalexandrinus,are now being preparedfor IWS publication. We would welcome comment on these suggestions,and on how such futurewader flywayconservationmightbe best achieved. In particularwe would like to hear from anyone wishingto be involvedin such projects,and those who may be able to arrangefor the provisionof resources and to undertake g. Establishmentof a Western Palearctic wader reserve network,perhapsalongthe lines of the Western HemisphereShorebirdReserve Network. An East such work. For some of these initiativesit may be mosteffectiveto undertakepilot developmentof the approachusingsome simplerand/or betterknownsystems(suchas developing a flyway conservationfor the Knot), as well as targeting those speciesand issuesfor which urgentactionis believednecessaryand for which little is known. It is perhapsfittingthat these ideas for futurewader flyway actionwere first presentedat a uniquely international wader conference, held in Odessa, Ukraine, situatedin the heart of majorwader stagingareas on the Mediterranean/WestAsian Flyway,and at a time of year (April)when manythousandsof waderswere passing throughen route to relativelylittle-knownbreeding groundson a poorly-understood migrationroute. Many of the approachesproposedin this paperare also incorporatedin the Odessa Protocolon internationalcooperationon migratoryflywayresearchand conservation (Wader Study Group 1992), developedat that conference Many organisationsand groupscouldbe key participants in co-ordinateddevelopmentof some or all of these ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Asian-Australasian shorebird reserve network is now beingdeveloped,as are proposalsfor developing worldwide features. networks. For the Western Palearctic these could include WSG, IWRB, Ramsar Bureau,ICBP, IUCN, VVVVF(e.g. VVVVF-Wattenmeerschelle Schleswig-Holstein), the We thank David Stroud, Hermann Hdtker and Janine van Vessem for helpfuldiscussionsand commentson earlier draftsof this paper. InternationalWadden Sea Secretariat, RSPB, JNCC, the EuropeanUnionfor CoastalConservation(EUCC) and the RussianWader StudiesGroup as well as knowledgeable wader-workersthroughoutthe flyways• REFERENCES WSG has an extremelyvaluableroleto play is all this, Baker,A.J., Pierstoa,T., & Rosenmeier,L. 1994. Unravelingthe intraspecific phylogeography of knotsCalid#scanutus:a progressreporton the searchfor geneticmarkers. In: Piersma,T. Closeto the edge: energe#cbottlenecksand the evolutionof migratorypathwaysin Knots:39-45. PhD. Thesis,Universityof Groningen. since its informal international links with those active in the fieldsof wader researchand conservation in many countrieshave acted as the catalystto the collationand publicationof much vital backgroundinformationboth as materialin its regularBulletinsand compiledon special topicsin its SupplementSeries(now publishedas 8O Meltofte, H., Blew, J., Frikke, J., R0sner, & Smit, C.J. 1994. Biber,J.-P. & Salath•, T. 1991. Threats to migratorybirds. ICBP SpecialPublicationNo. 12:17-35. Numbers and distribution of waterbirds in the Wadden Sea. IWRB Publ. 34/Wader Study GroupBull.74, SpecialIssue. Biber-Klemm,S. 1991. Internationallegal instrumentsfor the protectionof migratorybirds: an overviewforthe West Palearctic-African Flyways.ICBP SpecialPublicatiot• Now12: NetherlandsMinistryof Agriculture,NatureManagementand Fisheries. 1991. Final draft of the Western Palearctic WaterfowlAgreementand ActionPlan withExplanatoryNotes and ManagementPlan. Ministryof Agriculture,Nature Managementand Fisheries(Directoratefor Nature Conservation,EnvironmentalProtectionand Wildlife Management),Gravenhage,The Netherlands. 315-344. Bildstein,K.L., BancroftG.T., Dugan,P.J., Gordon,D.H., Erwm, R.M., Nol, E., Payne,L.X. & Senner,S.E. 1991. Approaches to the conservation of coastal wetlands in the Western Hemisphere. WilsonBull. 103: 218-254. Piersma,T. 1986. Breedingwadersin Europe. Wader Study Group Bull. 48, Suppl. Boere, G.C. 1991. The Bonn Conventionand the conservationof migratorybirds. ICBP TechnicalPubl. Nos12: 345-360. Boyd,H. & Pirot,J.-Y. 1989. Flywaysandreservenetworksfor waterbirds. IWRB SpecialPublication No. 7. Piersma,T. 1994. Close to the edge: energeticbottlenecksand the evolutionof migratorypathwaysin Knots. PhD. Thesis, Universityof Groningen. Davidson,N.C. & Pienkowski,M.W. 1987. The conservationof international flywaypopulationsof waders. Wader Study GroupBull. 49, Suppl.//WRBSpecialPublicationNo. 7. Piersma,T. & Davidson,N.C. 1992. The migrationof Knots. Wader Study GroupBull.64, Suppl. Prater,A.J. 1981. EstuaryBirds. T. & A.D. Poyser,Calton. Davidson,N.C., Laffoley,D.d'A.,Doody,J.P., Way, L.S., Gordon,J., Key,R., Drake,CM., Pienkowski, M.W., Mitchell,R. & Duff, K.L. 1991. Salath•,T. (ed.) 1991a. ConservingMigratoryBirds. ICBP Techinical Publ. No. 12. International Council for Bird Nature conservation and estuaries in Great B#tain. preservation• Cambridge. NatureConservancyCouncil,Peterborough. Davidson,N.C. & Piersma,T. 1992. The migrationof Knots: conservationneedsand implications.Wader Study Group Bull. 64, Suppl.:198-209. Salath•, T. 1991b. The ICBP MigratoryBirdsConservation Programme.ICBP TechincalPubl.No. 12: 3-14• Salath•, T. 1991c. Forwardplanforthe ICBP MigratoryBirds Conservation Programme(West Palearctic-African Flyways. ICBP TechnicalPubl. No. 12: 383-393) Davidson, N.C. & Rothwell, P.I. 1993. Disturbance to waterfowl on estuaries. Wader Study GroupBull.65, Suppi. Smit, C.J., Lainbeck, R.H.D. & Wolff, W.J. 1987. Threats to coastal Davidson, N.C. & Stroud, D.A. 1995. Internationalcoastal winteringand stagingareasof waders. Wader StudyGroup Bull.49, Suppi./IWRBSpecialPublication No. 9: 24-63. conservation: conservingcoastalhabitatnetworkson migratory waterfowlflyways. In: A.H.P.M Salman,H. Berends& Mo Bonazountas(eds.), Coastal Management and Habitat Stroud,D.A., Mudge,G.P. & Pienkowski,M.W. 1990. Protecting internationally importantbirdsites. NatureConservancy Council,Peterborough. Conservation: 177-199. EUCC, Leiden. Finalyson,M. & Moser,M. 1991. Wetlands. Factson File, Oxford. Stroud, D.A. 1992. GreenlandWhite-frontedGoose Anser albifrons fiavirostrlsInternationalConservationPlan. Draftworking document:full plan,versionJanuary1992. NationalParks& Wildlife Service, Ireland/IWRB. Gill, R.E., Jr., Butler, R.W., Tomkovich,P.S., Mundkur, T. & Handel, CM. 1994. Conservation of North Pacific Shorebirds. Trans. 59th North Am. Wildl.& Natur. Resour. Conf. (1994): 63-78. [Reprintedthis WSG Bulletin]. Tiner, R.W. 1984. Wetlands of the United States: current status and recent trends. US Fish & Wildlife Service, National Wetlands Inventory. Goriup,P.D. & Schultz,H. 1991. Conservation managementof the White Stork:an international needand opportunity.ICBP Technical Publ. No. 12:97-127. Watkins, D. 1993. A nationalplanfor shorebirdconservationin Australia. RoyalAustralasianOmithol.UnionReportNo. 90. RAOU, Melbourne. Grimmett,R.F.A., & Jones,T.A. 1989. Importantbirdareas in Europe. ICBP TechnicalPub/.9. Hayman,P., Marchant,J. & Prater,A.J. 1986. Shorebirds.An identificationguide to the waders of the world. Croom Helm, London& Sydney. Western HemisphereShorebirdReserveNetwork,1990. Going global. Conservation and biologyin the WesternHemisphere. WHSRN NetworkNews 3(2-3): 1-11. H0tker, H. 1991. Waders breedingon wet grasslands. Wader StudyGroupBull. 61, Suppi. Hunter,L., Canevari,P., Myers,J.P. & Payne,L.X. 1991. Shorebird andwetlandconservation in the Western Hemisphere.ICBP Technical Publ. No. 12: 279-290. Kirby,J.S., Waters, R.Jo& Prys-Jones,R.P. 1992. Wildfowland wader counts 1990-1991. Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, Slimbridge. Lane, B.A. 1987. Shorebirdsin Australia. Nelson, Melbourne. Lane, B.A. & Parish, D. 1991. A reviewof the Asian-Australiasian birdmigrationsystem. ICBP TechnicalPubl.No. 12: 291312. 81