Did Women Listen to News? A Critical

advertisement

DID WOMEN LISTEN TO NEWS?

A CRITICAL EXAMINATION

OF LANDMARK RADIO AUDIENCE

RESEARCH (1935-1948)

By Stacy Spaulding

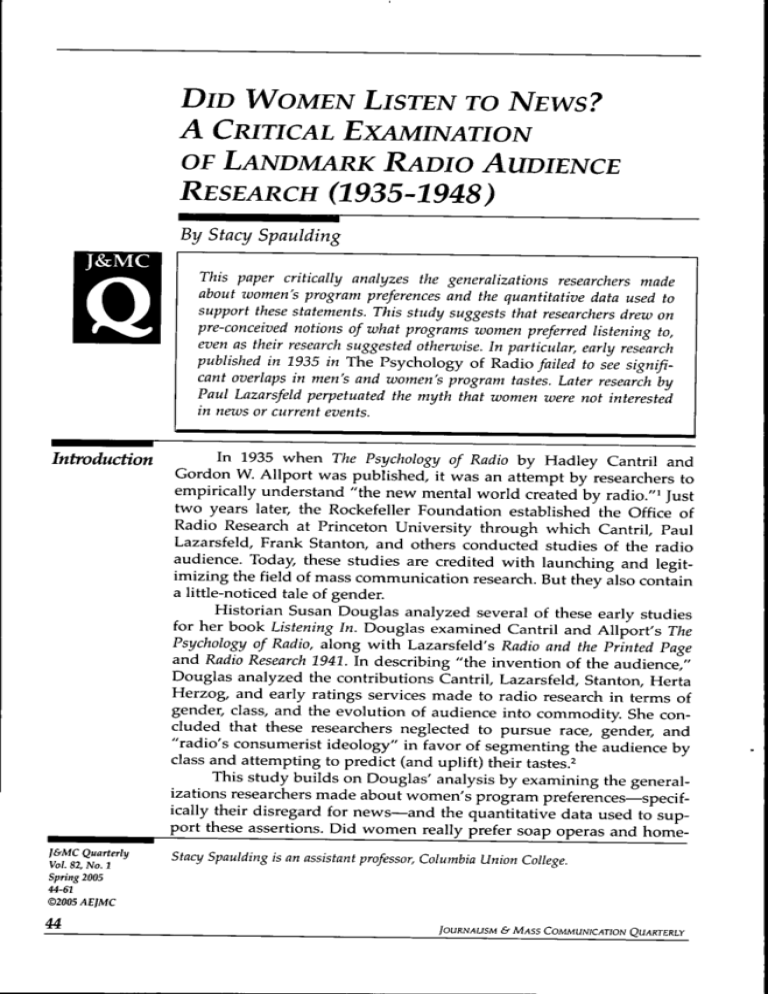

This paper critically analyzes the generalizations researchers made

about women's program preferences and the quantitative data used to

support these statements. This study suggests that researchers drew on

pre-conceived notions of what programs women preferred listening to,

even as their research suggested otherwise. In particular, early research

published in 1935 in The Psychology of Radio failed to see significant overlaps in men's and women's program tastes. Later research by

Paul Lazarsfeld perpetuated the myth that women were not interested

in news or current events.

Introduction

^ ^ ^

I&MC Quarterly

Vol. 82, No. 1

Spring 2005

44-61

©2005 AE]MC

44

I" 1935 when The Psychology of Radio by Hadley Cantril and

Gordon W. Allport was published, it was an attempt by researchers to

empirically understand "the new mental world created by radio."' Just

two years later, the Rockefeller Foundation established the Office of

Radio Research at Princeton University through which Cantril, Paul

Lazarsfeld, Frank Stanton, and others conducted studies of the radio

audience. Today, these studies are credited with launching and legitimizing the field of mass communication research. But they also contain

a little-noticed tale of gender.

Historian Susan Douglas analyzed several of these early studies

for her book Listening In. Douglas examined Cantril and AUport's The

Psychology of Radio, along with Lazarsfeld's Radio and the Printed Page

and Radio Research 1941. In describing "the invention of the audience,"

Douglas analyzed the contributions Cantril, Lazarsfeld, Stanton, Herta

Herzog, and early ratings services made to radio research in terms of

gender, class, and the evolution of audience into commodity. She concluded that these researchers neglected to pursue race, gender, and

"radio's consumerist ideology" in favor of segmenting the audience by

class and attempting to predict (and uplift) their tastes.^

This study builds on Douglas' analysis by examining the generalizations researchers made about women's program preferences—specifically their disregard for news—and the quantitative data used to support these assertions. Did women really prefer soap operas and homeStacy Spaulding is an assistant professor, Columbia Union College.

JOURNALISM & MASS COMMUNICATION QUARTERLY

making programs instead of news programs, as was commonly

believed? The evidence examined for this paper suggests that researchers failed to see the ways their own data contradicted the dominant ideology regarding women's program preferences. In particular, early

research published in 1935 in The Psychology of Radio did not report the

significant overlaps between men's and women's program tastes. Later

research by Lazarsfeld also perpetuated the myth that women were not

interested in news, though his data tables suggest otherwise.

This study is a narrative historical inquiry that values the concept

of gender as a lens through which to examine the past. It is important to

understand that this does not imply a "present-minded"^ analysis in

which the past is judged according to the cultural standards of today.

This study instead utilizes the concept of gender as a tool to uncover and

dissect the power and political relationships that shaped a particular

moment in history. Gender "seems to have been a persistent and recurrent way of enabling the signification of power," wrote historian Joan

Scott. "Gender, then, provides a way to decode meaning and to understand the complex connections among various forms of human interaction."'' Particularly when examining media history, gender allows the

researcher to uncover and examine cultural contradictions that are

often hidden within media narratives by a "façade of normalcy."^

Understanding this façade, and what it conceals, not only allows us to

understand how social power and interaction were enacted at one point

in media history, but how social power may have even shaped the narrative of media history itself.

This study first outlines the pertinent historical background by

describing early radio audience research, the gendered dichotomy of

radio programs, and the emergence and influence of Lazarsfeld and the

Bureau of Applied Social Research. An examination follows of the landmark studies in early radio research: The Psychology of Radio (1935) by

Cantril and Allport; Radio and the Printed Page (1940) by Lazarsfeld; Radio

Research 1941 by Lazarsfeld and Stanton; Radio Research 1942-43 by

Lazarsfeld and Stanton; The People Look at Radio (1946) by Lazarsfeld;

Radio Listening in America: The People Look at Radio—Again (1948) by

Lazarsfeld and Patricia L. Kendall. These studies—all but one products

of the Office of Radio Research and the Bureau of Applied Social

Research and shaped by Lazarsfeld—are important to examine. They are

credited with legitimizing mass communication research, establishing

the media effects tradition, and influencing mass media research and theory for years to come.

In 1926, when radio was still in its infancy, a letter to the

magazine Radio Broadcast sparked a debate that would last for

decades. Were women's voices suitable for radio? The answer is an

intriguing example of early audience research. The letter reported

the results of a poll of 5,000 WJZ listeners in New York that claimed

male voices were preferred nearly 100 to 1. Said WJZ manager Charles

B. Popenoe:

DID WOMEN LISTEN TO NEWS?

Historical

Background

45

It is difficult to say why the public should be so unanimous

about it. One reason may be that most receiving sets do not

reproduce perfectly the high notes. A man's voice "takes"

better. It has more volume. Then, announcers cover sporting

events, shows, concerts, operas and big public meetings.

Men are naturally better fltted for the average assignment of

the broadcast announcer.""

It is not known just how reliable the survey was. The original column in which the results were reported contains no clues as to how the

research was performed. Some historians doubt the legitimacy of the

poll. Michelle Hilmes, author of the book Radio Voices and a cultural history of broadcasting titled Only Connect, referred to the survey results as

"somewhat suspect" and said the results "would continue to be reported as fact and would act as a barrier to women in radio, except in daytime shows directed at female audiences."' Invisible Stars author Donna

Halper believes that the survey was not a reliable indicator of audience

preferences, since in the 1920s concepts of the audience and audience

research were not well deñned. Halper hypothesized that the survey

was not a scientific sample of listeners, but a collection of letters from

mostly male "active" listeners who were very vocal about what they

liked and disliked. These were the listeners most likely to write in to the

station, she wrote.*

As radio gained legitimacy, so did audience research. But the ability to cull a random or representative sample was not signiflcant to early

researchers focused on the commercial applications of the findings. "It

is assumed that the bias inherent in each method is not of great importance," wrote one researcher in 1934.' Some stations offered free items

to listeners who wrote to the station, a tactic that was likely to generate

an avalanche of letters but not a reliable sample of listeners. Telephone

interviews were also widely used, but this method was not able to capture the thousands of radio listeners who did not own telephones.

The problem of representing women's voices in audience research

wasn't the only gender issue debated by Radio Broadcast. A year earlier,

one columnist lamented the dichotomy of programs considered appropriate for women and men. Like the suitability of women's voices, this

issue would be debated for decades as programs were divided into

"male" and "female." Programs deemed to have a mostly male audience included commentary, news, and sports; women's programs

included homemaking, music, and soap operas.

Radio Broadcast columnist Kingsley Welles, in a 1925 column titled

"Do Women Know What They Want in Radio Programs?," praised a

Cambridge forum in which a graduate called for talks "of a non-domestic character" for female audience members. In a response to a call for

listeners to express their own views, 80% of the letters sided with the

graduate, Welles said. "Cookery, child welfare, and household management talks were not wanted. The general cry was: 'Take us out of the

kitchen and take us out of ourselves!' "'" As noted with the Popenoe

survey of WJZ listeners, a call for letters is by no means a reliable audi46

JOURNALISM & MASS

COMMUNICATION

QUARTERLY

ence sample. But what is notable is that in 1925 (just tive years after the

tirst radio broadcasts) some women were already speaking out against

so-called women's programs. Welles wrote:

Almost without exception American broadcast stations,

when they have a program for women, have limited it to the

obvious domestic things. No broadcaster has had the courage

or the intelligence to arrange a program to appeal to the intelligence of a woman. One wonders whether this failure is due

to a belief that it would be useless to make the attempt or

because the program designers simply fail to appreciate the

necessity."

As early as the 1920s, the female audience had been a powerful

draw for advertisers who realized that women made the majority of purchasing decisions. However, it is not known if early radio executives ever

seriously considered the power and influence of the female audience. In

the book Radio: The Fifth Estate, published in 1946 as a textbook for use

with NBC's Northwestern University Summer Radio Institute, radio pioneer Judith Carey Waller wrote that women's programs were frequently

"unwanted children—there to till the air until something better came

along."'^ They were always "a matter for perennial discussion and controversy" by male executives who considered women's preferences as

"more than slightly mysterious."'^

Radio executives did pay close attention to program ratings, however. But these ratings services—tirst the Crossleys and Hooperratings

and later the Nielsens—were commercially motivated, wrote Eileen R.

Meehan. They depended on measuring target audiences to create numbers they then sold to station managers and advertisers. The ratings

measured only the audience members that made a desirable target for

advertisers, what Meehan called the "consumerist caste." Others may

have enjoyed programs—men may have listened to soap operas, for

example, and women may have listened to sports—but these additional

audience members were "economically irrelevant" to the advertiser.''»

"Women's genres are designed to target the women in the consumerist

caste, and ratings are designed to measure only those ladies of the

house," Meehan wrote.'^ Thus, in its attempt to manufacture a saleable

audience, the economics of early radio may have legitimized the ideological divide of men's and women's programming, and even the domestic

division of labor itself."

Many early programming plans assumed women would be the primary audience. However, women were never recognized as such, wrote

Hilmes in Radio Voices." Radio at this time was flghting a batfle of definition. Was it a public institution or a commercial venture? Radio was

dependent on selling a product to an economic base of female audience

members. But broadcasters also had to convince regulators that they

existed to serve the public interest, not just sell a product. Thus, radio's

"mass/private/feminine base constantiy threatened to overwhelm its

'high'/public/masculine function."'"

DID WOMEN L;STEN TO NEWS?

This low culture/high culture division pervaded the early radio

audience research of one of the greatest figures in mass communicafion

research: Lazarsfeld. His Radio and the Printed Page, for example, sought

to discover how to "build audiences for serious broadcasts among people on lower culhiral levels.'"' This perspective had root in Lazarsfeld's

former life in Vienna, where he was a member of the Socialist

Democrafic Party of Austria, wrote Douglas. Lazarsfeld and his colleagues sought to improve condifions for the working class, hoping to

encourage them to spend less leisure fime carousing and more fime

reading, attending lectures, and listening to serious music. Lazarsfeld

fully took part in Vienna's unique mixture of culture and polifics, psychoanalysis, and Marxism, even playing the viola at regular chamber

music evenings.™

Though Vienna's socialist polifics were celebrated by intellectuals

and the working class alike, Douglas wrote that they embodied cultural

contradicfions that may have infiuenced Lazarsfeld's later research. The

pursuits advocated by Lazarsfeld and his peers in Vienna exemplified

these inherent inconsistencies in that they were "favored by the educated bourgeoisie, the very class Lazarsfeld and his comrades disdained."^'

These contradictions "crossed the Afianfic with Lazarsfeld and left their

mark on radio research and on concepfions of the radio audience,"

wrote Douglas.^^

Lazarsfeld came to the United States in 1933 as a visiting

Rockefeller Foundafion Fellow and decided to stay in 1935 to work

with the Radio Research Project at Princeton University. It was funded

by the Rockefeller Foundafion and directed by Cantril, Lazarsfeld, and

Stanton of CBS.^'' Lazarsfeld became director of the project, which

was renamed the Bureau of Applied Social Research in 1944 when

Rockefeller Foundation funding ended. Radio research confinued as

one branch within the Bureau, located at Columbia University.^'' Out

of both of these projects came a number of book-length studies on radio authored by Lazarsfeld and co-authored by a variety of other

researchers.

Lazarsfeld is revered for transforming sociological research methods and establishing mass communicafion research as a legitimate field

for academic research. "No one has had a greater influence in shaping

the current state of organized social research and training," wrote

Charles Y. Glock, a coder for Lazarsfeld from 1941 to 1942.^5 Lazarsfeld's

greatest contribufions, according to Glock, were his development of a

university-affiliated social science research organizafion, his pioneering

methodological advancements, his combined use of quanfitafive and

qualitafive methods, and his "clear formulafion of research problems."^^

Books on the history of mass communicafion research offer an

indicafion of the stature Lazarsfeld has been accorded in the field.

Wilbur Schramm called Lazarsfeld one of the "founding fathers" of

communication research.^' Everett M. Rogers credited Lazarsfeld with

"launching" mass communication study in media effects.^' Shearon A.

Lowery and Melvin L. DeFleur praised Lazarsfeld not only for inifiafing

the academic study of mass media, but also for legifimizing the study of

48

JOURNALISM & MASS COMMUNICATION QUARTERLY

"low culture" through research such as Herzog's qualitative study of

soap opera listeners.^'

These media histories also critique Lazarsfeld's contributions to the

field, such as his dependence on corporate grants to fund research.

Lazarsfeld had a background in market research and frequent contact

with successful businessmen who funded his research.^ He was wellknown for paying the debt from his last study with the grant from the

next and using corporate grants to fund his academic studies, a technique he termed "Robin Hooding."^' Lazarsfeld often did research for

CBS, NBC, and several advertising agencies, using the proceeds to pay

for his academic studies. '^ As a result of his dependence on funding, his

"correlations were a litfle too pat,"'' and he may have failed to explore

the data fully, Douglas wrote.

Lazarsfeld has been criticized for neglecting issues of ownership,

control, and state regulation of broadcasting as an industry.'^ In addition

to failing to critique the bureaucratic structures of the media, Lazarsfeld's

empirical work generated scores of statistics and data, but few real observations on human behavior.'^ Also troublesome is the elitist conception

of the audience in much of the work supervised by Lazarsfeld. Though

some scholars call Lazarsfeld's work "mildly elitist and sexist,"'*^

others are more direct in their censure. Douglas wrote that Lazarsfeld's

"ambivalence about the audience—uncultured, anti-intellectual knownothings who nonetheless deserved on-air cultural missionary work—

... legitimized a patronizing stance toward media audiences."^'

Missing from these ethical, empirical, and elitist concerns is a gender-based critique of this era of research. The absence of such a critique

was noticed in 1981 when scholar Helen Baer wrote that "a comprehensive feminist critique of the sexist orientation and assumptions of this

school of mainstream media sociology has yet to be written."'* The

beginnings of such a critique are evident in the work of contemporary

scholars. As noted earlier, Douglas wrote that early radio research

ignored women listeners in favor of "promoting a dominant, consumerist ideology."'^ And in her analysis of the political economy surrounding ratings services, Eileen R. Meehan has noted that the tendency

of early radio to promote consumerism was reinforced by the eagerness

of commercial ratings services to create audiences to sell to advertisers.""

But questions still remain about this era of mass communication

research that can be addressed by a gender-based critique. To what extent

did this research promote a particular view of women radio listeners for

commercial customers? What role did this research play in either promottng or questioning the dominant gender ideologies of the day? Just

as a feminist critique of media content analyzes how discourses of gender are encoded in media texts,"' a gender critique of this era of research

can draw on a similar focus. How are discourses of gender encoded in

media research? What meanings of gender are available in these texts?

How have these meanings influenced media content and society?

A gender critique can generate more knowledge about the way this

era of research institutionalized and privileged certain academic research

methods. Such a critique asks how social and cultural views of a particDiD WOMEN LISTEN TO

NEWS?

49

ular era creep into research, preserved by supposedly impartial statistics, and reinforce a particular view of history that may or may not be

correct. This allows researchers to critically examine not only the factual history of mass communication research, but even how the narrative

fabric of that history is constructed.

One of the first tasks in creating such a critique of mass communication research is to focus on the gender assumptions implicit in its

major works. This paper attempts to question one such gender assumption by asking whether women actually listened to news or not.

The

Psychologu

ofRadio

•'

Lazarsfeld called the Psychology of Radio "the tirst great book on

radio.""^ Published in 1935, Cantril and AUport's volume of experimen'^^ findings represented an important landmark in the beginning of

radio research. The authors regarded radio as a "signiticant social problem" for psychologists because of its feared potential for social control."^'

They hoped their data could ultimately help legislators determine how

best to control radio for social good.""

The picture of women listeners that emerges from this book is contradictory. The authors call attention to discrimination against women

announcers, but selectively analyze women's program preferences. To

assess program preferences, the authors surveyed 1,075 men and

women, asking them to rank 42 programs from most preferred to least

preferred (see Table 1). An initial analysis using Spearman's rho shows

there are correlations between men's and women's program preferences,

yielding a rho of .497 (p<0.01, two-tailed). Similar correlations also

occurred when examining program preferences for men and women

under 30 {r^= .548, p<0.01, two-tailed) and for men and women over 30

(r, = .515, p<0.01, two-tailed).

An analysis of the table for all men and women, when compared

with the accompanying narrative, is most revealing. The narrative

reports that all listeners, both men and women, enjoyed news reports,

various musical programs, drama, humor programs, and educational

talks."' But the authors also note that men and women have different

tastes. The researchers write that women enjoy symphonies, operas,

dance orchestras, short stories, literature, organ music, vocal artists, new

jazz songs, dance music, classical music, poetry, educational talks,

church music, sermons, and "of course, fashion reports and recipes."

Meanwhile, men are said to enjoy sports, business news, national policy

talks, detective stories, and talks on engineering, physics, or chemistry.

"Men even prefer advertisements to fashion reports," they write."*Though the study's narrative gives the impression that men's and

women's tastes are widely varied, a closer look at the data reported in

the table gives a different picture. In actuality, men's and women's tastes

may have overlapped a great deal, a reasonable finding in an era when

families typically owned only one radio and shared listening time. Five

types of programs rank among the top ten preferred programs for all

men and women: symphonies, old song favorites, dance orchestras,

news, and humorists. Men's and women's tastes are so similar, in fact,

that nearly half of all programs on the list are ranked within tive spots

^ "

JOURNALISM & MASS

COMMUNICATION

QUARTERLY

TABLE 1

Men's and Women's Rank Order of Radio Program Preferences

This is a compilation of men's and women's ranked order of radio programs, taken from The

Psychology of Radio, 1935. Table XII and XIII, pp. 91-92. The authors of the study used brackets to

indicate that a particular set of programs were tied for a ranked spot. A minus sign was used to

indicate a negative score, indicating listeners actually wanted to hear less of a particular program.

Rank

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

17

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

Total men

Football

Sports

Old song favorites 1

Boxing

J

News events

Baseball

Humorists

Dance Orchestras

Hockey

Symphonies

Drama

Educational talks

National policies "1

Psychology

r

Short stories

J

Health

T

Famous people J

Detective stories

History

Engineering

Vocal artists

"I

Physics or chemistry \

Tennis

J

Dance music

Operas

Literature

Educational methods

Organ music

Classical music

New jazz songs

Astronomy

Jazz singers

Church music

I

Phonograph records!

-Poetry

1

-Foreign language instruction J

-Political speeches

-Business and stock reports

-Sermons

-Recipes and cooking

-Advertisements

-Fashion reports

D I D WOMEN LISTEN TO

NEWS?

Total women

Symphonies

Old song favorites

Dance orchestras

Drama

Opéras

News events

Short stories

Humorists

Literature

Organ music

Educational talks

Psychology

Vocal artists

Health talks

New jazz songs

Famous people

Educational methods

History

National policies

Dance music

Classical music

Football

Fashion reports

Poetry

Sports

Detective stories

Church music

Recipes and cooking

Baseball

Jazz singers

Tennis

Boxing

\j

Astronomy

Sermons

Hockey

Foreign language instruction

-Phonograph records

-Physics or chemistry

-Poiitical speeches

-Engineering

-Business and stock reports

—Advertisements

51

of each other. The main difference between men's and women's preferences is not the prevalence of so-called women's programs, but men's

enthusiasm for sports. Half of men's top ten ranked programs were

sports-oriented, including football, boxing, baseball, and hockey.

In fact, of the programs the authors highlighted as "women's

favorites," only three were in women's top-ten ranked list. Most were

much lower on the list. Out of a total of 42 programs, dance music

ranked 20th, classical music ranked 21st, poetry ranked 24th, church

music ranked 27th, and sermons ranked 34th. Most surprisingly, some

programs thought to be highly favored by women ranked in die lower

half of the list: fashion reports ranked 23rd and recipes ranked 28th.

Perhaps most revealing in the narrative analysis is the authors' statement that women prefer listening to recipes and sermons. However, in

the table both programs are bracketed, indicating that they were tied

with other programs in the ranked list. In this case, recipes tied with

baseball and sermon programs tied with hockey. Though it sounds natural to say that women preferred sermons and recipes, the authors could

also have said women preferred listening to baseball and hockey.

Likewise, the authors claim that men prefer business news. This

type of program, however, is ranked 38th on men's list. Women ranked

it similarly at 41. Also, in both cases on the data table the program has a

minus sign in front of it, indicating the program had a cumulative negative score and that men and women actually wanted to hear less of this

type of program.

Germane to the topic of this paper, it must be noted that both men

and women report that they enjoy listening to news. The data show that

men ranked news as 5th and women ranked it 6th. Though the researchers

note that news ranked high with all listeners, they do not take special note

of women's high rankmg of news programs. This picture conti-adicts the

authors' expressed hopes of what radio could do for women. Early in the

book, they hope that "the housewife may tind the loud-speaker more

entertaining than the back fence as her mind becomes occupied with

affairs of the outside world rather than with those of her neighbors."*'

Other data in the book also reflect women's strong interest in news and

the effect radio had in increasing that interest. Of the women who

answered Cantril and Allport's research questionnaire, 72% reported

that they preferred listening to news events on the radio to reading about

them in the newspaper. And 91% reported that they preferred listening to

a speech on the radio rather than reading it in the newspaper.*^ Despite

their hopes that radio would cause housewives to be more concerned with

national and world affairs, the researchers did not make special note of a

clear statement from women that they enjoyed and even preferred radio

news to other programs and other media of news delivery.

Lazarsfeld

and Radio

Audience

Research

52

In 1940, flve years after the publication of The Psychology of Radio,

Lazarsfeld's flrst book-length work on radio was published. Radio and

the Printed Page represented a different approach to the study of radio.

While the research published in The Psychology of Radio was primarily

experimental. Radio and the Printed Page was a sociographic analysis of

JOURNALISM & MASS COMMUNICATION QUARTERLY

radio listeners. This shift was in part due to the influence of early rafings

services, according to oral histories of Lazarsfeld.

...I had never done experiments and it was only chemists

who do that, so what I wanted to do of course is go on

with the art of asking why ... And then I learned about

ratings, you see, the networks had always collected ratings,

and then I said, well, why don't we turn around ... find out

who listens to what in terms of age, sex and education, you

see?«

Lazarsfeld stated that he was an eligible candidate for the

Rockefeller Foundation's radio project because he had done radio

research for the Austrian government, but that he didn't see a difference

between radio research and other types of market research: "...there was

little difference between chocolate research and radio research."5° The

topic of radio never really interested him. Lazarsfeld found radio to be

"an undignified and trivial topic."'' He was never even sure if he was

ever genuinely interested in mass communication research:

You see, what became the earmark of early communicafions

research, which is this careful sociographic analysis of the

audience, you see, for which people still identify me, was an

unwilling compromise. I wanted to go on with the art of asking why, you see? But I knew enough how to handle that,

you see, and then I turned it into methodology and the whole

idea of survey analysis and the elaboration formula, and this

stuff. Then, I turned it around to something tolerable.^^

The radio studies supervised by Lazarsfeld confirmed that women

did make up a significant segment of the audience. Research published

in 1940 found that in rural areas, women spent more fime listening to

radio than men.^'^ This finding was also true in 1946 of women generally.^ In a 1941 survey of 93 women, three-quarters remembered at least

one instance in which they had been influenced by radio in their purchasing decisions. Of these women, more than half said they tried a new

product because they wanted to support a radio program.^'

Research published in Radio Listening in America showed that

women—always considered daytime listeners—did not turn off the

radio when prime-time programs and so-called men's programs came

on in the evening: "We can summarize our findings this way: A radio fan

in the morning is one in the afternoon and evening as well. Because of

their psychological characteristics, their fime schedules, and their lack of

competing interests, women who are heavy listeners at one period of the

day will tend to be radio fans throughout the day."'^

Gender, however, was not a consistent focus in any of this research.

The most consistent focus was on class and education. In Radio and the

Printed Page, Lazarsfeld stated that "programs which can be called 'lowbrow' are mainly favored by people on lower cultural levels,"^' and that

DID WOMEN LISTEN TO NEWS?

53

TABLE 2

Evening Program Preferences According to Sex and Amount

of Evening Listening

Taken from Radio Listening in America, 1948. Appendix C, Table 15, p. 137

Programs preferred by women

Less than 1 hour

Men

Women

Quiz and audience participation

Complete dramas

Semiclassical music

25

23

40%

28

27

56%

43

31

62%

53

37

65%

58

35

71%

64

42

70

43

46

40

22

55

32

23

10

19

81

68

52

52

31

74

62

42

16

24

87

73

57

59

32

78

72

44

30

25

yjjo

Men

2-3 hours

Women

3 or more hours

Women

Men

Programs preferred by men

News broadcasts

Comedy programs

Discussions of public issues

Sports programs

Hillbilly and western music

these programs "which are definitely preferred by people lower in the

cultural scale, are those which can be characterized as of deflnitely bad

taste."'^ The book advocated the concept of "audience building," or

intentionally creating conditions that facilitate an audience member's

acceptance of a "serious" broadcast.^' Admittedly, this concept has "ulterior social motives," wrote Lazarsfeld. It was tied to helping radio listeners read more books, listen to more "serious" music, and in general raise

the cultural level of the audience.™

Data that showed women did enjoy serious programming was

abundant in Lazarsfeld's Radio Listening in America: The People Look at

Radio—Again published in 1948. But this book, more than any other,

offers an inconsistent picture of female audience members. The study's

conclusions are contradicted by its own data tables. For example, in the

book's flrst chapter the authors note that the radio audience had no outstanding characteristics, except for one: "During the day most men are

at work, and the large majority of married women are at home. Women,

then, can more easily listen to the radio during the day, and they usually do. Because of this, one might modify the previous statements by saying that a sex difference is the outstanding characteristic of the radio

audience."^'

On flrst reading, this flnding seems to support the dichotomy of

men's and women's programs. Women listened during the day, when

women's programs were on. But, Lazarsfeld's comments indicate that

women listened to daytime radio out of convenience, not because of any

special distinctions of so-called women's programming. Lazarsfeld

wrote that the sex of the audience differs at certain times only because

of "time schedules of men and women," not because of "any inherent

appeals or characteristics of the medium."" He also wrote that

there was "no sex difference in demand for serious programs,"'^' and a

data summary even showed that in the daytime and evening hours

54

JOURNALISM & MASS

COMMUNICATION

QUAKTERLY

TABLE 3

The Constancy of Program Preferences

(1947 compared with 1945)

Taken from Radio Listening in America, 1948. Table 13, p. 21

Daytime Preferences: Daytime Preferences: Evening Preferences:

Men

Women

Both Sexes

1945

1947

1945

1947

1945

1947

News broadcasts

65%

n/a

Comedy programs

15

Popular and dance music

Talks or discussions about public issues 22

12

Classical music

19

Religious broadcasts

7

Serial dramas

13

Farm talks

5

Homemaking programs

14

Livestock/grain reports

61%

n/a

23

19

11

22

6

16

5

17

76%

n/a

35

21

23

35

37

12

44

6

71%

n/a

39

22

20

41

33

13

48

10

76%

54

42

40

32

20

n/a

n/a

n/a

n/a

74%

59

49

44

30

21

n/a

n/a

n/a

n/a

women overwhelmingly preferred news to other types of programs."

Nevertheless, he also claimed: "The average American woman, just like

American youth, is not interested in current affairs. This fact has been

discovered in so many areas of behavior that we are not surprised to find

it reflected also in program preferences. And it is indeed reflected, for

twice as many men like discussions of public issues and considerably

more men are interested in evening news broadcasts."^^

But this generalization does not represent the study's data (see

Table 2). The assertion that men listened to more news than women was

true only for audience members who spent less than one hour listening

to the radio in the evening. The more radio women listened to, the higher they ranked news and public discussions. And though news broadcasts are listed under "programs preferred by men," a careful reading of

the statistics in the table shows that news broadcasts were the most popular type of program for all groups of women. This finding is unchanged

from the original survey, published in 1946. Both men and women

reported that they listened to news more often than any other program

during both daytime and evening hours.'''*

These data do not show that men preferred news while women

were not interested in current affairs. The cause for this contradiction is

not apparent in the study. But a second table of data in the same study

confirms that women also preferred daytime news broadcasts over

broadcasts of soap operas and recipes. These data (see Table 3) show that

during the daytime, women listened to news and public issues programming at either the same or greater rates than men. The data show that a

greater percentage of women preferred news over homemaking programs and soap operas. This table also shows that these preferences

remained more or less constant between the 1947 and 1945 surveys that

were the basis for Lazarsfeld's Radio Listening in America and The People

Look at Radio.

DID WOMEN LISTEN TO NEWS?

55

It is also in\portant to note here that considerably more women

preferred news broadcasts to homemaking programs, and that these

numbers showed relatively little change between 1945 and 1947. This

preference is distinct: 71% of women surveyed reported preferences for

news broadcasts in 1947 compared to 48% who reported liking homemaking programs, a difference of 23%. This table shows that even fewer

women reported preferences for daytime soap operas or "serial dramas"—only 33%.

Discussion

56

Though early radio researchers generally believed that women

were not interested in current affairs, this examination of early radio

studies shows that women consistently ranked news programs among

their favorites. As early as 1935, The Psychology of Radio helped to perpetuate false assumptions regarding women's tastes by failing to recognize

that the majority of men's and women's favorite programs overlapped.

This study's analysis showed that the principal gender difference in program tastes was not women's interest in soaps, recipes, and fashion, but

men's interests in sports. This helped to perpetuate a dominant—and

apparently false—dichotomy between men's and women's program

preferences that did not reflect social conditions. After all, an overlap in

program tastes seems probable during an era when most families

owned only one radio.

Even when women listened to the radio alone in the home—during the daytime hours—research by Lazarsfeld showed that women preferred news over soap operas and homemaking shows. Yet the narrative

accompanying Lazarsfeld's research perpetuated the myth that women

were not interested in news or current affairs, again reinforcing a false

gender dichotomy.

The idea that women did prefer news is a reasonable conclusion

since these early studies were conducted during the World War II era

when news programming increased dramatically. During the war the

networks aired about twenty foreign broadcasts a day.^^ In 1940, 12.3%

of the networks' evening hours was devoted to commentators, talks,

and news, and by 1945, news and commentary filled 19.3% of the

evening schedules.*" It seems unlikely that women did not listen to

news in such an environment—indeed, it seems more probable that

women could not escape listening to news.

In their eagerness to develop research methods to apply to the

new medium of radio, and their desire to uplift audience tastes, early

mass communication researchers failed to prevent preconceived notions

of women's program preferences from contaminating their analysis.

What is striking is the inconsistency of the narrative data analysis with

the overall aims of the research. If the purpose of these studies was to

discover a way to elevate audience tastes, and if women were blamed

for not having "serious" tastes, why not study women's preferences in

some depth?

In truth, women were frequently studied, but only in their capacity as listeners to daily soap operas. The People Look at Radio claims that

JOURNALISM & MASS COMMUNICATION QUARTERLY

"listeners to daytime serials are the most thoroughly studied and best

known sector of the radio audience."" There may be two reasons for this.

First was the Rockefeller Foundation's eagerness to improve radio programs. The foundation created the Oftice of Radio Research, after all,

with the explicit intent of uplifting radio programming after John D.

Rockefeller Jr. one day wondered if something might be done to improve

the quality of radio programs.™ Daytime serial dramas were often perceived as tasteless and women were the target audience of these programs. Thus, early radio research funded by the foundation may have

focused on women radio listeners solely in their capacity as soap opera

listeners.

Second, and perhaps more important, data on daytime serial listeners was intensely interesting to advertisers who were willing to pay for

such research. A daytime serial could cost as much as $600,000 to $1 million a year in 1940, according to Variety, which represented 75% to 100%

of the advertising budget for most products." Thus, detailed marketing

information on the preferences of serial listeners, and whether advertisements were reaching them, would have been valuable. Commercial contracts with serial drama sponsors were important to Lazarsfeld's

research both during his time at the ORR and at the Bureau. He estimated that from 1946 to 1948 as much as 80% of the Bureau's budget

came from commercial contracts, which were especially important as

Rockefeller Foundation funding eroded.''^ The availability of data on

women as soap opera listeners, and the willingness of daytime programming sponsors advertisers to pay for it, may have caused researchers to

fail to pursue women's interest in other programs—programs that

researchers may have considered more "serious" but for which there was

no available funding to investigate. This is borne out by archival evidence which shows that Herzog, known for her landmark qualitative

study of women soap opera listeners, "On Borrowed Experience," published in Radio Research 1942-43, met with marketing managers regarding

her data.'^ She was also in charge of a study prepared specifically for

advertisers by the ORR titled, "Daytime Serials: Their Audience and

Their Effect on Buying."^"

Other factors may also help to explain the neglect of women's program preferences. The Bureau, through which most of the studies analyzed here were conducted, was encumbered by its affiliation with

Columbia University, in that it was created as a vehicle for training sociology students in empirical methods.^^ Lazarsfeld stated: "... you

shouldn't believe it's a radio research office or anything of the kind.

Fortunately, we had $35,000 a year from the Rockefeller Foundation to

study radio. But for one thing, the Rockefeller Foundation took it too

seriously. You see, they were aware that I used this money partly to develop a program..."""

It is also important to note that Lazarsfeld's interest was not in

radio or mass communication research, but in methodology. Radio, for

Lazarsfeld, was a vehicle for developing empirical methods. In oral history testimony, he stated, "methodology is whatever I am writing about,

you see.""

DID WOMEN LISTEN TO NEWS?

57

Thus, Lazarsfeld developed methods to answer questions posed

by those with money, whether it was the Rockefeller Foundation, NBG,

or Kolynos tooth powder. Such a climate breeds a focus on generating

data, but not necessarily pursuing the cultural contradictions inherent in

the results. And these contradictions—the idea that women were not

interested Ln news—promoted a false image of the female audience that

clearly conflicts with the researchers' own data. This image has helped

to perpetuate a dominant ideology regarding women as mass media

consumers that demands a second look by researchers. Such an analysis

holds the potential to help researchers understand the ways gender ideology has shaped social experience and social power. It may also help

researchers understand the forces that influenced the birth of media

research and which may still influence the field today.

NOTES

1. Hadley Cantril and Gordon W. Allport, The Psychology of Radio

(New York: Harper, 1935), vii.

2. Susan J. Douglas, Listening In: Radio and the American Imagination

(New York: Times Books Random House, 1999), 148.

3. James D. Startt and Wm. David Sloan, Historical Methods in Mass

Communication (Northport, AL: Vision Press, 2003), 53-54.

4. Joan Wallach Scott, Gender and the Politics of History (New York:

Golumbia University Press, 1988), 45-46.

5. Michèle Hilmes, Radio Voices: American Broadcasting, 1922-1952

(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), 289.

6. John Wallace, "Men Vs. Women Announcers," Radio Broadcast,

November 1926, 44-45.

7. Michèle Hilmes, Only Connect: A Cultural History of Broadcasting in

the United States (Belmont: Wadsworth, 2002), 48.

8. Donna Halper, Invisible Stars: A Social History of Women in

American Broadcasting (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2001), 42.

9. Frederick H. Lumley, "Synopsis of Methods," in Measurement in

Radio (Columbus: The Ohio State University, 1934), 227-32. Reprinted in

Lawrence W. Lichty and Malachi C. Topping, American Broadcasting: A

Source Book on the History of Radio and Television (New York: Hastings

House, 1975), 479-83.

10. Kingsley Welles, "Do Women Know What They Want in Radio

Programs?" Radio Broadcast, November 1925.

11. Welles, "Do Women Know What They Want in Radio Programs?"

12. Judith Carey Waller, Radio: The Fifth Estate (Boston: Houghton

Mifflin, 1946), 142.

13. Waller, Radio: The Fifth Estate, 141.

14. Eileen R. Meehan, "Heads of Household and Ladies of the House:

Gender, Genre, and Broadcast Ratings, 1929-1990," in Ruthless Criticism:

New Perspectives in U.S. Communication History, ed. William S. Solomon

and Robert W. McChesney (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press,

1993), 210.

5a

JOURNALISM & MASS COMMUNICATION QUARTERLY

15. Meehan, "Heads of Household and Ladies of the House: Gender,

Genre, and Broadcast Ratings, 1929-1990," 210.

16. Meehan, "Heads of Household and Ladies of the House: Gender,

Genre, and Broadcast Ratings, 1929-1990," 209,13.

17. Hilmes, Radio Voices, 147.

18. Hilmes, Radio Voices, 153.

19. Paul F. Lazarsfeld, Radio and the Printed Page (New York: Duell,

Sloan and Pearce, 1940), xiv

20. Hans Zeisel, "The Vienna Years," in Qualitative and Quantitative

Social Research: Papers in Honor of Paul P. Lazarsfeld, ed. Robert K. Merton,

James S. Goleman, and Peter H. Rossi (New York: The Free Press, 1979),

10,12.

21. Douglas, Listening In, 127.

22. Douglas, Listening In, 128.

23. Everett M. Rogers, A History of Communication Study (New York:

The Free Press, 1994), 256.

24. Rogers, A History of Communication Study, 291.

25. Charles Y Glock, "Organizational Innovation for Social Science

Research and Training," in Qualitative and Quantitative Social Research:

Papers in Honor of Paul F. Lazarsfeld, ed. Robert K. Merton, James S.

Coleman, and Peter H. Rossi (New York: The Free Press, 1979), 33.

26. Glock, "Organizational Innovation for Social Science Research and

Training," 26-28, 33.

27. Wilbur Schramm, "Communication Research in the United

States," in The Science of Human Communication: New Directions and New

Findings in Communication Research, ed. Wilbur Schramm (New York:

Basic Books, 1963), 2.

28. Rogers, A History of Communication Study, 246.

29. Shearon A. Lowery and Melvin L. DeFleur, Milestones in Mass

Communication Research: Media Effects, 3d ed. (White Plains, N.: Longman,

1995), 94-96.

30. Everett M. Rogers, "On Early Mass Communication Study,"

Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 36 (4,1992).

31. Rogers, A History of Communication Study, 294.

32. Douglas, Listening In, 139.

33. Douglas, Listening In, 143.

34. Rogers, "On Early Mass Communication Study"; Todd Gitlin,

"Media Sociology: The Dominant Paradigm," Theory and Society (6,1978):

206.

35. C. Wright Mills, quoted in Rogers, A History of Communication

Study, 311.

36. Peter Simonson and Gabriel Weimann, "Critical Research at

Columbia," in Canonic Texts in Media Research: Are There Any? Should

There Be? How About These? ed. Elihu Katz, John Durham Peters, Tamar

Liebes, and Avril Orloff (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2003), 24.

37. Douglas, Listening In, 148-49.

38. Helen Baehr, "The Impact of Feminism on Media Studies—Just

Another Commercial Break?" in Men's Studies Modified: The Impact of

Feminism on the Academic Disciplines, ed. Dale Spender (Oxford:

DID WOMEN L/STEW TO NEWS?

59

Pergamon Press, 1981), 144.

39. Douglas, Listening In, 148,

40. Meehan, "Heads of Household and Ladies of the House: Gender,

Genre, and Broadcast Ratings, 1929-1990,"

41. Liesbet van Zoonen, Feminist Media Studies (London: Sage, 1994),

42.

42. "Professor Paul F. Lazarsfeld Oral Memoir" (The New York

Public Library-American Jewish Committee Oral History Collection,

Dorot Jewish Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and

Tilden Foundations, 1975), 65.

43. Cantril and Allport, The Psychology of Radio, vii.

44. Cantril and Allport, The Psychology of Radio, viii.

45. Cantril and Allport, The Psychology of Radio, 92, 93.

46. Cantril and Allport, The Psychology of Radio, 94.

47. Cantril and Allport, The Psychology of Radio, 24.

48. Cantril and Allport, The Psychology of Radio, 99.

49. "Professor Paul F. Lazarsfeld Oral Memoir," 66.

50. "Professor Paul F. Lazarsfeld Oral Memoir," 65.

51. "Professor Paul F. Lazarsfeld Oral Memoir," 68.

52. "Professor Paul F. Lazarsfeld Oral Memoir," 69, 70.

53. Lazarsfeld, Radio and the Printed Page, 225.

54. Bureau of Applied Social Research Columbia University, The

People Look at Radio (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press,

1946), 97, 98.

55. Paul F. Lazarsfeld and Frank N. Stanton, Radio Research (New

York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1941), 270-72.

56. Paul F. Lazarsfeld and Patricia L. Kendall, Radio Listening in

America (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1948), 16.

57. Lazarsfeld, Radio and the Printed Page, 21.

58. Lazarsfeld, Radio and the Printed Page, 23.

59. Lazarsfeld, Radio and the Printed Page, 118-28.

60. Lazarsfeld, Radio and the Printed Page, 128-32.

61. Lazarsfeld and Kendall, Radio Listening in America, 14.

62. Lazarsfeld and Kendall, Radio Listening in America, 14.

63. Lazarsfeld and Kendall, Radio Listening in America, 40-41.

64. Lazarsfeld and Kendall, Radio Listening in America, 21, table 13.

This table reproduced here as Table 3.

65. Lazarsfeld and Kendall, Radio Listening in America, 27.

66. Columbia University, The People Look at Radio, 103, 33, 35, 38-39.

67. Erik Barnouw, The Golden Web, vol. 2 (New York: Oxford

University Press, 1968), 140.

68. Radio Broadcasting Yearbook, 1940-1947.

69. Columbia University, The People Look at Radio, 50.

70. Rogers, A History of Communication Study, 267.

71. Hubbell Robinson, Jr. "How Daytime Radio Got That Way," in

Variety, 26 June 1940, 41.

72. "Professor Paul F. Lazarsfeld Oral Memoir," 84.

73. Robert F. Elder, letter from Robert F. Elder, marketing manager of

Lever Brothers, to Herta Herzog, 8 February 1940.

oO

JOURNALISM & MASS COMMUNICATION QUARTERLY

74. Herta Herzog, "Daytime Serials: Their Audience and Their Effect

on Buying," in Bureau of Applied Social Research project files. Box 3, Folder

"B-0130-1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 BSH-commercial studies" (Columbia University

rare book and manuscript library).

75. "The Reminiscences of Paul Felix Lazarsfeld," August 1962,

Columbia University Oral History Research Office Collection, 88.

76. "The Reminiscences of Paul Felix Lazarsfeld," 92-93.

77. "The Reminiscences of Paul Felix Lazarsfeld," 148.

DID WOMEN LISTEN TO NEWS?

61

Copyright of Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly is the property of Association for Education in

Journalism & Mass Communication and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a

listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or

email articles for individual use.