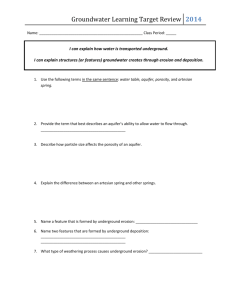

The Underground Economy

advertisement