The Battle Of Coachella Valley by David Harris 1973

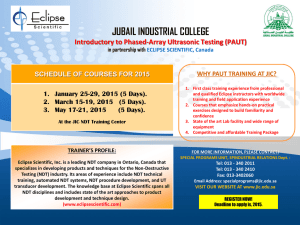

advertisement

The Battle Of Coachella Valley by David Harris 1973 (Published in Rolling Stone Magazine. September 13, 1973.) Alicia Uribe remembers the 16th of April like she remembers her feet or the fingers on her hands. The day is built into her body now. It has been ever since it first happened. She and a hundred others started the 16th lined along the hot dirt shoulder in front of he Mel-Pak vineyards. The road behind them slid six greasy miles east to Coachella and Indio. Alicia cocked her union flag over her arm and let it slop sideways like wash on the line. The 90 degrees around her kept lifting off the valley floor in thin slabs. Each way Alicia looked, the world had a warp to it and a shimmer, like the air was dribbling sweat. The1 6 t hdi dn’ tf e e l a l l t ha tdifferent from any other spring day in the Coachella Valley. At ten, the heat pushes past a hundred and the asphalt on the far side of noon bubbles like c or nme a lmu s h.Thr e eo’ c l oc kc ook ss pi tbe f or ei tha sac ha nc et ot ou c hg r ou nd.Wi t hou t deep wells and old age, the Coachella Valley would be one long griddle of sand, anchored with greasewood and horned toads. As it is, 40,000 people live along its bottom and rising sides. The old ones built Palm Springs to comfort their rich arthritis; the young ones dug enough deep wells to cover patches from the San Jacinto Mountains to the Salton Sea with grapes, date palms, grapefruit, melons and sweet corn. If it were a year like any other, Alicia Ur i bea ndhe rhu ndr e df r i e ndswou l d’ v ebe e nu pt ot he i rs hou l de r si nThompson Seedless. But 1973 hit the east end of Riverside County like a bizarre snowstorm. The trouble and the crops came in together. A lot of folks guessed the trouble was coming, but no one knew it would show up quite the way it did. From the 16th on, the Coachella harvest was a spl a i na st henos eonAl i c i aUr i be ’ sf a c e . She remembers a red pickup truck and a white sedan spitting rooster tails behind their tires. The two shapes bounced along the ranch road, through the fields, and towards their line. “ LosTe a ms t e r s , ”t hewoma nne x tt ohe rs a i d. As the word jumped from ear to ear, the pickets began shouting and waving their red and black flags. The truck pulled even with Alicia and a fat man in the passenger seat jerked a .38 out of his pants. He let the sand billow over the tailgate and used his mouth to shout back. “ Ea ts hi t , ”t hef a tma nr u mbl e d. Thewhi t es e da ns l u mpi nga l ongi nt hef a tma n’ st r a c k swa sq u i e t .I t su phol s t e r ywa s covered with four men in clean shirts. Making a sudden skip on the loose dirt, the car swerved right and one of the shirts in the back window leaned out and laid a parr of brass k nu c k l e sa l ongt hes i deofAl i c i aUr i be ’ she a d.Ev e rs i nc e ,he rf a c eha sha dal i t t l ede ntt o i t .Thebl ow f r a c t u r e dAl i c i a ’ sc he e k ,br ok ehe rnos ea nddug a scratch across her right eyeball. The white sedan turned left and disappeared towards Palm Springs. Lying there in hot sand mixed with her splatter of 19-year-old blood, Alicia Uribe be c a met hef i r s tc a s u a l t yi nawa rt ha t ’ sbu bbl e dou tofe v e r yt i n-roofed shed within 40 miles of downtown Indio. The fight is all about grapes and the people who pick them. It ha st hr e epa r t i e sa ndt wos i de s .Ont heoneha ndi sAl i c i aUr i be ’ s6 0 , 0 0 0me mbe rUni t e d Farmworkers Union, AFL-CIO. Their three-year contract with the desert grape industry e x pi r e dApr i l1 5 t h.Ont heot he r ,t he2 7g r owe r swhoownt heVa l l e y ’ s7 1 0 0a c r e soft a bl e grapes sit with the 2,000,000 member International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Chauffeurs, Warehousemen and Helpers of America. The Teamsters own the red pickup, the white sedan, the brass knuckles and a fresh set of contracts which give them claim to represent t heVa l l e y ’ s3 5 0 0v i ne y a r dwor k e r s .TheI nt e r na t i ona lBr ot he r hooda ndt heg r owe r sha v e signed each other up and the UFW is striking the m bot h.I t ’ snots ma l lf i g ht .Be f or et he s u mme r ’ sov e r ,i tc ou l dg r i ndi t swa ya c r os sAme r i c a ’ spr odu c ec ou nt e r sa ndpe r ha pse v e n reach the outskirts of Washington, D.C. Noneoft hi swou l dbeha ppe ni ngi fi twe r e n’ tf ort heUni t e dFa r mwor k e r s . Te ny e a r sago, t he ywe r eat r u c k s t opj ok eu pa nddownHi g hwa y9 9 ,now t he y ’ r ea l lna t i ona l l yk nown. The r ewe r el ot sofr e a s onsf ort heu ni on’ sr i s e ,bu tt hebi g g e s twa st hepur ea nds i mpl e need for it. Since the Okies left to fight World War II, farm labor had belonged to a lot of Mexicans and a few Filipinos and Arabs. Telling one from the other was hard if you just l ook e da tc he c ks t u bs . Thes ou t hwe s tha dawhi t ema n’ swa g e , aMe x i c a nwa g e , a ndal otof distance in between. Most Americans paid little attention, holding comfort in the k nowl e dg et ha tMe x i c a nsdi dn’ tne e dmu c hmone ys e e i nga showt hepr i c eofbe a nswa ss o cheap. White folks commonly understood dollars were a fortune in Spanish and trusted the honky legend that was sure all the wetbacks took their earnings south and bought steel mills on the outskirts of Tijuana. Asar e s u l t , t hena t i on’ s3 , 0 0 0 , 0 0 0a g r i c u l t u r a l l a bor e r swor k e da na v e r a g eof1 1 9da y sa year with an annual wage of $1389. One out of every three farmworker houses had no toilet, one out of every four no running water. The average worker lived to be 49 years old and a thousand a year died from pesticide poisoning in the fields. If there was anything the people with those lives needed, it was a union. And they knew it. Since the Spanish missions , Ca l i f or ni a ’ spr odu c eha sbe e nwor k e dby people who followed their dreams across a border and figured they deserved a whole lot better than they ended up getting. In 1884, Chinese hop pickers waged the first strike in Kern County. They asked for $1.50 a day and ended up with an ass-whipping and a broken union. After that it was more of the same. Growers are very powerful people with big bags of money, and a command of both the language and the local police. At the same time, the world is full of people who are hungry, poor and desperate enough to chase their dreams t oCa l i f or ni a .Tog e t he r ,t het woma k eama g i cc ombi na t i ona l lt hewa yt ot heg r owe r ’ s ba nk .Onc ey ou ’ v epa i dy ou rl a s tpe s ot og e tt hr e e ,Ca l i f or ni a ’ saha r dpl a c et og e tba c k from and an easy place to starve. Over the years, the bosses have made a practice of hiring ane wdr e a mi fy ou r sg e t ss l oworu ppi t y .Thet e c hni q u e ’ sbe e ne nou g ht oma k eal otof folks swallow their bitch and tote that sack. The man who signs the paycheck is called “ y a s s u h, bos s ”a ndt ha nk e df ort heoppor t u ni t yt os we a ti nhi sf i e l ds . Filipinos, Japanese, blacks, Mexicans, Okies and Arabs all followed in the Chinese footsteps. The IWW tried to organize a union, the CIO tried, the AFL tried and then the AFL-CIO tried again. All of those efforts failed. When the National Labor Relations Act recognized the right of working men to form unions, farm labor was excluded. Each succeeding minimum wage bill had agriculture in a special place all to itself. Some growers took to economizing by dropping wages every time they broke a strike. For a man picking grapes, 1884 and the 1962 Delano that Cesar Chavez drove into looked a lot alike. Farmworkers used just one picture for both their pasts and futures. It was worn on the edges, sore and ate whenever it could. Not that Chavez was shocked. That life had been his feet and ribs since his family lost their Arizona farm in 1938. Cesar and the Chavezes moved the length of California, living in hovels, missing shoes in the winter and working when the labor contracto4 said it was all right. By 1952, Chavez lost his patience, went for a break in the clouds and became an organizer for the Community Services Organization at $35 a week. He did that for the next ten years. Chavez wanted to go into rural California and build a union, but the CSO de c i de da g a i ns ti t .S oCe s a rt ookhi s1 9 6 2l i f es a v i ng sof$ 9 0 0a ndwe ntt ohi sbr ot he r ’ s house in the San Joaquin Valley. Thedr e a mi nCha v e z ’mi ndt ookr ooti nt i nyhou s e s ,wi t hwha t e v e rc i r c l eofwor k e r s could be collected. When the talking was over, the hat made its way around the room and Cesar lived out of it, picking grapes each time the sombrero came back light. Soon the hosue meetings called themselves the Farmworkers Association. By 1965, the organization supported itself, with dues and fought two small strikes. Then the dream blossomed. In September of that same years, the Filipino Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee came to Delano to work grapes and had no taste for the $1.20 an hour being offered. AWOC struck and the FWA had to stand on one side or another. Eight days after the Filipinos set up their pickets, the Farmworkers Association voted unanimously to jump in with both feet. Together, they called themselves the United Farmworkers and started off i nt ot hebi g g e s tf i g htt he y ’ de v e ri ma g i ne d . The UFW spent five years on strike and boycotting to win their original contracts with t het a bl eg r a pei ndu s t r y . Be f or et heUni on’ sv i c t or y , ba s ewa g ei ng r a pe swa s$ 1 . 2 0a nhou r with a ten to 20¢ kickback to the labor contractor. The 1970 union agreement started at $2.05 and created the first hiring hall in grape-growing history. It also forced the growers to a c c e ptpe s t i c i der e g u l a t i onsmu c hs t i f f e rt ha nt hes t a t eofCa l i f or ni a ’ s ,a ne mpl oy e r financed health plan, banning workers under 16, and no firing without just cause. The c ont r a c tl a s t e dt hr e ey e a r s .Toda y ’ st r ou bl e ss t a r t e dwhe ni tc a met i met os i g nane wone : Ne g ot i a t i onsne v e rpa s s e dt hef i r s tpoi ntofdi s c u s s i on.I twa s n’ tj u s tt heu ni on’ spr oposal t heg r owe r sdi dn’ tl i k e .Mos toft he m pl a i nc ou l dn’ ts t a ndt heu ni on.“ I t ’ st oog odda mn de moc r a t i c , ”a st hewa yonede s c r i be di t . TheUni t e dFa r mwor k e r sdon’ ts e ndt he i rpr e s i de nti nt og e tac ont r a c thec a n announce to everybody else. All union members are on crew committees which elect representatives to a ranch committee and the ranch committee negotiates. At contract time, that means the growers sit face to face in a $50 hotel room with the people who work for them, listening to them talk in Mexican and eventually giving in—none of which are too popu l a ra mongr i c hg r owe r sa ndc or por a t i ons .Whe nt het a l k ss t a r t e dt hi sy e a r ,i twa s n’ t long before the UFW understood the growers had Teamster contracts in their pockets and the tiny United Farmworkers was in for a brawl with the largest union in the Western world. “ TheTe a ms t e r sa ndg r owe r sha v ebe e nj oi ne dt og e t he r , ”Cha v e z ,nowUFW na t i ona l c ha i r ma ne x pl a i ns . “ The ya r et r y i ngt ode s t r oyou runi ona ndf or c et hewor k e r st oa c c e pta u ni ont he ydon’ twa nt . ”Fort hi swor ka sc ha i r ma n,Cha v e zr e c e i v e s$ 5awe e kpl u sf ood, g a sa nds he l t e r .Tol ooka thi m,y ouwou l dn’ tt hi nkCha v e zha sa na g e .Hi sf a c ei sf u l lof soft creases sitting sidesaddle on a collection of bumps. Behind it, his mind perches on his shortbody ,f l i c k i ng ,wa t c hi nga ndpoi s e dl i k eac a t .Andt ha t ’ sa l lofCe s a rCha v e zt ha t s hows .The r e ’ smor e ,t obes u r e ,bu tt her e s tha st u r ne di noni t s e l f ,g r owni nt oi t sda r k brown toot, stewed there, and sprouted into a crowd of red and black eagle flags. Chavez is more than meets the eye and less than a nation of movie magazines and talk shows has come to expect. He gets up in the morning and scratches himself like everybody else, but t hebou nda r i e swec a l lpe r s ona l i t ya r e n’ ts os ha r pl ydr a wn.I ns omes trange way, Cesar Cha v e zdoe s n’ te x i s t .Hi sl a u g ht e ra ndt hef e a ronhi se y e l i dsa r ehi sown,bu tt hes ha dow he casts has long since become the shape of a long sweating line inching out of Mexico. When he talks, the voice always sounds bigger than the face it speaks with; it is as though the words come from somewhere over his shoulder. Chavez behaves like a bulge in the hi deofat hou s a ndy e a r s ’hi s t or y .Whe nhel ook su p,hes e e mse mba r r a s s e dbyi ta l l .The nerves in his fingers betray him. They grapple with each other under his conversation. The words glide along in their own self-conscious way, full of stumbles and wide enough to t ou c ht hee a r sofe v e r yLope zi nCa l i f or ni a .He ’ st hel e a de rofhi spe opl emor et ha nhei s anything else. The most on the surface is Cesar Chavez, but the stuffings are 100% union. It makes him hard to know and easy to believe. Over the years, Chavez has acquired the habit of meaning most everything he says. He c a l l st heTe a ms t e rmov e“ f e a r f u la nddi s hone s t . ”“ The y ’ r ea f r a i doft hef a r mwor k e r , ”he e x pl a i ns , “ be c a u s et he ydon’ tc ont r ol hi m. ” “ Weha v eof f e r e de l e c t i onst ol e tt hewor k e r sde c i dewhi c hu ni ont he ywa nt ,i fa ny . The Teamsters have refused and the growers, of course, have held out. They know if the workers are given the choice, they will be put out of the fields by a very large majority. Instead, the Teamsters hired goons in Los Angeles and brought them to Coachella with the i de aofs c a r i ngou rpi c k e t sa wa y .The y ’ r es l owl yf i ndi ngt ha tt hewor k e r sa r enota f r a i dof t he m. ” “ Ic a nu nd e r s t a ndt hee mpl oy e r s , ”Cha v e zc ont i nu e s . The y ’ r ee mpl oy e r sa nda c t i ngl i k e e mpl oy e r s .Whe ni tc ome st ot heTe a ms t e r sUni on,t ha t ’ sadi f f e r e ntq u e s t i on.The y ’ r e supposed to be a union and are acting in concert with the growers to destroy us. It ’ sa s ha me f u l a c ta ndt he ywon’ ts u c c e e d. “ TheTe a ms t e r sc l a i mt oha v es i g ne d4 5 0 0wor k e r si nt heCoa c he l l aVa l l e y .Wek no w t he yha v e n’ t , ”Cha v e zc hu c k l e s .“ The r ea r e n’ t4 5 0 0g r a pewor k e r si nt heVa l l e y .Yous e e , t heTe a ms t e r sdon’ tor g a ni z ewor k e r s . The yor g a ni z ee mpl oy e r s . The y ’ r ev e r ys u c c e s s f u la t or g a ni z i nge mpl oy e r sbu tv e r yba da tor g a ni z i ngwor k e r s . ” George Meany, President of the AFL-CIO, put it more simply in his own stern tone. Heg otonABCe v e ni ngne wsa ndc a l l e dt heTe a ms t e r s“ s t r i k ebr e a k e r s . ” When Teamster President Frank Fitzsimmons heard the comment, he announced on na t i onwi det e l e v i s i ont hene x tni g htt ha tMe a nywa s“ s e ni l e . ”I twa sas ma r tmov e .I fhe ha dn’ tc hos e nt ha tt a c k ,Fi t z s i mmonsmi g htha v eha dt os t a ndont heTe a ms t e rr e c or d, whi c hi s n’ tav e r ys ma r tt hi ngt odo.Ofc ou r s e ,Fr a nkFi t z s i mmonsdi dn’ tg e twhe r ehei s bybe i nga ny body ’ sdu mmy .Hi spr e s i de nt i a lpa y c he c kr e a ds$ 1 7 5 , 0 0 0ay e a r ,pl u st r a v e l and maintenance for himself and his wife. Teamster national headquarters is equipped with a limousine plus drive, a full-time barber, a full-time masseur, and two French chefs, not to me nt i ont hepr e s i de nt ’ spr i v a t e1 7 -s e a tj e t .Al lt ha t ,ofc ou r s e ,doe s n’ tc ha ng et heu ni on’ s record, starting with the president and working its way down. Fi t z s i mmons ’pr e de c e s s or ,J i mmyHof f a ,ha dapr obl e mc ommont oTe a ms t e rhi s t or y . He was sentenced to 15 years in a federal penitentiary for tampering with a jury. (His sentence was later commuted by Richard Nixon.) Since taking the reins, Fitzsimmons has had his own brushes with the law. Last February, an FBI stakeout spotted him meeting with alleged L.A. Mafia members Peter Milano and Sam Sciortino at the Bob Hope Golf Classic in Palm Springs. Before the golf balls were gone, Fitzsimmons had talked with Lou Rosanova, allegedly of the Chicago Mob, as well. Four days latger, he and Rosanova met again at a health spa in San Diego County. When their meeting was over, Fitzsimmons went north to San Clemente and hitched a ride back to Washing to with Richard Nixon on Air Force 1. Wiretaps later revealed a contract in the offing allegedly designed to bleed the u ni onpe ns i onf u ndwi t haMa f i ahe a l t hc a r epl a n. TheMob’ sk i c k ba c kwa sr e por t e da t7 %. When it came time to renew the wiretaps, Attorney General Richard Kleindienst refused permission and the investigation was dropped. Some said it was a case of the old Teamster solution again. The Teamsters were the first union to endorse the Republican ticket and rumors in Washington hold that Fitzsimmons had veto rights on the Secretary of Labor. The Manchester, New Hampshire, Union Leader has charged that the Teamsters invested better than half a million dollars in the secret Watergate campaign fund. When Special Counsel to the President, Charles Colson, retired from public life a few months back, he joined a Washington law firm that ha dbe g u nha ndl i ngt heTe a ms t e r s ’s e v e n-figure business just the month before. Needless to say, Fitzsimmons, Kleindienst, Colson, Milano, Sciortino and Rosanova have denied all charges of wrongdoing. At the bottom rung of the International Brotherhood, the record is no better. The Teamsters had no foothold in field work until the last half of 1970. Two days after the UFW won industry-wide contracts in grapes, the Teamsters signed five-year agreements with a frightened set of Salinas lettuce growers. The UFW responded by shutting down the lettuce fields with a walkout of 7000 workers. When the Teamsters appealed to the courts to invoke California labor law and stop the UFW from striking, they won an initial injunction. Two years later, the California Supreme Court reversed the findings of the lower courts. The justices ruled that the law forcing compulsory arbitration only applied to two unions representing factions of the same working for c e .Thec ou r tf ou ndt hei nt e r na t i ona lu ni ong u i l t yofa c c e pt i ngt heg r owe r ’ s invitation and making deals without worker representation. The Teamsters were, in the t e r msoft hel a w,r u l e da“ c ompa nyu ni on, ”or g a ni z e dbyt hema na g e me ntt odot he ma na g e me nt ’ s bidding. S i nc et heTe a ms t e r sa r r i v e di nS a l i na s ,t hr e eoft he i r“ or g a ni z e r s ”ha v ebe e nc ha r g e d with violation of the Firearms Act of 1968; half a dozen more are in court charged with felonious assault. Teamster Frank Corolla has told the federal grand jury that grower representatives delivered $5000 packets of fresh bills to Teamster officials each week at the Salinas airport. The only agricultural successes the Teamsters have enjoyed are in the packing sheds and canneries, both of which are under uncontested Teamster jurisdiction. Even on its own turf, the big union has had its problems. Committees of Chicano workers have formed in the canneries all over California. One recently filed 36 charges of racism against the Western Conference of Teamsters. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission upheld all 36 and issued a cease-and-desist order to the Teamsters. Tha t ’ snott hef i r s tt i met heI nt e r na t i ona lBr ot he r hoodha sbe e nc a l l e dhonk y .S u c h talk is all over Coachella and Salinas. The Teamster leadership has done little to dispel the r u mor s .Af t e rt hr e ey e a r sof“ or g a ni z i ng ”i nt heS a l i na sf i e l ds ,t heTe a ms t e r sha v ef a i l e dt o deliver union cards to the largely Chicano membership. Without a card, a worker has no rights in the larger union. When Einar Mohn, head of the Western Conference, was questioned about Teamster plans for membership meetings in Coachella, he said it would beac ou pl eofy e a r sbe f or ea nywe r ehe l d .“ I ’ m nots u r e , ”hee x pl a i ne d,“ howe f f e c t i v ea u ni onc a nbewhe ni t ’ sc ompos e dofMe x i c a n-Americans and Mexican nationals with temporary visas. As jobs become more attractive to whites, then we can build a union that c a nne g ot i a t ef r oms t r e ng t h. ” Despite this dubious record, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters continues to claim it bes tr e pr e s e nt st hewor k e r soft heCoa c he l l aVa l l e y . S of a r , t he y ’ v ec ommi t t e dov e r a million dollars to their effort. Agriculture is big business and according to the Teamsters, only an International Brotherhood has the size to handle it. Agriculture is indeed very big business. It accounts for one-third of California jobs and be t t e rt ha nha l foft hes t a t e ’ sa c c u mu l a t e dwe a l t h.I fa l lt hea g r i c u l t u r a lwor k e r sor g a ni z e d i nt oas i ng l eu ni on, i twou l dbet hena t i on’ sl a r g e s ta ndha v ea ni mpor t a nc ebe y ondi t ss ize. Agriculture is rapidly becoming the keystone of the Republicans economy. Faced with ot he ri ndu s t r i e s ’i na bi l i t yt oc ompe t e ,t heUni t e dS t a t e sha smov e di nt oa ni nc r e a s i ng l y unfavorable position in world trade. This has blown the worth out of the dollar and lit a fire under Richard Nixon. He plans to escape the dilemma by increasing the production and export of farm products. Already, government production controls have been lifted and doors opened to the Russian and Chinese markets. Needless to say, Richard Nixon i s n’ tt ooe x c i t e da bou ti nc l u di ngCe s a rCha v e za ndt heUFW i nt ha ts t r a t e g y .He ’ ds l e e pa little easier with it in the hands of his friends. One such friend, Undersecretary of Labor Laurence H. Silberman, arranged for Frank Fitzsimmons to speaka tl a s tDe c e mbe r ’ sa nnu a lc onv e nt i on oft heAme r i c a n Fa r m Bu r e a u .TheFa r m Bu r e a ui sag r owe r s ’or g a ni z a t i onwi t hal onghi s t or yofc a l l i ngu ni ons Commu ni s tf r ont s ,bu tt he yr e c e i v e d Fi t z s i mmons wa r ml y .He c a l l e d Cha v e z“ a r e v ol u t i ona r yf r a u d”a ndg otabig hand. A month later, the Teamsters signed an agreement with the Labor Contractors Association and their representatives showed up in Coachella with an offer. The i rof f e rwa st e nc e nt sa nhou rl e s st ha nt heUFW’ s ,i nc l u de dnohi r i ngha l l ,no special pesticide regulations and was written in English. None of the Teamster rank and file ha v es e e nac opyoft hec ont r a c ty e t , bu tt heg r owe r ss a yi t ’ sa t t r a c t i v e , f a i ra nda bou tt i me . “ I t ’ sni c et oha v es ome bodywi t hal i t t l es t r e ng t honou rs i def oronc e , ”c ommented one Coachella ranch manager. He smiled as he said the words and switched the sides of his mouth. The Teamster strength in Coachella is hard to miss. Most teamsters average better than sixfoot high and 200-pounds heavy. Some are red-necked truckers from Indio; the wa r e hou s e me nf r om L. A. l ookl i k ehi ppi e s , a ndt her e s e tg r e a s et he i rha i ri nt oadu c k ’ sa s s . The ya l lg e tpa i d$ 6 7 . 5 0d a i l yf r om t heu ni on’ sor g a ni z i ngf u nds .Ea c hda ya t5AM,t he s e “ or g a ni z e r s ”a s s e mbl yi nt heS a f e wa ypa r k i ngl otof fHi g hway 111. The fat ones like to stamp their feet on the asphalt and say one Teamster is worth five Mexicans. Those are just about the odds they work. It makes for long hard days. The r ea r ef i v et i me sa sma nyMe x i c a ns ,bu tt he y ’ r emos t l ys ma l la ndha l fa r ewomen and children. They start at 4:30, drinking sugared coffee in the Coachella park across from the hiring hall. As the picket captains pass the word on which ranches are working, the United Farmworkers huddle into caravans, head out the highway and across county roads. The streets running east and west are all named after numbers, the ones north and south after Presidents. The armies rarely get lost. They usually show up about the same time. S i nc eAl i c i aUr i be ’ sde nt e df a c e ,t hec ou r t sha v eg i v e nt heUFW the far side of the road and the Teamsters the side with grapes on it. The judge said the distance would keep things peaceful; Riverside County sheriffs cruise between the lines to make sure. But even the c opsha v e n’ tbe e na bl et ok e e pt henoi s edown. Both sides have full horns and start using them when the first folks show up to work. TheUFW c a l l st he m“ s c a bs . ”Tot heTe a ms t e r st he ya r e“ br ot he rTe a ms t e r s ”a nd“ g ood Me x i c a ns . ”Theol dFor dsa ndne wChe v i e st ha tc omei nt hemor ni ngbr i ngami l dbr e e d. The s epe opl edon’ tt a l kal ot .Whe nt he ydo,t he y ’ r e“ l ook i ngf orwor k . ”Af t e rt he yf i ndi t , t her oa rdoe s n’ ts t a r tdr oppi ngu nt i l t hr e e . The United Farmworkers wave their flags and shout, “ Hu e l g a ! ”into the fields. They stand in a solid line, on tops of cars and in roadside weeds. Most have no idea that James Buchanan was the 15th President of the United States. They know him only as a street in the Coachella Valley. The Teamsters on the other side of the bumpy tar are spread thinner. They like to take their shirts off, flash their tattoos, and every now and then one threatens to drop his pants at the UFW. That always gets a big laugh. One slow morning, the boss Teamster stalked out into the fields, brought 12 workers out, arranged them by an American flag and took their picture for the Teamster newsletter. When they got bored once, some Long Beach banana loaders stuffed a gunny sack, hung it as Cesar Chavez in effigy, and danced around it, spitting and calling the ex-potato bag 14 kinds of motherfucker. At three, the field work stops, the United Farmworkers split for the shade trees in Coachella, and the Teamsters find an air conditioner. No one in the Valley with any sense works past three. Both sides agree to let the sun carry the action until six. Then the battle s t a r t sa l lov e ra g a i n.TheUFW u s e st hec ool e re v e ni ng st os pr e a dou ti nt ot heVa l l e y ’ s sprinkling of little towns and labor camps. On April 24th, 20 strikers from the Coachella-Imperial Distributors Ranch took their leaflets and walked into the CID labor camp. The rest of the 90-strong UFW pickets stayed ont her oa d,byt hel i neofg na r l e dc y pr e s sa ndt hewa v eofs a ndpu s hi ngu pont hec a mp’ s g a t e .The“ c a mp”i sahou s et r a i l e r ,al a r g es i ng l e -roomed building with a bathroom in one end, and two cottages divided into two rooms apiece. The little houses are for families and the big one holds 30 single men. The trailer is pulled by a semi and belongs to the camp manager, a short man with knobs of curly hair on his nose. On April 24th, he never even came outside. As soon as he saw the strikers, he just grabbed the phone. In ten minutes, the police arrived. While the sergeant and the picket captains discussed t heUFW’ sr i g htt obet he r e ,t heTe a ms t e r sbu s t e di n.Mi nu t e sl a t e ra l lhe l lbu s t e dl oos e . The2 0Te a ms t e r swe r el e dbyAlDr ou bi ea ndr us he du pf r om t her oa d.Dr ou bi eha s n’ t been very active in the last month, but in the first two weeks of the strike, he kept busy enough to draw three different assault charges. Droubie paused momentarily at the sight of t hepol i c e .Bu thewa spi s s e dof fa ndbe g a ns c r e a mi ng“ Ge tt hef u c kou tofhe r e , ”he y e l l e d, “ g e tt he s ea s s hol e sou tofhe r e . ” Taking his cue, the pear-shaped Teamster in back of Droubie threw a board into the circle of strikers and began to swing his bicycle chain. It whipped around his head in third gear. Droubie spotted Tom Dalzell, one of the UFW lawyers in the front of the crowd. “ Ge thi m, ”hea l l e g e dl ymu t t e r e da ndt hes q u a tg u yne x tt oDr ou bi ek noc k e dDa l z e l lou t cold with a right hand lead. Droubie himself allegedly chased down UFW organizer Ma r s ha l l Ga nza ndpl owe dhi mi nt ot hes a nd, s c r e a mi ng , “ Fu c ky ou , Ga nz . ”TheTe a ms t e r had ripe sweat streaming down his face and blinked his eyes to keep track of the Teamster charge. The 20-man rush forced the UFW across the sand to the road. Once past the gate, they held their ground by the parked cars and sang, NoTe n e mo sMi e d o . ”Tha tme a ns“ wea r enot a f r a i d”i nMe x i c a n.TheTe a ms t e r ss t oppe da tt hee dg eoft hec a mpa ndpu nc t u a t e dt he song with flyingr oc k st ha tc a r r i e dwi t hawhi s t l ea ndat hu di nt ot hef a r mwor k e r s ’ c a r s . “ Fu c ky ou , ”Dr ou bi es hou t e df r omt hec y pr e s s . The most popular UFW response to the Teamster muscle has been the picket line. As a group, the International brotherhood of Teamsters, Chauffeurs, Warehousemen and Helpers has been shortened to los gorillas. Some mornings, the pickets bring bananas tied to the ends of poles and dangle them at the Teamster line. The Teamsters have been carrying thick sticks, getting tans and picking up Spanish. When they do, the shouting has been k nownt ohu r tt he i rf e e l i ng s .“ Ine v e rc a l l e dt he i rmot he rnoneoft he m na me s , ”t heone c a l l e d“ Ki ngKong ”s a i d. “ I ta i n’ tf a i r . ” Yous e e ,t he s eCha v i s t a sa r ehy poc r i t e s , ”Ra yGr i e g o,Te a ms t e rLoc a l2 0 8 ,e x pl a i ns. Ray came out from L.A. after the first week of the strike. He likes to wear a flat black hat so he looks like Black Bart and loves to talk on the bull horn. Griego is the only Teamster pa t r ol l i ngKa r a ha di a na ndS on’ sRa nc hwhos pe a k sS pa ni s h,s oheg e t sto be the Teamster v oi c ee v e r yda y .“ S ome t i me swhe nI ’ m ou the r e ,Is e et he m pr a yont he i rpi c k e tl i nebu t only 25% of them mean it. One of the guys was flipping me the bird while he was s u ppos e dt obepr a y i ng , Ia s ky ou , i st ha tr e a l ? ” “ We ’ r ej u s the r et opr ot e c tt he s epe opl ei nt hef i e l ds , ”i st hewa yRa yGr i e g os e e shi s j ob.Gr i e g oc l a i mshe ’ sne v e rl a i daha ndona ny bodys i nc ehec a meou tf r om hi shomei n LaMi r a da .“ The s epe opl e , ”hes a y s ,poi nt i ngba c kov e rhi sha tt ot hes t oope ds hou l de r s sin the fi e l d,“ wa ntt owor k .The yg otd a u g ht e r sa nds onsa thome ,bu tt he y ’ r ea f r a i dt o br i ngt he mt ot hef i e l dsbe c a u s eoft he s eCha v i s t a s . S i nc ewe ’ v ebe e nhe r e , t he ybr i ngt he i r kids. “ Doy ouk now, ”Gr i e g oa r g u e s ,“ t he s eCha v i s t a se a tnot hi ngbu tt or t i l l a s ,be ans and pot a t oe sa l lt het i me ?Tha t ’ sa l lt he ye a t ,s we a rt oGod.Ye s t e r da y ,oneoft he mg a v emea burrito. It was pure beans. It got me so mad that this man Chavez comes out here and feeds these people that shit morning, noon and night. So what I did was buy some burritos myself. I came back and gave them a Teamster burrito. It was all meat. I ask you, what kinda union is it that makes its people eat beans? Those people inside the fields are eating be e fi nt he i rbu r r i t os . The y ’ l lt e l ly out he yha v et og owith the people who put meat on the t a bl ea ndt ha t ’ su s . ” Pio Yerpes is a Filipino worker in the fields Ray Griego guards. Like most of the 15 wor k e r sonhi sc r e w,he ’ sbe e nou tofwor kmu c hofhi sl i f e .Fa r ml a bori ss e a s ona l ,bu t living is year-round, which means bills that only a paycheck can satisfy. In April and early Ma y ,t hec r e wdowha t ’ sc a l l e dt hi nni ng .Thebot t om oft heg r a pebu nc hi sc u ta wa yf r om the stem and six branches are left on top to make big, sweet Thompsons. If the job is done wrong, the grapes grow into water berries, bloated and tasteless. In June, the crews are tripled and they begin to pick. If the picking is done too slowly or too late, the grapes shrivel into raisins and droop on the vines, crusting into heaps. Whenever he works, Pio Yerpes uses his bandana to tie a straw hat to his head. Shade collects into a black apron under its brim and falls all over his eyes. “ Ia m ame mbe roft heTe a ms t e r s , ”hes a y s . “ Is i g ne da l r e a dy . I ts e e mst omei t ’ sg ood bu tId on’ tk now mu c ha bou tt hem yet. My boss, Mr. Karahadian, he sign with the Teamsters. Where shall I go? Shall I follow Chavez to strike? Without some money? And whowi l lpa yme ?I ’ ms u ppos e dt of ol l owmybos s .Am Ir i g ht ?Iha v et os u ppor ta l lk i nds of things. Some of my car and everything like this and that. I go with them and what will ha ppe n?The ywi l l g i v eme$ 5 . Ca nIl i v eon$ 5 ?I ts e e mst omet ha t ’ sr i di c u l ou s . ” K. Karahadian, the boss of Pio Yerpes and owner of the fields Ray Griego guards, agrees. Karahadian made his stash in knit sportswear and moved out of L.A. in the Thirties t oowns omeg r a pe s .“ Thi sCha v e zma det oog odda mnma nymi s t a k e s , ”Ka r a ha di a n c l a i ms .“ Wet r i e dt one g ot i a t ewi t ht hi sf e l l owc l e a rba c ki nNov e mbe r .Heha dac ont r a c t that was impossible to live with. About 20 negotiable items and we never got past the fist one. In the meantime, we warned them. The Teamsters are in the Valley, we said, but he wou l dn’ tl i s t e n. ” The 1965 strike hurt Karahadian and thoughts of the new one jam his jaws together; so an oc c a s i ona lwor dbe a c he sononeofhi smol a r sa ndr a t t l e si ns i dehi she a d.“ he...he s i mpl ypu s he dt hewor k e r sa wa yf r om hi su ni on.Wedi dn’ tha v enot hi ngt odowi t hi t .I f Teamsters came into our fields before negotiations, we chased them off. We kept out of the picture completely. We did the best we knew how to get along with this Chavez. Even then, his union was always har . . . harassing us with all kinds of stupid grievances, filling e v e r yda y , j u s ta bs ol u t e l yabu nc hofnot hi ng s . ” As far as Karahadi a ni sc onc e r ne d,t heUFW i sCe s a rCha v e za ndCe s a rCha v e zi s n’ t mu c h.“ He ’ sj u s tnotal a borl e a de r , ”Ka r a ha di a ns a y s .“ He ’ sar e v ol u t i oni s t ,ors ome t hi ng l i k et ha t . Thos et wodon’ tg ot og e t he r . TheTe a ms t e r sa r ei na ndt ha t ’ sa l l . Tha t ’ st hewhol e goddamnt hi ngi nanu t s he l l . ” Ros a r i oPe l a y ou s e dt owor ki nKa r a ha di a n’ sf i e l dsbe f or eRa yGr i e g obe g a nt og u a r d t he m.S het e l l sadi f f e r e ntk i ndofs t or y .“ TheTe a ms t e r sne v e rc a mei nt ot hef i e l dst ot a l k t ou s , ”s hee x pl a i ns .“ Ou rf or e ma nwa saTe a ms t e ra ndhe signed us all up without telling us. The day before the strike, the Teamsters came and broke all our union flags. We had flags on our cars and on the grape rows and they tore them all down. We went to the foreman. We told him that we were still under contract and that we did not permit him to come and molest us. The owner came up and said if we wanted to we could leave. “ Thene x tda y , ”Ros a r i or e c a l l s ,“ t heu ni onpi c k e t sc a mea ndc a l l e du st oc omeou tof the fields. We began to talk to the other workers. When we did, the son of the foreman pi c k e du pag r a pes t a k ea ndt ol dmet ol e a v e . Is a i dIwa sg oi ngt ol e a v ebu tt ha twe ’ da l l g o t og e t he r . Wedi dn’ ta g r e ewi t ht heu ni onhewa nt e d. ” Rosario Pelayo claims she left the fields with 85 others. Her face is expressionless; she doe s n’ tr e a l l ys mi l eorf r own.S hes a y st hec r e wt ha tr e pl a c e dt he mi sf r om Te x a sa nd nor t he r nMe x i c o.“ Thef i r s tt i me rIe v e rg ott ot a l kt oaTe a ms t e r , ”s hec ont i nu e s ,“ wa s ou the r eont hepi c k e tl i ne .It ol dhi mt ha tIdi dn’ tt hi nktheir union was bad but it was very apart from our union. If they wanted to be our union, they should have talked to us. The yd on’ tr e pr e s e ntf a r mwor k e r s . ” Ros a r i oPe l a y o,he rhu s ba nda nds i xc hi l dr e nl i v eon$ 5 0awe e ks t r i k ebe ne f i t s .“ I t ’ s di f f i c u l t , ”s hea dmi t s , : ” bu tweha v et os t r u g g l e . I t ’ sou rl i f e . ” Since April 16th, that life has been a lot more dangerous than they ever expected. The Teamsters started a fear campaign sprinkled with beatings back in April and May. By June the situation became even more tense. June means picking in Coachella and picking is a very touchy time. Grapes must be picked, packed and sent to the cooler at the right moment. Left too long on the vine, the grapes begin to wrinkle and each wrinkle means mone you tofag r owe r ’ spocket. June was slow this year and there were many wrinkles. Crews were short, the strike grew, and the crop began to burn around the edges. The UFW pickets numbered in the hundreds and the Teamsters had to recruit 15-year-olds to do the work. The situation worsened and the Teamsters finally decided to cut the crap and get down to business. June 23rd, 1973, was the Battle of the Asparagus Patch. The attack took shape at seven in the morning around the vineyard owned by Henry Moreno. A hundred United Farmworker pickets got tired of standing next to Avenue 60 and decided to move into a clump of desert between the grapes and a field of asparagus, 90 yards further on. The court injunctions said they had to stay 60 feet from the vines, so the pickets walked the long way and set up behind the field with the asparagus to their backs. Most of the pickets were teenagers, women and children. While they were making their way around the vineyard, 75 Teamsters crunched up behind the vines to watch. The Teamsters split into two groups, one facing the pickets, the other to their side and behind them. The I nt e r na t i ona l Br ot he r hooddi s t r i bu t e dpi pe sa ndt i r ei r ons . I twa s n’ tl ongbe f or et he ybe g a n to take swings and throw rocks at the stragglers in the UFW line. The Teamster leader was known as the Yellow-Gloved Kid. The name came from the squash-colored gloves he never took off. He perched on the back of a white pickup, tugged at his wrists and delivered hoarse shouts. Two fat Teamsters near him carried pistols under their belts. The Teamsters were soaking up the heat like sponges, getting redder ass they waited, and rubbing their hands in wet circles. Then the waiting was over. The Yellow-Gloved Kid lobbed a firecracker towards the UFW pi c k e t .“ Ki l lt he m, ”hea l l e g e dl ys hou t e d.“ Ki l lt he m. ”Tha ts e tt heTe a ms t e r si n mot i ona ndt he i rJ u neof f e ns i v ewa su nde rwa y .Thr e es he r i f f ’ ss t oodbe t we e nt het wo u ni onsbu tt ha tdi dn’ te v e nde ntt heBr ot he r hood’ sr us h.Theg r ou pt ot hes i dea ndba c k drew blood first. The ground they charged across was full of bumps. As the pickets tried to e s c a pe ,t he ys t u mbl e da ndf e l li nt ot heTe a ms t e r s ’pa t h.A ma nna me dTa ma y ohi tt he hardpan deck and two long-haired Teamsters allegedly split his head open with a pipe. It was as easy as swatting flies. For good measure, they spent five minutes kneading him with their size 12s. When Fredrico Sayre tried to help, he was knocked into the sand by a third Teamster coming up from behind. Al lt heUni t e dFa r mwor k e r sbe g a nt or u n,bu tt he r ewa s n’ tr e a l l ya nyplace to run to. The Teamsters had circled them on three sides. Some ran out the open side into the asparagus patch only to be chased down. Before the police reinforcements arrived, several pickets got to sample Teamster benefits close up. A blond Teamster chased Roy Trevino with a tree limb and allegedly beat him to his knees. Each time Trevino staggered to his feet, the Teamster laced him with his piece of tree. When Joe Pavia finally helped him a wa y ,Roy ’ she a dwa sr a i ni ngj u i c ea ndhek e ptc ou g hi ngbl ood in a thin dribble between his lips. Consuelo Lopez found her son Ricardo by a pile of grape lugs with his face pushed i n.Thepol i c ehe l pe dt hehu ndr e dl i mpba c kt ot hema i nr oa d,bu tt he Te a ms t e r sdi d n’ t wa ntt os t op. Onec a l l e d“ Ca tMa n”c ha s e da1 4 -year-old boy down the street and allegedly whipped him with a stick. Another, ran across the road, opened a pickup door, pulled the driver out and kicked his ass with a club. When the dust settled, five UFW members were in the hospital; twenty more were treated and released. Before the June offensive ended four days later, 18 Teamsters faced assault charges; a UFW me mbe r ’ shou s eha dbe e nbu r ne dt ot heg r ou nd; Ce s a rCha v e zwa ss hota t ; a ndf ou r mor eUFW me mbe r swe r ehos pi t a l i z e da f t e rbe i ng“ or g a ni z e d”wi t htire irons. When a priest had his nose broken by a 300-pound Teamster in the middle of a crowded coffee shop, the shit finally hit the fan in the Teamster from office. Frank Fitzsimmons sent his own fact-finders to Coachella and their report clinched it. Mu r r a yWe s t g a t ewa soneoft heme nFi t z s i mmonss e ntt ohe l p“ ma i nt a i ng ood r e l a t i onswi t ht hepr e s s ”a ndr e por tba c k . Ona r r i v a l , Fi t z s i mmons ’e mi s s a r ywa sq u ot e da s s a y i ngt he r emi g htbea“ v i ol e nc e ”pr obl e mi nCoa c he l l a .We s t g a t ewa sha v i ngdi nne ra t the El Morocco Motel in Indio when he got the chance to investigate the problem in greater depth. Teamster Hank Salazar was with him. A Teamster Westgate had never seen before approached Salazar and Westgate looked up from his blue cheese dressing to introduc ehi ms e l f . TheTe a ms t e rba c k e da wa yf r omWe s t g a t e ’ sha nds ha k e . “ Idon’ twa ntt ok nowy ou ,y ous on-of-a-bi t c h, ”t heTe a ms t e rs a i d.“ Whyt hehe l ldoI wa ntt os ha k ey ou rha nd?Yout hi nky ouc a npu l lt ha ts hi tone v e r y one ?Idon’ tl i k ey ou . Ge tf u c k e d. ”Wi t h that, the Teamster walked around the table, allegedly punched Westgate in the mouth and then punched him once again to make sure he remembered the first one. “ Don’ tt r yt opu l l t ha ts hi ta g a i n, ”hes a i da ndl e f t . We s t g a t eont hef l oor . Westgate picked himself up off the carpet and the waitress brought his steak. Ralph Cot ne r ,t heTe a ms t e rAr e as u pe r v i s ora ppr oa c he dhi mf r om a c r os st her oom.“ We s t g a t e , ” hes a i d,“ t he r ea r ef ou rmor eg u y ss t a ndi ngov e rt he r ewhoa r ema dde rt ha nhe l la ty ou , who are waiting t odot hes a met hi ngu nl e s sy oug e tt hehe l lou tofhe r er i g hta wa y . ” We s t g a t ek e pte a t i ng .Asf a ra shec ou l dt e l l ,e v e r y onewa sa ng r ya bou twha the ’ dt ol dt he pr e s s . TheTe a ms t e r swa nt e dnopu bl i c i t yont he“ v i ol e nc epr obl e m. ” Cotner bent over Westgate’ ss hou l de ra g a i n.“ I fy oudon’ twa ntt ha tt hi ngs hov e d downy ou rt hr oa t ”hea l l e g e dl ys a i d,“ y ou ’ dbe t t e rg e tt hehe l lou tofhe r e . ”We s t g a t e l ook e du pa ndS a l a z a ri nt e r c e de d. “ Look , Mu r r a y , ”S a l a z a rs a i d, “ y oube t t e rg e tt hehe l l ou t of here before you ge tk i l l e d. ”We s t g a t ea ba ndone dhi ss t e a ka ndl e f t . Be f or et hee ndofJ u ne ,ne wor de r sc a met oCoa c he l l a .TheTe a ms t e r“ g u a r ds ”we r e pulled out and sent to Arvin and Lamont in Kern County. Director of the Western Conf e r e nc e ’ sAg r i c u l t u r a lWor k e r sOr g a ni z i ng Committee, Bill Grammi, announced the move to the press. “ We ’ r edoi ngt hi s , ”Gr a mmis a i d,“ be c a u s ewebe l i e v et ha tl oc a ll a we nf or c e me nt agencies have realized the need for increasing their forces to the point where their pr ot e c t i ona ppe a r sa de q u a t e . ” But the war continues. The bulk of table grape growers have signed with the Teamsters, and the UFW is still fighting for its life. Coachella is burrowed in front of its coolers now, waiting for November. The harvest is over. The UFW has gone north to Arvin, Delano a ndS e l ma , s t r i k i nga l lt heg r a pe st ha ta r el e f tt os t r i k e . I t ’ saha r df i g htf ort heUFW t owi n by itself. They are a union of poor people—a union that has struck in table grapes, wine grapes, lettuce and vegetables for eight years running. To wink the strikers must make their q u a r t e r sdot hewor kofa$ 5bi l l . I t ’ snote a s ybu tt he i rf r i e nds ’ he l pma yma k ei t . Friends are one commodity the UFW has been able to count on. In the first five-year strike, it was the American grocery shopper who finally brought the growers to the table. When the demand for union grapes forced everything else off the fruit shelves, the UFW g otac ont r a c t . Thene wboy c ot tha sa l r e a dyma det hi sy e a r ’ sg r a pe swor t h$ 2 . 5 0l e s si ft he y don’ tha v et hebl a c ke a g l e , t heUFW s e a l , ont hebox . Fi e l dpr odu c t i oni s3 8 % ofl a s ty e a r ’ s crop and if the price dips much further, growers will be losing money with each box they ship. The biggest farmworker friend has been the AFL-CIO. Three weeks after the strike started, George Meany announced that the 13.5 million member labor federation would tax its members 4¢ a head for three months and give the UFW a strike fund. The money has kept the UFW eating. In the meantime, a lot of grapes have turned brown with puckers all over them like a small prune. Thes ha meofi ta l li st ha tt hemone y ’ swa s t e d.Al lt hemone y —the UFW strike fund, t heTe a ms t e r s ’ mi l l i on, t he$ 2 5 0 , 0 0 0s pe ntbyt heRi v e r s i deCou nt yS he r i f f ’ sDe pa r t me nt — could have been saved with the price of one honest vote. An election would sort out all the c l a i msq u i c k l y ,bu ti t ’ snotl i k e l yt oha ppe ns oon.TheTe a ms t e r sa r e n’ tbi gone l e c t i ons . They have run against the UFW three times in the course of their agricultural organizing a dv e nt u r e sa ndl os te a c ht i me .TheBr ot he r hood’ sa t t i t u des u i t st heg r owe r sf i ne .I t ’ st he case of Keene Lersen that has most of the owners scared. Lersen is one of two Coachella growers who renewed their UFW contracts. In the first strike, he was a grower spokesman. Lersen went around the country telling whoeverwou l dl i s t e nt ha thi swor k e r sdi dn’ twa nta union. Finally, the UFW called the question. Being an honest man, Lersen accepted. A binding vote was arranged by impartial parties and Lersen lost 78 to 2. The nearest thing to an election this time around happened before the strike began. Ms g r .Ge or g eHi g g e ns ,ac ons u l t a ntt ot heUSBi s hops ’Commi t t e eonFa r m La bor ,t ook 25 church and civic leaders into 31 fields and polled the workers. Their poll totaled UFW 795, Teamsters 80, no-u ni on7 8 .I fy ou ’ r eaTe a ms t er or a grower, that adds up to a good reason not to vote. Even without ballots, the Coachella Valley grape workers found ways of making their feelings known. One incident in the first week of the strike has become a farmworkers legend. It began with a young woman member of the UFW and a bull horn. She was with the picket line outside the Bobara Ranch, standing on top of a car. Behind her the sun hung like a yolk lobbed against a blue clapboard wall. “ Re me mbe r , ”s hes hou t e dt ot hewor k e r si nt hef i e l d.“ when we were under contract and we used to have 15-mi nu t er e s tpe r i odse v e r yf ou rhou r s ?Iha v e n’ ts e e na ny one r e s t i ng . Ar e n’ tt he r er e s tpe r i odsa ny mor e ? ” As she finished, the people in the vines began to break into bunches, sit down and light cigarettes. When their break was over, the young woman started in again. “ Re me mbe r ,t oo, ”s hec ont i nu e d,“ howou rc ont r a c tl e tu sl e a v et hef i e l dst og ot ot he ba t hr oom a ny t i mewewa nt e d?Iha v e n’ ts e e na ny onel e a v ef ort heba t hr oom i nt wohou r s . Don’ tt heTe a ms t e r sl e ty ou ? ” Scattered workers began to walk to the portable toilets on the edge of the vineyard. When they returned, the bull horn opened up again. “ Re me mbe r , ”t hey ou ngwoma ns a i d,“ whe nwewe r ea l li nt heu ni ona ndweu s e dt o shout, ‘ Vi v aCh a v e z ’ ? Is there anyone in the fields who still shouts “ Vi v aCh a v e z ! ” The Teamsters forewoman stood up over the vines. “ Ab a j o ,Ch a v e z ”she shouted. Tha t ’ s“ Downwi t hCha v e z . ” As soon as she finished, heads popped up and backs straightened all over the field. “ Vi v aCha v e z , ”t he yy e l l e d. “ Vi v aCha v e z ! ” The Teamsters along the road ran back into the vines, stumbling along the rows and t r i ppi ngont hec r u mbl i ngf u r r ows . “ S hu tu p, ”i swha tt he yt ol dt hewor k e r s . “ Tha t ’ sar i v a l u ni on. ”Wi t ht ha t ,e v e r y onee x c e ptt hef or e woman walked out of the ranch and joined the UFW picket. The young woman got down from the car. “ Si ,s ep u e d e s , ”s hes a i d.( “ Wec a n doi t . ” ) Thes u ns a i dnot hi nga ndonl ydr i ppe da l ongt hey ou ngwoma n’ sba c k ,l e a v i ngt r a c k s on her shirt and toasting the dirt under her feet. On the other side of the avenue, the Teamster forewoman hunkered in the ounce of shade next to the vines, kicking at the heat with her new shoes.