History of Dining Services at James Madison University

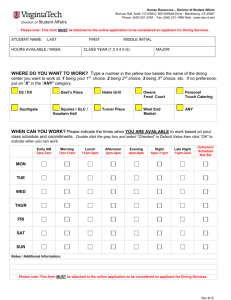

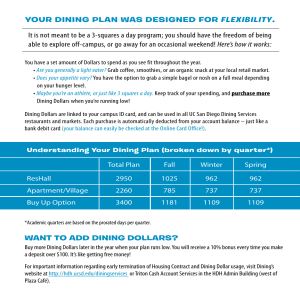

advertisement