Chapter 3: Early Learning - Health Connections

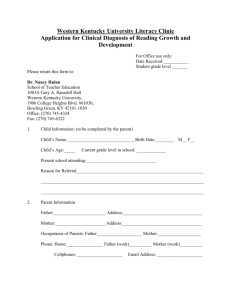

advertisement