1

Ecology and Romanticism

Special Subject, Semester 1, 2010-11

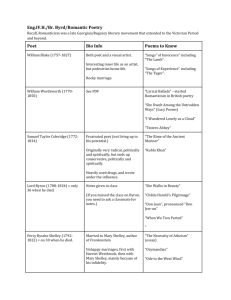

2

Special Subjects I, U67080 Ecology & Romanticism

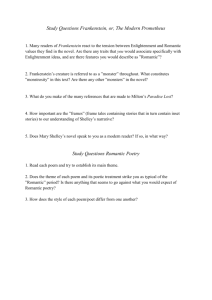

Time & Place: Tuesdays, 1‐4pm, Gibbs G5.37 Ecology & Romanticism Seminar Leader: Simon Kövesi Email: skovesi@brookes.ac.uk Office: Tonge, T4.08 Tel.: 01865 483587 Office Hours: Monday, 10‐11am; Wednesday, 10‐11am At the end The Song of the Earth, Jonathan Bate asserts that ‘poetry is the place where we save the earth’. Can this be true? Can literature, more broadly, play a concrete role in our relationship with the natural world? Is the literary past of any relevance to the environmental issues we face today? This course aims to interrogate this set of problems, along with many others proffered by the loose school of current ‘ecocriticism’. It approaches writers of the Romantic period (c. 1780‐1832) through the theories, practices and ethics of contemporary ecological criticism, and it focuses in particular on the ways one Romantic writer – John Clare – is being ‘used’ by contemporary environmentally‐conscious writers for differing ends. This is therefore a course which is engaged with a particular part of literary history, but one which is theoretically based in current ecological concerns. The course will focus explicitly upon a range of ecologically‐grounded theoretical, critical and political positions, including: deep ecology; eco‐anarchism; apocalypticism; ecofeminism; environmentalism; millenarianism; social (or Marxist) ecology; ecofascism. It will consider how ‘nature’ is constructed in literature, and to what ends. This special subject focuses upon poetry and prose by William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Mary Shelley, Percy Shelley, George Gordon Byron and John Clare; the novel The Last Man by Mary Shelley, and the play Prometheus Unbound by Percy Shelley. It also considers contemporary prose works by Adam Foulds, Iain Sinclair and Richard Mabey. The weekly reading of ecological criticism will be a central part of the work for this module, and students must expect to read all of Greg Garrard’s Ecocriticism (which is listed as a primary text below), and to read supplementary critical and theoretical materials supplied by the tutor. Students will be required to present in class twice: firstly an analysis of a Romantic‐period text, and secondly on their own critical ‘discovery’ in the final week. Texts by Smith, Blake, William Wordsworth, Coleridge, Byron, Keats and Percy Shelley are available in the Duncan Wu anthology (listed below). Other texts you will be reading are listed below, or are provided in an ‘Appendix of Texts’ in week 1. 3

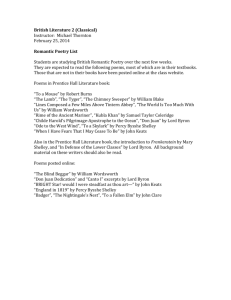

Primary Reading List

(students are expected to have copies of all primary texts and to bring them to class) Clare, John, Major Works, Eric Robinson (ed.) (Oxford World’s Classics, 2008). Foulds, Adam, The Quickening Maze (Jonathan Cape, 2009). Garrard, Greg, Ecocriticism (Routledge, 2004). Mabey, Richard, Nature Cure (Vintage, 2008). Shelley, Mary, The Last Man (Oxford World’s Classics, 1998). Sinclair, Iain, Edge of the Orison: In the Traces of John Clare’s ‘Journey Out of Essex’ (Penguin, 2006). Wu, Duncan, (ed.), Romanticism: An Anthology. Third Edition. (Blackwell, 2005). Cheap (sometimes very cheap!) copies of all of these books can be bought via websites such as abebooks.co.uk, amazon.co.uk, bookdepository.co.uk, acadreamia.co.uk and so on. It is worth having a look around, for sure. 4

Reading & Seminar Schedule

Unless otherwise indicated, page references are to Romanticism, 3rd Edition, ed. Duncan Wu. HO indicates that the text is provided in the Hand Out ‘Appendix of Texts’. Week Ecocritical Reading Romantic Literature Reading Week 1 Raymond Williams, definition of ‘nature’ from Keywords (1983) (HO) Charlotte Smith: ‘Sonnet IV To the Moon’, 86; ‘Sonnet XII Written on the Seashore’, 89. William Blake: ‘The Book of Thel’, 176; ‘The Sick Rose’, 196; ‘A Poison Tree’, 202. William Wordsworth: ‘The Rainbow’, 528; ‘Resolution and Independence’, 529; ‘Daffodils (‘I wandered lonely as a cloud’); 546, ‘The Solitary Reaper’, 548. Pre‐Romantic Samples of Nature Poetry: Anne Finch, ‘A Nocturnal Reverie’ (1713) (HO) John Gay, ‘The Shepherd and the Philosopher’ (1728) (HO) Thomas Gray, ‘Elegy Written in a Country Church Yard’ (1751) (HO) William Wordsworth, ‘Tintern Abbey’, 407; ‘Nutting’, 475; ‘Ode. Initiations of Immortality...’, 538. William Blake, ‘The Shepherd’, ‘The Echoing Green’, ‘The Lamb’, 180; ‘The Sick Rose’, ‘The Fly’, 196; ‘The Tyger’, 197; ‘My Pretty Rose‐

Tree’, ‘Ah, Sunflower!’, 198; ‘The Garden of Love’, 199. William Wordsworth, ‘Michael: A Pastoral Poem’, 510 John Keats, ‘To Autumn’, 1419 Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ‘Chamouny: the Hour Before Sunrise’, 677; Percy Shelley: ‘To Wordsworth’, 1052; ‘Mont Blanc’, 1075; John Clare, ‘I am’, 1237; ‘An Invite to Eternity’, 1238 John Keats, ‘When I have fears...’, 1351; ‘Bright star...’, 1433 Mary Shelley, The Last Man Byron, ‘Darkness’ (on handout) (HO) Tues, 28 Sep Week 2 5 Oct Week 3 12 Oct Week 4 19 Oct Week 5 26 Oct Garrard, ‘Beginnings’, 1‐15 Jonathan Bate, ‘Introduction’ to Romantic Ecology (HO) Garrard, ‘Positions’, 16‐32 and ‘Pastoral’, 33‐58. Terry Gifford, ‘Three Kinds of Pastoral’ (HO) Garrard, ‘Wilderness’, 59‐

84. Karl Kroeber, ‘Introducing Ecological Criticism’ (HO) Garrard, ‘Apocalypse’, 85‐

107. Morton Paley, ‘The Last Man: Apocalypse Without Millennium’ (HO) 5

Week 6 Week 7 9 Nov Week 8 16 Nov Week 9 23 Nov Week 10 30 Nov Week 11 7 Dec Week 12 Reading Week No Seminar Submit 2,000‐word essay by 1pm on Friday 5 November. Garrard, ‘Dwelling’, 108‐

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ‘Kubla Khan’, ???; 135. ‘Frost at Midnight’, 625 Dorothy Wordsworth, ‘A Cottage in Grasmere Vale’, 588 Leigh Hunt, ‘To Hampstead’, 795 John Clare, ‘The Flitting’, 1230 Percy Shelley, ‘Epipsychidion’ (HO) Garrard, ‘Animals’, 136‐159. Robert Burns, ‘To a Mouse’, Wu, 268 Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ‘The Nightingale; A James McKusick, ‘Ecology’, Conversational Poem’, 353 Percy Shelley, ‘To a Skylark’, 1181 from Romanticism: An John Keats, ‘Ode to a Nightingale’, 1395 Oxford Guide (HO) John Clare, ‘The Nightingale’s Nest’, Major Works, 213 Garrard, ‘Futures’, 160‐182. Richard Mabey, Nature Cure John Clare, Major Works, xvii‐xxxii; 1‐96. Bob Heyes, ‘John Clare and Enclosure’ (HO) Timothy Morton, ‘John Iain Sinclair, Edge of the Orison Clare’s Dark Ecology’ (HO) John Clare, Major Works, 96‐249; 429‐483. Dale Jamieson, ‘Nature’s future’, from Ethics and the Environment (HO) Writing Week Adam Foulds, The Quickening Maze John Clare, Major Works, 250‐354. No Seminar Submit 4,000‐word essay by 1pm, Friday, 17 December. 6

Tasks

Reading: every week Read the poetry, plays and novel on the reading list as indicated week‐by‐week above in continuous conjunction with the critical reading from Greg Garrard’s Ecocriticism, and together with the other suggested critical reading. These reading tasks you should of course carry out before attending that week’s seminar. The reading will prepare you to engage fully in class discussion about them, every seminar, every week. You might not understand everything you read: that’s what seminars are for! So, bring questions, problems, your own ‘eureka’ moments (or their opposite), and hopefully we can work through them in seminar, and so all reach better, fuller, and more sophisticated comprehension of the texts and the issues they raise through dialogue. Critical and ecological research: every week As one half of the title of this module suggests, we are here to engage with and understand ecology – and the best way for you to do that is to build up a portfolio of materials – articles, essays, commentaries, websites, news items and so on – that help you develop and challenge your comprehension of contemporary debates about ecology, environmental issues, literary writing about nature, and ecocriticism. Seminars: every Tuesday Courses like this one only work if you engage 100% ‐ and that means attend every session, and turn up on time and well prepared, ready to talk, ask questions and provide your fellow seminar‐goers responses to their questions and problems. Ideally, the tutor is just a facilitator of student discussion, who sets up and chairs debate and oral critique. Seminars will however include lecture‐style monologue from the tutor, as well as active in‐class analysis of Romantic and critical texts. As usual, seminar attendance is monitored, all absences recorded and forwarded to the module leader and third‐year tutor. Seminar Presentations: once this semester In session 1 you will be asked to sign up to do a presentation on one of the texts. This is not assessed but is mandatory for all students. The presentation can highlight any aspect of a text, approach or context you choose, and is intended to be a stimulant for class discussion. The presentation should be somehow tied to one of the 7

Romantic‐period texts we are studying that week. The presentation does not have to last longer than 5 minutes, should not take much time to prepare and should be informal, based on notes (i.e. not a scripted reading) and should set up some questions and issues for the class to consider. The tutor will help you if you’re at all worried, but you shouldn’t be. It is a chance for you to lead the run of play for a while, have fun and be critically creative and playful, and take risks. If you wish, you can team up to do joint presentations. You can also use presentations to develop, test and discuss ideas you are considering for your essays. Essays: week 6 and week 12 Your two assessed essays must address separate topics and include references to different texts (i.e. you must not do two essays on the same text or the same topic), though you can make some brief references to the same texts. As this is a double‐

credit third‐year module, you are required to use critical, historical and/or theoretical work for both your essays. You are encouraged to range way beyond the set and recommended texts in your frame of reference, though set texts must be substantially referred to in both essays. The longer essay should discuss two or more primary texts. First essay: 2,000 words, submit during week 7 seminar or by 1pm to blue drop box, on Friday 5 November. 30% of total marks. Second essay: 4,000 words, submit by 1pm, Friday 17 December (end of week 12). 70 % of total marks. Essay submission Essays should be typed with double spaces between lines. Essays must be accompanied by an attached signed and dated standard ‘English Studies Essay Cover and Mark Sheet’, and should be placed in Simon Kövesi’s blue drop box on the ground floor of Tonge before the deadline as indicated above. Please fasten your essay and cover sheet together securely as pages can go missing. Any essays not following these basic formatting and presentational requirements will be returned unmarked. The essays must follow the regulations as set out in the English Stage 2 handbook – and will be marked according to the criteria set out therein. The usual University penalties for late submission apply. For guidance and for help on writing essays, and for late submission regulations, please consult your English Studies Student Handbook. For further guidance on citation in your essays, visit the library research guides online at: http://www.brookes.ac.uk/services/library/guideintro.html#research. 8

Essay Titles A list of suggested titles from which to draw, for both essays, appears below. You can also write your own essay questions, for both essays, but you must consult with the seminar tutor before you start writing up the essay. This requirement is for your benefit, so please take the time to talk through the essay title, and a full essay plan, with your tutor, a long time before the deadline. Essay questions should be answered with reference to critical and Romantic‐period texts you have read for this course. 1. ‘It is critically invalid to write about the world of physical nature, and the world of text, at the same time, with the same authority, or with the same approach: Romantic poets, their contexts, and indeed Romantic visions of nature, only exist to us as texts. As Derrida said, “there is nothing outside the text”.’ Consider this quotation in light of the reading you have done for this course. 2. Discuss how and why the Romantic poets thought poetry could change the world. 3. ‘Environmental criticism in literature and the arts clearly does not yet have the standing within the academy of such other issue‐driven discourses as those of race, gender, sexuality, class, and globalisation.’ (Lawrence Buell, The Future of Environmental Criticism, 129). Consider the extent to which ‘environmental criticism’ should or should not have the same ‘standing’ as other ‘issue‐driven’ critical approaches. 4. ‘The bright sun was extinguish'd, and the stars / Did wander darkling in the eternal space, / Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth / Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air…’ (Byron, ‘Darkness’). Why and in what ways do the Romantics imagine and explore death of humanity, and of the natural world? 5. ‘All sighed when lawless law's enclosure came’ (John Clare, ‘The Mores’). Was John Clare right to be so angry about enclosure? 6. ‘Thou hast a voice, great Mountain, to repeal / Large codes of fraud and woe…’ (Percy Shelley, ‘Mont Blanc’). Why did the Romantic poets believe so strongly in the liberating power of the natural world? 7. The perspective of William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge ‘may legitimately be termed an ecological view of the natural world, since their poetry consistently expresses a deep and abiding interest in the Earth as a dwelling‐

place for all living things.’ (James C. McKusick, Green Writing: Romanticism and Ecology, 29). Do you agree with McKusick’s characterisation of Wordsworth and Coleridge, and can the same ‘ecological view’ be found in other writers of the Romantic period? 9

8. Explore the relationship between Romantic subjectivity and the natural world in texts you have read for this course. 9. ‘Ecocritics, to do something genuinely meaningful… must offer readers a broader, deeper, and perhaps more explicit explanation of how and what environmental literature communicates than the writers do themselves, immersed as they are in their own specific narratives. Crucial to this ecocritical process of pulling things (ideas, texts, authors) together and putting them in perspective is our awareness of who and where we are.’ (Scott Slovic, Going Away to Think: Engagement, Retreat and Ecocritical Responsibility, 34). Discuss with reference to texts and contexts you have encountered on this course. 10. ‘Prophets proclaiming imminent catastrophe are nothing new in the history of Western culture... The approach of inevitable doom has become the conventional wisdom of the late twentieth century.’ (Ronald Bailey, Eco‐Scam: The False Prophets of Ecological Apocalypse, 2). How significant is ‘apocalypticism’ a factor in the environmental discourse of Romanticism, and how might it relate to the environmental discourse of the twenty‐first century? 11. Is the response of the Romantics to nature always gendered? 12. Following other critics, Greg Garrard (Ecocriticism, 1–15) suggests that we should always be aware of the rhetorical devices which environmental writers deploy to get us thinking in certain ways about nature and about our relationship to it. Consider the implications of the rhetorical strategies of two or more Romantic‐

period writers in their ‘construction’ of nature. 13. Deep ecology ‘identifies the dualistic separation of humans from nature... as the origin of environmental crisis’ (Greg Garrard, Ecocriticism, 21). Do Romantic writers follow this same distinction between man and nature, or do they close the gap? 14. Consider the ways in which contemporary creative artists have responded to John Clare’s legacy, and explore the possible intentions they might have in deciding using, and re‐writing, Clare. You may refer to any novelists, prose writers, poets, artists, and musicians you find. 15. ‘John Clare is a poet of loss of the natural world, and this is the central reason Mabey, Sinclair, Foulds and others are fascinated by him: contemporary society has itself lost all connection with a natural world which it has ruined irredeemably. Society’s only recourse is nostalgic sentimentality.’ Discuss. 16. ‘A separation between man and nature is not simply the product of modern industry or urbanism; it is a characteristic of many earlier kinds of organized labour, including rural labour.’ (Raymond Williams, ‘Ideas of Nature’, [1972], Culture and Materialism, [Verso, 2005], 82). Discuss with reference to both Romantic texts and contemporary texts. 10

Library Resources

It is a requirement of this module that you show engagement with critical, historical and theoretical research on the authors and the wider Romantic period, and on ecological theories and current environmental debates. The Brookes library stocks paper copies of and provides electronic access to journals such as Romanticism, Studies in Romanticism, the John Clare Society Journal, Essays in Criticism, ELH, Gothic Studies, Nineteenth‐Century Contexts, Nineteenth‐Century Fiction, Nineteenth‐Century Literature, Studies in English Literature and Years Work in English Studies. Two Romantic‐period online journals provide fully scholarly, peer‐reviewed editions and articles: Romantic Circles and Romanticism on the Net (details under ‘websites’ below). • Research Tip (1): MLA Bibliography To find specific articles, you should make use of the online MLA Bibliography. To get to it, go to the Electronic Library at: www.brookes.ac.uk/services/library/eleclib.html ...then click on ‘Databases’, then ‘M’, then on ‘MLA international bibliography’. Not all the articles listed will be available at OBU, but many will, and some are accessible online via the OBU Library site. Ask me, or a librarian, for help. • Research Tip (2): JSTOR Another excellent database of articles to which the library subscribes is JSTOR. Again, on the Brookes library website, go to ‘Databases’, click on ‘J’ and scroll down to JSTOR. If you use the ‘Advanced Search’ option, then take the tick out of the box ‘Search for links to articles outside of JSTOR’, and then put a tick in the box below next to ‘Type’ which says ‘Article’, the results returned to you on your search will contain only links to articles which are stored by JSTOR and which you can open, save and/or print out as PDFs. If you are not already using the OED online to find out what words meant in the Romantic period, you will find it also via the Electronic section of the OBU library website (‘Database’ or ‘Reference’ sections). This is a vital tool for the study of language use in our period. Use the library’s subject‐based guide to get straight to the heart of the many resources on offer, here: www.brookes.ac.uk/library/english.html 11

Reading Lists

These broken down below into sections for ease of use – but not exhaustive – success on this course is dependent upon your own extensive research and critical discoveries. This is not a comprehensive list of possible secondary sources: it is just a start! A fine place to start and a solid introduction to the topic of this whole course (which includes some model ecological readings of Romantic texts), and which is included in your ‘Appendix of Texts’, is: McKusick, James C., ‘Ecology’, Romanticism: An Oxford Guide, ed. Nicholas Roe (Oxford University Press, 2005), 199‐218. Ecology, Ecocriticism & Romanticism Baker, Brian, Iain Sinclair (Contemporary British Novelists) (Manchester University Press, 2007). Barrell, John, The Idea of Landscape and the Sense of Place, 1730‐1840: an Approach to the Poetry of John Clare (Cambridge University Press, 1972). Bate, Jonathan, John Clare: A Biography (Picador, 2003). ——Romantic Ecology: Wordsworth and the Environmental Tradition (Routledge, 1991). ——The Song of the Earth (Picador, 2000). Beer, John (ed.), Questioning Romanticism (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995). Biehl, Janet, Finding Our Way: Rethinking Ecofeminist Politics (Black Rose Books, 1991). Brewer, Richard, The Science of Ecology, 2nd edition (Saunders College, 1994). Brownlow, Timothy, John Clare and Picturesque Landscape (Clarendon Press, 1983). Buell, Lawrence, The Future of Environmental Criticism: Environmental Crisis and Literary Imagination (Blackwell Publishing, 2005). Butler, Marilyn, Romantics, Rebels and Reactionaries (Oxford University Press, 1981). Chandler, James, England in 1819: the Politics of Literary Culture (University of Chicago Press, 1998). Clare, John, The Natural History Prose Writings of John Clare, ed. Margaret Grainger (Oxford University Press, 1984). Coupe, Laurence, ed., The Green Studies Reader: from Romanticism to Ecocriticism (Routledge, 2000). Crawford, Rachel, Poetry, Enclosure, and the Vernacular Landscape, 1700‐1830 (Cambridge University Press, 2002). Curran, Stuart (ed.), Cambridge Companion to Romanticism (Cambridge University Press, 1993). Fill, Alvin, and Peter Mühlhäusler, eds, The Ecolinguistics Reader: Language, Ecology and Environment (Continuum, 2001). Fisch, Audrey, (ed.) et al. The Other Mary Shelley: Beyond Frankenstein (Oxford University Press, 2003). 12

Foot, Paul, Red Shelley (Sidgwick and Jackson and Michael Dempsey, 1980). Foster, John Bellamy, Ecology Against Capitalism (Monthly Review Press, 2002). ——The Vulnerable Planet: a Short Economic History of the Environment (Monthly Review Press, 1999). Foulds, Adam, The Quickening Maze (Jonathan Cape, 2009). Garrard, Greg, Ecocriticism (Routledge, 2004). Gill, Stephen, The Cambridge Companion to Wordsworth (Cambridge University Press, 2003). Gilroy, Amanda (ed.), Green and Pleasant Land: English Culture and the Romantic Countryside (Peeters, 2004). Goodridge, John and Simon Kövesi, (eds.), John Clare: New Approaches (John Clare Society, 2000). Guattari, Félix, The Three Ecologies, trans. Ian Pindar and Paul Sutton (Continuum, 2000). Hanley, Keith and Raman Selden (eds), Revolution and English Romanticism (Harvester Wheatsheaf, 1990). Haughton, Hugh (ed.), [et al], John Clare in Context (Cambridge University Press, 1994). Holmes, Richard, Shelley: the Pursuit, second edition (Flamingo, 1995). Jamieson, Dale, Ethics and the Environment: an Introduction (Cambridge University Press, 2008). Jarvis, Robin, The Romantic Period: the Intellectual and Cultural Context of English Literature, 1789‐1830 (Pearson‐Longman, 2004). Kerridge, Richard and Neil Sammells, eds, Writing the Environment: Ecocriticism and Literature, (Zed, 1998). Kroeber, Karl, Ecological Literary Criticism: Romantic Imagining and the Biology of the Mind (Columbia University Press, 1994). Lacey, Norman, Wordsworth’s View of Nature, and its Ethical Consequences (Archon Books, 1965). Lederer, Susan E., Frankenstein: Penetrating the Secrets of Nature (Rutgers University Press, 2002). Love, Glen A., Practical Ecocriticism: Literature, Biology and the Environment (University of Virginia Press, 2003). Lovejoy, Arthur O., The Great Chain of Being: a Study of the History of an Idea (Harper and Row, 1960). Lovelock, James, Gaia: a New Look at Life on Earth (Oxford University Press, 1979). Mabey, Richard, In a Green Shade: Essays on Landscape, 1970‐1983 (Hutchinson, 1983). ——The Unofficial Countryside (Collins, 1973). ——Weeds (Profile Books, 2010). McCalman, Iain [et al] (eds), An Oxford Companion to the Romantic Age: British Culture 1776–1832 (Oxford University Press, 2001). McKusick, James, Green Writing: Romanticism and Ecology (Macmillan, 2000). Morton, Timothy (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Shelley (Cambridge University Press, 2006). ——Ecology Without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics (Harvard University Press, 2007). O'Flinn, Paul, How to Study Romantic Poetry, second edition (Macmillan, 2001). Preminger, Alex and T. V. F. Brogan [et al] (eds), The New Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (Princeton University Press, 1993). 13

Rigby, Kate, Topographies of the Sacred: The Poetics of Place in European Romanticism (University of Virginia Press, 2004). Roe, Nicholas (ed.), Romanticism: An Oxford Guide (Oxford University Press, 2005). Rossendale, Steven, ed., The Greening of Literary Scholarship: Literature, Theory, and the Environment (University of Iowa Press, 2002). Sheppard, Robert, Iain Sinclair (Writers & Their Work) (Northcote House, 2007). Sinclair, Iain, London Orbital: a Walk Around the M25 (Penguin, 2003). Slovic, Scott, Going Away to Think: Engagement, Retreat, and Ecocritical Responsibility (University of Nevada Press, 2008). Stabler, Jane, Burke to Byron, Barbauld to Baillie, 1790‐1830 (Palgrave, 2002). Storey, Mark, The Problem of Poetry in the Romantic Period (Macmillan, 2000). Thompson, E. P., Customs in Common (Penguin, 1993) —— The Making of the English Working Class (Penguin, 1991) —— The Romantics: England in a Revolutionary Age (Merlin, 1997) Williams, Raymond, Keywords: A vocabulary of culture and society (Fontana, 1983). Worster, Donald, Nature’s Economy: a History of Ecological Ideas (Cambridge University Press, 1985). Wu, Duncan, ed., A Companion to Romanticism, (Blackwell, 1998). Mary Shelley, The Last Man: Canuel, Mark, ‘Acts, Rules, and The Last Man’, Nineteenth‐Century Literature, 53:2 (September 1998), 147‐70. URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2902981 Fisch, Audrey, (ed.) et al. The Other Mary Shelley: Beyond Frankenstein (Oxford University Press, 2003) [Contains various essays on Last Man]. Lederer, Susan E., Frankenstein: Penetrating the Secrets of Nature (Rutgers University Press, 2002). Mellor, Anne, Mary Shelley: her Life, her Fiction, her Monsters (Routledge, 1988). Sussman, Charlotte, ‘“Islanded in the World”: Cultural Memory and Human Mobility in The Last Man’, PMLA, 118:2 (March 2003), 286‐301. URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1261415 Sterrenburg, Lee, ‘The Last Man: Anatomy of Failed Revolutions’, Nineteenth‐Century Fiction, 33:3 (December 1978), 324‐47. URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2933018 Wagner‐Lawlor, Jennifer, ‘Performing History, Performing Humanity in Mary Shelley’s The Last Man’, Studies in English Literature, 1500‐1900, 42:4, ‘Nineteenth Century’ (Autumn 2002), 753‐80. URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1556295 Williams, John, Mary Shelley: a Literary Life (Macmillan, 2000). Percy Shelley Allott, Miriam (ed.), Essays on Shelley (Liverpool University Press, 1982). Blank, Kim (ed.), The New Shelley: Later Twentieth‐Century Views (Macmillan, 1991). —— Wordsworth's Influence on Shelley: a Study of Poetic Authority (Macmillan, 1988). 14

Clark, Timothy and Jerrold Hogle, (eds), Evaluating Shelley (Edinburgh University Press for the University of Durham, 1996). Cox, Jeffrey, Poetry and Politics in the Cockney School: Keats, Shelley, Hunt and Their Circle (Cambridge University Press, 1998). Everest, Kelvin (ed.), Shelley Revalued (Barnes and Noble, 1983). —— (ed.), Percy Bysshe Shelley: Bicentenary Essays (D.S. Brewer, 1992). Foot, Paul, Red Shelley (Sidgwick and Jackson and Michael Dempsey, 1980). Gilmour, Ian, The Making of the Poets: Byron and Shelley in Their Time (Chatto and Windus, 2002). Holmes, Richard, Shelley: the Pursuit, second edition (Flamingo, 1995). Holmes, Richard (ed.), Shelley On Love: an Anthology (Anvil Press/Wildwood House, 1980). McCalman, Iain (ed.), An Oxford Companion to the Romantic Age: British Culture 1776–1832 (Oxford University Press, 2001). Morton, Timothy (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Shelley (Cambridge University Press, 2006). O'Neill, Michael, Shelley (Longman, 1993). Scrivener, Michael Henry, Radical Shelley (Princeton University Press, 1982). Tomalin, Claire, Shelley and His World (Thames and Hudson, 1980). Wasserman, Earl, Shelley: a Critical Reading (Johns Hopkins Press, 1971). John Clare (see back issues of the John Clare Society Journal too) Barrell, John, The Idea of Landscape and the Sense of Place, 1730‐1840: an Approach to the Poetry of John Clare (Cambridge University Press, 1972). Bate, Jonathan, John Clare: A Biography (Picador, 2003). Brownlow, Timothy, John Clare and Picturesque Landscape (Clarendon Press, 1983). Chirico, Paul, John Clare and the Imagination of the Reader (Palgrave Macmillan, 2007). Clare, Johanne, John Clare and the Bounds of Circumstance (McGill‐Queen's University Press, 1987). Clare, John, Champion of the Poor: Political Poetry and Prose (MidNAG/Carcanet, 2000). ——The Letters of John Clare, Mark Storey (ed.), (Clarendon, 1985). ——The Living Year 1841, Tim Chilcott (ed.), (Trent Editions, 1999). ——The Prose of John Clare, J.W. and Anne Tibble (eds), (Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1970). ——The Shepherd's Calendar, Eric Robinson and Geoffrey Summerfield (eds), (Oxford University Press, 1964). Deacon, George, John Clare and the Folk Tradition, second edition (Francis Boutle, 2002). Goodridge, John, (ed.), The Independent Spirit: John Clare and the Self‐Taught Tradition (John Clare Society and the Margaret Grainger Memorial Trust, 1994). Goodridge, John and Simon Kövesi, (eds.), John Clare: New Approaches (John Clare Society, 2000). 15

Haughton, Hugh (ed.), [et al], John Clare in Context (Cambridge University Press, 1994). Janowitz, Anne, Lyric and Labour in the Romantic Tradition (Cambridge University Press, 1998). Kövesi, Simon, ‘John Clare’s "I" and "eye": Egotism and Ecologism’ in Green and Pleasant Land: English Culture and the Romantic Countryside, ed. Amanda Gilroy (Leuven, 2004), 73–88. Leader, Zachary, Revision and Romantic Authorship (Clarendon Press, 1996). Lucas, John, England and Englishness: Ideas of Nationhood in English Poetry 1688‐

1900 (Hogarth, 1990). John Clare (Northcote House, 1994). Martin, Philip, ‘Authorial Identity and the Critical Act: John Clare and Lord Byron’, in Questioning Romanticism, ed. by John Beer (Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995). McKusick, James, Green Writing: Romanticism and Ecology (Macmillan, 2000). Sales, Roger, John Clare: A Literary Life (Palgrave, 2002). Storey, Mark, Clare: the Critical Heritage (Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1973). Vardy, Alan, John Clare, Politics and Poetry (Palgrave, 2003). Selected Creative Works responding to John Clare (other than the ones on primary reading list: all of these are in short loan) •

Fine Art: Akroyd, Carry, natures powers & spells: Landscape Change, John Clare and Me (Langford Press, 2009). Shields, Brian, ‘Inside Outside (Clare with Claire)’, http://brianshields‐artist.co.uk/ [See top‐right image on front of this handbook]. •

Novels: Allnatt, Judith, The Poet’s Wife (Doubleday, 2010). Moore, Alan, Voice of the Fire (Top Shelf Productions, 2009). •

Plays: Bond, Edward, The Fool, in Plays, Three: Bingo / The Fool / The Woman / Stone (Methuen Drama, 1987). Rae, Simon, Grass (Top Edge Press, 2003). •

Poetry: Lucas, John, ed., For John Clare: An Anthology of Verse (John Clare Society, 1997) Also see back issues of the John Clare Society Journal, which contains a wide variety of poetry, prose and art. Full stock in OBU library. 16

Websites N.B.: There is of course a massive amount of Romantic‐related material on the Internet, and probably even more about ecology and environmental issues such as global warming. Please be very discerning when online materials, and ensure you follow the guidelines produced by the library for correct referencing of Internet sources in written work, online at: http://www.brookes.ac.uk/services/library/citeweb.html A general rule of thumb for use of the internet for your research is: if in any doubt at all as to quality and veracity of what you find, go to a book instead. Be very cautious if you cannot find an author’s name or a date of publication on an internet source. Academic books, essays and articles go through a rigorous process of peer refereeing and reviewing by experts; most website resources, including the delightful mess that is Wikipedia, do not. Two Romantic exceptions are the highly reliable, scholarly sites, Romantic Circles and Romanticism on the Net, listed below. Good places to start, on current debates about the environment: Guardian Unlimited, ‘Environment’ http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment The Times Online, ‘Environment’ http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/environment/ The Telegraph, ‘Earth’ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/earth/index.jhtml New Statesman, ‘Green Thinking’ by Mark Lynas http://www.newstatesman.com/columns/green‐thinking Association for the Study of Literature and Environment http://www.asle.org/ World Wildlife Fund http://www.wwf.org.uk/core/index.asp Greenpeace http://www.greenpeace.org.uk/ 17

Romantic Sites: Byron Chronology: http://www.rc.umd.edu/reference/byronchronology/index.html Byron (some useful info. especially on Caroline Lamb and Anne Isabella Milbanke): http://www.englishhistory.net/byron.html Byron (good textual resource): http://www.cas.astate.edu/engphil/gallery/byron.html PB Shelley Chronology by Carl Stahmer: http://www.rc.umd.edu/cstahmer/shelcron/ John Clare Page: http://www.johnclare.info/ Romantic Circles: http://www.rc.umd.edu/ Romantic Period Chronology: http://english.ucsb.edu:591/rchrono/ Romanticism on the Net: http://www.ron.umontreal.ca/ Voice of the Shuttle: Romanticism (links): http://vos.ucsb.edu/browse.asp?id=2750 18

Official Documentation 1. MODULE NUMBER AND TITLE: U67082 SPECIAL SUBJECT 3: OPTION: ECOLOGY AND ROMANTICISM 2. Module Leader: Caroline Jackson‐Houlston Unit Leader: Simon Kövesi 3. Course Description This advanced Honours module and the other Special Subjects modules offer a basket of courses in English from which students can select, in order to pursue their particular areas of historical interest or thematic specialisms. The options offered are based on the current research interests of staff and may therefore vary from year to year, but the department sustains historical and generic coverage in line with the Core courses. Individual options differ in the exercises set but all equate to 6,000 words of coursework. All options share the aim of introducing students to areas of staff research specialism so that they can engage directly with current research and evaluate it in relation to a specialised body of primary texts and to the contexts of original production and subsequent re‐production of those texts. Students will be expected to take proactive control of their own learning through fulfilling a range of assessment possibilities unique to each option. At the end The Song of the Earth, Jonathan Bate suggests that ‘poetry is the place where we save the earth’. Can this be true? This option aims to interrogate this claim, along with many others proffered by the loose school of current ‘ecocriticism’. It approaches writers of the Romantic period (c. 1780‐1832), and contemporary writers responding to Romanticism, through the theories, practices and ethics of contemporary ecological criticism. It is therefore a module which is engaged with a particular part of literary history, the Romantic period, but one which is theoretically based in current ecological concerns. 4. Relationship with other Modules Pre‐requisites: Co‐requisites: Level and Status: 2 credits from: U67020, U67021, U67022, U67023, U67024, U67025, U67029 none . Level 6 Honours Component double module. Alternative compulsory for BA English (XE), BA English Studies (EX) Acceptable for English (EA), English Studies (EN) Semester 2 Placement: 5. Content The course will focus explicitly upon a range of ecologically‐grounded theoretical, critical and political positions, including: deep ecology; eco‐anarchism; apocalypticism; ecofeminism; environmentalism; millenarianism; social (or Marxist) 19

ecology; ecofascism. In light of these politicised critical positions, the course approaches and evaluates Romantic‐period texts in extended seminar discussion, such as poetry of Charlotte Smith, William Wordsworth, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, George Gordon Byron, John Keats, Percy Shelley and John Clare; the journal of Dorothy Wordsworth; the novel Frankenstein by Mary Shelley, and Percy Shelley’s play Prometheus Unbound. 6. Learning Outcomes 6.1 Knowledge and Understanding Taught

Practised Assessed

Having completed this module successfully, students will have developed their abilities to: 9

9 9 i. Display knowledge and understanding of a range of representative Romantic writing 9 9 9 ii. Display knowledge and understanding of the social, political and historical contexts of these writings iii. Display knowledge and understanding of recent 9 9 9 and current ecocritical investigation into the concepts and issues of a wide variety of responses to ‘nature’ and ‘environment’ iv. Consider, compare and contrast the ways in which the Romantic writers wrote about the 9 9 9 natural world and man’s position in relation to it 6.2 Professional Skills Having completed this module successfully, students will Taught Practised Assessed

have developed their abilities to: 9 9 9

i. Deploy close reading skills in a variety of texts 9 9 9 ii. Contextualise texts theoretically, with particular attention to issues of nature and environment 9 9 9 iii. Apply ecocritical theoretical models to those texts and contexts iv. Produce theoretically‐informed, well‐structured, 9 9 9 relevant arguments, supported by appropriate textual evidence 20

6.3 Transferable Skills Having completed this module successfully, students will have developed their abilities to: i. Communicate findings orally and in written form ii. Work productively independently and in groups iii. Listen effectively and learn from discussion iv. Recognise and discriminate between a variety of competing theoretical, social, and aesthetic positions v. Produce written work in line with correct academic protocol vi. Make use of feedback to improve performance vii. Think analytically viii. Carry out independent research using a range of resources, including books, journal articles, and electronic sources ix. Develop and complicate understanding and knowledge of literary history x. Develop an informed understanding of contemporary environmental and ecopolitical discourse 7. Teaching and Learning Experiences Taught

9

9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 Practised Assessed

9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 9 Students completing this module will have been given the opportunity to: • attend 30 hours of seminars (10 x 3‐hour sessions) which incorporate a lecture‐style element, but which are predominantly focused around student text‐based activities and presentation of weekly discoveries and lines of enquiry • research and write about topics and texts within the remit of the module • use e‐learning resources such as articles and online media to enhance seminar preparation and research towards assessment • attend one hour of one‐to‐one tutorial time across the semester to discuss issues raised by the course • receive oral and written feedback on assessed tasks 21

Students completing this module will have: • completed written work •

received feedback on assessed work The module and option will run in Semester 2 of every year, as long as staffing allows. It is currently scheduled for Monday mornings. 8. Notional Learning Time Total: 300 hours for this double Undergraduate module. Seminars 30 hours 1 hour Tutorial 269 Self‐directed study 9. Assessment Coursework 100% The assessment will primarily address Learning Outcomes 6.1, 6.2 and 6.3, in the following ways: • First essay (2,000 words, 30%): 6.1 i‐iv; 6.2 i‐iv; 6.3 i, iv, v, vii‐x • Second essay (4,000 words, 70%): 6.1 i‐iv; 6.2 i‐iv; 6.3 i, iv, v, vii‐x 10. Indicative Reading See above 11. Validation History This module and indicative options were validated February 2003.