White Opposition

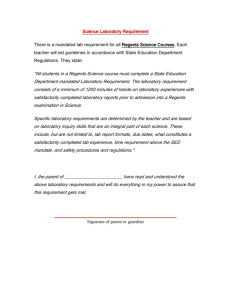

advertisement