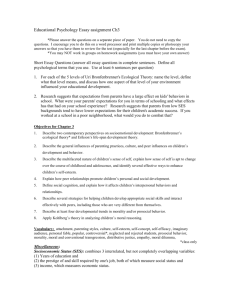

Chapter 3: Personal-Social Development: The Feeling Child

advertisement