Decision-Making Process in Combat Operations

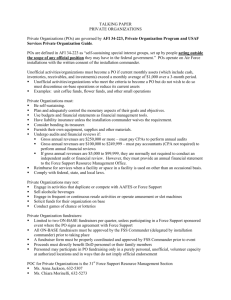

advertisement