Tax Covenants - Chapter 3 - Deferred Taxation

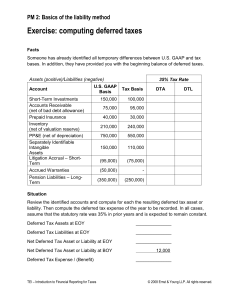

advertisement

TAX COVENANTS A PRACTICAL GUIDE A Scrutton Bland Guide Deferred Taxation 3 CHAPTER THREE DEFERRED TAXATION - WHAT IS IT? Executive Summary A The aim of deferred taxation is to ensure a consistent rate of tax on the profits of an entity, regardless of the timing of various tax adjustments. The deferred tax provision was called, very many years ago, the tax equalisation account, and this provides an insight into its function. B Deferred tax accounting involved some very subjective judgements for a period up to 2000. For this reason it has been viewed with some considerable suspicion by those without an intimate knowledge of its inner workings. Since 2000 Financial Reporting Standard 19 (“FRS 19”) (the relevant standard under UK GAAP) has required a far less subjective approach. C The relevant standard under international financial reporting standards or IFRS is IAS 12. This has a slightly different approach to deferred tax accounting but the fundamentals are the same in the two systems: neither involve subjectivity in any material way. D As subjectivity has now been largely stripped from accounting for deferred tax it is a subject that can be embraced by the non-Accountant with rather greater confidence than previously. 27 TAX COVENANTS A PRACTICAL GUIDE A Scrutton Bland Guide Deferred Taxation 3 1 Introduction 1.1 One of the themes of this book is to reach for an example when trying to explain a relevant concept. This is what we are doing in order to explain the reason for deferred tax. In chapter 2 we gave the simple example of Rickinghall Printers Limited which bought a piece of equipment for £10,000 and depreciated it over ten years. The depreciation charge was therefore £1,000 a year. The capital allowances in the first four years were £2,000, £1,600, £1,280 and £1,024 respectively. In year 8 the capital allowances were £419. If the Company made a steady profit of £2,000 a year, assuming a constant corporation tax rate of 20%, we can see the differences in the tax charges over the first 4 years. This is on the assumption that the depreciation and capital allowances on this equipment were the only adjusting items on the tax computations. We are also showing the result for year 8 in order to illustrate the trend: Year 1 2 3 4 8 £ £ £ £ £ 2,000 2,000 2,000 2,000 2,000 Add: Depreciation Less: Capital allowances Taxable profits 1,000 (2,000) 1,000 1,000 (1,600) 1,400 1,000 (1,280) 1,720 1,000 (1,024) 1,976 1,000 __(419) 2,581 Tax payable at 20% Profit after tax __200 1,800 __280 1,720 __344 1,656 __395 1,605 __516 1,484 Effective rate of tax 10.0% 14.0% 17.2% 19.75% 25.8% Profits 1.2 In this example it can be seen that the tax charged on the same level of profits virtually doubles between years 1 and 4, as the capital allowances reduce. This trend then continues as is shown in year 8. The fact that the capital allowances are available rather more quickly than the equipment is depreciated has the effect of moving the tax payments towards the final five years, rather than the first five years of the life of the equipment. 1.3 Deferred taxation works in such a way that the tax benefit which has been gained in the first 4 years is deferred (for accounting purposes only), and is then used to reduce the higher tax charge that arises in the later years. It has no impact on cash flows. 28 TAX COVENANTS A PRACTICAL GUIDE A Scrutton Bland Guide Deferred Taxation 3 1.4 If a charge for deferred taxation is included in the accounts, the profit and loss accounts appear as follows: Year Profit per accounts Corporate tax charge Deferred tax charge/(credit) Total tax charge Profit after tax Effective rate of tax 1 2 3 4 8 £ £ £ £ £ 2,000 2,000 2,000 2,000 2,000 200 200 400 280 120 400 344 _56 400 395 __5 400 1,600 1,600 1,600 1,600 1,600 20% 20% 20% 20% 20% 516 (116) 400 1.5 There are a range of timing adjustments apart from the differences between depreciation and capital allowances. It is the province of deferred tax to deal with such timing differences. 1.6 In Chapter 2, dealing with corporation tax, we used the example of Hauleigh Horsegear Limited: you will recall that we separated the adjustments in the tax computations between those which were absolute, as they increased the effective overall rate of tax, and those which were timing, as they had the effect of moving the profits into different periods for tax purposes. 29 TAX COVENANTS A PRACTICAL GUIDE A Scrutton Bland Guide Deferred Taxation 3 The tax computation is given below: Tax Computation £ Profit per accounts 1,500,000 Absolute adjustments Add: Disallowed legal costs Disallowed entertaining expenditure Profit plus absolute adjustments 42,000 ___58,000 1,600,000 Timing adjustments Add: Depreciation on plant, furniture and equipment Closing general bad debt provision Closing unpaid pension contribution Timing adjustments £ 392,000 270,000 110,000 (392,000) (270,000) (110,000) Less: Capital allowances Opening general bad debt provision Opening unpaid pension contribution Adjusted profit for the year (362,000) (350,000) __(80,000) 1,580,000 362,000 350,000 80,000 Less: Losses brought forward Taxable profits _(580,000) 1,000,000 580,000 _______ 600,000 Total timing differences Corporation Tax payable: £1,000,000 at 24% Deferred Tax charge: £600,000 at 24% Total tax charge 240,000 144,000 384,000 168,000 1.7 The deferred tax charge is £600,000 at 24%, which is £144,000. In order to understand this charge against profits, we need to understand its constituent parts: 1.7.1 the depreciation is £392,000 and the capital allowances are £362,000. The capital allowances and depreciation on plant, equipment vehicles, furniture, etc., are equal over the life of the asset: however, the charges in the accounts for this capital expenditure is at a different rate from that at which capital allowances are available. There is therefore a mismatch between the accounts and the tax treatment. 1.7.2 In earlier years the capital allowances will have exceeded the depreciation charge. So that these years did not gain the benefit of a lower tax charge, and knowing that the reverse would apply in the future, the reduced tax charge of that earlier year was increased by a deferred tax charge. The opposite now applies and there is a deferred tax credit of £30,000 (£392,000 - £362,000) at 24% which is £7,200. 30 TAX COVENANTS A PRACTICAL GUIDE A Scrutton Bland Guide Deferred Taxation 3 1.7.3 The closing bad debt provision is £270,000 but the opening bad debt provision was £350,000. The difference between the two is £80,000. As this provision was not treated as deductible for tax purposes when it was created, its release is similarly non taxable. A general bad debt provision should always reverse at some stage: it is either released to the profit and loss account, giving a tax-free boost, or it is allocated against specific debts, at which point it becomes a deductible provision. 1.7.4 When the general bad debt provision was created there was a charge in the profit and loss account but no tax relief granted. Therefore this triggered a deferred tax credit, in recognition that this credit would reverse when the general bad debt provision was released. There is a partial release in the current year and this therefore leads to a deferred tax charge of £80,000 at 24% which is £19,200. 1.7.5 The unpaid pension contribution works in a similar way: this is £110,000 at the year end and was £80,000 at the prior year end. By adding back the closing unpaid contribution and deducting the opening unpaid contribution the charge in the accounts is effectively switched from a matching or accruals basis onto a cash basis. Therefore the pension contributions which are deductible are those paid in the year which are £30,000 (£110,000 less £80,000) lower than those which were charged in the year. This therefore leads to a deferred tax credit of £30,000 at 24% which is £7,200. 1.7.6 The final adjustment for the year is in respect of the tax losses brought forward: these were £580,000 at the last year end. The Company had made losses in the two earlier years: the directors therefore recognised a tax credit in the accounts of the two years in which these losses had arisen. If they had not done this, the Company would have made a loss before taxation, with no tax credit in respect of those losses. Now that the losses are being utilised there is a deferred tax charge, which is computed as £580,000 at 24% which is £139,200. 1.8 We can therefore summarise the ingredients of the deferred tax charge in the year: Gross £ Depreciation in excess of capital allowances Decrease in general bad debt provision Increase in unpaid pension contribution Use of tax losses brought forward Total charge for year and increase in provision (30,000) 80,000 (30,000) 580,000 600,000 Net at 24% £ (7,200) 19,200 (7,200) 139,200 144,000 1.9 It is therefore the objective of deferred taxation to ensure that tax charges which are included in the accounts of various years are not distorted by the timing of reliefs which are given by the tax system. 1.10 Deferred taxation is never payable: the concept is that charges or credits appear in the profit and loss account as originating entries and they then reverse at a later date. 31 TAX COVENANTS A PRACTICAL GUIDE A Scrutton Bland Guide Deferred Taxation 3 1.11 The components of the deferred tax provision can be identified in any company, in a similar manner to that shown above. If we continue the above theme, and make an assumption as to the levels of the fixed assets and the capital allowance pools, the balance sheet representation of the above deferred tax charge is: This Year Gross Net £ £ Book amount of plant Less: Capital allowance pools 2,981,000 1,970,000 1,011,000 242,640 Next Year Gross Net £ £ 2,890,000 1,849,000 1,041,000 249,840 General bad debt provision (270,000) (64,800) (350,000) (84,000) Unpaid pension contributions (110,000) (26,400) (80,000) (19,200) __ 631,000 __ 151,440 (580,000) _31,000 (139,200) __7,440 Tax losses carried forward Total per balance sheet 1.12 The gross value of the balances in the deferred taxation account have increased by £600,000, from £31,000 to £631,000. The net balances have increased by £144,000, that is from £7,440 to £151,440. It may seem mysterious that these figures are identical to the figures in the tax computations. This is not a coincidence: it is an aspect of accounting that things balance. It is an aspect of deferred tax accounting that it works in this way. 1.13 You should be able to identify the rationale for the equilibrium in respect of the tax losses, the general bad debt provision and the pension liability. The transactions within the fixed assets and capital allowances are rather more opaque. However, we can confirm that the movements in respect of both the net book amount of the fixed assets and the capital allowance pools, will be consistent between the profit and loss account and the balance sheet. Such is the apparent alchemy of deferred tax accounting. 1.14 Happily there is no need for this to remain as alchemy: this occurs as the same figures are added to the capital allowance pool as are added to the net book amount of fixed assets in respect of additions. Regardless of rates of writing down allowance, the existence of long-life assets or short-life assets, the capital allowance pools will be increased in aggregate by the increase in the eligible fixed assets. In the same way, the disposal proceeds will be deducted from the capital allowance pools. The net book amount of the fixed assets will be reduced on the disposal of assets: the net book amount disposed of and the profit or loss on disposal will aggregate to the same as the proceeds. 32 TAX COVENANTS A PRACTICAL GUIDE A Scrutton Bland Guide Deferred Taxation 3 2 The Accounting Standards 2.1 It is very understandable that the legal profession has viewed deferred tax with a mixture of suspicion and hostility: deferred tax has been in existence for a considerable period, but there have been different accounting standards which have governed its use. 2.2 Much of the suspicion of deferred taxation, and the belief that it is entirely subjective in its application, and should therefore play no part in legal documents, is based on Statement of Standard Accounting Practice 15. This standard was wrestling with the problems arising from deferred tax accounting in times of high inflation. In the crucible of the 1970’s there were very high rates of inflation and also a front-end loading of capital allowances: 100% allowances were given in the year of acquisition of plant and equipment. In addition to this, for a period there was a tax allowance given for increases in the levels of closing stocks. These heady ingredients mixed to give a potent brew: the financial statements of companies trading in such times were showing ever-increasing deferred taxation provisions, with no apparent prospect of reversal. 2.3 The response to these challenges was SSAP 15: this enabled companies to follow a policy of partial provisioning. Provided that forecasts were produced which showed ever-increasing capital expenditure, no provision was needed for the tax arising in respect of the accelerated capital allowances. This then enabled the tax charge in the accounts to be lower than the headline rate: provided that there was a combination of relatively high levels of inflation and high levels of first year allowances, this gave a better reflection of the effective rate of tax being paid by capital-intensive companies. 2.4 The subjectivity inherent within SSAP 15 inevitably meant that it was viewed with some considerable caution: different assumptions in budgets could have a material impact on the amounts of deferred tax that were provided in the financial statements. It was therefore perhaps no surprise that the deferred tax provision was given a wide berth by those dealing with Tax Covenants. 2.5 By the late 1990’s the climate had altered markedly: inflation had reduced very considerably and the regime of greatly accelerated capital allowances had been largely dismantled. The front-end loading of the tax allowances was therefore far less prevalent than previously. These conditions provided the backdrop for Financial Reporting Standard 19 which was introduced in December 2000. This standard requires full provisions to be made for deferred tax. It also introduced the facility for deferred tax balances to be both net liabilities and net assets. 2.6 There are still three areas of choice or subjectivity that exist within FRS 19, but their impact is now very much reduced, as they do not affect the core of the Standard: 2.6.1 there is a choice as to whether or not to discount the components of the deferred tax account for the time value of money This may be appropriate when dealing with very long-life assets. Apart from this, discounting is unlikely to be material; 2.6.2 the second area of subjectivity is in respect of tax which may be deferred by rollover relief, depending on future plans. Provision should not be made for deferred tax which is to be deferred by rollover relief; 33 TAX COVENANTS A PRACTICAL GUIDE A Scrutton Bland Guide Deferred Taxation 3 2.6.3 if there is a deferred tax asset it should be recognised if it is more likely than not that there will be taxable profits in the future against which the deferred tax asset can be offset. 2.7 Evidence of the lack of subjectivity is given by the opening paragraph of FRS 19 which states: “Financial Reporting Standard 19 “Deferred Tax” requires full provision to be made for deferred tax assets and liabilities arising from timing differences between the recognition of gains and losses in the financial statements and their recognition in a tax computation.” 2.8 In the examples given above of Rickinghall Printers Limited and Hauleigh Horsegear Limited there are no subjectivities involved: the composition of the deferred tax account is determined by the underlying facts; it is not coloured by any judgements. 2.9 IAS 12 has a very similar structure to FRS 19. There is one main area of difference and that is that IAS 12 gives itself a wider scope. IAS 12 requires that tax is provided on the uplift in value of fixed assets which have been revalued, whereas this is not permitted under FRS 19. There is also a slight difference in the terminology which reflects this different approach: FRS 19 refers to “timing differences”, whereas IAS 12 uses the phrase “temporary differences” as it seeks to embrace all differences between the carrying amount of assets and liabilities and their tax base. 2.10 Under IAS 12 the viewpoint from which deferred tax is surveyed is the balance sheet: if a property is revalued this creates a temporary difference: a temporary difference is a difference between the carrying amount of an asset or liability and its respective tax base. Under IAS 12 there is a requirement that a provision for deferred tax is made in respect of that valuation difference. 2.11 The conceptual basis of FRS 19 is that of recognising a liability when it arises: no liability arises when a property is revalued as this does not trigger a tax charge. Such a charge only arises on sale. With IAS 12 the central concept is that of ultimate realisation: every asset will be realised over time, either by consumption as its value is gradually used up, or by disposal. The recognition of temporary differences under IAS 12 is based on this theme of ultimate realisation. 2.12 It can therefore be seen that IAS 12 has a broader compass: it picks up many of the liabilities which are the concern of tax warranties, such as tax base costs of assets which are lower than the book amounts. 2.13 The discounting of deferred tax liabilities is not permitted under IAS 12. 3 Timing Differences 3.1 We have already introduced some of the more common timing differences, namely: 3.1.1 the difference between depreciation of fixed assets and the tax allowances given; 3.1.2 taxed provisions, that is provisions in the accounts which are not deductible for tax purposes; 3.1.3 tax losses carried forward to a later period. 34 TAX COVENANTS A PRACTICAL GUIDE A Scrutton Bland Guide Deferred Taxation 3 3.2 There are several other types of timing difference and we will examine some of these below. 3.3 If interest is capitalised as part of the cost of a fixed asset, or as part of the cost of stock, such as on a large building project, it is still deductible for tax purposes as if it had been charged directly to the profit and loss account. Such interest is therefore a timing difference: the tax benefit arising from the interest expense has to be deferred in the same way that the cost of the interest has been deferred. As the fixed asset is then depreciated, this timing difference effectively reverses, as the interest is then effectively charged to the profit and loss account by means of an increased depreciation charge. A similar concept applies to the stock: at the point when the cost of the stock, including the interest component, is recognised in the profit and loss account as a component of cost of sales, then the timing difference reverses. 3.4 It is very possible that smaller items of capital expenditure may be written off to repairs. If this happens it is necessary for the repair cost to be disallowed, and for capital allowances to be claimed instead. This is therefore another type of timing difference affecting fixed assets. 3.5 With defined benefit pension schemes (more commonly known as final salary schemes) there is a requirement under FRS 17 to include on the balance sheet the amount of the surplus or deficit in the pension scheme. The profit and loss account should include the cost relating to providing the benefits relating to that period. This amount is determined by the actuary and may be far removed from the contributions actually paid to the scheme in the year. For various reasons the deferred tax effects from this treatment are shown as part of the FRS 17 provision on the balance sheet. 3.6 The accounts of each company in a group will record its stocks of goods for resale at the lower of cost or net realisable value. These measures will be applied to each company as a separate entity. If chemicals are manufactured or bought by Stanton Chemicals Limited for £8 per litre and then sold to its wholly owned subsidiary, Ixworth Cleaning Limited for £10 per litre, the individual accounts will record the cost of the chemicals at £8 and £10 respectively. If Ixworth Cleaning Limited has 60,000 litres in stock at the year end, it will therefore record these in its accounts at a cost of £600,000. However, if consolidated accounts are produced, the profits of £120,000 made by Stanton Chemicals Limited are unrealised as the stocks have not yet left the group - they remain on the balance sheet of Ixworth Cleaning Limited at a value which includes a profit of £120,000. For the consolidated accounts these stocks are therefore reduced in value from £600,000 to £480,000. Tax has however crystallised in Stanton Chemicals Limited in respect of the profits made on these sales. This tax has crystallised before the profit is realised in group terms, and therefore the charge is deferred to the next period (for accounting purposes only), when the stocks will be sold. 3.7 It should be noted that, under UK GAAP, the revaluation of a fixed asset does not result in the recognition of a deferred tax liability, representing the tax on the uplift in value. The reason for this is that this is not consistent with the conceptual framework on which UK GAAP is built. The act of revaluation has no discernible effect on the tax liabilities of the company. There is deferred tax under IFRS on such a revaluation. 3.8 If however a company follows a policy of continuous revaluation of assets, such as the use of a mark to market approach, then the tax timing differences should be recognised. 35 TAX COVENANTS A PRACTICAL GUIDE A Scrutton Bland Guide Deferred Taxation 3 3.9 Tax that could be payable on any future remittance of the past earnings of an overseas subsidiary or joint venture should be provided for only to the extent that dividends have been treated as receivable in the UK. 4 The Discounting of Deferred Tax Liabilities 4.1 Liabilities are normally recorded in financial statements at the amount at which they are to be settled. They are not usually discounted to reflect any delay in their settlement. This makes eminent sense as most liabilities are either to be settled within a relatively short period of the year end or they are entitled to interest to reflect the delay in their settlement. There are one or two exceptions to this basic rule: one of these is in respect of pension fund liabilities. These are normally long-term liabilities and they may have an average payment date of 16 or more years. When accounting for pension fund obligations the future liabilities are discounted by the actuary to reflect the time period until settlement. 4.2 A second example where discounting may be applied is in respect of deferred tax liabilities: this is permitted but is not obligatory under FRS 19. Discounting is normally only appropriate when it makes a material difference. This will normally arise when the timing differences may not reverse for some considerable period such as with very long life assets. 4.3 We are not exploring the mechanics of the discounting of deferred tax liabilities. However, it is important to understand whether or not the Company has discounted the deferred tax provision for the time value of money. This should be evident from the accounting policies or the other notes to the financial statements. 5 Deferred Tax Relief - One of the Buyer’s Reliefs 5.1 The classic Tax Covenant generally steers well clear of deferred taxation balances. One of the exceptions is that the asset components of the deferred tax account are recognised by the Buyer as being of value: therefore the protection of the Tax Covenant is extended to embrace them. This is done by including such assets within the definition of a Buyer’s Relief. There are four components to the classic definition of Buyer’s Relief, and the first one is: (a) any Relief to the extent that such Relief has been taken into account in computing and so reducing or eliminating any provision for deferred Tax which appears in the Completion Accounts, or which but for such Relief would have appeared in the Completion Accounts or was taken into account in computing any deferred Tax asset which appears in the Completion Accounts (“Deferred Tax Relief”). 36 TAX COVENANTS A PRACTICAL GUIDE A Scrutton Bland Guide Deferred Taxation 3 5.2 If we return to the example of Hauleigh Horsegear Limited, the gross and net values of the asset components of the deferred tax account in the previous year are: Capital allowance pools General bad debt provision Unpaid pension contributions Tax losses carried forward Total Gross £ Net at 24% £ 1,849,000 350,000 80,000 __580,000 2,859,000 443,760 84,000 19,200 _139,200 686,160 5.3 Therefore if the shares in Hauleigh Horsegear Limited had been sold sometime after the date of the accounts of the previous year, then the above balances would have represented the Deferred Tax Relief component of Buyer’s Relief. This is on the assumption that the transaction did not involve completion accounts. 5.4 It is understandable that the Buyer wants the protection of the Tax Covenant extended to cover these amounts: the level of the tax losses carried forward may well have featured in his assessment of value when negotiating the price for the shares. 5.5 The impact of the loss of a Deferred Tax Relief is dealt with in the definition of Tax Liability, which is stated to include: i) the loss, utilisation or reduction of any Deferred Tax Relief which would (were it not for the said loss, utilisation or reduction) have been available to the Company in which case the amount of the Tax Liability will be the amount of Tax which would have been saved if the Deferred Tax Relief had been available; 5.6 We can therefore explore some of the possible events which may result in a loss of a Deferred Tax Relief. 5.7 If it is identified after Completion that there had been a casting error in the capital allowance pool calculations, with the effect that the pool balances were overstated by £100,000, then this would enable a claim to be made under the Tax Covenant: if the pool had been at the level anticipated the extra capital allowances in the first 4 years would have been £20,000, £16,000, £12,800 and £10,240 respectively. The taxable profits would therefore have been reduced by these amounts and the corporation tax that would have been saved, at a rate of 24%, would have been £4,800, £3,840, £3,072, and £2,458 respectively. The overall value of this loss of a Deferred Tax Relief at a corporation tax rate of 24% is clearly £24,000, yet recovery of only £14,170 has been made in the four years after Completion. As the pool balance halves in value every 3.12 years at an allowance rate of 20%, it takes 6.2 years to recover three-quarters of the pool and 9.4 years to recover seven-eighths, that is 87.5%. 37 TAX COVENANTS A PRACTICAL GUIDE A Scrutton Bland Guide Deferred Taxation 3 5.8 There is nothing particularly unjust in the above approach: this is the way that the tax would have worked in practice, if the capital allowance pool had been greater to the extent of £100,000. It does, however, place quite a record-keeping burden on the Company: there is a need to maintain a record of the actual capital allowance pool as part of the tax computations. There is then also a need to maintain a shadow pool, so as to track the use of the Buyer’s Relief. 5.9 There are occasions when the Tax Covenant is worded in such a way that the loss of a Deferred Tax Relief is measured on the assumption that there were sufficient profits to allow the whole of the Relief to be used in the first accounting period after Completion. This is not an acceptable clause as it means that the Buyer gains a benefit which may be greatly accelerated: it is likely to put him in a better position than he would have been in any event. 5.10 Such wording as described above may not enable the whole of the benefit to be accelerated in any event: in the above example it is not a dearth of profits which delays the recovery of the Deferred Tax Relief - it is the operation of the taxing statutes. The above wording therefore creates difficulties in interpretation unless it is also stated that it should be assumed that the lost Reliefs are immediately available, rather than being available in accordance with the tax legislation. 5.11 If the tax computations are reviewed and amended after Completion, with £50,000 of the general bad debt provision being allocated to specific doubtful balances, then the effect will be that there will be a reduction of one Deferred Tax Relief (as the general bad debt provision will now be £300,000, rather than £350,000) but there will be an increase in another, namely the tax losses carried forward, which will have increased by £50,000, from £580,000 to £630,000. 5.12 There has been a reduction of a Deferred Tax Relief, so the Buyer is able to recover under the Tax Covenant. If the timing of recovery is on the assumption that profits are sufficient to enable full utilisation of the Deferred Tax Relief, then there is an immediate claim possible for £50,000 at 24%. 5.13 In this circumstance a Corresponding Saving would then also arise, as the increase in the tax losses is a direct result of the decrease in the general bad debt provision. The same would prevail if the loss only resulted in a payment at the time when the additional tax was payable. There will always be some uncertainty as to when general bad debt provisions should be considered to be used, as this is largely at the behest of the Buyer. 6 The Deferred Tax Liabilities 6.1 It is an accident of evolution that Tax Covenants concern themselves with deferred tax assets, but give no regard to deferred tax liabilities. 6.2 Liability balances in the deferred tax account include: 6.2.1 the book amount of those fixed assets which are eligible for capital allowances (or the net of this figure and the capital allowance pool for those who consider that the separation of these two components is artificial, on the basis that it is the difference between them that is the figure in the deferred tax account); 38 TAX COVENANTS A PRACTICAL GUIDE A Scrutton Bland Guide Deferred Taxation 3 6.2.2 profits which have been included in the accounts but which have not yet been taxed, such as profits recognised in consolidated financial statements in respect of overseas operations, and which have therefore not been subject to UK tax; 6.2.3 costs which have been allowed for tax but which have not yet been recognised in the profit and loss account, such as interest costs which have been capitalised or carried in a work in progress balance; 6.2.4 under IFRS the deferred tax provision in respect of the revaluation of a property; 6.3 From the viewpoint of the Seller it seems inconsistent that the Seller is punished if a deferred tax asset is overstated, but there is no mechanism for a recovery if the deferred tax asset is understated, or a deferred tax liability overprovided. 6.4 Viewed from the perspective of the Buyer he can bring the full power of the Tax Covenant to bear if a deferred tax asset is understated, but he has to rely on the protection of the warranties if a deferred tax liability is underprovided. 6.5 We therefore need to consider whether Tax Covenants should address deferred taxation in a different way: should we treat deferred tax balances, whether asset or liability, on a consistent basis? 6.6 The answer to this question should be, in our opinion, a guarded but certain “yes”. It is our view that the concentration on the cash flow effects of tax payments can be an elegant means of ensuring equity between the two parties: there is an absolute certainty to cash receipts and payments which is comforting. Having said that, it is rather odd that claims can be made under the Tax Covenant for a loss, when there has been no reduction in the net assets of the Company: for most purposes it is the reduction in the value of the Company or in its level of the net assets which is the measure of loss that might be expected. If a corporate tax provision is found to be understated, it is very likely that the deferred tax provision will be overstated by the same amount, if it relates to a timing adjustment. 6.7 We fully recognise that there are some capital-intensive companies where the timing of tax payments is a matter of some importance, and where a switch from deferred tax provisions to corporate tax liabilities is a material issue. However, there are very many corporate transactions where this is not so: the business is not capitalintensive and the drivers of value have been the profit forecasts, with the multiplier being coloured by the extent of the asset backing. In such cases it matters little in terms of value what the split is on the balance sheet between the corporate tax liability and the deferred tax provision: a transfer between the two would not have had any appreciable impact on the price or the value received by the Buyer. 6.8 This is a matter on which this publication is engaged in missionary work: we believe that the burden of post-completion record keeping when there are claims under the Tax Covenant in respect of timing differences is likely to be totally disproportionate in the majority of cases. In such cases we are of the view that there should be a different approach to the Tax Covenant. In Chapter 19 we have included a Tax Covenant prepared on the basis that timing differences are ignored. The Buyer does not claim under the Tax Covenant if an increased tax liability now is effectively matched by an identical saving some time later. 39 TAX COVENANTS A PRACTICAL GUIDE A Scrutton Bland Guide Deferred Taxation 3 6.9 The main effects of this change are: 6.9.1 the protection for the Buyer is now extended, so that a claim can be made if it is found that a provision for deferred tax is insufficient in the Last Accounts or the Completion Accounts; 6.9.2 the cost of confirming the existence of corresponding savings is now much reduced, to the significant benefit of the Covenantors: many corresponding savings, in respect of timing differences, will be a thing of the past; 6.9.3 the focus of the Tax Covenant will be to provide protection to the Buyer in respect of Tax Liabilities broadly by reference to the reduction which has occurred to the net assets arising from the additional tax in question; 6.9.4 the Buyer will not be burdened with making a series of claims in respect of a loss of a Deferred Tax Relief if the loss relates to the reduction in the capital allowance pools. 6.10 Due to this approach giving immediate credit for tax losses, it will not be appropriate if the tax losses carried forward at Completion are material when compared to the size of the transaction. 40