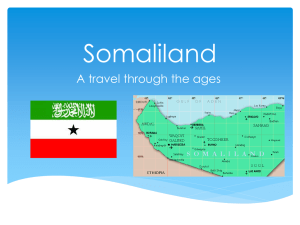

Self-Determination and Secessionism in Somaliland and

advertisement