,PSURYLQJ3DWLHQW([SHULHQFH+&$+36

,P

P

Patient

Experience (HCAHPS) Improvement

Collaborative

C

)LHOG%ULHI

Executive Summary

One-third of UHC’s academic medical

center members ranked below the national

25th percentile in a value-based purchasing (VBP) analysis of Hospital Consumer

Assessment of Healthcare Providers and

Systems (HCAHPS) scores, conducted for

UHC’s Patient Experience (HCAHPS)

Benchmarking Project in 2010-2011. This

weak performance indicates that patients

are not receiving the level of service and

satisfaction that they need and deserve.

With less than 10% of members achieving

scores above the national 75th percentile,

many UHC member organizations risk

significant revenue loss due to VBP implementation beginning in 2013.

The benchmarking project highlighted

areas with the biggest opportunities for

improvement: responsiveness, quietness,

cleanliness, and communications. These

4 focus areas were addressed in the Patient

Barriers to Cultural Transformation

• Lack of buy-in

• Lack of accountability

• Entrenched culture and behaviors

• Competing priorities

Important takeaway about culture change:

Simply implementing a new process and

holding the staff accountable did not

truly change the culture, according to

some collaborative participants. They

found that staff members were compliant but performed new procedures as a

“checklist item” without making a real

connection with patients. Inviting patients and families to share their stories

with staff was the most powerful driver

for meaningful cultural transformation.

table of contents

Experience (HCAHPS) Improvement

Collaborative in 2011-2012; 46 teams

from 41 organizations participated.

Successful Strategies

The following successful strategies were

implemented by collaborative participants:

Establish the patient experience as a

high-priority goal, supported by senior

leaders who dedicate resources for staff

training and empowerment related to

patient satisfaction. Use data and feedback

from patients and families to identify

areas for improvement and gauge progress. Collaborate with patient and family

advisers to evaluate data, design improvement strategies, and educate staff about

patient and family needs, experiences,

and perceptions.

Focus on staff responsiveness to patient

needs, using patient and staff surveys to

better understand perceptions of responsiveness and integrating satisfaction data

into unit dashboards to highlight key

challenges. Use hourly nursing rounds

to address the 4 P’s (pain, positioning,

personal needs, and possessions), manage patient expectations, and help reduce

call-light requests. Train non-nursing staff

to support responsiveness initiatives, and

consider implementing a no-pass zone to

encourage a culture of “every patient is

my patient.”

Create a quiet healing environment by

using designated quiet hours, in-house

quiet campaigns that serve as reminders

for staff and visitors, and noise-reducing

technology. Some teams interviewed patients to better understand personal noise

concerns and offered earplugs, eye masks,

headphones, and other personal devices to

mask ambient disturbances.

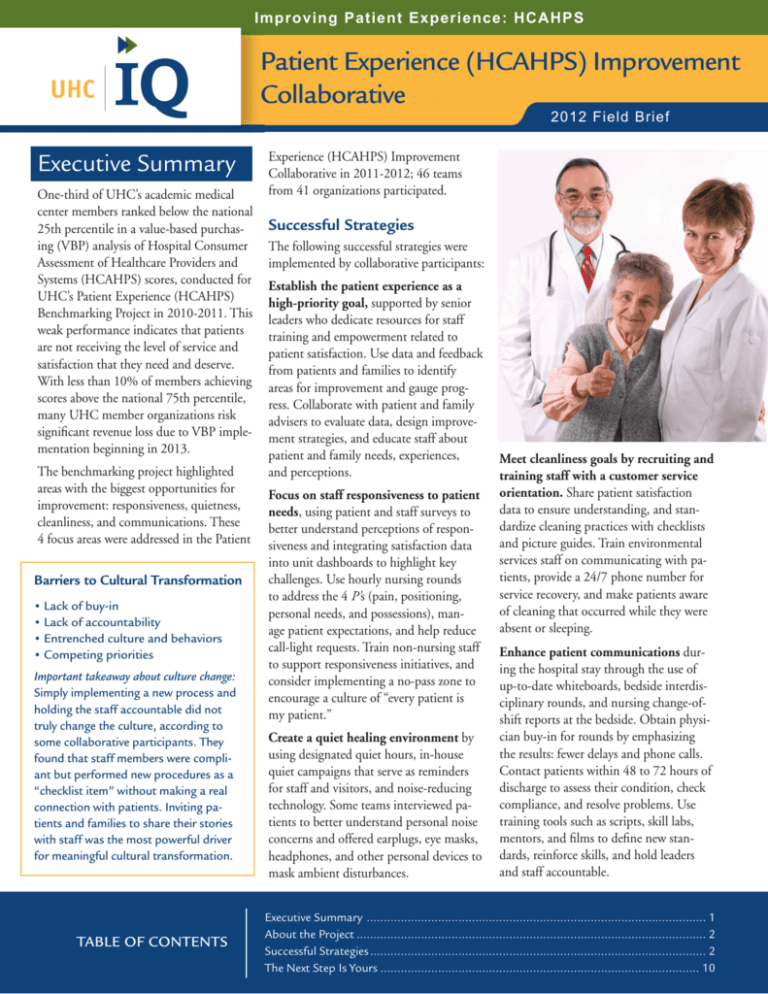

Meet cleanliness goals by recruiting and

training staff with a customer service

orientation. Share patient satisfaction

data to ensure understanding, and standardize cleaning practices with checklists

and picture guides. Train environmental

services staff on communicating with patients, provide a 24/7 phone number for

service recovery, and make patients aware

of cleaning that occurred while they were

absent or sleeping.

Enhance patient communications during the hospital stay through the use of

up-to-date whiteboards, bedside interdisciplinary rounds, and nursing change-ofshift reports at the bedside. Obtain physician buy-in for rounds by emphasizing

the results: fewer delays and phone calls.

Contact patients within 48 to 72 hours of

discharge to assess their condition, check

compliance, and resolve problems. Use

training tools such as scripts, skill labs,

mentors, and films to define new standards, reinforce skills, and hold leaders

and staff accountable.

Executive Summary ..................................................................................................... 1

About the Project........................................................................................................ 2

Successful Strategies.................................................................................................... 2

1

The Next Step Is Yours...............................................................................................

10

Improving Patient Experience: HCAHPS

About the Project

staff training and empowerment related to satisfaction. In

the collaborative, leaders used data to understand where the

patient experience needed improvements, held providers

and staff accountable for necessary changes, and recognized

and rewarded excellence as part of the culture change. Some

leaders engaged consultants to help change the organizational culture.

The Patient Experience (HCAHPS) Improvement Collaborative focused on helping UHC members implement strategies

to enhance the patient experience and improve patient satisfaction scores. A total of 46 project teams were fielded from

41 participating organizations.

Using data and patients’ stories to understand the care experience. The team from University Hospitals Case Medical

Center (UH/CMC) faced wide-ranging performance in Press

Ganey scores across different units. There were also swings

in scores due to electronic medical record implementation,

variations in census and acuity levels, and difficulties in sustaining improvements.

A collaborative process was followed, with monthly networking calls held from July 2011 through January 2012. Participants formed 3 work groups—on responsiveness, environment, and communications—to focus efforts where the most

improvement was needed. Teams shared tools, resources, and

strategies for changing processes and attitudes.

The team strove to align leadership and staff efforts to

improve the patient experience by focusing on the related

HCAHPS domains, beginning with sharing data more

frequently (biweekly) to provide a real-time snapshot of unit

performance. The team also embarked on physician and staff

education about why HCAHPS and VBP scores are important and how those metrics are affected by provider and staff

performance. In addition to data, storytelling by patients

and families at a system-wide retreat had a huge impact and

improved understanding of patients’ feelings and frustrations.

The organization has seen gains in its HCAHPS scores for

2011-2012 (Table 1).

Reasons for Joining the Collaborative

Why did the team from University Hospitals Case Medical

Center participate?

• UHC identified top performers and best practices.

• Members shared tactical plans for overcoming

common barriers.

• Members provided creative twists for implementing

•

•

best practices, such as asking physicians to alert staff

before arriving for interdisciplinary rounds.

UHC facilitated the collaborative calls and led detailed

discussions to identify solutions.

The collaborative spurred the team to develop and

execute plans with renewed clarity.

The UH/CMC team learned the importance of getting all

stakeholders, including patients and families, on the same

page and dispelling myths about the value and validity of

satisfaction scores, especially among providers.

Successful Strategies

Turning HCAHPS data into action. The executive team

at The Methodist Hospital System (The Methodist Hospital) built exceptional service into the “pillars of excellence”

and 2012 focus areas. Executive dashboards clearly show

HCAHPS performance and are accompanied by an accountability matrix and action plan that assign responsibility for

improvement target areas and define metrics for success.

Participants implemented or refined several successful strategies to improve the patient experience and related satisfaction scores.

Establish the Patient Experience as a

High-Priority Goal

Focus on Staff Responsiveness to

Patient Needs

Senior leadership focus. Collaborative participants found it

was very important for senior leaders to focus on the patient

experience. This focus was often linked with modeling the

concepts of patient- and family-centered care within the

organization. Some teams invited patients and families to

share their stories with the board and staff members to give a

more personal perspective on problems and the importance

of service excellence.

Data-driven approach. Some teams used surveys of patients

and staff to better understand perceptions about the patient

experience. This approach was particularly helpful in uncovering what staff behaviors needed to be clearly defined and

implemented.

Data were also used to conduct root cause analyses of delays

in service, and teams worked with staff and patient advisers

to establish standards. Responsiveness data were incorporated

To achieve their patient experience goals, senior leaders must

dedicate sufficient resources to customer service, including

2

Patient Experience (HCAHPS) Improvement Collaborative 2012 Field Brief

Table 1. HCAHPS Scores for University Hospitals Case Medical Center, 2009-2012

CAHPS

2009

Top Box

2010

Top Box

2011

Top Box

2012

Top Box

Rate hospital 0-10

Recommend the hospital

Cleanliness of hospital environment

Quietness of hospital environment

68.2 p

75.0 p

61.6 p

46.7 p

68.3 p

75.5 p

63.2 p

45.0 q

70.2 p

77.0 p

66.2 p

49.3 p

74.2 p

77.2 p

67.5 p

58.5p

Communication with nurses

Response of hospital staff

Communication with doctors

Hospital environment

Pain management

Communication with medicines

Discharge information

74.1 p

53.2 p

76.0 q

54.2 p

66.1 q

57.3 p

81.5 p

74.5 p

52.9 q

76.0

54.1 q

66.4 p

59.4 p

82.1 p

76.7 p

56.5 p

78.6 p

57.8 p

68.8 p

62.3 p

85.2 p

79.2 p

57.9 p

79.8 p

63.0 p

71.1 p

65.8 p

86.5 p

Source: Adapted from Vidal K, Dragon MA, Furnari R, Milter C. Improving HCAHPS by increasing communication. Presented at: UHC Patient Experience

(HCAHPS) Improvement Collaborative Knowledge Transfer Web Conference; April 16, 2012. https://www.uhc.edu/docs/49016628_UHCaseApril162012.pdf.

Accessed September 2012.

HCAHPS = Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems.

implemented, ongoing reminders and education were used to

reinforce behaviors. Unit leaders often rounded on patients

to verify that nursing rounds were properly conducted.

and reviewed in dashboard format to enhance understanding from the top down. The team from Shands Jacksonville

Medical Center, Inc., decided to revise unit dashboards to

feature responsiveness data.

To manage expectations, participants informed patients about

hourly rounds at admission. When patients realized that

someone would stop by every hour, they often waited for the

next visit to make minor requests, thus smoothing workflow.

Nurses were required to leave a phone number for sleeping or

absent patients as a way of informing them of the visit.

Current satisfaction data were regularly shared with appropriate teams to help individuals connect their behaviors to

scores. Clinical outcome measures such as falls and pressure

ulcers were also used to evaluate the success of staff responsiveness initiatives.

Getting results with the “Iowa greeting.” The University

of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics team pursued “A NOD and A

Thanks” as its hardwired communication framework, defined

as acknowledge and greet, provide name and occupation,

explain duty or task, ask if anything else can be done, and

thank the patient. This process—used in every interaction

with patients, families, and visitors—helps ensure a common

language and promotes courtesy, respect, and relationship

building.

To ensure long-term success, teams collected both patient

and employee feedback before finalizing any process changes.

The frequent use of pilots among participants helped finetune practices before broader implementation.

Hourly nursing rounds. A structured approach to rounds

was employed by participants, such as having a nurse or aide

round on each patient every hour with a special focus on

the 4 P’s: pain, positioning, personal needs, and possessions.

Some teams found that pain management and toileting assistance are patients’ top priorities and require prompt attention. The team from University of Wisconsin Hospital and

Clinics used hourly rounds to drive an 11% overall increase

in patient satisfaction scores and a 21% improvement in

toileting scores.

In addition, Iowa’s environmental services employees became

involved in rounding from 3:30 pm to 9:00 pm, engaging

patients and auditing their perceptions of daily room cleaning. The employees verify that the whiteboard has been

updated with caregivers’ names and contact information,

assist with on-the-spot service recovery, and ask about other

ways they can help, including handling requests or concerns

Creating a rounding system often required the development

and testing of new workflows by unit staff. Once rounds were

3

Improving Patient Experience: HCAHPS

The Loyola team learned several lessons: Develop a core

group of charge nurses to sustain changes. Hardwire the

supervisors. Create a process to quickly orient float staff

during challenging periods. Measure the number of call

lights both before and after the implementation of rounding,

and use a decrease in call lights as a staff motivator. Keep the

staff ’s focus on “this isn’t extra work; this is how we do our

work.” Hold charge nurses and staff accountable for behaviors

and outcomes.

related to quiet at night and other nonclinical needs, so that

the patient does not have to call a nurse. Another strategy

involves conducting hourly nursing rounds to reduce call-light

requests and keeping a paper log of visits so that patient’s

families can see evidence of rounding activity. Iowa’s inclusive

approach to managing the patient experience has increased

patient satisfaction scores, especially related to call lights and

toileting assistance.

The Iowa team learned that best practices can break down

when team members are not available and when days become

hectic. Support for hourly nursing rounds increased when

staff members understood that the number of call-light

requests can be reduced and that “rounding isn’t an extra

job, just a different way of doing the job.”

No-pass zone. To encourage a culture of “every patient is my

patient,” some teams piloted the concept of mandating that

staff cannot walk past a call light without responding. Nonnursing staff (including housekeepers and clerical staff ) were

trained to respond to minor requests or notify appropriate staff

of patients’ requests. The charge nurse or other designated

individual on each shift facilitated a prompt response to patients’ needs. For this strategy to work, staff on all shifts must

be able to easily see call lights so they can respond quickly.

Clarifying the definition of and implementing hourly

rounding. In talking with staff, the Loyola University Medical Center team discovered a disconnect in understanding

between the goal of hourly rounding and the actual practice

of rounding hourly. Some staff members believed they were

fulfilling the rounding requirement by making a quick stop

in patient rooms and asking, “Are you okay?” from the doorway. This informal behavior needed to be replaced by a more

formal and consistent rounding process.

Ongoing training. Participants found it helpful to frame

tasks as “it is the job, not an extra job” to effect culture

change. They presented staff responsiveness as critical to

patient safety, and unit-specific responsiveness data were

regularly shared so that staff members could understand the

impact (positive and negative) of their behaviors. A reduction in call lights was a desirable goal that encouraged buy-in

from staff.

To implement hourly rounds, the Loyola team first had to

change the staff ’s perception that rounds were already being

done when nurses made only a quick stop in patient rooms.

Staff education was developed and delivered by a staff nurse,

focusing on the 4 P’s and emphasizing both the benefits and

the process of rounding. Patients’ expectations about rounds

were shaped during the admission process. Staff members

were reminded about rounding through signs in patient

rooms, posters in the break room, and huddles at the start

of every shift.

Training was offered for all shifts to model behaviors and

reinforced during staff huddles and meetings. In some cases,

patient and family advisers were invited to speak to staff

about how it feels to wait for a call-light response.

Create a Quiet Healing Environment

Designated quiet hours. Participants established or recommitted to quiet hours for every shift and informed patients,

families, and staff about the importance of restful healing,

aided by a quiet environment. Patients and families were

asked to alert staff about noise issues so that they could be

resolved. The Vanderbilt University Medical Center team

even gave patients the option to use the interactive television

system in their rooms to notify staff about noise.

To encourage buy-in, the team stressed that when hourly

rounding is done well, patients are safer, their needs are better met, and nurses have more time for charting and other

duties. When nurses expressed frustration, they were given

data on the proven benefits of hourly rounding. To avoid

confusion, nurses worked with patient care technicians to

coordinate rounding hours, often with one handling odd hours

and the other handling even hours. Managers also round on

patients to validate that hourly rounding is happening in

accordance with standards.

Some participants conducted an audit to identify other

departments (e.g., housekeeping or nutrition) whose staff perform activities during quiet hours. Teams then collaborated with

these departments to arrive at noise-reducing solutions. Vendors

were also involved and asked to change pickup and delivery

times to lessen noise. Nurses were empowered to ask physicians

and others to keep their voices down during quiet hours.

The use of call lights is periodically measured and found to

be reduced, even with a higher patient census. In addition,

hourly rounding moved patient satisfaction scores from the

18th to the 55th percentile for “my needs were handled

promptly” in the pilot unit.

4

Patient Experience (HCAHPS) Improvement Collaborative 2012 Field Brief

Increasing quiet at night. As part of a Quiet at Night initiative, the Methodist team conducted a 4-week assessment in

6 pilot areas. The responses of 63 patients and 25 employees

helped the team better understand opinions about quiet areas

and provided a frame of reference for defining quiet hours. The

most bothersome noises to patients were loud talking or laughing, medical equipment, alarms, and noise from other patients

and visitors. Patients said that keeping room doors closed when

medically appropriate and not waking them for unnecessary

reasons would reduce noise and promote restfulness.

meter data will continue to be collected and assessed. Weekly

and monthly HCAHPS analysis continues to track patient

satisfaction levels against changes.

Patient unit HCAHPS scores are mixed but improving

since the Quiet at Night initiative began in October 2011.

For example, Figure 1 shows a surgical unit improving its

HCAHPS quiet-related score from 70 to more than 80 since

the initiative began. Similarly, a cardiovascular unit improved

its score from 40 to nearly 70.

The Methodist team learned that patient perceptions about

quiet may differ from staff perceptions. The team recommends conducting pilots to obtain feedback unit by unit and

using noise data to show staff how and when noise thresholds

are exceeded.

The Methodist team focused on the HCAHPS standard for

quiet at night by setting a 2012 target score of 63.8, with

70.3 considered a superior achievement; 2011 results were 61.

The team aimed to meet the very challenging decibel limits

established by the World Health Organization: 45 dB for day,

35 dB for night. The team especially wanted to address the

most common noise complaints: loud talking, televisions, cell

phones, alarms, nursing station phone calls, rolling equipment/carts, overhead paging, and construction noise.

Quiet campaigns. To emphasize the importance of a quiet

environment, some participants launched in-house campaigns to remind staff and visitors of the need for quiet.

Posters, tent cards, and other visual reminders were used to

raise awareness.

The team installed noise meters that light up when a specific

level (set at 65 dB) is exceeded. Noise reports were sent to

various departments, showing a week’s data with suggestions

on ways to lessen noise. The team plans to expand the pilot

and use noise meters in more units.

Managers were provided with tools to train staff about noise

reduction. Training was often reinforced during staff meetings and through articles posted on the hospital’s intranet.

Managers were tasked with stopping, listening, and giving

immediate feedback to staff about noise levels. Leaders

from other areas were also encouraged to round and assess

noise levels.

To counteract noise, quiet hours were standardized throughout the hospital, and education was developed and implemented to address the noise level of staff conversation. Noisy

carts were fixed to further reduce hallway noise. The team

also implemented a closed-door policy and process, when

feasible, to address patients’ wishes.

Creating and marketing quiet solutions. The University of

Michigan Hospitals & Health Centers team collaborated with

marketing staff to develop a quietness campaign, including

hallway signs (Figure 2) and tabletop cards.

Patient and staff impressions about noise will be obtained

and compared with the original benchmark level, and noise

Figure 1. Changes in HCAHPS Quietness Scores in 2 Patient Units at The Methodist Hospital,

October 2011-March 2012

Surgical Unit

Cardiovascular Unit

100

Score

80

60

40

20

0

Week

Oct ’11

Nov ’11

Dec ’11

Jan ’12

Feb ’12

Mar ’12

Source: Adapted from Hackett CJ, Cook J, Creany P. Quiet at night: The Methodist Hospital HCAHPS noise reduction initiative. Presented at: UHC

Patient Experience (HCAHPS) Improvement Collaborative Knowledge Transfer Web Conference; April 11, 2012. https://www.uhc.edu/docs/49016625_

MethodistQuietatNightInitiative41112.pdf. Accessed September 2012.

5

Improving Patient Experience: HCAHPS

Once solutions were in place, the team followed up with patient

focus groups and input from hospitalists, nurse managers, and

medical directors. Press Ganey data are shared to track results.

Figure 2. Hallway Sign for Quiet Campaign at

University of Michigan Hospitals & Health Centers

The Michigan team learned that reminder materials need to be

visually refreshed to continue to capture staff attention. Influencing long-term change, the physical building structure, and

budget constraints are constant challenges. Multidimensional

solutions are needed to produce sustainable improvements.

Noise-reducing technology. Collaborative participants made

equipment less noisy by adjusting the default alarm and volume settings on monitors and setting pagers and phones to

vibrate, not ring. Another idea was providing flashlights to the

night staff so that they could avoid disturbing patients at rest.

Participants also used measuring equipment to monitor noise

levels and then implemented several strategies:

Source: Rutherford R, Bear P. The Michigan difference: creating a clean and quiet

healing environment. Presented at: UHC Patient Experience (HCAHPS)

Improvement Collaborative Knowledge Transfer Web Conference; April 11, 2012.

https://www.uhc.edu/docs/49016626_UofMCreatingaCleanandQuietHealing

EnvironmentApril2012.pdf. Accessed September 2012.

• Changing noisy door latches and cart casters

• Using trash cans with quiet lids, door bumpers, and blackout bed curtains

•U

sing sound-absorbing materials and white-noise generators

The team’s quietness analysis (based on patient feedback)

revealed that roommates, staff behavior, and facilities and

equipment were the major sources of noise. The team

developed systematic countermeasures for each noise source,

including noise-suppression devices and process changes

(Table 2).

• Evaluating new housekeeping equipment for noisereduction potential

• Asking vendors to replace noisy equipment

Some teams offered patients earplugs, eye masks, headphones,

or pillow speakers to mask noise or reduce the volume of their

Table 2. Countermeasures for Noise at University of Michigan Hospitals & Health Centers

Noise Source

Roommates (e.g., talking, phone calls, television)

Staff behavior

Facilities and equipment

Practices (e.g., open/closed doors, floor cleaning)

Neighbors (e.g., television, loud voices, nurses in

adjoining rooms)

Countermeasures

• Headphones, earbuds, and earplugs

• Increased use of private rooms

• Hallway signs as quiet reminders

• Noise meters

• Screen savers as quiet reminders

• Door gaskets and hydraulic door closers to dampen sound

• Door latches that reduce banging

• Plastic custodial carts

• Microfiber mops

• Quiet reminders

• Different floor-cleaning time

• White-noise machines

• Headphones, earbuds, and earplugs

• Ceiling panel

Source: Adapted from Rutherford R, Bear P. The Michigan difference: creating a clean and quiet healing environment. Presented at: UHC Patient Experience

(HCAHPS) Improvement Collaborative Knowledge Transfer Web Conference; April 11, 2012. https://www.uhc.edu/docs/49016626_

UofMCreatingaCleanandQuietHealingEnvironmentApril2012.pdf. Accessed September 2012.

6

Patient Experience (HCAHPS) Improvement Collaborative 2012 Field Brief

Keeping it clean. The Michigan team initiated the Patient

Perception Program, which included environmental services

staff training, business cards, a C-L-E-A-N hotline (Figure 3),

“while you were out” reminders, and patient education about

cleaning schedules.

own television or music. For example, the Rush University

Medical Center team tested offering earplugs and eye masks to

patients and improved their “quiet at night” score by 5%.

Patient Perception P

Quietness Tips From Collaborative Participants

•

•

•

•

•

C

ollect baseline noise levels and set improvement goals.

Assess and address major sources of noise.

Interview patients to understand their noise concerns.

Partner with vendors to develop quieter work processes.

Alert patients about unusual sources of noise and the

expected duration, and then meet that expectation.

Figure 3. Card for C-L-E-A-N Phone Line at

University of Michigan Hospitals & Health Centers

Staff traini

Business c

C-L-E-A-N

“while you

Customer

Meet Cleanliness Goals by Recruiting, Training

Staff With a Customer Service Orientation

Professional, efficient staff. Environmental services staff

members are a linchpin in the patient experience and should

therefore be recruited and trained for a customer service

orientation. Collaborative teams educated environmental

services staff on the importance of hospitality and communication and frequently shared patient satisfaction data with

staff to ensure understanding and support.

Source: Rutherford R, Bear P. The Michigan difference: creating a clean and quiet

healing environment. Presented at: UHC Patient Experience (HCAHPS)

Improvement Collaborative Knowledge Transfer Web Conference; April 11, 2012.

https://www.uhc.edu/docs/49016626_UofMCreatingaCleanandQuietHealing

EnvironmentApril2012.pdf. Accessed September 2012.

Sometimes staff needed retraining to help standardize certain

procedures. Some participants found it helpful to provide the

custodial staff with a checklist and pictures to help guide how

they clean rooms after a patient is discharged. In its Picture

Perfect process, the Medical University of South Carolina team

created visual tools to help environmental services staff set up

inpatient rooms in a standardized way across the campus.

An environmental services patient representative program was

also launched, in which representatives greet newly admitted

patients, keep daily contact and follow-up logs, secure services

when needed, and recognize high-performing employees.

Managers were encouraged to shadow cleaning staff to identify gaps in service and take advantage of coaching opportunities. It was important to recognize and reward high performers for exceptional service so that behaviors became ingrained.

The Michigan team learned that environmental services staff are

accustomed to being in the background and need training and

encouragement to actively engage with patients and families.

Patient input. Participants found patient input to be invaluable in identifying and resolving cleaning issues. Leaders

interviewed patients to proactively identify concerns and

used this information to change work processes. Environmental services staff members were encouraged to work with

patients to find a mutually agreeable time for room cleaning.

Cleanliness Tips From Collaborative Participants

• M eet regularly with nursing staff to identify and address

unit-cleanliness issues.

• Include patient satisfaction goals in housekeeping evaluations (in-house and contracted services).

• R ecord, analyze, and act on cleaning audits.

• F ocus on the appearance of public areas too.

• A sk leaders from other areas to help assess cleaning quality.

• Interview staff, review patient satisfaction comments,

and change staffing and work patterns, if needed.

• E nsure that staff members have the necessary supplies

Scripts were developed for staff to explain housekeeping

activities and schedules to patients. Some teams provided a

24/7 “clean line” phone number for patients to call if problems arose or if service recovery was needed. It was important

to show physical evidence of cleaning, including leaving a

“sorry I missed you” card when the patient was absent from

the room or sleeping. Some teams selected clean-smelling

products to reinforce the cleanliness of the room.

and tools.

7

Improving Patient Experience: HCAHPS

Enhance Patient Communications

of the pain management board, confirming that it gives the

patient a sense of control and positively changes interactions

with the care team. The board helps patients and staff assess

different levels of pain and makes a useful distinction between pain and discomfort. The patient adviser commented

that the board’s structured approach is more helpful than

open-ended questions, which can be difficult for patients to

answer when they are hospitalized and feeling unwell.

Communication boards. Patient communication was

strengthened through the use of in-room whiteboards to

display important information, including names and contact

information for caregivers. The boards were updated at shift

changes and at other times as needed. Some participants

customized the boards for specific units and developed other

eye-level tools to enhance bedside education.

The UH/CMC team learned that listening to the stories of

patients and families brings their experiences into sharp relief

and helps create results-oriented solutions.

Using whiteboards to identify pain problems and solutions. The UH/CMC team piloted a new pain management

process that moved satisfaction performance from the 8th to

the 75th percentile for the pilot unit. The team’s pain management strategy incorporated a standardized pain bundle,

patient and staff education, and interdisciplinary communication between the care team and the patient. A special pain

management whiteboard was created and used in patients’

rooms as a visual representation of what interventions are

available, what has been tried, what works, and what does

not work for each patient (Figure 4).

Bedside interdisciplinary rounds. Collaborative participants encouraged care team members to gather at the bedside to discuss key issues with patients, family members, and

each other as way of keeping communication lines open.

Permission for these rounds was obtained from patients in

semiprivate rooms. If family members could not be present,

a designated point person was briefed by phone.

Physicians were asked to call ahead to notify staff about the

most efficient time to gather. To obtain buy-in for rounds,

teams emphasized the benefits: safety enhancements, fewer

delays, and fewer phone calls.

This customized technique involves the patient in his or her

own pain management decisions and facilitates the exchange

of information during staff handoffs. A patient adviser working with the UH/CMC team provided feedback on the value

Nursing change-of-shift communication at the bedside.

At many participant organizations, nurses used change-ofshift times to communicate at the bedside with each other

and their patients. Aides were asked to round and provide

comfort care during the bedside report. Some teams displayed a tabletop sign to alert others about the need for

uninterrupted time to talk. Whiteboards in the patients’

rooms were updated during the report.

Figure 4. Pain Management Plan Whiteboard at

University Hospitals Case Medical Center

Some collaborative participants offered simulation labs to

help nursing staff seamlessly transition to the new reporting

process. Nurses were reminded to ask patients in semiprivate

rooms for permission to conduct beside conversations.

Postdischarge calls. Patients were called within 48 to

72 hours of discharge by discharging nurses or other appropriate staff to assess their health condition, check compliance,

identify problems, and answer questions. Collaborative teams

won staff support for these calls by sharing patient feedback

and “saves” from negative situations, publishing rates of completed calls, and training float or light-duty staff to assist with

calls. Electronic medical records and other existing electronic

systems were adapted to capture and analyze the information

obtained during the calls.

MacDonald Women’s Hospital

Source: Vidal K, Dragon MA, Furnari R, Milter C. Improving HCAHPS 5by

increasing communication. Presented at: UHC Patient Experience (HCAHPS)

Improvement Collaborative Knowledge Transfer Web Conference; April 16, 2012.

https://www.uhc.edu/docs/49016628_UHCaseApril162012.pdf. Accessed

September 2012.

Connecting with patients at home. The Stanford Hospital & Clinics team focused on postdischarge calls because

nursing units frequently received phone calls from patients

8

Patient Experience (HCAHPS) Improvement Collaborative 2012 Field Brief

with follow-up questions but did not have a standardized

process for addressing those concerns. In addition to a positive effect on HCAHPS discharge communication scores, the

success of postdischarge phone calls is linked to lower readmission rates, higher quality outcomes, and the likelihood of

recommending the hospital.

Training and accountability. Communication training

helped collaborative participants define new standards, instill

and reinforce skills, and hold staff accountable for the patient

experience. Staff members were taught to knock first, introduce

themselves, call patients by their desired names, explain their

roles, make eye contact, smile, invite questions, and then listen.

Beginning in April 2011, calls were placed by nurses, with the

goal of contacting 100% of patients at home within 72 hours

of discharge. Making 2 attempts to contact each patient, the

callers have been able to connect with 96% of patients, compared with 59% at the program’s start (Figure 5). Stanford

has experienced substantial improvements in Press Ganey

scores related to instructions at home, moving from the 45th

to the 99th percentile since the pilot began. Nurses enjoy

hearing directly from patients and have been able to prevent

adverse events for several patients by addressing issues with

medications and follow-up appointments.

Scripts, skill labs, films, and question prompts were helpful training tools. Patients and family members were invited

by some teams to serve as faculty for training programs and

provide different perspectives. Leaders also participated in the

training sessions to demonstrate support and commitment.

To promote a permanent change in behavior, some teams

arranged for a trainer to observe and coach staff. Training

effectiveness was validated by interviewing patients and auditing

staff practices. At Vanderbilt University Medical Center, coaches

are available to observe the interactions between providers and

patients and assist in improving communication skills.

The Stanford team learned that leadership buy-in and demonstration of support for staff are crucial to success. Phone

calls must be viewed as a culture change and an extension

of patient care, not an extra duty. Patients appreciate the

personal phone calls, which provide opportunities for service

recovery when needed.

Participants worked to embed service expectations in

hiring, orientation, and evaluation processes to underscore

their importance. Teams also shared performance data and

patient comments with staff to reinforce the impact of

positive and negative behaviors.

Figure 5. Patients Contacted Within 72 Hours of Discharge From Stanford University Hospital & Clinics,

April 2011-February 2012

Percentage of Patients Contacted

120

96%

100

79%

80

60

59%

67%

46% 46%

86%

85%

72%

45%

42%

40

20

0

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct Nov

Dec

Jan

Feb

(n= 59) (n= 90) (n= 56) (n= 71) (n= 43) (n= 71) (n= 63) (n= 72) (n= 87) (n= 104) (n= 80)

Source: Adapted from Abbott K. Stanford discharge phone calls program. Presented at: UHC Patient Experience (HCAHPS) Improvement Collaborative Knowledge

Transfer Web Conference; April 16, 2012. https://www.uhc.edu/docs/49016627_StanfordDischargePhoneCalls41612pptx.pdf. Accessed September 2012.

9

Improving Patient Experience: HCAHPS

The Next Step Is Yours

Consult your organization’s customized quarterly Imperatives

for Quality Report to compare your performance with that of

your peer groups by HCAHPS domain and identify areas for

improvement and better performers.

Patient satisfaction and its related reimbursement incentives

make it an essential element of UHC’s Improving Patient

Experience imperative, which includes HCAHPS, Clinician

and Group CAHPS, and palliative and hospice care.

Collaborative participants are progressing with their improvement initiatives, moving pilots into full-scale operation, and

expanding the patient experience to encompass care beyond

the inpatient setting. UHC member networking and problem

solving continues via the Patient Satisfaction listserver. Contact

Jorie Garbacz at (312) 775-4265 or garbacz@uhc.edu if you

want to participate.

Other UHC resources on best practices and improvement

strategies include the Patient Satisfaction (HCAHPS) Benchmarking Project 2011 Field Brief, Patient Experience Tools

and Resources Web page, HCAHPS suggested best practices,

Value-Based Purchasing Web page, interactive VBP Calculator,

and Performance Improvement Tool Kit.

For More Information

To learn more, contact Kathy Vermoch, project manager, at (312) 775-4364 or

vermoch@uhc.edu.

10

Patient Experience (HCAHPS) Improvement

Collaborative Participants

Duke University Health System (Duke University Hospital)

UCSF Medical Center*

Fletcher Allen Health Care

University Hospitals Case Medical Center

Froedtert & The Medical College of Wisconsin

University of Arizona Health Network (The University of

Arizona Medical Center–University Campus)

Georgia Health Sciences Medical Center*

Greenville Hospital System (Greenville Memorial Hospital)

University of Colorado Hospital*

Hennepin County Medical Center

The University of Connecticut Health Center, John

Dempsey Hospital

Highland Hospital*

University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics

Indiana University Health

The University of Kansas Hospital Authority

Loyola University Medical Center

University of Kentucky Hospital

Medical University of South Carolina

University of Michigan Hospitals & Health Centers*

The Methodist Hospital System (The Methodist Hospital)

University of North Carolina Hospitals

The Nebraska Medical Center

University of Pennsylvania Health System

(Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania)

NYU Langone Medical Center

Oregon Health & Science University

Penn State M.S. Hershey Medical Center

Rush University Medical Center*

Shands Jacksonville Medical Center, Inc.

Stanford Hospital & Clinics

St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital

Stony Brook University Medical Center

University of Rochester Medical Center Strong

Memorial Hospital

University of Utah Hospitals and Clinics

University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics

Upstate University Hospital

Vanderbilt University Medical Center

Vidant Health (Vidant Medical Center)

SUNY Downstate Medical Center/University Hospital

Virginia Commonwealth University Health System

(MCV Hospital)

Thomas Jefferson University Hospital

Wexner Medical Center at The Ohio State University

* Had 2 teams in the collaborative

155 North Wacker Drive

Chicago, Illinois 60606

312 775 4100 main

312 775 4580 fax

uhc.edu

© 2012 UHC. All rights reserved. The reproduction or use of this document in any form or in any information storage and retrieval system is forbidden without

the express, written permission of UHC; however, participants in UHC’s Imperatives for Quality (IQ) Program may copy portions of the document for internal use

only at any time.

11/12 IQ0512