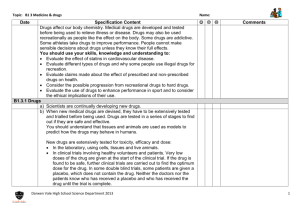

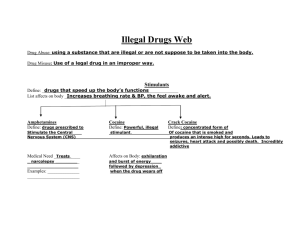

Research into knowledge and attitudes to illegal drugs

advertisement