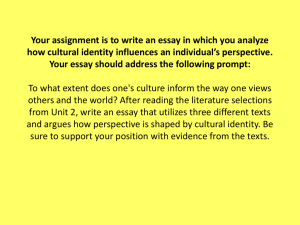

Romantic Literature Essay Titles: Nature & Environment

advertisement

Essay Titles A list of suggested titles from which to draw, for both essays, appears below. You can also write your own essay questions, for both essays, but you must consult with the seminar tutor before you start writing up the essay. This requirement is for your benefit, so please take the time to talk through the essay title, and a full essay plan, with your tutor, a long time before the deadline. Essay questions should be answered with reference to critical and Romantic‐period texts you have read for this course. 1. ‘It is critically invalid to write about the world of physical nature, and the world of text, at the same time, with the same authority, or with the same approach: Romantic poets, their contexts, and indeed Romantic visions of nature, only exist to us as texts. As Derrida said, “there is nothing outside the text”.’ Consider this quotation in light of the reading you have done for this course. 2. Discuss how and why the Romantic poets thought poetry could change the world. 3. ‘Environmental criticism in literature and the arts clearly does not yet have the standing within the academy of such other issue‐driven discourses as those of race, gender, sexuality, class, and globalisation.’ (Lawrence Buell, The Future of Environmental Criticism, 129). Consider the extent to which ‘environmental criticism’ should or should not have the same ‘standing’ as other ‘issue‐driven’ critical approaches. 4. ‘The bright sun was extinguish'd, and the stars / Did wander darkling in the eternal space, / Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth / Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air…’ (Byron, ‘Darkness’). Why and in what ways do the Romantics imagine and explore death of humanity, and of the natural world? 5. ‘All sighed when lawless law's enclosure came’ (John Clare, ‘The Mores’). Was John Clare right to be so angry about enclosure? 6. ‘Thou hast a voice, great Mountain, to repeal / Large codes of fraud and woe…’ (Percy Shelley, ‘Mont Blanc’). Why did the Romantic poets believe so strongly in the liberating power of the natural world? 7. The perspective of William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge ‘may legitimately be termed an ecological view of the natural world, since their poetry consistently expresses a deep and abiding interest in the Earth as a dwellingplace for all living things.’ (James C. McKusick, Green Writing: Romanticism and Ecology, 29). Do you agree with McKusick’s characterisation of Wordsworth and Coleridge, and can the same ‘ecological view’ be found in other writers of the Romantic period? 8. Explore the relationship between Romantic subjectivity and the natural world in texts you have read for this course. 9. ‘Ecocritics, to do something genuinely meaningful… must offer readers a broader, deeper, and perhaps more explicit explanation of how and what environmental literature communicates than the writers do themselves, immersed as they are in their own specific narratives. Crucial to this ecocritical process of pulling things (ideas, texts, authors) together and putting them in perspective is our awareness of who and where we are.’ (Scott Slovic, Going Away to Think: Engagement, Retreat and Ecocritical Responsibility, 34). Discuss with reference to texts and contexts you have encountered on this course. 10. ‘Prophets proclaiming imminent catastrophe are nothing new in the history of Western culture... The approach of inevitable doom has become the conventional wisdom of the late twentieth century.’ (Ronald Bailey, Eco‐Scam: The False Prophets of Ecological Apocalypse, 2). How significant is ‘apocalypticism’ a factor in the environmental discourse of Romanticism, and how might it relate to the environmental discourse of the twenty‐first century? 11. Is the response of the Romantics to nature always gendered? 12. Following other critics, Greg Garrard (Ecocriticism, 1–15) suggests that we should always be aware of the rhetorical devices which environmental writers deploy to get us thinking in certain ways about nature and about our relationship to it. Consider the implications of the rhetorical strategies of two or more Romanticperiod writers in their ‘construction’ of nature. 13. Deep ecology ‘identifies the dualistic separation of humans from nature... as the origin of environmental crisis’ (Greg Garrard, Ecocriticism, 21). Do Romantic writers follow this same distinction between man and nature, or do they close the gap? 14. Consider the ways in which contemporary creative artists have responded to John Clare’s legacy, and explore the possible intentions they might have in deciding using, and re‐writing, Clare. You may refer to any novelists, prose writers, poets, artists, and musicians you find. 15. ‘John Clare is a poet of loss of the natural world, and this is the central reason Mabey, Sinclair, Foulds and others are fascinated by him: contemporary society has itself lost all connection with a natural world which it has ruined irredeemably. Society’s only recourse is nostalgic sentimentality.’ Discuss. 16. ‘A separation between man and nature is not simply the product of modern industry or urbanism; it is a characteristic of many earlier kinds of organized labour, including rural labour.’ (Raymond Williams, ‘Ideas of Nature’, [1972], Culture and Materialism, [Verso, 2005], 82). Discuss with reference to both Romantic texts and contemporary texts.